Holistic Success - The Swiss Connection

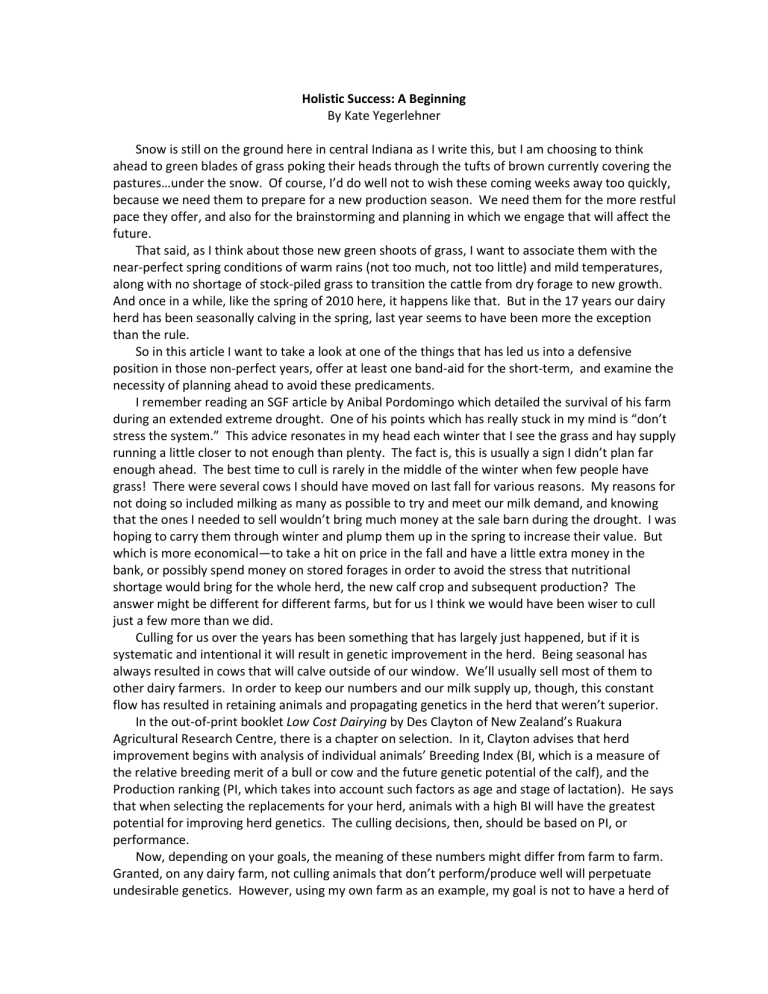

Holistic Success: A Beginning

By Kate Yegerlehner

Snow is still on the ground here in central Indiana as I write this, but I am choosing to think ahead to green blades of grass poking their heads through the tufts of brown currently covering the pastures…under the snow. Of course, I’d do well not to wish these coming weeks away too quickly, because we need them to prepare for a new production season. We need them for the more restful pace they offer, and also for the brainstorming and planning in which we engage that will affect the future.

That said, as I think about those new green shoots of grass, I want to associate them with the near-perfect spring conditions of warm rains (not too much, not too little) and mild temperatures, along with no shortage of stock-piled grass to transition the cattle from dry forage to new growth.

And once in a while, like the spring of 2010 here, it happens like that. But in the 17 years our dairy herd has been seasonally calving in the spring, last year seems to have been more the exception than the rule.

So in this article I want to take a look at one of the things that has led us into a defensive position in those non-perfect years, offer at least one band-aid for the short-term, and examine the necessity of planning ahead to avoid these predicaments.

I remember reading an SGF article by Anibal Pordomingo which detailed the survival of his farm during an extended extreme drought. One of his points which has really stuck in my mind is “don’t stress the system.” This advice resonates in my head each winter that I see the grass and hay supply running a little closer to not enough than plenty. The fact is, this is usually a sign I didn’t plan far enough ahead. The best time to cull is rarely in the middle of the winter when few people have grass! There were several cows I should have moved on last fall for various reasons. My reasons for not doing so included milking as many as possible to try and meet our milk demand, and knowing that the ones I needed to sell wouldn’t bring much money at the sale barn during the drought. I was hoping to carry them through winter and plump them up in the spring to increase their value. But which is more economical—to take a hit on price in the fall and have a little extra money in the bank, or possibly spend money on stored forages in order to avoid the stress that nutritional shortage would bring for the whole herd, the new calf crop and subsequent production? The answer might be different for different farms, but for us I think we would have been wiser to cull just a few more than we did.

Culling for us over the years has been something that has largely just happened, but if it is systematic and intentional it will result in genetic improvement in the herd. Being seasonal has always resulted in cows that will calve outside of our window. We’ll usually sell most of them to other dairy farmers. In order to keep our numbers and our milk supply up, though, this constant flow has resulted in retaining animals and propagating genetics in the herd that weren’t superior.

In the out-of-print booklet Low Cost Dairying by Des Clayton of New Zealand’s Ruakura

Agricultural Research Centre, there is a chapter on selection. In it, Clayton advises that herd improvement begins with analysis of individual animals’ Breeding Index (BI, which is a measure of the relative breeding merit of a bull or cow and the future genetic potential of the calf), and the

Production ranking (PI, which takes into account such factors as age and stage of lactation). He says that when selecting the replacements for your herd, animals with a high BI will have the greatest potential for improving herd genetics. The culling decisions, then, should be based on PI, or performance.

Now, depending on your goals, the meaning of these numbers might differ from farm to farm.

Granted, on any dairy farm, not culling animals that don’t perform/produce well will perpetuate undesirable genetics. However, using my own farm as an example, my goal is not to have a herd of

really high-producing cows. I want animals that will give a moderate amount of milk, high levels of butterfat and protein, and will maintain or increase their body condition over the course of their lactation.

Another thing Clayton writes that I hadn’t thought about before is not necessarily selecting the first calves born to keep for replacements. He says that if you have say a 6 week calving interval, hold on to all your best heifer calves until those six weeks are through and then select the calves from all your top cows (and don’t forget the importance of the sire) within that window. I think about the first calves born as being from the most fertile cows, and that may be true, but there may also be some low-end producers up front that always breed quickly. So pick calves from your top cows that will result in overall genetic improvement toward your goals.

To switch gears back to the pasture side of things, one of my goals is to get to the place where I have enough stockpiled forage to carry the herd through the winter with minimal hay feeding, through the transition of lush spring growth until dry matter begins increasing. I suspect hay will have to buffer that transition yet again this spring, but better hay than no buffer at all. Metabolic imbalances are a threat to many dairies, and my observations over the past several years have given me a clue into one way to prevent these destructive disorders.

There have been some years when we didn’t have enough stockpiled grass, and when new growth started coming, we were rotating cows through the pastures quickly. Too much protein and not enough dry matter leads to imbalance, and it seems to be accentuated when the weather is chilly and cloudy. I think the only times we have had cases of milk fever in our 100% grass-fed years have occurred when the freshening cows (usually the higher producers) have been on a diet of short green grass in chilly weather. A couple years ago when I recognized this pattern, I made sure there was a bale of hay to supplement the grass and we haven’t had another case of milk fever since.

That’s the band-aid. The cure is more along the lines of looking at the system as a whole, planning and making decisions that will keep you and your cows away from the precipice altogether!

Another issue spring graziers deal with is off-flavors in the milk. I believe that this same strategy of balancing the diet addresses that too. We used to notice it quite a bit in the spring…the strong grassy taste, or the wild onion and garlic cows like to munch on. Though it didn’t seem to come through in the cheese, the smell and taste of the fluid milk was rather offensive to some. But having adequate dry matter available for the cows seems to really minimize this. I haven’t noticed it much at all the last few years.

There are many out there who are much more knowledgeable than I am about how this all works, but I am guessing it has something to do with an excess of protein in the diet. I am aware that overfeeding of protein can result in elevated levels of urea in the blood. Urea will diffuse into mammary cells until the concentrations are equalized in the blood and milk. I’m not sure whether this excess protein results in a “leaky” cell wall that might allow the flavonoids into the milk or if it’s something else, but the bottom line is that balancing the animal’s nutritional needs seems to circumvent the process. Again, look at the big picture and see how different decisions earlier can address the needs of the whole, not just put a band-aid on one problem.

Over the course of this past year I have at times gotten discouraged at the problems we have been battling on our farm. It is difficult when you read and learn and implement and then experience some degree of failure or another, isn’t it? But I am still learning, and right now I’m learning that even though we have been trying good things, we’ve limited ourselves in scope, and the parts we’ve not been seeing are hindering success. It’s more than just cattle, or grazing, or cattle and grazing, or any other part of what we’re trying to do. Life doesn’t come in compartments and sections. It’s a whole, and everything is connected to and affected by everything else. If we want to be successful economically, ecologically, and socially for more than just a little while we will

do well to recognize that it won’t just happen. It takes careful planning and wise decision-making, along with flexibility and humility when we find out we didn’t know as much as we thought we did.