Microsoft Word - Ulster Institutional Repository

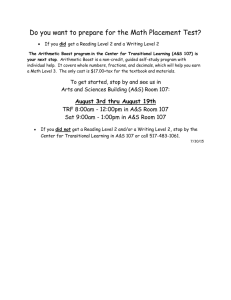

advertisement