File

advertisement

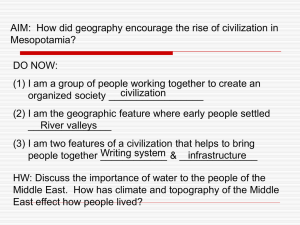

Cooley 1 Sean Cooley Professor Jablonski ANTH 040H 9 February 2016 Development of Agriculture in Southwest Asia Mesopotamia is almost universally recognized in world history as one birthplace of human civilization, marking a drastic change from the living practices of the past. But people rarely question how and why it developed into what it once was. One of the first steps, if not the first step in creating complex civilization was developing an effective agricultural system. Anthropologists have evidence of groups settling in the fertile crescent around 10,000 BCE, but there is also support for the idea that tribes were occupying this territory much early as more of a nomadic people (Mark). These nomadic tribes were able to develop agriculture due to a number of environmental advantages that the fertile-crescent provided, the development of complex harvesting and farming tools, and the intense sharing of ideas and technology between various tribes in the region facilitated through trade. Additionally, it was agricultural positive feedback loops that allowed meager plant domestication to develop into full-scale agricultural production. A key environmental advantage that these Mesopotamian tribes had was the two rivers that helped carve out their home, the Tigris and Euphrates. For many groups these two environmental assets provided an effective place to become sedentary due to easy access to both water and an effective system of irrigation for agriculture in an otherwise dry area. However, “information on irrigated regions is derived from both sites in northern and southern Mesopotamia, with irrigation being far more common in southern Mesopotamia.” (Altaweel Cooley 2 829). Furthermore, “irrigation was likely more limited in use in northern Mesopotamia, and often limited to alluvial zones near major watercourses.” (Altaweel 829) Despite this perceived disadvantage, the northern more mountainous region of Mesopotamia had increased rainfall due to other environmental factors. Nevertheless, this lack of irrigation agriculture did have an effect on how many northern Mesopotamian cities could because agriculture could not be utilized as well as in the south. There was also a, “cultural break between the alluvial south and or north and in effect between and steppe, hilly, east, irrigation rainfall-agriculture zones in Greater.” (Rothman 92). Before nomadic people would ever have conjured the idea behind agriculture and crop harvesting, they would be encouraged and incentivized to settle in Mesopotamia due to the relatively easy access to water, which is essential for sustaining groups of people. In addition to the rivers that provided the necessary source of life for agriculture, there were also a vast number of crops native to the Mesopotamian Mediterranean corridor. These two elements went hand in hand to not only encouraging the development of agriculture but also almost creating it. It is believed that, “environmental constraints at the Last Glacial Maximum and afterwards made all but the Mediterranean woodland corridor, with its grasses, cereals and legumes, unsuitable for the emergence of sedentary hunting and gathering.” (Watkins 147) This suggests that not only was agriculture encouraged in Mesopotamia, it may have been the only place for some distance that could sustain agriculture during the advent of the civilization. This gave Mesopotamia a huge strategic advantage in developing a complex human society. It is widely accepted that, “sedentary hunter-gatherers reliant on wild harvests of cereals and legumes had emerged in the early Natufian, and were then profoundly affected by the reduction in resources… they began to turn to the cultivation of some of those plant species” (Watkins 147- Cooley 3 148). Ancient Mesopotamians did not choose to suddenly switch entirely from a system of hunting and gathering to intense agriculture. Instead, they began by casually planting certain native crop seeds from grasses, cereals, etc., in addition to maintaining their busy hunting and gathering schedule. This casual planting of certain crops created a positive feedback loop that encouraged an increase in the amount of agriculture that an individual took part in, and a decrease in the amount of hunting and gathering. By simply starting a small degree of plant domestication, individuals were increasing their dependence on the land, and thus increasing their tendency towards sedentism. As this domestication increased, it was only natural that their dependence on the land would increase, and furthermore their tendency towards sedentism. Overall, “the farming of cereals and pulses increased the tendency to sedentism (Watkins 145). At Jericho and Tell Aswad, remains of domesticated cereals and pulses were found dating back 10,000 B.P., which confirms this theory (Moore & Hillman 491). Regardless of how suitable the environment was for farming, the early Mesopotamian settlers needed a good source of hunting game as well in order to have a suitable environment. Without a consistent source of meat, they would be unlikely to survive considering that gathering alone was not a lucrative as it came to be with the development of agriculture. Fortunately for these ancient Mesopotamians, there was no substantial deterioration in the pattern of hunting after the Epipaleolithic. In a Northern Mesopotamian region, “the pattern of hunting remained the same throughout the sequence of occupation at Abu Hureyra, indicating that the deterioration in climate had no adverse effect on the density of the herds of Persian gazelle.” (Moore & Hillman 490). Furthermore, there is evidence that after the last glacial maximum the only place suitable for sedentary hunting and gathering was the Mediterranean corridor of Mesopotamia Cooley 4 (Watkins 147-148). With an abundance of wild game and crops available in one location, it would be likely that groups may begin to decide on a more sedentary lifestyle in this resource paradise. “At the beginning of the early Neolithic, there are several sedentary hunter-gatherer sites outside the Levantine corridor, three of which (Qermez Dere, Nemrik and M’lefaat) are in north Iraq. (Watkins 148). Intensification of a sedentary lifestyle in this region could easily lead to the development of agriculture. It would take one person with an idea, or maybe the witnessing of a seed growing into a consumable crop. This is of course assuming its leaders or the group as a whole respect and embrace new ideas in these communities. But the mere fact that these groups were willing to convert to a sedentary style of life suggests that they would be very open to new innovation that could improve their life. Both agriculture and herding developed in about 10,000 BCE, and they both complement each other in a number of key ways, but primarily in their increased sedentary nature (Watkins 163). Although it is unclear which came first, they more than likely developed together as a result of the exchange of ideas between multiple tribes and modification of those ideas. Mesopotamia is birthplace of one of mankind’s crowning inventions. It in turn allowed all of ancient Mesopotamia to spur into one of the first great human civilizations. This invention was the sickle, and it allowed high quantities of crops to be processed at a very rapid rate. It was essentially a blade that cut various cereals and other crops. It did away with the need to harvest crops with only ones hands. Anthropologists have found that, “sickle technology for harvesting cereals and other plants first appears in Southwest Asia during the Early Natufian tradition sometime between 14,500 and 12,800 BP. These tools bear a sheen or gloss caused by silica Cooley 5 accumulation subsequent to cutting silica rich plants.” (Goodale et al. 1192). The model and idea slowly spread to areas all over the world, with different areas making various modifications. By speeding up the time it takes to harvest crops, the sickle made agriculture much more realistic to previously subsistence hunters and gatherers. They could stay completely sedentary yet still process huge amounts of food for themselves or their tribe. Various research has been preformed, analyzing the sustainability and duration of ancient Mesopotamian sickles in order to determine overall utility of one of these tools. Particularly, “Tool life history, or more specifically tool curation, which can be viewed as the ratio of realized to maximum utility of a tool, has been the subject of recent and active debate. These and other authors have developed a series of indices to understand how tools change through use, repair, and sharpening episodes.” (Goodale et al. 1194). It is important to determine the utility of a sickle for these tribes, because the more utility a person could get out of a single sickle, the greater the investment payoff for creating the tool is in the first place. This increases the overall likelihood that a tribe would decide to create more, and thus increases the chances that this tribe engages in agriculture in general. The sickle also facilitated the positive feedback loop that initial crop domestication created. The huge investment that ancient Mesopotamians put into the production of sickles would encourage them to further pursue agriculture as somewhat of a replacement for hunter and gathering. Largely, “our preliminary interpretation of well-made sickles with long use-lives, potentially extending over more than one harvest season, indicates that the tools were an important part of the early Neolithic tool kit. This importance reflects ideas that the emerging way of life and intensified subsistence strategy on cereal grains was not only economic, but involved profound shifts in attitudes to material culture.” (Goodale et al. 1199). Cooley 6 These early Mesopotamian farmers were able to “intensify their subsistence strategy,” which is the first step toward larger forms of farming and even commercial farming. Although modern anthropologists are struggling to find the correct proportion of sickles that would fit the amount that were produced for agriculture in Mesopotamia, there is a possible explanation for why the percent of sickles is so low. “The first potential reason why no early Neolithic tool assemblage is comprised of more than 4.7% sickle blades could be related to the identification of sickle polish on stone tools.” (Goodale et al. 1193). The sickle polish is literally polish that forms on the blade of a sickle and, “note that at times silica polish may be misidentified or is too minimal to be detected. Additionally, some stone raw materials may not naturally display sickle gloss.” (Goodale et al. 1193). Although the sickle allowed ancient farmers to harvest at a far greater rate, they still lacked proper ways with which to process the food that they have harvested. There are a few important tools that largely helped solve this problem and improved the nutrition of the food that they were eventually consuming. These tools were, “a grinding slab (or quern) is a lower, stationary stone used with an upper, mobile handstone. Both are mainly used for grinding. A mortar is a lower, stationary stone used with an upper, mobile stone (usually elongated) called a pestle. Both are mainly used for pounding.” (Wright 240). These tools had their own specific purposes in the processing of the food, but they all had primarily the same purpose, which was to grind the food down. More specifically, “mortars and pestles were used to process cereals, chicory, hasanu-plants, onions, grapes, dates, spices, sesame and nidaba seeds.” (Wright 241). There were a number of key reasons why it was advantageous for harvesters to grind down their crop. “Pounding and grinding serve four functions in processing plant foods: to remove fiber, to Cooley 7 reduce particle sizes, to aid detoxification, and to add or remove nutrients.” (Wright 242), Furthermore, the grinding down of these crops, “plays a key role in lithic reduction,” (Wright 240), and “grinding of bran-rich dehusked grain into "groats" (coarsely milled particles) slows this process and permits more nutrients to be absorbed by the gut.” (Wright 244). The anthropological record indicates that there were rising numbers of grinding tools as time went on in ancient Mesopotamia, which suggests that people were attempting to maximize the total value of their food and would allow larger populations of people to be fed with the same amount of food.” (Wright 257). Grinding tools made agriculture even more attractive to humans seeing that you could even increase the total utility of your food after you have harvested it. This is so remarkable because there had never before been an example of people altering their food in order to increase its nutritional value. “Paradoxically, the very qualities making cereals difficult to process small "packages" and hard, tight husks-are what make them eminently storable. These circumstances perhaps reinforced pressures first triggered by sedentism (and rising populations) in the Early Natufian.” (Wright 257). The native crops in their completely natural form actually encouraged a sedentary lifestyle and made life more favorable for those that chose to adopt it. Gatherers could of course create similar tools and increase the utility of their total crop load but their would not be able to increase nearly as much as those people that began taking up farming because the sheer load of crops that you can collect through gathering is nothing compared to what you get from organized subsistence farming. The investment that Mesopotamians put into the production of grinding tools, and the increased nutritional value of the food would further support the agricultural positive feedback loop. It takes time and effort to create complex grinding tools, and Cooley 8 by recognizing the increase in nutritional value in agriculture, individuals would incline them to focus more on agricultural production. It is believed that those that chose to exploit sickle technology chose to use them often, “blade edges indicate an extensive amount of use that perhaps implies the tools were used on a seasonal or potentially even multi-seasonal basis.” (Goodale et al. 1200). Although modern anthropologists are struggling to find the correct proportion of sickles that would fit the amount that were produced for agriculture in Mesopotamia, there is a possible explanation for why the percent of sickles is so low. “The first potential reason why no early Neolithic tool assemblage is comprised of more than 4.7% sickle blades could be related to the identification of sickle polish on stone tools.” (Goodale et al. 1193). The sickle polish is literally polish that forms on the blade of a sickle and, “note that at times silica polish may be misidentified or is too minimal to be detected. Additionally, “some stone raw materials may not naturally display sickle gloss.” (Goodale et al. 1193). The environment and the set of tools that humans were able to develop in the various tribes of Mesopotamia definitely set the region up for the development of agriculture and much more sedentary lifestyle. However, if it were not for these tribes to share information between each other than many regions may have been unable to replicate the same tools, technology and ideas that other tribes had already developed previously. According to the anthropological community, “there may be a case to be made for understanding the rapid spread of cultivation and herding, and domesticated crops and animals, around much of 'the hilly flanks of the Fertile Crescent' within the context of the transmission of innovations. One of the features of competitive emulation is likely to be degrees of intensification.” (Watkins 155). Regardless of exactly how you view the spread of innovation and idea throughout the question, it was Cooley 9 obviously an essential part of the intensification of lifestyles all over the region, which includes agriculture, which was necessary for the intensification of their lifestyle. It is possible that, “there may be a case to be made for understanding the rapid spread of cultivation and herding, and domesticated crops and animals, around much of 'the hilly flanks of the Fertile Crescent' within the context of the transmission of innovations. One of the features of competitive emulation is likely to be degrees of intensification.” (Watkins 155). Both of these ideas both claim that there was most definitely a sharing of ideas and innovation, but this idea offers a concrete reason for why it would actually happen. The newly quasi-sedentary lives that Mesopotamian tribesmen had created also had a number of consequences. This new type of living sometimes required the hunters to travel long or longer distances in order to find prey. In this way, hunters from different tribes could very easily run into one another while tracking and hunting the same heard of animals. Although it could be very possible that these run-ins would end in a less than peaceful manner, but there is also the chance that these groups embrace each other which would open up the idea to the exchange of technology and ideas. If one of these two tribes had no knowledge of agriculture and the other did, the idea could be easily spread and utilized from one tribe to another. There were a few key elements of exchange that allowed ideas to be spread over the vast landscape, “(a) competition and competitive emulation; (b) symbolic entrainment, and the transmission of innovation; and (c) increased flow in the exchange of goods.” (Watkins 161). Not all of these elements correspond directly to the spread of agricultural practices, but rather shows all of the ways that people were able to exchange during the time period and the different advantages that exchange provided for everyone. Cooley 10 Through the environment that Mesopotamian tribes thrived under, the technology that was developed in the region, and the spread of innovation and ideas between tribes, these tribes were able to establish the first wide spread system of agriculture. However, these elements would have ultimately not been able to facilitate agriculture if it were not for the power of the agricultural positive feedback loops. It opened the entire world to the possibility of complex society and was the basis for sustaining large populations in a single location. The way in which agriculture created the opportunity for and eventual implementation of civilization is complex, but would help in the understanding of the benefits of agriculture in general compared to preagricultural society. Cooley 11 Works Cited Altaweel, Mark. "Investigating Agricultural Sustainability and Strategies in Northern Mesopotamia: Results Produced Using a Socio-ecological Modeling Approach." Investigating Agricultural Sustainability and Strategies in Northern Mesopotamia: Results Produced Using a Socio-ecological Modeling Approach. Journal of Archaeological Science, Apr. 2008. Web. 06 Mar. 2014. Goodale, Nathan, Heather Otis, William Andrefsky, Jr., Ian Kuijt, Bill Finlayson, and Ken Bart. "Sickle Blade Life-history and the Transition to Agriculture: An Early Neolithic Case Study from Southwest Asia." Journal of Archaeological Science, June 2010. Web. 06 Mar. 2014. Mark, Joshua J. "Mesopotamia." Ancient History Encyclopedia. N.p., 2 Sept. 2009. Web. 04 Mar. 2014. Moore, A. M. T., and G. C. Hillman. "The Pleistocene to Holocene Transition and Human Economy in Southwest Asia: The Impact of the Younger Dryas." American Antiquity 57.3 (1992): 482-94. JSTOR. Web. 06 Mar. 2014. Rothman, Mitchell S. "Studying the Development of Complex Society: Mesopotamia in the Late Fifth and Fourth Millennia BC." Journal of Archaeological Research 12.1 (2004): 75119. JSTOR. Web. 06 Mar. 2014. Watkins, Trevor. "Supra-Regional Networks in the Neolithic of Southwest Asia." Journal of World Prehistory 21.2 (2008): 139-71. JSTOR. Web. 06 Mar. 2014. Cooley 12 Wright, Katherine I. "Ground-Stone Tools and Hunter-Gatherer Subsistence in Southwest Asia: Implications for the Transition to Farming." American Antiquity 59.2 (1994): 238-63. JSTOR. Web. 6 Mar. 2014.