Detracking Proposal

advertisement

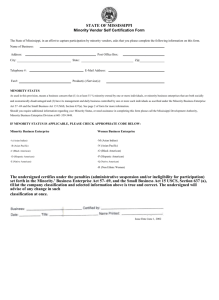

Keren Ong Statement of problem: Tracking in schools produce, reproduce, and perpetuate inequality in the classrooms and in society. Lower income students and language minority students are often placed in the lower tracks that prepare them for vocational jobs instead of the college prep classes that are offered to the higher track students (Conchas, 476). It is assumed that these lower track students will not be able to do well in college or achieve much academic success, so the classes they are offered are geared towards them working once they graduate high school. In the current tracking system, placement into tracks often is based off of race and social class with a large and unequal representation of lower class and minority cultures in the lower classes and white middle class students in the higher classes (Rubin, 649). Language is often tied to the distribution of privilege in society because of how it is tied to identity (McCarty, 661, 666, Garcia, 82). Generally, the people who speak a minority language are not from the United States and are not seen as being fully integrated into this society yet. They generally come into the United States in order to fulfill the American dream of working hard and moving up in society. English is therefore seen as the language of modernity and social upward mobility by a significant amount of people including language minority speakers (McCarty, 672). Because of this, minority languages are threatened and language policy must also be created to prevent other languages from dying out (Garcia, 99). The placement of language minority speaking students into lower tracks currently reflect the value that many schools have of minority languages. Because these language minority students are unable to speak English, they are seen as less capable of doing well in society and therefore placed into lower tracks. Furthermore, the focus on English Acquisition for language minority students actually constrains what they can achieve (Billings, 386). Because these English Language Learners may be separated from their peers and placed in classes specifically for English acquisition, they are denied access to grade level content and highly prepared teachers (Billings, 386). The peers who are in the regular classes also miss out on the opportunity to learn from the different culture of the minority students. Along with missing out on grade level content to focus on learning English, language minority student also face unqualified teachers, inferior equipment, and peer groups that do not necessarily support academic achievement in the lower tracks that they are placed in (Conchas, 476). Low teacher expectations of students lead to less challenging curriculum which does not help the students academically. Research has shown that lower achieving students placed in lower tracks often do worse academically than if they had been placed in a mixed class (Rubin, 650). This may be because low teacher expectations of these students prevent the teacher from introducing new or challenging material. Low teacher expectation might also hurt the students’ self esteem and prevent them from trying harder in school if the authority figures in their lives continually show them that they do not think they can succeed. These lower achieving students end up adapting to these hostile learning conditions and lower their aspirations about what they can achieve and their chances of social mobility in the future (Foley, 388). It may seem like there is no reason to work hard if there are so many factors working against the students’ success and teachers and a system that don’t care about them and where they come from. They may see achieving academic success as selling out their own cultural or racial heritage (Foley, 387). In order to prevent the perception of selling out, students rebel against the majority culture and purposely do not work towards academic success. Conchas quotes a research study where second generation Latino students reject schools and turn to youth gangs (Conchas, 478). Peers in gangs may also negatively affect a student’s success in school. The peer groups that students are a part of greatly affect the amount of time they spend studying and eventual school success (Oseguera et al, 1156). As students go through school, peer groups and friends are heavy influences on students’ behaviors and habits and a studious peer group may positively influence a student in the same way that a rebellious peer group may negatively influence a student’s success. The current system of tracking actually detracts from minority students success and all of these factors contribute to the lower achievement of the lower track students. Proposal: Provide grants for school districts to eventually detrack all subjects in their middle schools and high schools over a 7 year period. In the first year the policy is implemented, the students in the incoming 6th grade class will be randomly assigned to detracked classes for all subjects. This will start the detracked program in the school. After the first year, the 7th grade classes along with the 6th grade classes will be detracked. Each grade that the first class of detracked students who started the policy enter will be detracked. Each incoming grade level following the first class of detracked students will also be detracked. When the first class of detracked students graduate, both the middle school and high school will be fully detracked. Provide funding for teacher training and professional in how to run a detracked program Schools that apply for the grant must show evidence or reasonable belief that implementing a detracked program for their school will benefit the students. The purpose of this proposition is to: 1) how schools should work with families from diverse backgrounds in order to enhance learning experience of their children. Increase parent participation and agency in schools. Through teacher education and training, teachers will be taught to understand the immense diversity of different immigrant cultures and learn appropriate steps to include the parents in the schooling process. Teachers need to take into consideration the family’s work schedule, varying family situations, and linguistic needs when working with the parents (Doucet, 2729). In general, teachers are working with the system, speak English, and are in the position of teaching children and thus have a position of power over the parents of the children who do not know how to navigate the system and do not speak English. They will be educated about the power dynamics that come when working with a parent and understand that sometimes a loss of power is necessary to hear the voice of the parent to benefit the teaching of the child (Doucet, 2728). In a detracked school program, the teacher will have to constantly be aware of the diversity of the students and how they can include parents of the students in the learning process to better enhance the learning experience for the students. 2) challenge stereotyped categories of students Counter misconceptions that language minority speaking students are less capable of achieving academic success and need to be separated from their peers and placed into separate classes for English acquisition. In Rubin’s case study of three different high schools that implemented detracking, she confirms the correlation between teacher expectation and student performance. In the school where teacher expectation of the students were low and it was believed that the students were unmotivated, even in the detracked classroom, there were multiple factors that prevented students from achieving academic success like low curriculum and poor teaching (Rubin, 688). On the other hand, in a classroom where it was expected that all of the students would go to college, the detracked classroom was intellectually engaging and challenging while the quality of the instruction was boosted by the different levels of students in the classroom (Rubin, 689). Unfortunately, this engaging and challenging classroom was only accessible to the dominant white middle class students. Just like in the study of the elementary school and the strand bilingual education program offered in Palmer’s article, innovative and beneficial programs have generally been reserved for the benefit of the dominant group of students (Palmer, 95,109). These case studies show that it is not the students themselves that solely determine how well they do in school but is also based on teacher beliefs and the policies surrounding their education. Palmer specifically calls for working with the dominant and minority cultures in order to ensure equitable access for linguistic minorities and dominant groups (Palmer, 110). 3) role of language in educational achievement of all students, educational achievement of linguistic minority students Help ensure that typically low achieving students and students who speak a minority language are offered the chance to an equitable education that provides rigorous and challenging curriculum. Providing a multicultural teaching curriculum that benefits all students in a detracked classroom including linguistic minority students requires the teacher to find different styles of teaching to reach all students. As Heath studies different schools and the different ways each group of students participate in literacy, she proves that there cannot be a one size fits all students way of teaching. Understanding the different ways that each student displays their knowledge and what they bring from their own cultural upbringing will ultimately benefit all students as they learn from each other’s different ways of displaying knowledge (Heath, 73). Banks also asserts that students should also “be given opportunities to investigate and determine how cultural assumptions, frames of references, perspectives, and the biases within a discipline influence the ways the knowledge is constructed,” (Banks, 11). Even as students learn from each other about the different knowledge that they bring to the classroom, students also need to be able to understand how their own knowledge they bring is affected by their culture and other perspectives. 4) culturally responsive education to promote equitable access for all students Ensure that a network of support is provided to students who are placed in a detracked program. Conchas uses the term social scaffolding to describe the support necessary for minority students to increase their chances for school success meant to familiarize students with organizational support provided by the school (Conchas, 479). In providing a system of support where low achieving students are put into relationships with high achieving friends and supportive teachers, the lower achieving students will be able to gain the access and help they desire and raise their chances of succeeding in school. This network should also reach across racial lines between the teachers and their minority students to help students understand the resources available to them. Challenges of Proposal: Highest achieving students do not do as well as they could with other higher achieving students in a detracked program. Research has shown that high achieving students do not achieve as highly as they could in a tracked class. Requires teacher commitment to teaching a detracked classroom and coming up with a challenging and rigorous academic curriculum. Requires a change in teacher belief of minority and low income students. Conclusion: The goal of this proposal is to mix different students from all backgrounds to benefit all of the students. Teachers will need to implement many different teaching methods based on the diversity of students to try to match the students’ cultural experiences with lessons in the classroom (Banks). All of these different lessons and different ways of learning benefit all of the students regardless of their own background (Heath, 73). Being exposed to different learning methods ultimately help the students who are able to work and learn through many different styles. This along with rigorous academic curriculum helps to raise teacher expectations of students and student self-esteem and academic achievement. Works Cited Banks, J A. (1993). The canon debate Billings, E. S., Martin-Beltrán, M., & Hernández, A. (2010). Beyond English Development Conchas, G Q. (2001). Structuring failure and success Doucet, F. (2011). (Re)Constructing Home and School: Immigrant Parents, Agency, and the (Un)Desirability of Bridging Multiple Worlds Foley, D. (2004). Ogbu’s theory of academic disengagement: Its evolution and its critics García, O. 2012. Ethnic identity and language policy Heath, S. B. (1982). What no bedtime story means McCarty, T. L., Romero-Little, M. & Zepeda, O. (2006). Native American youth discourses on language shift and retention Oseguera, L., Conchas, G. Q., & Mosqueda, E. (2011). Beyond Family and Ethnic Culture: Understanding the Preconditions for the Potential Realization of Social Capital Palmer, D. (2010). Race, power, and equity in a multiethnic urban elementary school with a dual-language "strand" program. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 41(1), 94-114 Rubin, B. C. (2008). Detracking in context