Trinity-Solice-Rothenbaum-Aff-D3 Districts

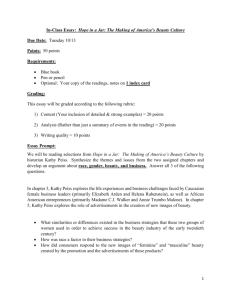

advertisement