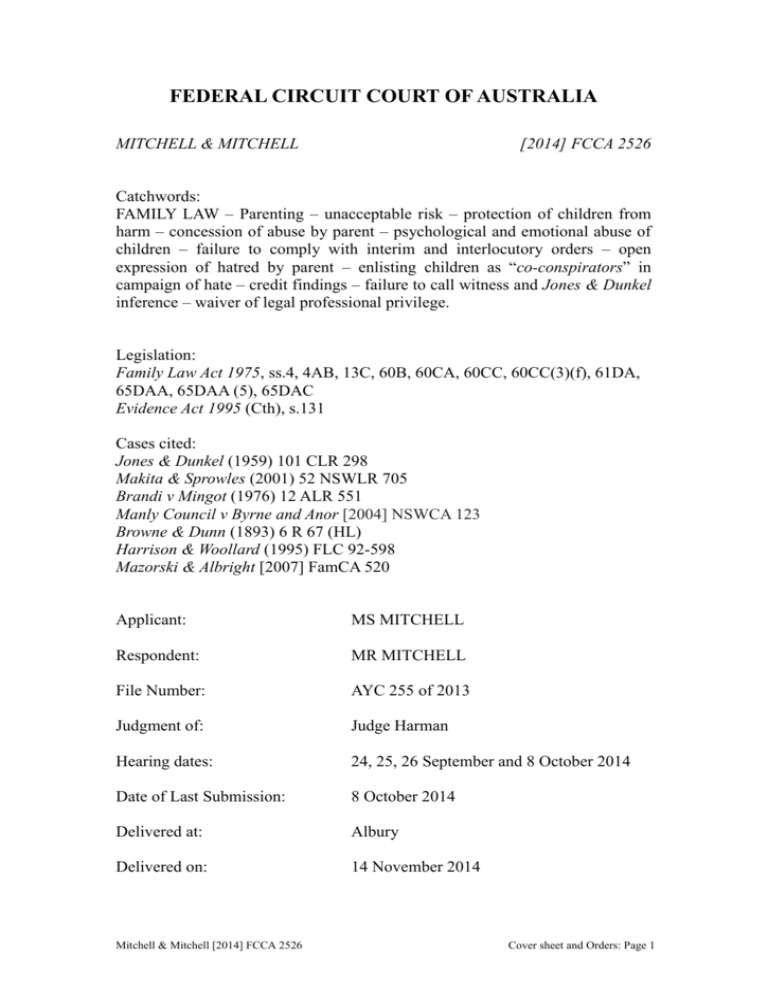

Decision - Family Law Express

advertisement