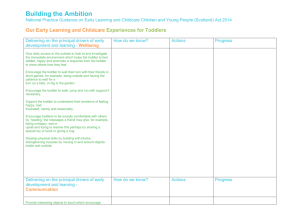

Every Toddler Talking Phase One - Department of Education and

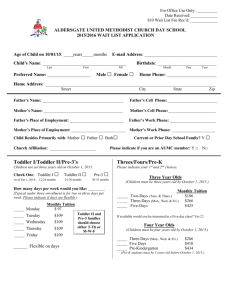

advertisement