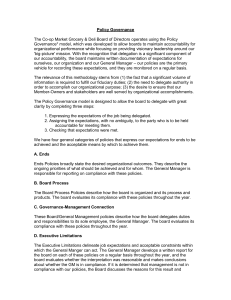

Improving governance and accountability in the school system

advertisement