Top Management Team Dynamics as a Microfoundation of Adaptive

advertisement

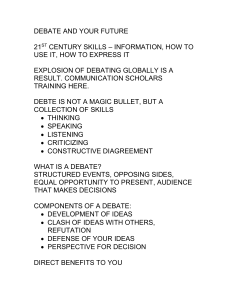

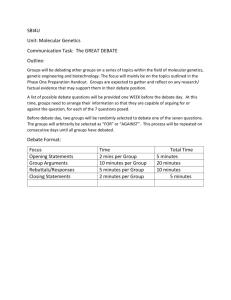

Top Management Team Dynamics as a Microfoundation of Adaptive Capability? This paper examines the effects of subsidiary TMT composition as a microfoundation of firm strategic adaptive capability and performance in a transition economy. Using a unique survey dataset of 107 MNC subsidiary firms in China, the paper investigates a path between TMT functional diversity and firm performance through increased adaptive capability. Unexpectedly, the results show that a functionally-diversity has no positive effect, however when functionally-diverse TMTs engage in debate, there is a significant positive impact on adaptive capability, and through this, performance. Our findings suggest that, as long as TMTs engage in debate, the benefits of functional diversity outweigh the potential costs of conflict and information-withholding leading to a positive and significant impact on adaptive capability. Conversely, without debate, the negative impact of functional diversity overshadows the benefits, and diversity does not contribute to adaptive capability or performance. Track: Strategy 1 Top Management Team Dynamics as a Microfoundation of Adaptive Capability? The capacity to transform internal organizational resources in response to environmental changes is consistently linked to sustained competitive advantage and therefore fundamental to management research (Hoopes & Madsen, 2008; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). To face this challenge firms must develop dynamic capabilities to reconfigure and adapt their existing resources (Teece & Pisano, 1998; Teece et al., 1997). Adaptive capability, a core dynamic managerial capability, reflects an organization’s capacity to reconfigure resources and adapt processes in an efficient and effective response to a changing environment (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004). It comprises the capacity to search for new opportunities, process relevant external and internal information and swiftly adapt organizational structure and processes (Oktemgil & Greenley, 1997; Staber & Sydow, 2002). Despite the recognised potential for adaptive capability to facilitate organizational success, most research in this area has not responded to recent calls to empirically investigate the mechanisms and circumstances conducive to its development (Zhou & Li, 2010). This parallels a significant research gap relating to the foundations of capabilities more generally (Felin, Foss, Heimeriks, & Madsen, 2012), which the current paper attempts to address by investigating microfoundations of adaptive capability (Felin & Foss, 2009). Across the strategy, organisational behaviour and human resource management literature, there is increased interest in the microfoundations of firm-level constructs in general (Felin & Foss, 2005; Felin & Hesterly, 2007). This is often articulated as the drive to better understand the individual and unit level constructs (Felin & Hesterly, 2007) and organizational processes and interactions (Teece, 2007), that comprise and cause higher-level strategic elements, such as capabilities (Abell, Felin, & Foss, 2008; Foss, 2011). 2 A promising, yet underexplored, perspective on the micro-foundations of capability development is derived from upper echelons theory, which suggests that top management team (TMT) characteristics influence, not only the overall strategic direction of organisations, but also decisions about the allocation of resources towards strategy implementation (Augier & Teece, 2009; Hambrick, 2007; Hambrick & Mason, 1984). TMTs make decisions based on member expertise and knowledge, and consistent with their experience-based perspectives (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). As these factors are strongly influenced by member’s job-related or demographic background (Smith, Smith, Olian, & Sims, 1994), it has been argued that TMT composition is likely to directly affect decision-making and the development of organizational capabilities (Buyl, Boone, & Matthyssens, 2011). Based on upper echelons theory, we suggest that TMT diversity potentially plays a significant role in the development of adaptive capability (Barney, 1991; Carpenter, Sanders, & Gregersen, 2001; Hitt, Bierman, Shimizu, & Kochhar, 2000). Building on past work demonstrating the leveraging role of team dynamics in realizing the benefit of diversity (Auh & Menguc, 2006; van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004), we further introduce debate processes as a moderator of functional diversity’s influence. Therefore, an important second aim of this study is to investigate the moderating effects of debate, defined as the questioning or challenging of others assumptions and direct and open presentation of rival hypotheses or recommendations (Simons, Pelled, & Smith, 1999), as a boundary condition that determines when diversity facilitates the development of adaptive capability. We predict and investigate a mediated path between TMT functional diversity, adaptive capability and firm performance, and specify debate as an important boundary condition of this pathway. This article is structured as follows: First, we describe the theoretical foundations underpinning the influence of TMT diversity and debate as a micro-level basis for dynamic capabilities, and adaptive capability in particular. We then develop our research model and 3 justify component hypotheses. Following this, we present our methodology and results and a discussion of our findings incorporating theoretical and practical implications. Theoretical Background The resource-based view links heterogeneous firm resources and capabilities to sustainable differences in firm performance (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). Valuable, non-imitable, rare and appropriable resources that are accumulated, combined and exploited create value and confer competitive advantage. Capabilities are organisational processes that allow resources to be deployed (Helfat & Winter, 2011) and dynamic capabilities, a special type of capability, allow firms ‘to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments’ (Teece & Pisano, 1997, p. 516). Dynamic capabilities, then, are higher-level processes of significant scale and scope embedded in firms (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Processes allowing acquisitions, alliances and new product development are examples of dynamic capabilities, which allow firms to alter the ways in which they earn their living (Helfat & Winter, 2011). Such major strategic moves involve the reconfiguration and manipulation of the firm’s resources into new valuecreating activities. These strategic decision-making processes have been labeled managerial adaptive capability, since they focus on managers’ resource reallocation decisions (Adner & Helfat, 2003; Kor & Mesko, 2013; Ma, Yao, & Xi, 2009). Building adaptive capability requires internal efforts and draws on internal firm-specific resources rather than market acquisitions. This makes it unique and largely inimitable and therefore a potential source of sustainable competitive advantage (Griffith & Harvey, 2001). Dynamic capabilities are the focus of much previous theoretical and conceptual discussion, but few empirical analyses have investigated the factors inside organizations that lead to the development of dynamic capabilities (Macher & Mowery, 2009). In particular, little research has detailed how individual and team characteristics affect the ability to 4 develop or leverage dynamic capabilities (Adner and Helfat, 2006; MacCormack and Iansiti, 2009), despite growing interest in how this may occur and the potential contribution of managerial skills and experience (Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009; Augier and Teece, 2009; Rothaermel and Hess, 2007). A promising approach to integrating research on the impact of managerial attributes and the development of dynamic managerial capabilities lies in the study of capability microfoundation (Felin & Foss, 2006). A microfoundations approach conceives capabilities as collective constructs, the explanation of whose development requires consideration of lower-level factors. Microfoundations of organizational capabilities therefore encompass their constituent components, such as individuals and processes, and the interactions. In particular, the role of individuals is crucial to understanding capabilities and their development (Felin and Hesterly, 2007). Substantial previous research has highlighted the importance of individuals to organizational performance (Felin & Hesterly, 2007) and provides consistently support for the important role of managerial cognition in individual, TMT and firm behavior (Gavetti, 2005; Naranjo-Gil, Hartmann, & Maas, 2008; Tripsas & Gavetti, 2000). Dynamic capabilities generally, and adaptive capability specifically, are impacted by the firm’s environmental turbulence, instability and uncertainty (Baum & Wally, 2003; Teece & Pisano, 1997), which produce deficits in the information needed by managers to identify and understand cause-and effect relationships (Carpenter & Fredrickson, 2001). In this context, individuals differing perspectives, beliefs and interests affect their decision-related choices as does their human capital (knowledge, skills and cognitive capacity) (Felin et al., 2012). The demographic and occupational profiles of TMTs, particularly the extent to which these profiles reflect a diversity of backgrounds and experiences, are therefore potentially related to capability development and subsequent performance outcomes (Certo, Lester, Dalton, & Dalton, 2006; Hambrick, Cho, & Chen, 1996). 5 Upper echelons research and reviews of team diversity have differentiated between two analytical perspectives, both of which have been applied to top management teams (van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Williams & O'Reilly, 1998). The information/decision-making perspective on diversity, argues that teams with representatives from different categorical backgrounds potentially have access to a broader range of relevant knowledge than more homogeneous groups (Williams & O'Reilly, 1998). Diverse teams are therefore better positioned to analyse the implications of environmental changes as well as develop more innovative responses, consequent to the integration of disparate knowledge (Ancona & Caldwell, 1992b; Bantel & Jackson, 1989; DeDreu & West, 2001). The alternative, social identity, perspective on diversity holds that differences and similarities between team members provides a basis for the process of categorising individuals into subgroups, represented on the basis of prototypical attributes that typify one subgroup and differentiate it from others (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Tajfel & Turner, 1986) (Lau & Bruton, 2011). Building on the similarity-attraction paradigm and theory of intergroup bias, the social identity perspective argues that members within a subgroup are likely to share positive relationships characterised by trust and knowledge sharing, while interaction across subgroups is typified by conflict and hostility (Tajfel, 1982; Williams & O'Reilly, 1998). While TMT diversity might enhance capacity to sense opportunities because of increased access to knowledge (Certo et al., 2006), it has been argued that the direct effect of TMT diversity may be mixed because of the potential for costs associated with conflict and associated tendency to withhold information (Williams & O'Reilly, 1998). This situation, in which diversity may potentially generate positive, negative and no effect has been termed a ‘dilemmatic structure’ (Gebert, Boerner, & Kearney, 2006). This ‘dilemmatic structure’ suggests the benefit of examining moderating variables that enhance the likelihood of information sharing and utilisation and minimise the negative impact of diversity. The 6 categorisation elaboration model of diversity (van Knippenberg et al., 2004), which integrates both information/decision-making and social identity perspectives, suggests that the positive effects of diversity are contingent on team processes that engender knowledge elaboration and integration. The following section builds on the categorisation elaboration model of diversity to argue a positive effect of TMT functional diversity, defined as variety in functional composition (Harrison & Klein, 2007), on adaptive capability, and, through this, performance. We argue a moderating role for debate, defined as open discussion of differences related to the team’s work (Simons et al., 1999), in the path between diversity and adaptive capability, and build our rationale for a moderated mediated model. Model Development and Hypotheses The information/decision-making perspective suggests that TMT functional diversity provides access to increased breadth of knowledge and skills, and a wider external network on which team members can draw (Williams & O'Reilly, 1998) as well as cross-fertilisation and the generation of novel connections (Fay, Borrill, Amir, Haward, & West, 2006; Jehn, Northcraft, & Neale, 1999). These knowledge-related advantages facilitate the development of a thorough understanding and assessment of environmental pressure and market opportunity for change, as well as the development of more informed and innovative responses to market opportunities or challenges (Caligiuri, Lazarova, & Zehetbauer, 2004; Punnett & Clemens, 1999). Upper echelons research has consistently posited a connection between TMT compositional diversity, including functional diversity, and the adoption of a more ‘broaderminded’ approach to opportunities and complex problems (Dahlin, Weingart, & Hinds, 2005; Gong, 2006), based on the collective resources of TMT members (Carpenter, Geletkanycz, & Sanders, 2004), and consequent development of a more comprehensive portfolio of responses 7 to environmental pressures (Punnett & Clemens, 1999). By enabling a deep understanding of customers, competitors and technology, a functionally-diverse TMTs wide-ranging information sources allow it to assess its position, determine appropriate strategies and initiate quick responses (Qian, Cao, & Takeuchi, 2013). As well as their own knowledge assets, functionally-diverse TMTs have access to more extensive external network ties (Ancona & Caldwell, 1992a; Lee & Park, 2006). These ties represent a rich source of information, which further increases the depth and breadth of knowledge available to inform decisions and facilitate the development and evaluation of alternative solutions (Finkelstein & Hambrick, 1996; Naranjo-Gil et al., 2008). This capacity to identify and acquire external knowledge and to analyse and interpret externally-sourced information from a diversity of perspectives (Dahlin et al., 2005), provides greater opportunity to identify pressures towards change in the external environment, as well as opportunities (Murray, 1989). When environmental conditions change rapidly, their external information network allows diverse TMTs to recognise these changes quickly and make speedy, well-informed decisions regarding appropriate responses. While TMT functional diversity has not been empirically linked to adaptive capability, a number of studies directly or indirectly link TMT composition to organisational change (Bantel & Jackson, 1989; Boeker, 1997). In summary, findings of extant studies support a connection between TMT functional heterogeneity and adaptive capability and lead to the following propositions: Hypothesis 1: Top management team functional diversity is positively related to adaptive capability. Despite these advantages, the benefits that accompany functional diversity are predicted to occur with significant costs. Social categorization and social identification theory, along with the similarity-attraction paradigm, point to an increase in friction, information8 withholding conflict when in-group diversity increases. This effect can suppress the knowledge-related effects that we have argued are likely to enhance adaptive capability (Pietro, Shyavitz, Smith, & Auerbach, 2000). The inclusion of moderator variables in the categorisation-elaboration model (CEM) of diversity effects suggests that elaborative processes may enhance the knowledge-related benefits of diversity and lessen some of the negative impact of social categorisation in diverse teams (van Knippenberg et al., 2004). Functional diversity leads to the availability of different perspectives, however, it is only when team processes facilitate the expression and critical consideration of these perspectives, that the group is able to generate innovative solutions (van Knippenberg et al., 2004). Debate processes have been found to result in the consideration of more alternatives and the more careful consideration of alternatives, to foster a deeper understanding of task issues and to facilitate exchange of information that enhances problem solving, decision making and the generation of ideas (Eisenhardt, Kahwajy, & Bourgeois, 1997; Okhuysen & Eisenhardt, 2002; Pelled, Eisenhardt, & Xin, 1999). In addition, there is evidence that debate of member perspectives and the consequent development of alternative problem solutions prevents premature consensus by limiting the development of confirmatory informationseeking biases (Schweiger, Sandberg, & Rechner, 1989). Debate about assumptions, data and recommendations and prevents uncritical acceptance of what initially appears obvious to members (Schweiger et al., 1989) and also leads to the development of enhanced understanding and clarity regarding causal connections and successful actions (Jehn, 1995, 1997). Such processes increase understanding of others’ positions and have been found to reduce the likelihood that group members’ existing preferences, such as those deriving from stereotypes, will bias the information they choose to retrieve, present, utilise and absorb (Huber & Lewis, 2010). 9 Based on these arguments, we posit that the effect of TMT functional diversity on adaptive capability will be positive as debate increases. The rationale for this positive interaction between TMT diversity and debate rests on our argument that greater debate can diminish the costs while heightening the benefits associated with diversity. It does this by facilitating the expression and critical consideration of disparate perspectives and also limiting the likelihood of information-withholding and bias in decision-making. This also implies that TMT diversity on its own is less likely to exert a positive effect on adaptive capability. In the absence of debate, due to the opposing benefits and costs associated with diversity, we expect the relationship between TMT diversity and adaptive capability to be inconclusive. Only when debate suppresses the costs and strengthens the benefits associated with diversity will a positive relationship emerge. Accordingly, we propose the following contingency hypothesis: Hypothesis 2: TMT debate will moderate the relationship between functional diversity and adaptive capability. This relationship will be such that greater debate will be associated with a stronger positive relationship between diversity and adaptive capability. The ability to effectively adapt to external changes is argued to allow organisations obtain competitive advantage through a series of short-term gains (D'Aveni, 1994). While there is potential for some organisations to achieve competitive advantage by developing certain firm-specific competencies, the dynamism that typifies contemporary markets means that such advantage is often short lived and continuing on the same path of development may not provide further gains (Leonard-Barton, 1992). Environments characterised by changes in demand and technological shifts require the capacity to continuously reshape, and respond faster and more creatively to external challenges (Lavie, 2006). An organisation that is able to understand and predict environmental changes, make well-informed and timely decision, and 10 rapidly implement changes to its processes and structure has the potential to gain and regain competitive advantage (Li, Chen, Liu, & Peng, 2012). The capacity to adapt their original strategies and patterns of activity allows organisations to grasp opportunities more quickly than competitor firms and overcome obstacles and avoid threats (Newey & Zahra, 2009).While other researchers, such as McKee, Varadarajan, and Pride (1989) have suggested that adaptability requires resource utilization and potentially leading to some loss of internal efficiency, the capacity to pursue market opportunity and respond more quickly than competitors has been linked to enhanced firm performance (Oktemgil & Greenley, 1997; Tuominen, Rajala, & Möller, 2004; Wang & Ahmed, 2007) Hypothesis 3: Adaptive capability is positively related to performance. We have argued a path from TMT functional diversity to adaptive capability, moderated by debate, and from adaptive capability to performance. In combination, this suggests a moderated mediated path from TMT diversity to performance: Hypothesis 4: Debate will moderate the relationship between TMT functional diversity and performance. This relationship will be such that the positive relationship between TMT functional diversity and performance through adaptive capability will be stronger at higher levels of debate. METHODOLOGY Sample and data collection Data was collected from organisations that were multinational subsidiaries in Shandong, China in 2010. This sample allowed us to access subsidiary TMTs, which have been relatively neglected in studies of top management and which are faced with multiple demands of parent and host country in a relatively dynamic environment (Gong, 2006). We first sent letters to the CEOs of these subsidiaries, explaining the study’s purpose and inviting 11 participation. Of the 250 subsidiaries invited to participate we received completed questionnaires from 107, representing a 43% response rate. The data was collected through two questionnaires, one to collect dependent variable data and one to collect independent variable data, administered on-site due to advantages documented over mail surveys in China (Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, & Wright, 2000). Site visits ensured that we gained access to the right respondents, in this case the subsidiary Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and Chief Financial Officer (CFO). Language is a significant concern when using constructs developed in one country to collect data in another country (Tsui, Nifadkar, & Ou, 2007). All items were translated from English into the language of participants in China, using the application mode of translation (Van de Vijver & Leung, 1997). With this method, it is assumed that the construct operationalization is appropriate for the national group under investigation and that a straightforward translation will suffice to derive a valid measure. The questionnaires were initially developed in English and then translated into Chinese by two management academics competent in both English and Chinese. The questionnaire was then backtranslated to English and reviewed by two different academics who focused on detecting discrepancies between the translations and attempting to identify potential areas of misunderstanding. Several of our variables, including team diversity, dynamism, munificence and comparative performance had been utilised in previous organizational research in China indicating that the measures used had cross-cultural validity (Atuahene-Gima & Li, 2004; Auh & Menguc, 2006). Two questionnaires were used to collect data. One questionnaire collected data on the independent variables and the other questionnaire collected data on the dependent variable, organizational performance. This approach lessened the risk of bias associated with collecting data on independent and dependent variables from the same source (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, 12 Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). In common with previous research, we sourced predictor variable data from the CEO (Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Simsek, 2007). Prior research has found that CEOs provide data that is as reliable and valid as those from objective data sources (Heavey, Simsek, Roche, & Kelly, 2009). Our performance data was sourced from a separate survey sent to the CFO in each firm. Our sample of firms reported a mean annual turnover of 255 RMB/million ranging from 1 RMB/million to 6480 RMB/million, and employed as average of 8,300 employees. All subsidiaries were located in Shandong. Parent companies were globally dispersed with 55% located in the Asia Pacific region. The remaining parent organisations were located in U.S., Europe, Canada and India. Subsidiaries were established in China between 1996 and 2006, with approximately 70% commencing operations since 2000. Eighty-six percent of subsidiaries were involved in manufacturing with the other subsidiaries involved in assembly, logistics, sales and R&D. The majority (95%) of our STMTs had less than six members with a mean size of 4 members. The mean age of members was 44 years and the average time working as part of the subsidiary TMT was just over 7 years. Measurement: Predictor Variables. Functional Diversity: TMT functional diversity was measured using Blau’s (1977) index of heterogeneity: (1-ΣPi2), where Pi is the proportion of top managers in ith category. Blau’s (1977) index has widespread usage as a measure of group diversity, including functional and national diversity (Harrison & Klein, 2007). A higher score on Blau’s index indicates greater functional diversity. Teams reported nine distinct functional backgrounds with marketing the most frequent. Debate: Debate was measured using a scale from Simons et al (1999). A sample item from this scale is ‘To what extent did the group constructively challenge the suggestions and proposals of members?” The alpha coefficient for this measure was .92. Adaptive Capability: This study uses the four item scale 13 developed by Zhou and Li (2010) based on the conceptual work of Chakravarthy (1982), Lavie (2006), and Mckee et al. (1989). The first item focuses on organisational capacity to undertake appropriate actions in response to environmental shifts, a key characteristic of adaptive capability (Chakravarthy,1982; Mckee et al.,1989). The second item gauges the organisation’s capacity to maintain their competitive advantages in the face of significant industry changes by reconfiguring their existing capabilities (Lavie, 2006). The final two items assess adaptive capability in terms of the organisation’s capacity to effectively deal with challenges arising within the Chinese market, such as its entry into the World Trade Organization. This measure has been verified by Zhou and Li (2010). A sample scale item is “Our existing competencies can withstand changes in the industry”. The alpha coefficient for this measure was .92. Dependent Variable. Performance: Performance was measured using a scale developed to capture a firm’s relative performance (Tan & Litschert, 1994). The items asked the Chief Financial Officer to gauge their performance relative to close competitors. A 5point Likert scale was employed to assess performance, with each scale division representing a 20% increment in comparative advantage. Following Tan and Litschert (1994), we chose this comparative approach because comparative performance data is provided to firms in China on an annual basis by the Chinese government. This approach to has been used to effectively capture performance in western (Pertusa-Ortega, Molina-Azorín, & ClaverCortés, 2009; Smith, Guthrie, & Chen, 1989) and eastern contexts. We used an additive approach to create a 15-point performance measure, combining all three items. Control variables: Firm size was controlled for by including the square root of the number of employees (Powell & Stark, 2005). Past performance has been found to impact future organisational performance (Guthrie & Datta, 2008), and was controlled for by including a measure of comparative subsidiary performance in 2007 (Tan & Litschert, 1994). TMT 14 national diversity was measured using Blau’s (1977) index of heterogeneity: (1-ΣPi2), where Pi is the proportion of top managers in ith category. We also controlled for competitor environmental volatility, as this has been shown to effect subsidiary performance, using a 3item measure developed from existing scales (Calantone, Garcia, & Dröge, 2003; McCarthy, Lawrence, Wixted, & Gordon, 2010). A sample item from this scale is “In our industry, competition changes in major and unpredictable ways as opposed to slowly evolving”. The alpha coefficient for this measure was .86. Finally, we controlled for environmental munificence by asking CEO to assess the extent to which firms in their industry experienced profitability. Analysis and Results This study employed ordinary least squares (OLS) multiple regression analysis and partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modelling (SEM) to analyse data. PLS SEM is a second generation modelling technique is increasingly utilised in organisational studies research (Chen, Lam, & Zhong, 2007), and was used to evaluate our full model. We used SmartPLS version 2.0 software to undertake this analysis (Ringle, Wende, & Will, 2005). Many published studies in management research utilise PLS including, for example, research in group dynamics (Peng & Luo, 2000; Shanxing, Kai, & Jianjun, 2008); strategic management (Julie Juan, 2005), and innovation (Peng, 2001). Of particular relevance for this study, PLS SEM can be used effectively in the initial stages of theory development and provides an overall indication of the predictive utility of models under investigation (Chen et al., 2007). Table 1 shows the means, standards deviations for each variable, and correlations among variables. Prior to investigating our hypotheses, we generated factor loadings to investigate the validity of our measures. Table 2 provides the factor coefficients for each of the study constructs. 15 Insert Table 1 and 2 about Here Inspection of the data in Table 2 reveals that all coefficients are greater than .7. All scale items display the highest coefficients with their parent scale. This support claims of discriminant validity as it indicates conceptual homogeneity within scales and heterogeneity between scales (Thompson, 1997). Ordinary Least Squares regression analysis was employed to investigate our hypotheses as summarised in Table 3. The regression analysis revealed a significant positive path coefficient for the impact of functional diversity on adaptive capability (β=.09, t=1.19, p=.24) providing no support for hypothesis 1. Insert Table 3 about Here To test hypotheses 2, a standardised cross-product interaction construct was computed and included in the model (Allison, 1977). The analysis revealed a significant path coefficient for the interaction variable regressed on adaptive capability (β=.16, t=2.03, p=.04). The results show that debate moderated the impact of TMT functional diversity on adaptive capability as predicted. In order to explore the nature of the moderating effect further, we used simple slopes computations and graphed the interactions using high (1SD above the mean) and low (1SD below the mean) levels of the moderator. These analyses revealed that functional diversity was significantly and positively associated with adaptive capability when debate was high (simple slope=.99, t=2.43, p=.02) and was negatively, but not significantly, related to performance when debate was at a low level (simple slope=-.27, t=-.59, p=.55), as depicted in Figure 1. These results provide support for hypothesis 2 by indicating that functional diversity is linked to adaptive capability when debate is high and not related to adaptive 16 capability when debate is at a low level. Analysis showed a path coefficient for adaptive capability regressed on performance that was also significant (β=.34, t=2.98, p=.00) indicating support for hypothesis 3. No evidence was found for a direct relationship between functional diversity and performance (β=.06, t=0.64, p=.52). Hypothesis 4 posited that the indirect effect of TMT functional diversity on performance via adaptive capability depends on TMT debate. To test moderated mediation, the data was investigated to assess whether the strength of the mediation via adaptive capability differs across levels of the moderator, debate (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). We generated a bootstrap-based bias corrected confidence interval for the specific indirect effect at high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of debate. For low levels of debate, the conditional indirect effect of functional diversity on performance through adaptive capability was not significant (effect = -.16 [95% CI -.87 - .36]). For high levels of debate, the conditional indirect effect of functional diversity was significant (effect = .59 [95% CI .18 -.1.64]), supporting our moderated mediation hypothesis. Insert Figure 1 about Here We used PLS SEM to assess the utility of our full model. While PLS SEM does not generate indicators of model fit, the model r-squared statistic indicates the extent to which hypothesised pathways combine to predict the dependent variable, performance. The rsquared result for the full model, as depicted in Figure 1, was .63, which can be interpreted as indicating good fit (Chin, 1998). In order to further investigate the quality of the structural model, we chose to assess the models capacity to predict adaptive capability and performance. In order to assess predictive relevance, we used PLS SEM to generate the Stone-Geisser criterion (Q2) with an omission distance of 7. Analysis resulted in a Stone–Geisser criterion Q2 value of 0.37 for 17 adaptive capability and 0.42 for performance, which is substantially above the threshold value of zero, and which indicates the model’s predictive relevance (Henseler, Ringle, & Sinkovics, 2009). This supports our claim that functional diversity has a significant impact on adaptive capability and performance, and also supports the utility of the pathways that we have investigated. Discussion The premise of the paper is that explanation for the development of capabilities requires a focus on microfoundations that capture more fully what we know about individual cognition and integrative processes within organizations. Motivated by this premise, we developed a model of the impact of TMT functional diversity on adaptive capability, and through this, organisational performance. In this study we answered the call to discover the role that expertise plays in capabilities (Holcomb et al.2009) by synthesizing insights from dynamic capabilities theory and upper echelons framework to reason that the knowledgerelated advantages bestowed through functional diversity would enhance adaptive capability contingent on debate. Specifically we posited that, while functional diversity potentially increases TMT access to knowledge, elaborative team processes are required to effectively utilise these knowledge assets. We considered that the facilitative role of TMT diversity in enabling greater adaptive capability would be bolstered by debate, which facilitates the expression and critical consideration of their diverse knowledge. Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, support for causality cannot be claimed except through theoretical arguments (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). However, given the theoretical rationale, we interpret the results as providing support for our proposition that functional diversity’s impact on adaptive capability, and through this performance, is not significant unless TMTs engage in debate. Our data support debate as a critical boundary 18 condition of the path from TMT diversity to adaptive capability, and through this performance. This study makes several significant theoretical contributions. First, by identifying functional diversity as an important driver of adaptive capability, this study addresses a significant research gap pertaining to how TMT characteristics potentially contribute to the development of a core dynamic capability (Lavie, 2006). The integration of upper echelons and dynamic capability perspectives illustrates how a TMTs attributes affect its internal resource assortment and reconfiguration. Our findings suggest that, as long as the benefits of functional diversity (greater capacity to identify pressures towards environmental change, ‘broader-minded’ approach to opportunities and complex problems, greater ability to exploit existing competencies) outweigh the potential costs of conflict and information-withholding, functional diversity has a positive and significant impact on adaptive capability. Conversely, when the negative impact of functional diversity overshadows the benefits, diversity does not contribute to adaptive capability. These findings are important because they shed light on the ‘murky waters’ surrounding managerial and cognitive contributors to dynamic capability development (Corbett & Neck, 2010). While considerable progress has been made in understanding the unique role that dynamic capabilities play in competitive advantage, the managerial and cognitive microfoundations of these capabilities have remained relatively underexplored (Helfat 2007). The second contribution of this study entails the investigation of the contingency effect of debate on functional diversity. Our results were supportive of the role debate was predicted to play in explaining the circumstances under which functional diversity generates a positive impact. We found that, as debate increases, the effects of functional diversity on adaptive capability were positive and significant. This suggests that TMT functional diversity drove the development of adaptive capability only under situations where team members 19 engaged in debate. Our simple slope analysis supported this finding; the effect of TMT functional diversity on adaptive capability increased as debate increased. We interpret this finding as indicating that when TMTs are functionally-diverse, while they may have sufficient knowledge assets to engender a more ‘broader-minded’ approach to opportunities and complex problems, without team dynamics that facilitate elaboration and critical assessment, these knowledge-related benefits are unlikely to be sufficient to outweigh the costs associated with dissimilarity. When teams engage in debate, the benefits of diversity are strengthened and the conflict and tension associated with dissimilarity are minimised. Under these circumstances, diversity is linked to the development of adaptive capability. Therefore, to succeed in dynamic environments, organisations should ensure that their TMT membership is sufficiently diverse and also engages in debate. This leads to the speedy initiation of actions in response to environmental change. Our findings have important implications for practitioners. We demonstrate the utility of adaptive capability for subsidiary firms operating in China, a dynamic market context. As a subsidiary’s TMT composition and the processes it uses to make decisions are both associated with adaptive capability, managers should pay attention to ensuring that members from a range of functional backgrounds are not only represented on the TMT but are encouraged to challenge other’s perspective and raise arguments against preferred positions. Interventions such as Devil’s Advocacy and the introduction of openminded norms have been demonstrated to increase the likelihood of such debate (Eisenhardt, Kahwajy, & Bourgeois, 1998). As with all research, this study has a number of limitations. The sample size was relatively small and moderated relationships were investigated, both of which may have increased the risk that significant relationships were not identified (Ren, Kraut, & Kiesler, 2007). However, our hypotheses were supported, and given that the ability to detect 20 moderating variables is particularly constrained by small sample size (Dahl & Pedersen, 2004), we have additional confidence in the robustness of our findings. Another potential limitation of our research stemmed from our use of survey questionnaires. Two different questionnaires were administered separately and to different actors to collect information on dependent and predictor variables. The data on dependent variables was collected from CFOs and the data on predictor variables, including moderator variables, was collected from CEOs, following previous research in strategic management fields which has relied mostly on senior executives as the most knowledgeable respondents (e.g., Heavey et al., 2009). This approach to data collection is in alignment with recommendations by Podsakoff et al (2003) and provides some basis to argue that the risk of common method bias in our data is not significant. However, we recognise that multiple TMT respondents would have enhanced our research design and recommend that future studies in this area utilise such an approach. While our research argued and supported the moderating role of debate, previous studies have suggested that debate could operate as a mediating variable in teams in which intergroup bias is low (Noordegraaf, 2011). We did not find evidence of a direct effect between diversity and debate, however future research on other job-related or biodemographic diversity domains may support a model of sequential mediation between diversity and performance. In conclusion, previous research in the area of dynamic capabilities has been largely conceptual and this study represents one of few to incorporate empirical investigation. In addition, very few past studies have focused on the microfoundations that lead to the development of dynamic capability and even fewer have done so using a quantitative approach. In this study we use unique data from a sample of subsidiaries to investigate the effect of TMT composition that facilitate the capacity assess environmental events, determine appropriate strategies and initiate quick responses and subsequently build adaptive capability, 21 a key dynamic capability. This relationship was contingent on team debate, and together team diversity and debate are the foundation for adaptive capability and through this performance. Our results also support early arguments that, in dynamic environments, performance differences may reflect differences in their capabilities in responding quickly to change (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Helfat et al., 2007; Teece & Pisano, 1997; Zollo & Winter, 2002). 22 Abell, P., Felin, T., & Foss, N. (2008). Building micro‐foundations for the routines, capabilities, and performance links. Managerial and Decision Economics, 29(6), 489-502. Adner, R., & Helfat, C. E. (2003). Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 1011-1025. Allison, P. D. (1977). Testing for interaction in multiple regression. American Journal of Sociology, 144-153. Ancona, D. G., & Caldwell, D. F. (1992a). Bridging the Boundary: External Activity and Performance in Organizational Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(4), 634-661. Ancona, D. G., & Caldwell, D. F. (1992b). Demography and Design: Predictors of new Product Team Performance. Organization Science, 3(3), 321-341. Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20-39. Atuahene-Gima, K., & Li, H. (2004). Strategic decision comprehensiveness and new product development outcomes in new technology ventures. The Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 583-597. Augier, M., & Teece, D. J. (2009). Dynamic capabilities and the role of managers in business strategy and economic performance. Organization Science, 20(2), 410-421. Auh, S., & Menguc, B. (2006). Diversity at the executive suite: A resource-based approach to the customer orientation–organizational performance relationship. Journal of Business Research, 59(5), 564-572. Bantel, K. A., & Jackson, S. E. (1989). Top Management and Innovations in Banking: Does the Composition of the Top Team Make a Difference? Strategic Management Journal, 10(Special Issue: Strategic Leaders and Leadership), 107-124. Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. Barringer, B. R., & Bluedorn, A. C. (1999). The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 421-444. Baum, J., & Wally, S. (2003). Strategic decision speed and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 24(11), 1107-1129. Blau, P. M. (1977). Inequality and heterogeneity : a primitive theory of social structure. New York: Free Press. Boeker, W. (1997). Strategic change: The influence of managerial characteristics and organizational growth. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 152-170. Buyl, T., Boone, C., & Matthyssens, P. (2011). Upper echelons research and managerial cognition. Strategic Organization, 9(3), 240-246. Calantone, R., Garcia, R., & Dröge, C. (2003). The effects of environmental turbulence on new product development strategy planning. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 20(2), 90-103. Caligiuri, P., Lazarova, M., & Zehetbauer, S. (2004). Top managers' national diversity and boundary spanning: Attitudinal indicators of a firm's internationalization. Journal of Management Development, 23(9), 848-859. Carpenter, M. A., & Fredrickson, J. W. (2001). Top management teams, global strategic posture, and the moderating role of uncertainty. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 533-545. Carpenter, M. A., Geletkanycz, M. A., & Sanders, W. G. (2004). Upper echelon research revisitied: Antecedents, elements, and consequences of top management team composition. Journal of Management, 30(6), 749-778. Carpenter, M. A., Sanders, W. G., & Gregersen, H. B. (2001). Building human capital with organisational context: The impact of international assignment experience on multinational firm performance and CEO pay. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 493-511. 23 Certo, S. T., Lester, R. H., Dalton, C. M., & Dalton, D. R. (2006). Top Management Teams, Strategy and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analytic Examination. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 813-839. Chen, Z., Lam, W., & Zhong, J. A. (2007). Leader-member exchange and member performance: a new look at individual-level negative feedback-seeking behavior and team-level empowerment climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 202-212. Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, vii-xvi. D'Aveni, R. A. (1994). Hypercompetition: Managing the dynamics of strategic maneuvering. New York, NY: Free Press. Dahl, M. S., & Pedersen, C. Ø. (2004). Knowledge flows through informal contacts in industrial clusters: myth or reality? Research Policy, 33(10), 1673-1686. Dahlin, K. B., Weingart, L. R., & Hinds, P. J. (2005). Team diversity and information use Academy of Management Journal (Vol. 48, pp. 1107-1123). DeDreu, C., & West, M. (2001). Minority dissent and team innovation:The importance of participation in decision-making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1191-1201. Eisenhardt, K., Kahwajy, J., & Bourgeois, L. J., III. (1998). Taming Interpersonal Conflict in Strategic Choice: How Top Management Teams Argue, but Still Get Along. In V. Papadakis & P. Barwise (Eds.), Strategic Decisions (pp. 65-83). New York: Springer. Eisenhardt, K. M., Kahwajy, J. L., & Bourgeois, L. J., III. (1997). Conflict and strategic choice: How top managemen teams disagree. California Management Review, 39(2), 42-61. Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10/11), 1105. Fay, D., Borrill, C., Amir, Z., Haward, R., & West, M. (2006). Getting the most out of multidisciplinary teams: A multi-sample study of team innovation in heatlh care. Journal of Occupation and Organizational Psychology, 79(4), 553-567. Felin, T., & Foss, N. (2006). Individuals and organizations: thoughts on a micro-foundations project for strategic management and organizational analysis (Vol. 3): Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Felin, T., & Foss, N. J. (2005). Strategic organization: A field in search of micro-foundations. Strategic Organization, 3(4), 441-455. Felin, T., & Foss, N. J. (2009). Organizational routines and capabilities: Historical drift and a coursecorrection toward microfoundations. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(2), 157-167. Felin, T., Foss, N. J., Heimeriks, K. H., & Madsen, T. L. (2012). Microfoundations of routines and capabilities: Individuals, processes, and structure. Journal of Management Studies, 49(8), 1351-1374. Felin, T., & Hesterly, W. S. (2007). The knowledge-based view, nested heterogeneity, and new value creation: Philosophical considerations on the locus of knowledge. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 195-218. Finkelstein, & Hambrick, D. C. (1996). Strategic Leadership: Top executives and their effects on organizations. St Paul, MN: West. Foss, N. J. (2011). Invited editorial: Why micro-foundations for resource-based theory Are needed and what they may look like. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1413-1428. Frazier, P., Tix, A., & Barron, K. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counselling psychology research. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 51(1), 115-134. Gavetti, G. (2005). Cognition and hierarchy: Rethinking the microfoundations of capabilities’ development. Organization Science, 16(6), 599-617. Gebert, D., Boerner, S., & Kearney, E. (2006). Cross-functionality and innovation in new product development teams: A dilemmatic structure and its consequences for the management of diversity. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 15(4), 431-458. Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209-226. 24 Gong, Y. (2006). The impact of subsidiary top management team national diversity on subsidiary performance: Knowledge and legitimacy perspectives. Management International Review, 46(6), 771-789. Griffith, D. A., & Harvey, M. G. (2001). A resource perspective of global dynamic capabilities. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3), 597-606. Guthrie, J. P., & Datta, D. K. (2008). Dumb and dumber: The impact of downsizing on firm performance as moderated by industry conditions. Organization Science, 19(1), 108-123. Hambrick, D. C. (2007). Upper echelons theory: An update. The Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 334-343. Hambrick, D. C., Cho, T. S., & Chen, M.-J. (1996). The influence of top management team heterogeneity on firms' competitive moves. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(4), 659-684. Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193. Harrison, D. A., & Klein, K. J. (2007). What's the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1199-1228. Heavey, C., Simsek, Z., Roche, F., & Kelly, A. (2009). Decision comprehensiveness and corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating role of managerial uncertainty preferences and environmental dynamism. Journal of Management Studies, 46(8), 1291-1314. Helfat, C., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D., & Winter, S. (2007). Dynamic Capabilities. Understanding Dynamic Change in Organizations. Oxford: Blackwell. Helfat, C. E., & Winter, S. G. (2011). Untangling Dynamic and Operational Capabilities: Strategy for the (N) ever‐Changing World. Strategic Management Journal, 32(11), 1243-1250. Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in international marketing, 20, 277-319. Hitt, A., Bierman, L. S., Shimizu, K., & Kochhar, R. (2000). Direct and Moderating Effects Of Human Capital On Strategy and Performance In Professional Service Firms: A ResourceBased Perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 13-29. Hoopes, D. G., & Madsen, T. L. (2008). A capability-based view of competitive heterogeneity. Industrial and Corporate Change, 17(3), 393-426. Hoskisson, R., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wright, M. (2000). Strategy in Emerging Economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249-267. Huber, G. P., & Lewis, K. (2010). Cross-understanding: Implications for group cognition and performance. Academy of Management Review, 35(1), 6-26. Jehn, K., Northcraft, G. B., & Neale, M. (1999). Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict and performance in work groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 741-763. Jehn, K. A. (1995). A Multimethod Examination of the Benefits and Detriments of Intragroup Conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(June), 256–282. Jehn, K. A. (1997). Qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions in organizational groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(3), 530-557. Julie Juan, L. (2005). The Formation of Managerial Networks of Foreign Firms in China: The Effects of Strategic Orientations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 22(4), 423-443. Kor, Y. Y., & Mesko, A. (2013). Dynamic managerial capabilities: Configuration and orchestration of top executives' capabilities and the firm's dominant logic. Strategic Management Journal, 34(2), 233-244. Lau, C. M., & Bruton, G. D. (2011). Strategic orientations and strategies of high technology ventures in two transition economies. Journal of World Business, 46(3), 371-380. Lavie, D. (2006). The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resourcebased view. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 638-658. Lee, H. U., & Park, J. H. (2006). Top Team Diversity, Internationalization and the Mediating Effect of International Alliances. British Journal of Management, 17(3), 195-213. 25 Leonard-Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 13(Summer special issue), 111-125. Li, Y., Chen, H., Liu, Y., & Peng, M. W. (2012). Managerial ties, organizational learning, and opportunity capture: A social capital perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1-21. Ma, X., Yao, X., & Xi, Y. (2009). How do interorganizational and interpersonal networks affect a firm's strategic adaptive capability in a transition economy? Journal of Business Research, 62(11), 1087-1095. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.09.008 McCarthy, I. P., Lawrence, T. B., Wixted, B., & Gordon, B. R. (2010). A multidimensional conceptualization of environmental velocity. Academy of Management Review, 35(4), 604626. McKee, D. O., Varadarajan, P. R., & Pride, W. M. (1989). Strategic adaptability and firm performance: a market-contingent perspective. The Journal of Marketing, 53(3), 21-35. Murray, A. I. (1989). Top management group heterogeneity and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 10(S1), 125-141. Naranjo-Gil, D., Hartmann, F., & Maas, V. S. (2008). Top Management Team Heterogeneity, Strategic Change and Operational Performance. British Journal of Management, 19(3), 222234. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00545.x Newey, L. R., & Zahra, S. A. (2009). The evolving firm: how dynamic and operating capabilities interact to enable entrepreneurship. British Journal of Management, 20(s1), S81-S100. Noordegraaf, M. (2011). Risky Business: How professionals and professional fields (must) deal with organizational issues. Organization Studies, 32(10), 1349-1371. Okhuysen, G. A., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2002). Integrating knowledge in groups: How formal interventions enable flexibility. Organization Science, 13(4), 370-386. Oktemgil, M., & Greenley, G. (1997). Consequences of high and low adaptive capability in UK companies. European Journal of Marketing, 31(7), 445-466. Pelled, L. H., Eisenhardt, K. M., & Xin, K. R. (1999). Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict, and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 1-28. Peng, M. W. (2001). Business Strategies in Transition Economies. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 311-313. Peng, M. W., & Luo, Y. (2000). Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 486-501. Pertusa-Ortega, E. M., Molina-Azorín, J. F., & Claver-Cortés, E. (2009). Competitive Strategies and Firm Performance: a Comparative Analysis of Pure, Hybrid and ‘Stuck-in-themiddle’Strategies in Spanish Firms. British Journal of Management, 20(4), 508-523. Pietro, D., Shyavitz, L., Smith, R., & Auerbach, B. (2000). Detecting and reporting medical errors: Why the dilemma? British Medical Journal, 320, 794-796. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903. Powell, R. G., & Stark, A. W. (2005). Does operating performance incrase post-takeover for UK takeovers? A comparison of performance measures and benchmarks. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11, 293-317. Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate behavioral research, 42(1), 185-227. Punnett, B. J., & Clemens, J. (1999). Cross-national diversity: implications for international expansion decisions. Journal of World Business, 34(2), 128-138. Qian, C., Cao, Q., & Takeuchi, R. (2013). Top management team functional diversity and organizational innovation in China: The moderating effects of environment. Strategic Management Journal, 34, 110-120. Ren, Y., Kraut, R., & Kiesler, S. (2007). Applying common identity and bond theory to design of online communities. Organization Studies, 28(3), 377-408. 26 Ringle, C., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2005). SmartPLS version 2.0 M2: Hamburg,, Germany: Institute for Operations Management and Organization at the University of Hamburg. Schweiger, D., Sandberg, W., & Rechner, P. (1989). Experiential effects of dialectical inquiry, devil's advocacy, and consensus approaches to strategic decision making. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 745-772. Shanxing, G., Kai, X., & Jianjun, Y. (2008). Managerial ties, absorptive capacity, and innovation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(3), 395-412. Simons, T., Pelled, L. H., & Smith, K. A. (1999). Making Use of Difference: Diversity, Debate, and Decision Comprehensiveness in Top Management Teams. Academy of Management Journal, 42(6), 662. Simsek, Z. (2007). CEO tenure and organizational performance: An intervening model. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 653-662. Sirmon, D. G., & Hitt, M. A. (2003). Managing resources: Linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(4), 339-358. Smith, K. G., Guthrie, J. P., & Chen, M. J. (1989). Strategy, size and performance. Organization Studies, 10(1), 63-81. Smith, K. G., Smith, K. A., Olian, J. D., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (1994). Top management team demography and process. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(3), 412-438. Staber, U., & Sydow, J. (2002). Organizational Adaptive Capacity A Structuration Perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry, 11(4), 408-424. Tajfel, H. (1982). Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup conflict. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7-24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall. Tan, J. J., & Litschert, R. J. (1994). Environment-strategy relationship and its performance implications: An empirical study of the Chinese electronics industry. Strategic Management Journal, 15(1), 1-20. Teece, D., & Pisano, G. (1998). The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. In G. Dosi, D. Teece & J. Chytry (Eds.), Technology, organization and competitiveness: Perspectives on industrial and corporate change (pp. 17-66). New York: Oxford University Press. Teece, D., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533. Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319-1350. Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509. Thompson, B. (1997). The importance of structure coefficients in structural equation modeling confirmatory factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57(2), 5-19. Tripsas, M., & Gavetti, G. (2000). Capabilities, Cognition, and Inertia: Evidence from Digital Imaging. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10/11), 1147. Tsui, A. S., Nifadkar, S. S., & Ou, A. Y. (2007). Cross-national, cross-cultural organizational behavior research: Advances, gaps, and recommendations. Journal of Management, 33(3), 426-478. Tuominen, M., Rajala, A., & Möller, K. (2004). How does adaptability drive firm innovativeness? Journal of Business Research, 57(5), 495-506. Van de Vijver, F. J., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research (Vol. 1). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. van Knippenberg, D., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Homan, A. C. (2004). Work Group Diversity and Group Performance: An Integrative Model and Research Agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 1008-1022. Wang, C. L., & Ahmed, P. K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 9(1), 31-51. 27 Williams, K. Y., & O'Reilly, C. A., III. (1998). Demography and Diversity in Organizations: A Review of 40 Years of Research. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 20, pp. 77-140). London: JAI Press Inc. Zhou, K. Z., & Li, C. B. (2010). How strategic orientations influence the building of dynamic capability in emerging economies. Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 224-231. Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate Learning and the Evolution of Dynamic Capabilities. Organization Science, 13(3), 339. 28 TABLE 1 Variable Means, Standard Deviations and Correlation Coefficients Mean SD 1 Munificence 3.21 2 Dynamism 3.31 .98 3 Size 48.26 79.09 4 Past Performance 5 National Diversity 6 Functional Diversity 7 3.6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1.2 .49** .13 -.08 .71 .35** .20* .07 .20 .22 .02 -.02 -.11 .21 .22 -.05 -.04 .02 Debate 3.85 .76 .18 .14 -.05 .37** -.06 -.13 8 Adaptive Capability 3.71 .90 .62** .39** .16 .28** .02 .06 9 Performance 7.03 1.72 .43** .23** .16 .05 -.1 .32** .12 -.10 .04 .25* .19 .48** *p<.05 **p<.01 29 TABLE 2 Latent Variable Factor Loadings Dynamism Debate Adaptive Comparative Capability Performance Dynamism 1 .88 .09 .13 .13 Dynamism 2 .88 -.09 .12 .16 Dynamism 3 .87 .19 .29 .04 Debate 1 .09 .91 .06 .00 Debate 2 .07 .94 .13 .08 Debate 3 .02 .90 .15 .13 Adaptive Capability 1 .13 .15 .82 .08 Adaptive Capability 2 .12 .11 .88 .09 Adaptive Capability 3 .16 .08 .88 .19 Adaptive Capability 4 .22 .08 .86 .28 Performance 1 .14 .12 .08 .91 Performance 2 .11 .17 .21 .86 Performance 3 .07 -.06 .19 .79 30 TABLE 3 Model of Moderating Role of Debate on the Relationship between TMT Functional Diversity, Adaptive Capability and Organizational Performance (N = 107) Dependent Variable Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Adaptive Adaptive Performance Capability Capability Munificence .53** .53** Dynamism .12 .14 -.02 Size .11 .11 .06 Past Performance .01 -.01 .18 National Diversity .02 .01 -.11 Functional Diversity .11 .09 .06 Debate .16 .12 .05 .16* -.12 Functional Diversity X Debate Adaptive Capability Adjusted R2 R2 ∆ a .15 .34** .40 .42 .25 .02* .06** Beta weights are shown. *p<.05; **p<.01 31 FIGURE 2 Moderating Effect of Debate on Functional Diversity’s Impact on Adaptive Capability 32 2.5 Adaptive Capability 2 1.5 High Debate 1 Low Debate 0.5 0 Low Diversity High Diversity 33