Wlf 314 Dr. Rachlow 10 September 2010 Assignment One

advertisement

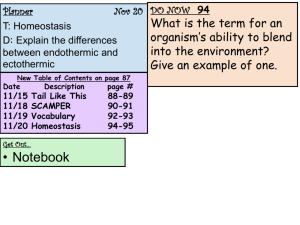

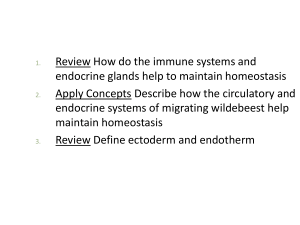

Wlf 314 Dr. Rachlow 10 September 2010 Assignment One: Evolution of Endothermy Were crocodilians once endothermic? In the November/December 2004 issue of Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, Roger Seymour, of the University of Adelaide argued against John Ruben, of Oregon State University, and Wilhelm Hillenius, of the College of Charleston, South Carolina, that crocodilians are actually descended from endotherms and that they later re-evolved back to being ectotherms (Watanabe 2005). In the paper by Myrna Watanabe, titled, “Generating Heat: New Twists in the Evolution of Endothermy”, the argument is discussed about whether or not crocodilians are indeed descendents of endotherms or if their ancestors have always been ectotherms. The problem is that the ancestors that first possessed endothermy are now extinct, and only speculation and observations of living organisms can be assessed to support one side or the other (Watanabe 2005). Experiments involving metabolic rates and parental behavior have been conducted, as well as observations of other ectothermic organisms such as pythons and fish that give support both for and against the above stated hypothesis. In one experiment in the 1950’s by Raymond Cowles, a zoologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, fur coats were put on monitor lizards to insulate them, but it turned out they had no effect on the temperature of the animal (Watanabe 2005). Rather, the extra layer would inhibit the ability to absorb heat by basking; later, it was deemed that in order to evolve endothermy, possession of insulation would be a must, nixing the idea of lizards ever being endothermic (Watanabe 2005). Contrary to this experiment was one carried out in which the aerobic scopes of alligators were measured, and in conclusion, it was found that their aerobic scopes were measured too high to be considered ectotherms, yet too low to be endotherms (Watanabe 2005). Finally, Seymour proved that from their four-chambered heart (that they have in common with other endotherms), crocodile embryos could separate venous and arterial blood supplies to create high systolic blood pressure (Watanabe 2005). Along with high metabolic rates, this gave him reason to believe crocodiles were once endothermic (Watanabe 2005). I cannot say that I know enough to make a positive decision about whether crocodilians really were once endotherms and then re-evolved into ectotherms, but based on Seymour’s data, I can confidently say that it is a great possibility that crocodilians went back to being ectothermic after being endothermic. It can be compared to the evolution of aquatic mammals: giving a short and condensed version, it is known that quadrupeds (and later mammalian quadrupeds) evolved on land from aquatic organisms, and over time, became mammals. Eventually, these terrestrial organisms found their way back to the aquatic life, only this time, they were more complex and could produce live young and nurse them underwater. To me, this is a very interesting concept. What pressures caused these terrestrial organisms to go back to where they first came from after slowly adapting to terrestrial life, and why was it advantageous? The same kinds of questions arise in regards to crocodilians being endotherms. Perhaps at one point endothermy was advantageous, only to later become detrimental, causing a shift to ectothermy. Like Seymour mentions, the only way in which this issue can be solved is by genetic and paleontological research and discovery. To me though, it is hard to believe the hypothesis that crocodilians have only been, and always will be, ectothermic.