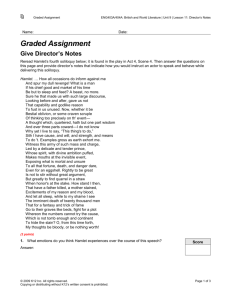

Soliloquy 4.4 Analysis

advertisement

Hamlet Soliloquy 4.4 Introduction One of Shakespeare's most interesting, yet tragically most often forgotten soliloquy's takes place at the end of Act four Scene four of Hamlet. As with any Shakespearean work, the language makes it very difficult for people in today's world to understand. The following breaks down the soliloquy point by point, into giving some insight into the work and explaining it in more modern language. Set Up The soliloquy happens near the end of the play, after Hamlet has journeyed away from home. Here he sees Fortinbras of Norway leading a massive army to fight for a small and meaningless plot of land, worth nothing to either side. The soldiers fight not for wealth, but for honor. This causes Hamlet, a philosopher and scholar, to reflect on his own condition the direction his own path must take. Hamlet's father has been slain by his uncle, who then took the throne and married Hamlet's mother, yet he has done nothing to avenge the honor of his father or redeem the honor of his mother. The Soliloquy How all occasions do inform against me, And spur my dull revenge! What is a man, If his chief good and market of his time Be but to sleep and feed? a beast, no more. Sure, he that made us with such large discourse, Looking before and after, gave us not That capability and god-like reason To fust in us unused. Now, whether it be Bestial oblivion, or some craven scruple Of thinking too precisely on the event, A thought which, quarter'd, hath but one part wisdom And ever three parts coward, I do not know Why yet I live to say 'This thing's to do;' Sith I have cause and will and strength and means To do't. Examples gross as earth exhort me: Witness this army of such mass and charge Led by a delicate and tender prince, Whose spirit with divine ambition puff'd Makes mouths at the invisible event, Exposing what is mortal and unsure To all that fortune, death and danger dare, Even for an egg-shell. Rightly to be great Is not to stir without great argument, But greatly to find quarrel in a straw When honour's at the stake. How stand I then, That have a father kill'd, a mother stain'd, Excitements of my reason and my blood, And let all sleep, while, to my shame, I see The imminent death of twenty thousand men, That, for a fantasy and trick of fame, Go to their graves like beds, fight for a plot Whereon the numbers cannot try the cause, Which is not tomb enough and continent To hide the slain? O, from this time forth, My thoughts be bloody, or be nothing worth! What makes this particular soliloquy so interesting among the rest, is that it presents a very important change for Hamlet, a change from inaction to action, from apathy to passionate pursuit of his goal. Throughout this soliloquy we see Hamlet move through various stages of thought, from philosophical reflection, to inward reflection on the state of his own heart, to reflection on the actions of those around him and what they can teach him, back to philosophical reflection on the nature of greatness, and how he must achieve it and ultimately to from reflection to declaration of his actions from this time forth. In order to fully understand his journey, let us break this soliloquy down point by point. The Break Down How all occasions do inform against me, And spur my dull revenge! Here Hamlet is looking at the world and how everything around him points out how wrong his actions are. To inform against, literally means to accuse (Dolven). It is as if the world itself and all situations he finds are accusing him of apathy and reminding him of the his inability to complete his revenge. What is a man, If his chief good and market of his time Be but to sleep and feed? a beast, no more. This is a more direct and self explanatory line than one often finds in Shakespeare, while at the same time bearing with it a powerful depth. Hamlet is saying that a man who exist but to eat and sleep is no more than a mere animal. Man is a being made to think, to reason, to laugh, to love, to create art, and to seek higher goals and more meaningful pursuits than simply survival. This point reminds me of another passage by one of the 20th Century's greatest thinkers, C. S. Lewis. In his essay Learning in War-Time Lewis writes "Human Culture has always had to exist on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself... The insects have chosen a different line; they have sought first the material welfare and security of the hive, and presumably they have their reward. Men are different. They propound mathematical theorems in beleaguered cities, conduct metaphysical arguments in condemned cells, make jokes on scaffolds, discuss the last new poem while advancing to the walls of Quebec, and come their hair at Thermopylae. This is not panache; it is our nature." (Lewis) Sure, he that made us with such large discourse, Looking before and after, gave us not That capability and god-like reason To fust in us unused. This is a very interesting point. Hamlet is saying that God did not give humanity the ability to think, to look to the past and future and reflect on what has been and what could be, just for us to waste it. To fust literally means to decay. Hamlet praises human knowledge and reason, calling it "god-like", and warns that if unused it will eventually die and rot away. Now, whether it be Bestial oblivion, or some craven scruple Of thinking too precisely on the event, A thought which, quarter'd, hath but one part wisdom And ever three parts coward, I do not know Why yet I live to say 'This thing's to do;' Sith I have cause and will and strength and means To do't. There is quite a lot in this sentence. Hamlet's main point is that he does not know how he can live knowing what he should do, and having all means strength, and desire to do so, yet still having the deed remain undone. He begins by saying that it may be animal-like forgetfulness or a fear coming from over-thinking the situation and to carefully considering the consequences, a type of reasoning which would only be one quarter reason and three quarters cowardice. Examples gross as earth exhort me: Witness this army of such mass and charge Led by a delicate and tender prince, Whose spirit withdivine ambition puff'd Makes mouths at the invisible event, Exposing what is mortal and unsure To all that fortune, death and danger dare, Even for an egg-shell. Here Hamlet looks out at the army before him and see's how they go to war, risking their lives for a a worthless "eggshell" of a patch of ground. He see's the prince, young and inexperienced ("delicate and tender"), standing off and laughing in scorn (making mouths at) at the unforeseen outcome (invisible event) of the battle, and sending his men off to ultimate danger, and even death. Rightly to be great Is not to stir without great argument, But greatly to find quarrel in a straw When honour's at the stake. In this section, Hamlet reflects on the nature of greatness. There are two compelling interpretations of his thoughts on greatness. The first is that greatness means to refuse to stand back and wait and wait for an excuse to act, but to find a compelling reason out of trifling matters, when honor is at stake (Dolven). The other is that greatness does not mean to wildly, and violently stand against any slight offense, but to find a true reason to defend one's honor that which may simply appear to be trifling matters. How stand I then, That have a father kill'd, a mother stain'd, Excitements of my reason and my blood, And let all sleep, while, to my shame, I see The imminent death of twenty thousand men, That, for a fantasy and trick of fame, Go to their graves like beds, fight for a plot Whereon the numbers cannot try the cause, Which is not tomb enough and continent To hide the slain? Quite a bit is said in this massive sentence. Here marks the central move in Hamlet's turning point. This is the crescendo of this soliloquy, where it reaches it's most intense and passionate. Hamlet has contemplated the brave actions of the soldiers as they march off to imminent doom for the shear sake of honor of king and country, yet Hamlet has not taken arms against the massive affront to the personal honor of himself, his father, his mother, and the state of Denmark itself. His father was murdered, his mother stained with incest, by marrying her husbands brother. These sick action provoke his sense of reason and his passions (excite his reason and blood) to just revenge. He laments the fact that to his shame twenty thousand men go to their doom as easily as the would go to bed, all for an illusion (a fantasy and trick of fame). They fight for a small piece of land not even large enough to hold the graves of all who will die there; yet he, who would be fighting for something real, has don nothing, despite the fact that he has the means and strength and desire to do it. O, from this time forth, my thoughts be bloody, or be nothing worth! With this, Hamlet vows to think of nothing else but his bloody revenge against his uncle. From this moment forth he promises to stand for nothing else than that which he long knew he must do, and Hamlet makes good on his vow. The rest of Hamlet's actions throughout the play focus on executing his revenge, which eventually culminates on one of the most tragic and heartbreaking scenes in the whole of English Literature. Conclusion This speech in William Shakespeare's Hamlet is one of sweeping emotion, captivating language, intriguing thought and a spectacular character, driven through and enormous arc all within one single glorious speech. It is an oft' forgotten gem within the enormous sea of brilliant Shakespearian works, and one that is certainly worth diving into that sea to discover. Dolven, Jeff, ed. Hamlet. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 2007. 283-84. Print. Klein, Patricia S., ed. A Year With C.S. Lewis: Daily Readings from His Classic Works. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2003. 271. Print.