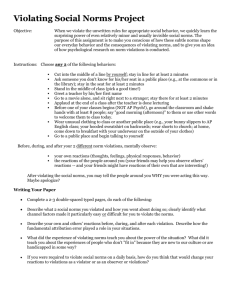

Correcting each other

advertisement

Correcting each other Normativity, agreement and the second person DRAFT Glenda Satne University of Buenos Aires Argentina glendasatne@gmail.com Even if it appears quite evident that we live within society and are bound together by shared institutions and norms, the nature of this relationship is a source of philosophical perplexity. One example of this perplexity is the famous debate on the origin of a political order and binding norms and practices in terms of consent granted by individuals. Contractualists have often argued that what makes a political order legitimate, one in which the norms are binding for the individuals that belong to a community, is their consent – deliberately and consciously – to the law. But to quote a well-known text by Hume,1 this strategy is problematic since We are bound to obey our sovereign, it is said, because we have given a tacit promise to that purpose. But why are we bound to observe our promise? It must here be asserted, that the commerce and intercourse of mankind, which are of such mighty advantage, can have no security where men pay no regard to their engagements (…) The obligation to allegiance being of like force and authority with the obligation to fidelity, we gain nothing by resolving the one into the other. The problem at hand goes beyond the source of the normative binding force of the authority granted to the sovereign. Although that question is a critical one here, Hume’s point is not restricted to contractualism but can be extended to any attempt to account for the normative force of law i.e. the possibility that we are bound together under the same law. This is why we will not solve the problem by appealing to promises since promises are binding in so far as we are obliged to keep them. The same question thus returns: how are we bound within a norm that obliges us to keep our promises? The problem at hand, as Anscombe has pointed out, concerns the very possibility of rules, rights and promises.2 What they have in common is the fact that they involve, first, a normative component, in the sense that they generate an obligation in terms of 1 2 Hume, D. (1748) “Of the original contract.” Anscombe, “Rules, Rights and Promises.” 1 which actions can be assessed as correct or incorrect. Second, they presuppose the sharing of an act and of its content among those who promise to be faithful to one another or who consent and grant authority to a certain set of rules or rights. This is why the question of normativity leads, in a somewhat direct way, to the problem of agreement. This is clearly seen in Wittgenstein’s considerations regarding rulefollowing and the impossibility of private languages. Wittgenstein’s most well-known argument against the possibility of a private language focuses on how it is impossible for privatist conceptions of meaning to offer an account of normativity. A language—the meaning of which is by definition only accessible to the individual, unknowable by anyone other than she who ‘has’ it 3 — would prove incoherent. In order to account for the capacity to speak and understand a language, no matter how this last notion is to be understood, we need to explain the speaker’s capacity to ‘follow semantic rules’ i.e. the rules that specify the correct application of a term in different situations 4 . If there were no distinction between correct and incorrect applications of a term, then there would be no meaning at all, since the very notion of content would fade away: if anything is correct, nothing is correct (see PI 201 and 258). Accounting for what makes it possible for someone to speak and understand a language requires shedding light on what it means to follow rules and how we are able to do so. This is exactly what the privatist model cannot account for. In such a model, what is correct collapses with what seems correct to the individual and hence makes it impossible to establish any correction criteria for the individual’s behavior: anything that seems correct to the individual would be correct. Accounting for normativity demands accounting at the same time for the possibility of error. In order to do that, contents should be thought as such that binds the individual’s behavior externally, and that means that contents are objective and in principle shareable, as opposed to private. On the other hand, as a number of authors have emphasized5, norms should be self- A private language is a language whose words “are to refer to what can only be known to the person speaking; to his immediate private sensations. So another person cannot understand the language.” (IF243) 4 Wittgenstein’s argument may be better described as raising a problem about the nature of meaning than as concerning our capacity to speak a language. In this formulation, I am following Sellars (“Some reflections on language games”) who presents the problem of the nature of the rules as one that concerns our coming to understand our capacity to follow semantic norms (Cfr. Satne, 2005). 5 Starting with Kant’s conception of self-consciousness as giving form to every rational rule (Anscombe, Rödl). Rödl expresses this requirement in the following way: “The subject has consciousness of itself as following a rule.” 3 2 consciously underwritten by the agent, i.e. something to which the agent gives her consent and not something that anonymously or non-voluntarily obliges her. To account for normativity, then, means responding to the following conditions of adequacy: 1. First-personal character of rule-following. This amounts to accounting for the difference between acting according to the norm and acting in virtue of the norm. Following a norm means that one’s action is internally connected to a norm in the lights of which it is to be assessed: norms are patterns of assessment for one’s own behavior. In this sense, following a rule requires selfconsciousness and thus the subject’s awareness that he is following a rule. 2. Objectivity of norms. What is to be agreed on is what is correct (whereas what is correct is not just correct because it is what is agreed upon)6. In this regard, the norm functions as an external binding on one's behavior. This means that the norms are both external bindings and patterns for the individual to assess her own behavior as well as that of others who are supposed to be bound by the same norm. In this manner, we can see that normativity is intrinsically social, and norms are shared things through which we bind ourselves together to act in specific ways.7 However, once we accept that normativity is intrinsically social, the following question immediately arises: How does social interaction exhibit the normativity of meaning as an external binding and a pattern of assessment for each individual’s behavior? This question is crucial to a proper understanding of normativity and leads us directly to the problem of agreement. The agreement in question is not merely the ability to share reasons that is at issue in the objective condition of adequacy mentioned 6 McDowell (1984) has emphasized the importance of the objectivity requirement, pointing out that what is at risk is our capability to discuss matters as such-and-such independently of what we say about them, and, more importantly, that what is at risk is not merely the factual content of norms but a central trait of normativity i.e. that the norm is an external binding on us and is independent of our opinion. 7 The stopping modals (must, can’t…) are the language through which we come to learn common norms from others who train us in the use of language (See Anscombe…) 3 above (2). Instead, it is the understanding of how and when norms are actually shared by those who bind themselves by them; this is why, as we will see, the agreement in question is an agreement in judgment. Wittgenstein, and others who agreed with him on this point, claimed that agreement was key to understanding rule-following in a non privatist way. When understood in this way, agreement provides the necessary framework to account for rule-following. Thus, by considering different accounts of agreement as a leading thread, we may shed light on the problem of rule-following and provide an answer to SI. In this paper, I will consider Wittgenstein’s own position as well as what I will call the communitarian and the interpretationist ways of understanding agreement that are, at least partially, inspired by it. I will propose a third one, different from both, a secondpersonal conception of it. The paper will thus proceed as follows. First, I will examine the notion of agreement as defined by Wittgenstein. I will then examine the communitarian reading of agreement and the interpretationist one. It will become apparent that the understanding of agreement in such accounts is restricted to the mere similarity of responses or to the attribution of similar propositional attitudes. I will argue that agreement, when understood in this manner, provides a picture of what is involved in rule-following that is inadequate insofar as it cannot satisfy the firstpersonal and the objectivity requirements. I will then put forward a richer notion of agreement that is exhibited in a specific kind of second-personal interaction. Departing from such interaction will allow us to describe the dynamic character of social interaction in terms of mutual recognition. I will argue that being part of a shared space of reasons requires being able to engage in this kind of interaction; this requirement is an a priori condition of possibility of our capacity to share norms. In particular, I will claim that intercorregibility is the basic practice that exhibits the shared character of norms. The very practice of correcting one another and the principles governing it provide a way of overcoming the explanatory insufficiency of the accounts examined and allow us to understand what it is for subjects, i.e. members of a single community, to be bound by the same norms. I. Some reflections on agreement It is well-known that the key notion that Wittgenstein puts forward to replace the usual picture of rule-following as a grasping of private entities is the notion of 4 agreement. It is, as we will show, not an agreement in opinions but an agreement in form of life. When understood in this way, agreement provides the necessary framework to account for rule-following. Wittgenstein says in PI 510: “Make the following experiment: say ‘It’s cold here,’ and mean ‘It’s warm here.’ Can you do it? And what are you doing as you do it? And is there only one way to do it?” The possibility explored here is that of a mind to which the contents were presented as isolated graspable items that required interpretation to bridge the gap between them and their application. Wittgenstein is emphasizing that if this were the case, there would be no way to reach a correct interpretation for any term or rule since, as he points out, “every course of action can be made out to accord with the rule.” That is suggested in the final question of the above quoted passage: “And is there only one way to do it?”. “(I)f everything can be made out to accord with the rule, then it can also be made out to conflict with it. And so there would be neither accord nor conflict here,” (PI 201). Wittgenstein then concludes that following a rule is not a matter of associating an interpretation to a set of words or mental items that would be otherwise inert. On the contrary, what is involved there is “a way of grasping a rule which is not an interpretation, but which is exhibited in what we call ‘obeying the rule’ and ‘going against it’ in actual cases,” (PI 201). Hence, Wittgenstein can claim that agreement plays a crucial role: “The word ‘agreement’ and the word ‘rule’ are related. They are cousins. The phenomena of agreement and of acting according to a rule hang together.”8 Wittgenstein thus remarks that the agreement essential to rule-following should be understood as an agreement in form of life. Against the Augustinian model of 8 Wittgenstein, L. (1956), Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics, Ed. G.H. von Wright, R. Rhees, G.E.M. Anscombe, transl. G.E.M. Anscombe, Blackwell, Oxford, VI, 41. RFM onwards. This notion of agreement is further specified in RFM; VI, 39: It is true that anything can be somehow justified. But the phenomenon of language is based on regularity, on agreement in actions. Here it is of the greatest importance that all or the enormous majority of us agree in certain things. I can, e.g., be quite sure that the color of this object can be called ‘green’ by far the most of the human beings who see it. It would be imaginable that humans of different stocks possessed languages and all had the same vocabulary, but the meaning of the words was different. The word that meant green among one tribe meant same among other, table for a third and so on. We could even imagine that the same sentences were used by the tribes, only with entirely different senses. Now in this case I should not say that they spoke the same language. We say, that in order to communicate, people must agree with one another about the meaning of the words. But the criterion for this agreement is not just agreement with reference to definitions, e.g., ostensive definitions—but also an agreement in judgments. It is essential for communication that we agree in a large number of judgments. 5 language based on understanding words as labels for things, Wittgenstein claims that “to understand a language means having mastered a technique” (PI 199) inserted in a form of life9. It is indeed a social activity inserted in institutions, a habit characterized by the agreement of men when practicing it. This counts as the step towards the community that Wittgenstein claims is what makes the very idea of rule-following intelligible. Wittgenstein provides us with two indications on how to understand the concept of form of life. The first concerns the relationship between form of life and natural history; the second the relation between consensus and agreement in form of life. One way in which agreement can be understood is in the light of the relationship between form of life and natural history. In PI 25, for instance, Wittgenstein says: “Giving orders, asking questions, telling stories, having a chat, are as much part of our natural history as walking, eating, drinking, playing.” Wittgenstein thus indicates that the possibility of rule-following is based on sharing a form of life that is at least partially constituted by our reacting in the same way, as a result of a shared natural or biological history. 10 In this sense, Wittgenstein claims that a form of life involves a shared natural history. Nevertheless, Wittgenstein also argues that the relevant notion of agreement at stake in the elucidation of rule following is not describable in terms of a statement of natural history, even if such history is part of its necessary background: What you say seems to amount to this, that logic belongs to the natural history of man. And that is not combinable with the hardness of the logical “must”. But the logical “must” is a component part of the propositions of logic and these are not propositions of human natural history. If what a propositions of logic said was: Human beings agree with one another in such and such ways (and that would be the form of the natural-historical proposition), then its contradictory would say that there is here a lack of agreement. Not, that there is an agreement of another kind. The agreement of humans that is a presupposition of logic is not an agreement in opinions, much less in opinions on questions of logic. (RFM, VI, 49) 9 See also PI 19, PI 23, and pp. 174 and 226-27. Thompson (2008, p. 79) agrees with this inasmuch as this agreement could not be captured by propositions of natural selection and hypothesis about the past. The proposition that constitutes a natural historical judgment is defined by its peculiar use of the present tense, its teleological form and by its interconnections with other propositions of the same form all of which characterize a system of natural history. It is clear that Wittgenstein in RFM is objecting to an empirical understanding of agreement, including the hypothesis of natural selection. But it is also the case that he is rejecting the understanding of agreement in terms of a mere fact. He is thus pointing towards an understanding of the conditions of possibility of our agreements in judgment and action. 10 6 This passage refers us to the second pair of concepts mentioned above: agreement is not a consensus in opinions; the agreement at stake is prior to the possibility of any opinion. As he says in PI 241: “So you are saying that human agreement decides what is true and what is false? – What is true or false is what human beings say; and it is in their language that human beings agree. This is agreement not in opinions, but rather in form of life.” Wittgenstein thus notes that there is a relationship between natural history and form of life but clarifies that the agreement in form of life does not take—and could not take—the form of an agreement on a proposition; strictly speaking, since such an agreement is presupposed in the very use of language, in every expression of opinion and in the very possibility of conceptual experience, it cannot be expressed in an empirical proposition. Agreement defines the very essence of what following a rule involves; it is what makes conceivable the logical “must” as such and cannot be expressed by a contingent proposition that could be asserted or denied in language. Wittgenstein points out that the relationship between agreement and rulefollowing is grammatical, meaning that agreement defines what following a rule involves (see RFM, VII, 39/40). Agreement cannot be accounted for independently of the very practice of rule-following. In this sense, it cannot be identified with a natural historical judgment if this is understood as the cause of us having shared practices. It is only through the practice of following rules that the agreement Wittgenstein is interested in is exhibited as the condition for the possibility of such practices. From there emerges a methodological principle that grounds SI: in order to account for agreement and the shareability of norms, we need to pay attention to the actual practices where this shareability is exhibited. A central question is then how to understand agreement as constitutive of rulefollowing in a way that does not collapse with the notion of consensus or agreement in opinions. Nor is agreement reduced to a mere natural-historical description of human behavior, even if natural history is a necessary background for it.11 In the next section, I will explore different philosophical descriptions of the notion of agreement in connection with rule-following to point out their limitations. I will then present my own proposal on how to understand agreement in a way that One might think that this challenge finds a counterpart in M. Thompson’s “A Puzzle about Justice.” Even if the Aristotelian case which Thompson seems to be more sympathetic to presents natural-historical judgments in which one tries to describe the agreement that underlies the validity of moral laws, one still has to explain how the content of the concept of the human life form is epistemologically accessible so it may ground a priori norms for each subject. This is why Thompson excludes field work as a way to answer such normative questions. See Thompson, pp. 377-8. 11 7 avoids such difficulties. In this paper, and in following with the authors examined in the next section, I have no intention of providing an exegetical account of Wittgenstein’s position but rather attempt to find inspiration from some of his remarks to provide an appropriate answer to the problem presented here. II. Conceptions of Agreement in Human Interaction A way in which the question of agreement can be addressed is through the distinct understandings of who is the actual subject of agreement. In this regard, there seems to be at least two alternative positions that need to be considered. The first is that which conceives agreement as something that a community does and hence characterizes the community as such. According to this position, it is as a we that we agree with each other and it is through our becoming a we that we can be assured of sharing the same norms. Overcoming the plurality of first-personal perspectives through the constitution of a we is part of the path taken by what I will call the communitarian strategy to respond to SI. The second strategy involves understanding agreement in terms of the way in which each of the subjects examines the behavior of others to see if it agrees with their own, i.e. by being interpreted as agreeing. In that sense, the assessment of the conduct of others from a third personal perspective characterizes agreement. This is what distinguishes what I will refer to as the interpretationist strategy to respond to SI. In this section I will explore the communitarian reading of Wittgenstein’s agreement as exemplified by Kripke’s interpretation of the rule-following paradox, and the interpretationist reading of agreement developed by Davidson and Brandom, as alternatives strategies to respond to SI. Even if all of these authors agree with Wittgenstein’s remarks on the need for understanding interaction in order to comprehend normativity, I will try to show they all fail to provide an adequate account of the kind of interaction that exhibits the agreement that constitutes normativity. Providing such an account requires conceiving of agreement in terms not of a first (we agree) nor of a third personal (you agree with me) perspective but of a second-personal one (you and I agree with each other). This will prove to be the kind of thought that establishes a relationship between the agents in the way required by the SI conditions of adequacy. 8 A. Agreement as Consensus. The Communitarian Approach. Communitarian accounts of rule-following claim that it is a social fact about us that we are subject to the same norms. According to this line of thought, this very fact—that we agree on most of our judgments—can explain the nature of the normativity involved in our common normative practices.12 One account that has been presented as an interpretation of rule-following is Kripke’s reading of Wittgenstein;13 his skeptical solution is paradigmatic of what may be called a consensual understanding of the content of rules.14 According to Kripke, the kind of agreement that is required to account for rule-following can be captured in the following lemma: you should act as the community does. Agreement is understood as how the individual’s responses to a certain event resemble those of most community members. According to this reading, the community accepts a member, i.e. deems that she follows rules in general and a given rule in particular, if she acts in accordance with the way in which the community would act in those circumstances. For Kripke, then, this leads to a reformulation of the conditionals that attribute meaning to a given conduct (for instance, “If she is adding, she would say four as a response of two plus two,”) in terms of its opposite (“If she does not answer four when asked ‘What is two plus two?’ then she is not adding,”). If an individual does not do what is expected of her, the community concludes that she is not following the rule; if the individual passes enough tests successfully, the community would accept her by categorically asserting that she is following the rule (see Kripke, 1982, pp. 91ff.). Kripke characterizes these as conditions of assertability for attributing meaning but not as truth conditions since there are no facts of the matter to which the community is responding. Finally, Kripke argues that such attributions make sense insofar as they “are part of our form of life,”, in his terms, this means that such attributions play a role in the life of the community and are useful within it, allowing hence for predictability and trust in social interaction. As we will see, however, this shift towards the shared nature of rule-following is incorrect, since Kripke’s notion of agreement amounts to a merely external behavioral coincidence. An important feature of rule-following that the notion of agreement is Examples of Communiatrian accounts of normativity are. Rorty’s ethnocentric account of norms. (Rorty (…)) and Charles Taylor (…) and Martha Nussbaum’s (….) conception of moral norms. Hume (…) can also be understood as endorsing this conception of norms. 13 Kripke, Saul (1982), Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language. An Elementary Exposition, Harvard UP, Cambridge. 14 In this section I will not address Kripke’s problematic reading of the Wittgenstein paradox (Cfr. Haddock….) but instead focus on his skeptical solution as an example of the communitarian approach to the nature of rules. 12 9 intended to account for is the idea of “acting in the same way” that seems to be presupposed in the very idea of following a rule. But, as Brandom has pointed out, it is not enough to account for acting in the same way; we additionally need to explain how we know how to go on, i.e. how we know how to continue the series in the same way (for instance, knowing that two must be added to the previous number in order continue the series “2, 4, 6, 8…”). According to Kripke, the norms can be derived from one general rule: “Act as the community does.” If we want to understand what the individual is supposed to know, according to Kripke, we can then assume that in spite of his primitive tendencies to act in a certain way (Kripke, 1982, pp….), each individual must notice if the conduct of someone else is the same as hers, if he carries on as she would. But this would amount only to an external matching of observable behavior— and this is clearly insufficient. First, because, as Brandom has shown, it amounts only to the idea of acting conforming to what one ought to do but not in virtue of what one ought to do.15 That leaves open the possibility of multiple ways in which we can follow the series departing from the behavior the other exhibits and could thus imply that the subject does not really know what to do.16 But, more seriously, it also shows that the subject is acting for the wrong kind of reasons. He is not acting in virtue of what the norm requires of him but merely because this is what other people do. However, this also shows that the individual is not really sensitive to the distinction between what she ought to do and what she is doing because she is free to interpret the conduct of the other as in agreement with hers by merely interpreting her own behavior as responding to a different norm than the one the other person is responding to (say, he is quuing and not adding). This is why this description of what is involved in normativity cannot distinguish between what is correct and what one actually does in a way that allows the former to be a criterion for the assessment of the latter. And thus, this not only shows that the individual cannot be sensitive to the distinction between what she is required to do and what she simply does but also that this view of agreement completely obliterates the objectivity of the norms involved, since in this view individuals do not act in virtue of the norms but instead they merely act: what is correct collapses with what seems correct in the eyes of the community17. 15 See Brandom, R. (1994), Making it Explicit, Harvard UP, Cambridge, Mass, pp. 26ff. Notice that Kripke cannot say that the subject already knows how to interpret the other person’s conduct because that would presuppose that she sees the meaning of this conduct, which is discarded with the acceptance of the skeptical conclusion. See Satne (2005). Goldfarb (1995). 17 See McDowell, J. (1984), “Wittgenstein on Following a Rule,” in Synthese 58 (March): 325-364. 16 10 Some could posit that even if Kripke’s proposal fails, a communitarian approach that conceives the meaning of the rules in terms of social facts, i.e. facts constituted by the consensus of the members of the community in the judgments they accept, may succeed in answering SI. Yet, this movement restates some of the problems Kripke’s position raises – the problem concerning the objectivity of the norms -the impossibility to account for the individuals acting in virtue of the norm instead of merely in conformity with the norm. It is apparent that, the lack of an account of the objective character of norms, the fact that they have an external binding on human behavior, is not independent of their first-personal character, i.e. of the fact that they are presented to the subject as demands on their thoughts and actions. The central problem of the communitarian approach, in its different versions, is that it does not account for the reasons of the subject as reasons, the conception of which, the subject is selfconsciously responding to. Instead, it views the individual as directly responding to others. This, however, obliterates a crucial distinction between someone answering to a norm, in virtue of what it demands of her, and someone merely responding to the other’s conception of what he is doing. Moreover, as we have already noted, the appeal to social communitarian consensual facts would amount only to concurred opinions and it will thus still require an account of what makes those opinions meaningful and, if so, correct or incorrect. B. Agreement through Interpretation. The Interpretationist Approach. The notion of agreement plays an important role in a widespread account of language and rationality, whose most important representative is Donald Davidson, This could be referred to as an interpretationist model.18 According to this model, being a conceptual creature is being a language user. Both notions are accounted for in terms of interpretation: being a conceptual creature means being able to interpret other creatures’ actions as meaningful, the interpretation of language is a part of the global task of attributing meaning to other creatures’ behavior. To interpret someone is to attribute meaning to her conduct, conceiving of it as oriented by desires, beliefs and other propositional attitudes in the context of a common perceived world. In summary, interpreting someone implicitly involves constructing a 18 Others that can be considered representative of this model are Stalnaker and Grice, among others. I will focus on Davidson’s and Brandom’s positions but a similar objection can be raised to their proposals, with the corresponding adjustments to their particular arguments. See Satne (2010). 11 theory about the content of their beliefs, desires and the like, in the context of a world where both the interpreter and the one interpreted are commonly situated. In this case, agreement is shaped through what Davidson calls the principle of charity, which imposes on interpretation the methodological demand of optimizing agreement between the beliefs of the interpreter and those of the interpretee. In his “Radical Interpretation”, Davidson already describes this principle not as an “assumption about human intelligence that might turn out to be false,” 19 but as that in which taking the other to be rational consists in. It is a principle constitutive of rationality: it is simply impossible to interpret someone else as being rational without assuming at the same time that most of her beliefs are true, generally coherent and caused by the same objects (understood as distal stimuli) that usually are the source of our beliefs.20 We can thus find in Davidson’s account the transcendental perspective that seemed to be implicit in Wittgenstein’s conception of agreement: agreement among human beings is a condition for the possibility of rule-following and for the very use of language. It goes beyond mere agreement in natural history and cannot be expressed in an empirical proposition that could turn out to be false. 21 It is constitutive of what makes us rational beings. In this same sense, the Davidsonian triangulation is transcendentally conceived as a condition of the possibility for thought and language. The model of triangulation22 precisely presents a conceptual dependence between linguistic interaction with someone else and the distinction between belief and objective truth. Such notions are mutually dependent. Triangulation presupposes the existence of causal relations between two people and a common environment (causal origin of beliefs) and an interpretative relation between them (communication) governed by the aforementioned principles of Davidson, “Radical Interpretation” in Davidson, Donald (1984), Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation, Oxford UP, Oxford, p. 137. 20 The principle of charity can be described as involving two principles: the principle of coherence and the principle of correspondence. The first involves treating the beliefs attributed to the speaker as logically consistent; the second involves assuming that the speaker is responding to the same features of the world that the interpreter would respond to under similar circumstances. Features of interpretation are then: (i) it is holistic; (ii) it is coherentistic; (iii) it involves conceiving a large number of beliefs shared by the speaker and interpreter as true. According to Davidson, successful interpretation invests the person interpreted with basic rationality and that means that there is a shared interpersonal standard of consistence and correspondence, one which contains the very concept of rationality. See Davidson, “Three Varieties of Knowledge”, in Davidson, Donald (2001), Subjective, Intersubjective, Objective, Oxford UP, Oxford, p. 211. 21 See Thompson….. 22 See Davidson, “Thought and Talk” in Davidson (1984) and “Rational Animals” and “Second Person” in Davidson (2001), for the first re-elaborations of his theory in terms of triangulation. 19 12 rationality, through which they conceive of each other as reacting similarly to the same world. That being said, the kind of agreement constituted in triangulation is nevertheless insufficient as a criterion for the truth of contentful states. The principles of rationality state that most of the beliefs have to be treated as true but do not clarify which beliefs should be so treated. Thus the question as to how the interpreter’s contentful states are contentful and have a normative status remains, i.e. how is it that these states provide the subject with criteria to assess and correct her own behavior. Moreover, since agreement between the interpreter and the speaker is accounted for from the point of view of the interpreter, this implies that the criteria for the interpretation of the speaker’s states and words are also devoid of any normative content. As a result, we fall back into privatism since the very possibility of accounting for the external binding of content is lost23. Furthermore, as a principle of interpretation, agreement can be attributed to any creature or artifact24 and hence does not capture anything specifically related to what Wittgenstein has called an agreement in form of life; it fully depends on the thirdpersonal interpretative attitude of the interpreter. Attributing beliefs to another person or to a non-rational creature or artifact is perfectly admissible and the only relevant discrepancy in such cases arises from behavioral differences that can be observed from the third-personal perspective. So when attributing beliefs to others, the attributed concept of rationality does not involve sharing a common structure of responsiveness towards reasons that are first personally shared. But treating someone as rational cannot consist solely in interpreting him as responding to my conception of what constitutes a reason for what. If that were so, there would be no distinction between acting according to the norm and acting in virtue of the norm that it is. 23 The first remark concerns the first-person acknowledgement of what she is doing, the second the knowledge and assessment of the other person’s behavior. 24 Davidson addresses this criticism in several places (…) purporting to distinguish between humans, artifacts and other animals by describing a set of things humans can do and other creatures cannot. But the problem does not concern the act and activities that each of these beings can perform. One can imagine a case where the creature we are considering is exactly like us in all behavioral aspects even though it is an artifact or an alien. If asked whether this being would agree with us in our form of life, we would not necessarily answer “yes.” See Thompson, “A Puzzle about Justice”, pp. 378-9. In Davidson’s theory, the answer would have to be “yes”, but as Thompson has underlined, it would be possible for such beings not to be bound by our same norms, even if they would be interpreted as being bound by them. So the question would still be whether they are bound by our norms. And the fact that question is still open in itself reveals that we’ll need a different answer. 13 Brandom enriches the interpretationist treatment of normativity by including in his account the dimensions of authority, which is bestowed onto someone who is treated as someone entitled to a belief, and that of responsibility, which is properly demanded on someone when she is interpreted as committed to a certain belief. In the author’s proposal, interpretation then depends on the attribution of normative attitudes such as commitments and entitlements and the relation of incompatibility among the contents attributed. In his account, unlike Davidson’s, agreement is not a primitive notion but a contingent result of the interpreter’s theory, that may or may not hold true when comparing the speakers’ attitudes. The notions of authority and responsibility in Brandom’s theory seem to provide a vocabulary that could contribute to the understanding of the nature of mutual exchanges, exchanges that govern the way in which speakers consider that the other is responding to normative contents. However, the issues that affect Davidson’s account seem to also hinder Brandom’s treatment of such notions as far as his use of them relies on a conception of social interaction that conceptually depends on the third-personal stance of an interpreter.25 Once again, the point of view of the interpreter jeopardizes the normativity of conceptual contents and brings the risk of obliterating the crucial distinction between rational beings and other beings to which rationality is only attributed.26 Hence, neither Davidson nor Brandom can respond adequately to SI, i.e. to the question of what form social interaction must take in order to exhibit the normativity of meaning as an external binding and a pattern of assessment for the individual’s behavior. As I have presented it, SI requires a characterization of social interaction capable of showing how norms have an external binding on us and, at the same time, function as criteria of assessment of the individual’s behavior. Interpretationist accounts such as Davidson’s and Brandom’s stress the mutual assessments involved in normative behavior but since they conceive of them in terms of interpretation, they lose the external binding that reasons must exercise on the subject’s states. There is no coherent account of the external binding of the interpreter’s mental states or of how she can asses 25 Brandom himself acknowledges this proximity of his own notion of a deontic scorekeeper and Davidson’s notion of interpreter in Brandom, Robert (Ms), “Conceptual Content and Discursive Practice”, available online at http://www.pitt.edu/~brandom/mie/2421-w3.html, p. 32, and in the final chapter of Making it Explicit, where he argues that the external interpretational stance taken towards a foreign community coincides with the internal stance of the members pertaining to the community. 26 Note that Thompson’s puzzle would affect Brandom’s interpretationist account as well. See n. 24 above. 14 her own conduct in terms of correction. The problem is that the interpreter’s point of view is incapable of being corrected directly by the way the world is presented to her and the possibility of her being corrected by others is completely up to her. From the point of view of the interpreter, there is no real assessment on the part of the person interpreted of her own behavior since she can always interpret someone else’s conduct and beliefs as agreeing with hers by merely making the relevant modifications (remember that her interpretative task involves the holistic interpretation of language as well as the different propositional attitudes of the speaker). It follows that, in this account, there is no constraint on the interpreter’s propositional attitudes that could be described as normative. As previously noted, another issue that affects interpretationism —which is also a consequence of the interpreter’s privileged point of view in describing rationality—is that it is incapable of drawing a line that could distinguish rational beings (beings that are subject to norms by conceiving of them as norms they are subject to) from beings that merely act in accordance with reasons. This account then fails to accommodate the conditions of adequacy, the need to account for a first-personal presentation of norms and the one concerning its objectivity, it is thus incapable of meeting SI in a way in which the individuals involved in the normative relation could be said to be bound by the same norms, or have shared the same normative act. In order to provide an answer to SI capable of fulfilling these requirements, which neither the interpretationist nor the communitarian strategy has fulfilled, I will claim that it is necessary to abandon both the third-personal and first person plural perspective that characterizes such approaches. If neither the third-personal standpoint nor the appeal to a communitarian ‘we’ can provide an adequate account of what SI requires, I will argue that introducing a second personal perspective is a better-fitted candidate for the job. In the next section, I will present my own proposal. In order to provide an adequate answer to SI, we’ll need to pay attention to the way in which the norms that we share may be intersubjective patterns of correction. As I will claim, the practice of correcting one another is a suitable response to SI. It amounts to a kind of exchange that makes the actual sharing of norms and conceiving of the other as a first-personal autonomous subject a requirement for the possibility of an individual to be able to self-consciously share norms. Hence, I will suggest, when we consider the practice of correcting each 15 other the first-personal and the objectivity requirement previously presented are revealed to be themselves essentially second-personal. III. Mutual recognition and the second person. SI required specifying the form social interaction must have in order to exhibit the normativity of meaning as an external binding and a pattern of assessment for the individual’s behavior (the objectivity of meaning and the first-personal nature of rulefollowing conditions of adecuacy). As we have seen, thinking of human interaction in terms of interpretation from a third-personal standpoint leads to a lack of responsiveness of the first-person perspective to normative criteria either coming from the world itself or from others’ assessments of her conduct. Furthermore, Interpretationism defines rationality in a way in which the beings that are actually conceived of as rational do not necessarily share reasons or any intersubjective patterns of correction in any substantial way. A communitarian we would not do the job either. It would not account for the objectivity of norms since there would be no external binding on the community as a whole – i.e. there will be no logical space for the community to be corrected in light of the norm. Nor would it accommodate the first-personal requirement, since from the individual’s point of view, there is no distinction between acting in virtue of the norm and acting in accordance with what the community does. It is thus apparent that sharing reasons involves treating them as intersubjective patterns of correction and that in order to account for the shared character of norms, we need a different account of such sharing.27 SI required that we specify the kind of social interaction in which the first-personal character of norms and their objectivity is exhibited. We could put the question another way and ask what it means for us to share the space of reasons, i.e. what makes us both rational and social subjects. There are several ways to answer this question. The most modest response – the one Frege first suggested – is that we are capable of thinking the same thoughts. But as has become apparent now, although this is necessary, it is not sufficient. The problem There is of course more to sharing the space of reasons. See Sellars…, § 36 and McDowell, “Autonomy and its Burdens”, p. Public Presentation, University of Valencia, 2007, unpublished. What is being underlined here are only the conditions under which the shareability of reasons manifests itself as a common norm in social interaction. 27 16 with this answer is that it presupposes that we are thinking the same contents without showing (a) in which attitude that sharing is knowingly manifest for the subjects, i.e. the fact that they both know that they are sharing a thought, and (b) how is it that this sharing is not a mere possibility but something that is actually done. Hence, there will be no way of showing that the thoughts we are thinking are the same thoughts and that the very fact we are both thinking them is relevant to their normative force.28. A possible way to address the problems of the position described above is to include the fact that we can think that the other is thinking the same thought I am. This is what Davidson’s interpretation accounts for. Yet, as we have shown, this does not suffice to fulfill the required conditions for SI either. Again, this account does not satisfy either (a) or (b) above, and only specifies what it would take to treat someone as acting according to reasons but not in virtue of them. The latter requires the sharing of the space of reasons to be exhibited in a way in which both subjects knowingly follow the same rules and are aware that they are both following the same rules, i.e. exhibited as something they are in fact doing and not merely being interpreted as doing. The knowledge in question should be a shared knowledge. The need for each of the subjects to know he himself and the other herself are thinking the same thought is the central idea of Michael Thompson’s “You and I.”. This work describes what it means for a plurality of subjects to be able to (self-consciously) think that they are thinking the same thought. In spite of the obvious advantages of Thompson’s account vis-à-vis the previous one considered, his depiction still falls short of providing a comprehensive understanding of what SI requires. Thompson can account for the fact that I think ( as part of my very thought) that there is another conscious subject thinking the same thought as I am (e.g. that in the act of marriage we are having a thought that involves both of us consciously considering the act, i.e. she herself is marrying me myself when I myself am marrying her herself). Thompson’s description seems to capture the fact that it would be knowingly manifest for the subjects that they are sharing a thought when they are so doing, because part of the content of the thought in question would be that there is another self-consciousness thinking the same thought. But this awareness is 28 Anscombe and Castañeda (among others) have already critically noted that there are different thoughts that can be expressed with “I”, “you”, “he” and other pronouns; some additions are needed in order to capture these differences, differences that Frege overlooks entirely. What I am pointing out is not only that systematic ambiguity that may still be present in Frege’s Begriffschrift but also that the problem at stake here, i.e. the communality of norms, requires special devices establishing that the same thought is that which is thought by two or more different people. 17 no more than the mere possibility that there is another subject who is actually sharing the thought in question; in addition, the author’s description would require for this thought to be an actuality and not a mere possibility (the satisfaction of the (b) condition above). This means that in Thompson’s picture it is not essential for the norms to be actually shared. But SI required an account of the way in which the sharing of the norms exhibits itself in practice, i.e. in a practice that is already one in which the individuals are following the same norms. Following Wittgenstein, if agreement is essential to rulefollowing, one may think that agreement involves not only the shareability of thought but actually sharing norms, something which differs from mere shareability. The question still remains as to what form social interaction must take in order to exhibit the actual sharing of the space of reasons; the fact that the individuals are bound by the same norms that goes beyond its mere shareability 29. One essential feature of intersubjectivity as different from interpretationism and communitarianism is that it involves a second-personal relation. This second personal relation has been characterized in diverse ways by different authors. 30 Thompson himself seeks to represent second-personal relations on the level of logical form. Nevertheless, it seems that one essential feature of the second-personal relation involves a distinctiveness of roles that is necessary to capture the essentially relational trait that is distinctive of the social interaction. As Moran has pointed out, what is special about a second-personal relation is that it involves some form of directionality from one person to the other that cannot be accounted for in evidentialist terms as it would be in the third-personal model. 31 This shows that in order to understand a second-personal relation, the question is not only the communality of the thought or norm that binds us together but also the distinctiveness of the person who is an “I” and the one who is a “you.” What I will claim is that this distinctiveness plays an essential role in exhibiting the normative force of the thoughts that we think together. Hence, Thompson’s depiction could be enhanced by a characterization of social interaction that does not merely show the other’s self-consciousness as a possibility but instead as necessary in the very existence of shared norms. The latter, I will claim, involves the distinctiveness of roles that, as it will be shown, accounts for the special To put it in terms of agreement, from the point of view of Thompson’s picture, there is no difference to be made between the mere possibility of agreeing and the fact that we actually agree by thinking the same thought or by following the same rule. The latter is essential to account for social interaction in the comprehensive sense SI requires. 30 See Moran, Rödl, Thompson, Darwall…. 31 See Moran (2005)…. 29 18 normative force of second-personal relationships, as we will see. The very idea of rational demand is what must be included, i.e. the fact that the norms that she herself binds herself to are the ones to which I must bind myself. I have claimed that only a second-personal interaction is capable of exhibiting the shareability of reasons in the sense required. More specifically, the interaction must be one in which the very fact that the other is a rule-follower, i.e. an autonomous rational subject, is exhibited. And that kind of interaction is none other than the very practice of correcting each other32. Intercorregibility seems to be the crux of our normative exchanges. When interacting with others, acting rationally involves taking into account (i) the reasons that others may present which conflict with ours and (ii) their assessments of our conception of what constitutes a reason for what. We can describe what is involved in this kind of intersubjective relationship in a twofold way: (1) the subjects must be responsive to each other’s assessments of their conduct – they are mutually responsive to correction and (2) the subjects’ grounding of their mutual assessments is their conception of the reasons as the reasons they are. So the practice of intercorregibility presupposes that we are sharing the same norm and that we are bound to it by conceiving of it as a common pattern of assessment. Thus, intercorregibility as a form of interaction amounts to treating the other person’s assertion as a reason for acting or thinking in such and such ways. That involves treating the other who is assessing me as self-consciously following a norm— and the same norm as the one we are following. Acting this way requires that the individual grants authority to the other with whom she is interacting while holding her responsible for her actions and reasons. Both attitudes should be understood as constitutive of our rationality. As Moran (2005) has underlined, what is specific to second- personal exchanges – ‘tellings’, for example - is that they cannot be accounted for in third-personal evidential terms: the subject is presenting an assertion as a reason to believe something and as such is taking responsibility for that very act. This of course requires self-consciousness. Such responsibility lies on her being held responsible by an audience which she consciously addresses. Intercorregibility as such presupposes the notions of responsibility and holding accountable as two distinct attitudes that the subjects assume towards one another. Such 32 I have developed this in relation with the capability of learning a language in Satne (2009). 19 distinctiveness is present in the case of telling, but it proves itself as a more pervasive feature of our rational practice of treating one another. It is a practice that can be directed towards any use of our rational capacity. We can correct each other in any case in which we exercise our rational capacities. Unlike the merely external similarity of responses characteristic of consensus and the attribution that the action of the other concurs with mine, taking into account the criticisms of others in the practice of correcting each other– both as a pattern of assessment for my behavior and as a reason to act – requires thinking that THE OTHER IS rational, i.e., that you have a self-conscious first-personal presentation of the norm and, at the same time, that we are bound by the same norm. These two conditions are precisely those we suggested SI required us to accommodate. The first-personal character of norms and their objectivity are thus revealed to be essentially secondpersonal when we consider the very practice of correcting each other: it shows that we are beings that may act in virtue of shared norms, norms to which we bind ourselves together. It is clear that considering someone else’s reasons as relevant to my own conception of what is a reason for involves treating each other as rational in a way that goes far beyond the mere interpretability of her conduct. It presupposes that she shares the space of reasons and is as rational as I am, and hence is accountable for her conduct and with the authority to assess my own conduct prior to any attribution of mine. This means that to recognize someone as rational is to treat her as rational by assessing our own conduct in the light of her assessments and the reasons she presents, and involves the ability to change our conduct in the light of her criticism. This is why intercorregibility is a pervasive trait of our rational practice and exhibits that to the very possibility of such practice underlies an a priori structure of mutual recognition.33 Contrary to the communitarian approach, the order of reasons does not depend on the subject’s attitudes. Instead, her actual acknowledgment of another subject is only possible in virtue of sharing that order – cohabitating the space of reasons, as Sellars would put it. That order is thus the grounding of factual acknowledgments and not the other way around. Actual agreements are then not merely random – as the 33 This idea has been developed in detail by Brandom to understand the cohabiting of the space of reasons. Nevertheless one of the points here made is that this structure is exhibited in second personal non-interpretative stances. 20 characterization of merely similarity of responses may imply – but made possible by an a priori structure of mutual recognition. Thus, the a priori structure of mutual recognition makes agreement a transcendental condition for rational behavior, instituting a normative principle according to which we must agree on what constitutes a reason for what. Drawing this transcendental distinction involves differentiating between agreement as a transcendental requirement and actual agreements in practice, one being the condition of possibility of the other. This is what I believe Wittgenstein is be drawing our attention to when he emphasizes that the relationship between agreement and rulefollowing is not empirical but grammatical, i.e. that it defines what it means to follow a rule in general34. The previous considerations have brought to the fore the idea that agreement plays a significant role when trying to account for the objectivity of norms. The communitarian idea by which this objectivity is understood to result from a factual agreement reached by the community as a whole is nevertheless, as I have attempted to show, misguided. The relationship between agreement and objectivity cannot be understood as if a factual agreement were the criterion for the normativity of norms. Yet that does not mean, as Davidson claims, that a shared language is not required in order for interpretation to be possible. If there is to be both objectivity and normativity, a shared order of reasons – and a shared language in which that order is exhibited – is required35. Hence, accepting the importance of agreement for normativity does not commit us to accepting a reductionist view of norms that makes the objectivity of reasons dependent on communitarian consensus. The community is not what warrants 34 Two observations are worth making at this point. My position can be characterized as a form of quietism, if understood as the idea that it is not possible to account for conceptual practice in a way that does not already presuppose it. This is so because the a priori structures and the principles that derive from them are not to be conceived of as independent from that practice. On the contrary, their validity “is only established with reference to their operation within the particular structure they are part of,” (Malpas, 1997, 13-4). However, that does not mean, and this is the second observation, that it is not possible to deploy a philosophical discourse on the conditions of possibility of such a practice. The discourse on such conditions can be understood as explicitating the structures involved in the actual practice. Although more should be said about the specific mechanisms of explicitation (see Satne, 2009), our being participants in that practice is what makes us capable of making the principles that govern it explicit ( see Brandom (1994) and Brandom (2008)). 35 This proves false Davidson’s claim that it is not necessary to learn how to speak as others do to become a speaker. On the contrary, to be rational, to speak a language, or, as McDowell would put it, to be a “potential participant of an encounter with others that leads to mutual understanding,” (McDowell, J., “How not to read Philosophical Investigations: Brandom’s Wittgenstein”, in McDowell, J. (2009), The engaged Intellect, Cambridge, Harvard UP, p. 143) is essential to learn and come to share ways of speaking. 21 normativity in the sense that Kripke believes it does; instead, being a member of a community is nothing more than sharing a set of reasons. The objectivity of reasons is a condition of possibility for the sharing of reasons; this shareability manifests itself in the community practices as factual agreements among its members and is as such an a priori condition of the practice of exchanging reasons. That is why, as McDowell pointed out, the community in question is potentially infinite, crossing cultural and historical boundaries. Of course, how we actually share reasons and which reasons we do share may depend on cultural factors since the understanding of reasons involves the exercise of our rational capacities that, as such, is temporal and a part of the empirical world. To summarize, we can only account for thought as essentially social, and present the specific way in which this social aspect of thought manifests itself through human interaction, if we consider that the social interaction at stake is distinct from a merely external similarity of responses and also different from the one resulting from an observer’s attribution of beliefs. The question I have stressed is what kind of interaction between rational beings manifests the objectivity of reasons as a criterion that is shared for the correction of the actions of each of the subjects involved in the interaction. I have claimed that answering this question requires distinguishing the order of reasons and the way in which this agreement manifests itself in social interaction. Secondly, I have argued that if the specific sort of social interaction that is in question involves manifesting the shareability of reasons, it cannot be understood as a coincidence in reactions or opinions that could be characterized as consensus or as a third personal interpretation of one’s behavior as conforming to the order of reasons. The practice in question presupposes the capability of sharing the same norm, and thus a thought that involves a plurality of self- conscious subjects capable of thinking it together, Nevertheless, we were seeking an account of the actual shared character of norms. I have claimed that this should be understood through a second-personal kind of interaction that involves both a transcendental and an empirical dimension. The former is the a priori structure of mutual recognition that corresponds to reasons as such while the latter amounts to the actual mutual acknowledgement in practice as well as to the conceptions of what constitutes a reason for what that emerge from it. The former counts as a condition of possibility for the latter and, by the same token, of the distinction between what seems correct and what is correct that lies at the basis of normativity. 22 We have departed from a puzzle about norms and institutions. It was a puzzle about the notion of community i.e. of how to understand the sharable character of norms and of them being actually shared by individuals. How is it that individuals bind themselves together under the same norms? We can now see that community is a primitive notion to be understood in terms of mutual recognition. To be a communitarian subject amounts to exercising the capability of engaging in second personal interactions that are themselves the manifestation of an a priori structure of mutual recognition. At the same time, being part of a particular community requires engaging in actual practices of mutual recognition that define that community in terms of the conceptions of what constitutes a reason for what, i.e conceptions those individuals endorse as shared patterns of assessment of their behavior. Mutual recognition is exhibited in our actual second-personal exchanges of correcting one another. These second-personal exchanges reveal our transcendental capacity for sharing the space of reasons that is constitutive of rationality; and, at the same time, are the means by which we autonomously assume that capacity as the most rational way of inhabiting the world. 23