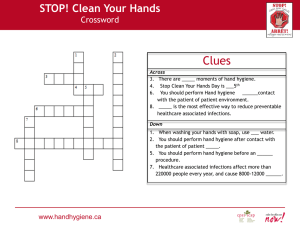

Review of Related Literature Hand hygiene is a general term

advertisement

Review of Related Literature Hand hygiene is a general term referring to any action of hand cleansing, or any physical or mechanical action of removing dirt, organic material, and/or microorganisms, (WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Healthcare). Different hand hygiene practices are being utilized. It could either be through hand washing with plain soap or antimicrobial soap/or an antiseptic and water, requiring drying of the hands with a towel or any devices, or through application of an antiseptic handrub without requiring any rinsing. Plain soaps are detergents that contain no added antimicrobial agents as active component. It can only remove a certain level of microbes and other contaminants on the skin with the aid of water. Antimicrobial soaps are medicated detergents containing an antiseptic agent at a concentration enough to inactivate or inhibit the growth of the skin’s microbial flora. Its detergent component can remove these contaminants like plain soap. Antiseptic hand rubs are alcohol-based preparations directly applied to the skin without requiring any rinsing, to reduce and inactivate and/or temporarily inhibit the growth of microorganisms. The human skin is populated by microbes classified either resident or transient flora. Different areas of the body have varied total aerobic bacterial counts, and the total bacterial counts on the hands of a medical personnel have ranged from 3.9 x 104 to 4.6 x 106, (The Journal of Investigative Dermatology (1950), 305–324). The resident flora are mostly associated with the deeper layers of the skin which includes the sebaceous glands. For this reason, resident organisms such as coagulase-negative Staphylococci, Corynebacterium spp, and Propionibacterium spp rarely cause infection and are inaccessible to hand hygiene preparations. On the other hand, transient flora involves microorganisms frequently associated with nosocomial infection and they colonize the more superficial layers of the integument. These microorganisms are usually acquired by medical personnel through direct contact with patients and surfaces within close proximity of the contaminated patient. Thus, these microbes are less adherent and can either be removed by good hand hygiene or can easily be transmitted to others if not immediately eliminated. Hands of some medical personnel may be persistently contaminated with various pathogenic flora such as S. aureus, Gramnegative bacilli, or yeast. According to the WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Healthcare, there are 5 sequential steps of transmission of health-care associated pathogens from one patients to another via healthcare worker’s hands: 1) Organisms are present on the patient’s skin, or have been shed onto inanimate objects immediately surrounding the patient; 2) Organisms are be transferred to the hands of HCWs; 3) Organisms must be capable of surviving for at least several minutes on HCWs’ hands; 4) Handwashing or hand antisepsis by the HCW is inadequate or entirely omitted, or the agent used for hand hygiene is inappropriate; and 5) The contaminated hand or hands of the caregiver came into direct contact with another patient or with an inanimate object that will come into direct contact with the patient. The direct objective of hand hygiene practices is to reduce the transient microbial flora without necessary removing the resident skin flora. Indirectly, transmission of microorganisms to patients, equipment, or another health worker is reduced. Various hand hygiene studies have provided evidence that adherence to hand hygiene practices resulted in a decrease in transmission of infection to patients. The risk of acquiring health care associated infection (HCAI) is universal and occurs in every health-care facility and system around the world. Overall estimates indicate that more than 1.4 million patients worldwide in developed and developing countries are affected at any time. It should be considered as a major problem, and its prevention must be a priority. The effect of HCAI are prolonged hospital stay, long-term disability, increased resistance of microorganisms to antimicrobials, massive additional financial burden, high costs for patients and their families, and excess deaths. Various studies reported that HCAI rates are higher in developing countries than in developed countries. HCAI cases were also reported to be more severe in high-risk populations such as adults in ICUs and neonates. Such infection was found to be more prevalent in developing countries. Neonatal infections were reported to be 3-20 times higher among hospital-born babies in developing countries than in developed countries. A device-associated infection rates reported from multicentre studies conducted in adult and pediatric ICUs are compared with the USA NNIS system rates in this table: Unfavorable contributing factors such as understaffing, poor hygiene and sanitation, lack or shortage of basic equipment, and inadequate structures and overcrowding, almost all of which can be attributed to limited financial resources; unfavorable social background and a population largely affected by malnutrition and other types of infection and/or diseases are considered to contribute to the increased risk of HCAI in developing countries. Thus, the various preventive measures to reduce HCAI prevalence have been identified and proven effective, such as hand hygiene, and WHO recommends that infection control must reach a higher position among the first priorities in national health programs especially in developing countries. The WHO developed a Guideline on Hand Hygiene in Healthcare, and was published last 2004. It adopted the CDC Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings issued in 2002 as the basis. Further revisions and additional topics were made subsequently. The finalized guideline was published last 2008. The present guidelines were developed by the “Clean Care is Safer Care” team, and it conceived a global perspective of hand hygiene; strongly supported by well-designed experimental, clinical, or epidemiological studies, and has a strong theoretical rationale; therefore is strongly recommended in every health-care facility worldwide. Consensus recommendations from the WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Healthcare include the following as indications for hand hygiene: A. Wash hands with soap and water when visibly dirty or visibly soiled with blood or other body fluids or after using the toilet. B. If exposure to potential spore-forming pathogens is strongly suspected or proven, including outbreaks of Clostridium difficile, hand washing with soap and water is the preferred means. C. Use an alcohol-based handrub as the preferred means for routine hand antisepsis in all other clinical situations described in items D (a) to D (f) listed below, if hands are not visibly soiled. If alcohol-based handrub is not obtainable, wash hands with soap and water. D. Perform hand hygiene: a. before and after touching the patient; b. before handling an invasive device for patient care, regardless of whether or not gloves are used; c. after contact with body fluids or excretions, mucous membranes, non-intact skin, or wound dressings; d. if moving from a contaminated body site to another body site during care of the same patient; e. after contact with inanimate surfaces and objects (including medical equipment) in the immediate vicinity of the patient; f. after removing sterile or non-sterile gloves; E. Before handling medication or preparing food perform hand hygiene using an alcohol-based handrub or wash hands either with plain or antimicrobial soap and water. F. Soap and alcohol-based handrub should not be used concomitantly; Hand hygiene technique A. Apply a palmful of alcohol-based handrub and cover all surfaces of the hands. Rub hands until dry. B. When washing hands with soap and water, wet hands with water and apply the amount of product necessary to cover all surfaces. Rinse hands with water and dry thoroughly with a single-use towel. Use clean, running water whenever possible. Avoid using hot water, as repeated exposure to hot water may increase the risk of dermatitis. Use towel to turn off tap/faucet. Dry hands thoroughly using a method that does not recontaminate hands. Make sure towels are not used multiple times or by multiple people. C. Liquid, bar, leaf or powdered forms of soap are acceptable. When bar soap is used, small bars of soap in racks that facilitate drainage should be used to allow the bars to dry. D. However, risk factors for noncompliance with hand hygiene have been determined in several observational studies with an aim to improve compliance. Factors said to influence reduced compliance are being a physician or a nursing assistant, male gender, working in an intensive care unit, working during weekdays, wearing gown and gloves, using an automated sink, performing activities with high risk for crosstransmission and having many opportunities for hand hygiene per hour of patient care. In another hospital based survey, variables were identified. These included professional category, hospital ward, time of day or week, and type and intensity of patient care. Compliance was highest during weekends and among nurses. Noncompliance was higher in ICUs than in internal medicine, during procedures with a high risk for bacterial contamination, and when intensity of patient care was high. Compliance with hand washing worsened when the demand for hand cleansing was high. Similarly, the lowest compliance rate was found in ICUs, where indications for hand washing were typically more frequent. This study confirmed modest levels of compliance with hand hygiene in a teaching institution and showed that compliance varied by hospital ward and type of health-care worker. This further suggests that targeted educational programs may be useful. The study suggested that full compliance with current guidelines may be unrealistic. However, facilitated access to hand hygiene could help improve compliance. Monitoring of hand hygiene practices have been a part of hospitals like the Santo Tomas University Hospital as seen in past studies and the work of the Center (it is committee ands not center) for Hospital Infection Control (CHIC). In the health care setting, there is a difference between knowledge of hand hygiene modalities and hand hygiene habits. Compliance to this is affected by several factors as mentioned in a review from the International Journal of Infectious Diseases: Hand hygiene: simple and complex Review by Michael Ellis International Journal of Infectious Diseases (2005) Hand hygiene practices are composed of various factors, thus, making monitoring and guideline construction very challenging. There are almost no standardized methods for many aspects of hand hygiene and, therefore, it is very difficult to make comparisons between studies. The researchers see fit that an own study for the medical clerks rotating in the Santo Tomas University Hospital be done to facilitate the composition of the hospital’s guidelines on hand hygiene and to improve the compliance of the medical clerks on hand hygiene practices. In a study made on hand hygiene compliance from 1981 to 1999, compliance was estimated to be only less than 50%. Compliance with hand hygiene recommendations varies between hospital wards, among professional categories of health-care workers, and according to working conditions. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) created guidelines in 1981 stating that hand washing should always occur before performing invasive procedures, before and after contact with wounds, before contact with susceptible patients, and after contact with a source suspected to be contaminated. Though this standard in hand washing has been defined, promotion of hand hygiene continues to be a major challenge to infection control experts. Lack of scientific information on the definitive impact of improved hand hygiene on hospital infection rates has been reported as a possible barrier to adherence with recommendations. Hospital infections have been recognized for more than a century as a critical problem affecting the quality of patient care provided in hospitals. Studies have shown that at least one third of all hospital infections are preventable. Infections resulting from cross-contamination and transmission of microorganisms by the hands of health-care workers are recognized as the main route of spread. Recent studies showed results of a successful hospital wide hand hygiene promotion campaign, with emphasis on hand disinfection. This resulted in sustained improvement in compliance associated with a significant reduction in hospital infections. Although additional scientific and causal evidence is needed for the impact of improved hand hygiene on infection rates, studies showed that improvement in behavior reduces the risk of transmission of infectious pathogens. Strategies for successful promotion of proper hand hygiene involve a combination of education, motivation and system change. Various psychosocial parameters influencing hand hygiene behavior include intention, attitude toward the behavior, perceived social norms, perceived behavioral control, perceived risk of infection, habits of hand hygiene practices, perceived model roles, perceived knowledge, and motivation. Factors necessary for change include dissatisfaction with the current situation, perception of alternatives, and recognition, both at the individual and institutional level, of the ability and potential to change. While the last factor implies education and motivation, the former two necessitate primarily a system change. Bibliography Huang D and Zhou J. Effect of intensive handwashing in the prevention of diarrhoel illness among patient with AIDS: a randomized controlled study. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2007: 56, 659-663. Rumbaua R, Yu C and Pena A. A point-in-time observational study of hand washing practices of healthcare workers in the Intensive Care Unit of St. Luke’s Medical Center. Phil J Microbiol Infect Dis 2001: 30, 3-7. Larson E. Evaluating handwashing technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1985: 10, 547-552. Larson E. APIC Guideline for hand washing and hand antisepsis in health-care settings. Am J Infect Control 1995: 23, 251-269. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. WHO press 2009, Switzerland. Ellis M. Hand hygiene: simple and complex. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2005.