Crystal, D. 2010. A Little Book of Language. New Haven : Yale

advertisement

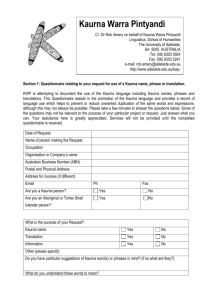

Crystal, D. 2010. A Little Book of Language. New Haven : Yale University Press. Dying languages Speaking, writing, and signing are the three ways in which a language lives and breathes. They are the three mediums through which a language is passed on from one generation to the next. If a language is a healthy language, this is happening all the time. Parents pass their language on to their children, who pass it on to their children … and the language lives on. Languages like English, Spanish, and Chinese are healthy languages. They exist in spoken, written, and signed forms, and they’re used by hundreds of millions of people all over the world. But most of the 6,000 or so of the world’s languages aren’t in such a healthy state. They’re used by very few people. The children aren’t learning them from their parents. And as a result the languages are in real danger of dying out. When does a language die? A language dies when the last person who speaks it dies. And this is happening in many parts of the world. There are several dozen languages which have only one speaker left. And several more where the speakers are just a few dozen or fewer. For example, many of the languages spoken by the tribal peoples of Brazil or Indonesia have only a handful of speakers. Languages which have only a few speakers, and which are likely to die out soon, are called endangered languages. Most of the world’s endangered languages are spoken in countries on either side of the equator. There are hundreds of languages spoken in south-east Asia, in such countries as Papua New Guinea. Hundreds more are spoken across India and Africa. Many more are in South America. These are the places where languages are dying out very quickly. But we can find endangered languages anywhere. Most of the Aboriginal languages of Australia are endangered. And so are the Celtic languages of Britain, Ireland, and France. Fewer and fewer people speak Gallic, the Celtic language of Scotland. And the last native speakers of Manx, the language of the Isle of Man, died out a few decades ago. Perhaps half the languages of the world are going to die out in the next 100 years. That’s 3,000 languages disappearing in 1,200 months. If we work out the average, we’ll find that there’s a language dying out somewhere in the world every two weeks or so. This is much faster than anything that’s happened in the past. There’s nothing new about a language dying. Languages have always disappeared when the people who spoke them died out. Two thousand years ago there were many languages spoken throughout the Middle East that no longer exist today. Think of all the peoples who invented the writing systems that I described in Chapter 16, such as the Hittites, the Assyrians, and the Babylonians. Those cultures came and went, over thousands of years, as one defeated another, and the languages disappeared along with the peoples. We know something about these ancient languages because some of them were written down. Unfortunately, many languages of the past were never written down, so they are lost for ever. That’s still the case today. About 2,000 of the world’s languages have never been written down. If they die before linguists get a chance to record them, they too will be gone for ever. When a culture dies out, it leaves behind evidence of how the people lived. Archaeologists can dig up all sorts of things – pots, skeletons, boats, coins, weapons, bits of houses – but spoken language leaves nothing behind when it disappears. After all, as we saw in Chapter 4, speech is only vibrations in the air. So when a spoken language dies which has never been recorded in some way, it is as if it has never been. There’s nothing unusual about a single language dying. But what’s going on today is extraordinary, when we compare the situation to what has happened in the past. We’re seeing languages dying out on a massive scale. It’s a bit like what’s happening to some species of plants and animals. They’re dying out faster than ever before. Why is this? Plants and animals die out for all sorts of reasons, such as changes in climate, the impact of new diseases, or changes in the way people use the land. And some of these reasons apply to languages too. A natural disaster, such as an earthquake or a tsunami, can destroy towns and villages, and kill many people. But if the people are dead, or if their community is devastated, then their language will die out too. Humans can be the cause of language death. Hunters can kill all the remaining animals in a species. Collectors can take all the remaining plants. And governments can stop people using their language – as we saw in Chapter 13. If a language is banned, and the children are forbidden to learn it, it will soon die out. But the main reason that so many languages are endangered is not as sudden or as dramatic as a tsunami or a banning. In most cases, the people stop using their first language simply because they decide to use a different one. This is why, for example, most people in Wales speak English or most people in Brittany speak French. Over the years, families have gradually stopped using one language and started using another. Why have they done this? It’s usually because the new language promises them a better kind of life. In particular, they’ll get a better job if they learn the new language. Think of all the ‘best jobs’ in the country where you live. How many of them would you be able to do if you didn’t speak the main language of the country? None of them. Now imagine being a member of a small tribe in Africa, America, or Australia a few hundred years ago, when the British, Spanish, and others were colonizing the world. In come the colonists with their guns and new ways of life, and they take over your country. They’re in charge, so if you want to get on, in the new society, you’ve just got to learn their language. And when that happens, it’s very easy to let your old language slip away. Your children don’t bother with it, because the new language is the really useful one. It’s fashionable. It’s cool. Your old language is definitely uncool. And gradually, it falls out of use. It doesn’t have to be that way. People can learn a new language without having to lose their old one. That’s what bilingualism is all about, as we saw in Chapter 13. Bilingualism lets you have your cake and eat it. The new language opens the doors to the best jobs in society; the old language allows you to keep your sense of ‘who you are’. It preserves your identity. With two languages, you have the best of both worlds. These days, in many countries, people have come to realize this. They see the importance of preserving the language diversity of the world, just as they see the importance of preserving the diversity of plants and animals. The world governing bodies, such as the United Nations, have repeatedly drawn attention to the issue. It isn’t enough just to preserve the ‘tangible’ heritage of the Earth – all the physical things we can see around us in the landscape, such as deserts, forests, lakes, monuments, and buildings. It’s also important to preserve the ‘intangible’ heritage – all the things which show how we live, such as music, dance, theatre, painting, crafts, and especially languages. How do we preserve languages? Three factors have to be present for this to happen. The people themselves must want their language to survive. The government of their country must want to help them. And money has to be found to keep the language going. It’s an expensive business. The language has to be documented – that is, written down and described in grammars and dictionaries. Teachers have to be trained, books published, street signs put up, community centres established, and lots more. But when all three factors are in place, amazing things can be done. New life can be brought into a language. The term is revitalization. The language is revitalized. We’ve seen it happen several times over the past 50 years. Probably the most famous case is the revival of Hebrew to serve as the official language of modern Israel. Welsh, too, has done very well, after a long period of decline. Today the number of speakers is increasing, and its presence can be seen on street signs and in railway stations and wherever you travel in Wales. In New Zealand, the Maori language has been kept alive by a system of ‘language nests’. These are organizations that provide children under five with a homely setting in which they are intensively exposed to the language. The staff are all Maori speakers from the local community. The hope is that the children will keep their Maori skills alive after leaving the nests, and that as they grow older they will in turn help new generations of young children to learn the language. Even an extinct language can be brought back to life, if conditions are right. It must have been written down and described, or audiorecorded in some way, and the people must want it back. This has happened with an Aboriginal language of South Australia called Kaurna. The last native speaker died in 1929, but in the 1980s a group of Kaurna people decided that they wanted their language back. ‘The language isn’t dead,’ they said, ‘it’s only sleeping.’ Fortunately, material survived from the nineteenth century so that a linguist was able to make a fresh description and help the Kaurna people start learning the language again. It’s taught in schools now. One day, perhaps, some children will start learning it as their mother tongue. One of the jobs the linguist had to do was bring the vocabulary up to date. The old Kaurna language had no words for television or mobile phones! That’s the thing about a language: it never stands still. When we study language, one of the most important topics is to investigate the way languages change. Parrot Talk In 1801, an explorer called Alexander von Humboldt was searching for the source of the Orinoco river in South America. He met some Carib Indians who had recently attacked a neighbouring tribe. They’d killed all the people, but they’d brought the tribe’s parrots back home with them. The parrots chattered away, like parrots do. And when von Humboldt heard them talk, he realized that they were speaking the language of the murdered Indians. He decided to write the words down, to capture the sound of the language. There were no human speakers of the language left. The parrots were all he had to go on. Nearly 200 years later, an American sculptor called Rachel Berwick decided to make the language come alive again. She got two South American parrots and taught them to say some of the words that von Humboldt had written down. Then she put them in a large cage surrounded by foliage and jungle noises, and displayed them in a gallery. The parrots happily chattered away. Suddenly, the old language came alive again. Even though it was only parrot-talk, hearing it sent shivers down the back of your neck.