philosophical notion

advertisement

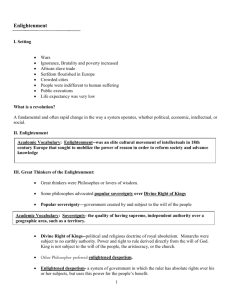

Shama Adams Conceptual Contingencies: The Notion of Progress and the Idea of “History” Principia Historiae: Theories of History and Murmurs of Progress Celebrated mathematician and logician, Bertrand Russell once remarked: “A process which led from the amoeba to man, appeared to the philosophers to be obviously a progress, though whether the amoeba would agree with this opinion is not known.” Whilst I’m sure that many of you share my fondness for humorous intellectual anecdotes, this quote also serves to remind us that notions, judgments, and ascriptions of the idea of progress, especially progress in history, are always a matter of context and subjectivity. Progress is not unproblematic. However, it is fair to argue that progress is a discrete philosophical concept which emerged during the Enlightenment, and remains embedded in the broader philosophical systems prominent during this time, namely German Idealism, and French Humanist Rationalism. Far from being a generic or simple term which refers broadly to scientific or technological development, the idea of progress is a way or modality of seeing. The idea of progress is a product of specific historiographical and historical transformations during the long eighteenth century, namely profound changes in the ways in which history was written and employed, and the raison d’etre of history itself. The categorisation of progress as a discrete philosophical concept in my research and this paper specifically, is based on the realisation that, through a survey of Classical and Enlightenment philosophy, the idea or “Geist” (to borrow the Hegelian term) of progress operates as the “ghost in the machine.” That is, as a phenomenon which seems innate or inherent, and is therefore rarely fully actualised or singled out for philosophical analysis or critique. This assumption masks the culturally constructed and contextually contingent nature of progress, and leads to the concept being further conflated with dominant narratives of history and the Enlightenment itself. Shama Adams Progress, theories of history and the Enlightenment, whilst mutually inextricable, are not philosophically synonymous, and nor are they intellectually interchangeable concepts. The Enlightenment’s collective assumption that progress is inherent in history can be explained, in part, by the fact that progress is both a concept, and a historical narrative which is deeply enmeshed in, and conflated with, numerous, interrelated concepts, including but not limited to, secularism and humanism. As several of my colleagues have emphasised throughout the proceedings of this conference, history is not innate, natural or unproblematic. Rather, history is a contrived intellectual and institutional construction, which is temporally and culturally specific. Whilst notions of history begin in Antiquity, nuanced theories of history were not fully-actualised for many centuries later, during the Enlightenment. “History” itself, is also contingent on several intellectual precursors which predate its conceptualisation; namely, an understanding of time, and, historical consciousness. Hence the discipline of history has a history of its own, and it is impossible to talk of progress without intimating universal history, and it is equally difficult to invoke contemporary understandings of universal history without inferring a sense of progress. However, it is necessary for heuristic purposes to deconstruct this intellectual conflation, and demarcate the discreet qualities and unique histories, of both concepts. The notion of progress lends itself favourably to a specific way of both interpreting and writing history, that is, universal history. Whilst it is my contention that universal history, (at least as we understand it today), is product of the eighteenth century, attempts to write versions of universal history have been made long before the Enlightenment. For example, as early as the fifth century C.E, the Roman, but Early Christian historian, Paulus Orosius in his History Against the Pagans strove to construct an account of history which was accessible and relevant to humanity as a cohesive whole, as opposed to the parochial epochs. Similarly, St Augustine’s City of God, also fifth Shama Adams century C.E, intimates a version of universal history, as it concludes that the central plan and purpose of history is the unfolding of God’s will throughout the ages, for the whole of humankind. So we begin to see that Judeo-Christian accounts of history, by virtue of their respective author’s beliefs in providence, could not help but be thematically universal, even unwittingly. However, the impetus to construct explanatory narratives of universal development, which were for the first time in history, markedly and deliberately human-centred and dismissive of the idea of divine providence, grew manifestly stronger in the years after the Reformation. I think the reasons for this “humanist universal impulse” are numerous, but the most significant of these reasons can be broadly identified as: 1. The rise of secularism and the gradual wane of religious authority on public and private life, since invention of the printing press in particular. 2. The rise of empiricism, and the growing belief that empirical science and reason would advance the cause of humanity, whereas religious edict and superstition were regressive forces. 3. Interestingly enough, the European power’s colonial and imperialist expansionalist projects in far-flung and previously “unknown” parts of the globe. Succinctly put, as Europeans began to “discover” more of the world, it seemed only natural that philosophers might attempt to unify or at least account for the seemingly disparate anthropological histories of the world’s various cultures, and this is exemplified by the numerous attempts at constructing “universal histories” which began to emerge during the long eighteenth century. Voltaire writes: Everything speaks to us, everything is done for us. The silver on which we dine, our furniture, our new needs and pleasures, everything reminds us that all parts of the entire world, have been joined for the past two and a half centuries, thanks to the industry of our fathers. No matter where we go, we are reminded of the change that has taken place in the world. Shama Adams According to Voltaire, the momentous developments of the past two centuries had both precipitated and necessitated that history now be written from a universal perspective. He and others advocated for a new model of historiography, which placed emphasis on distinguishing fact from fiction (something which ancient and medieval historians had problematic degrees of compliance with!) by way of close reference to historical documents, stressed the critical evaluation of these sources of evidence, and was to deliberately focus on modern history as opposed to ancient history, as methodologically, knowledge of the recent past was thought to be more certain and easier to obtain than knowledge of the distant past. Voltaire remarks: “Modern history has the advantage of being more certain, because of the very fact that it is modern.” This universal method gained popularity, and was gradually institutionalised, in the sense that it became, (and arguably remains to this day) the dominant theory of history under the auspices of the French writers and religious scholars the Abbé Bossuet, preceptor and tutor to Louis XIV’s young daughter and heir-apparent son, the Dauphin, and the philosophes Voltaire and the Marquis de Condorcet. Published in 1681, Bossuet’s Discourse on Universal History, was specifically written for the educational instruction of the Dauphin, though it is clear that Bossuet also intended the text to have a much wider audience. Though self-defined as a universal history, it is perhaps better described as a history of the Greek, Roman and early Christian worlds, with the occasional mention of a wandering or invading, but always transient civilisation which falls outside of these specific and limited groupings. These limitations aside, the Abbé’s central argument is that from the creation of man to the present day, the Judeo-Christian religion has been one and continuous, whilst in the same interval, a succession of mighty empires have passed across the stage of history and disappeared, and it therefore naturally follows that the stability of this religion can only be (reasonably) accounted for by way of the special conservation of a Divine Providence. Bossuet argues: Shama Adams Thus I have no more to say upon Universal History. You will discover all its secrets, and it will now be in your own power to observe in it the whole progression of Religion and succession of great empires down to Charlemagne. While you see them fall, almost all of themselves, and shall see Religion support itself by its own power, you will easily understand what is solid greatness, and wherein a wise man out to place his hope. Murmurs of Progress The notion of progress has a complex and conflated, linguistic, philosophical, and cultural history. Historian Sidney Pollard defines progress as “the assumption that a pattern of change exists in the history of mankind which consists of irreversible changes in one direction only, and that this direction is towards improvement” (16). In common usage, the word progress has come to be tacitly synonymous with notions of advancement, improvement and growth. Finnish philosopher and mathematician Ilkka Niiniluoto argues against this common understanding, and states that progress is an “axiological” or “normative” concept which should be distinguished from neutral descriptive terms such as “change” and “development”. According to Niiniluoto, inherent in the notion of progress are ideological assumptions, investments and value judgements. From the nineteenth century onwards, progress came to be increasingly associated with notions of development and advancement as they pertained to science and technology. This can largely be attributed to the successes of the Industrial Revolution, and the pervasive belief that scientific discovery, coupled with technological innovation, would transform society for the better. In our late-modern and increasingly technocentric culture, it is difficult to separate progress from notions of technological development. The idea that progress is mutually synonymous with technological advance is a product of and a testament to the cultural supremacy of empiricism.1 As historical philosopher Ronald Wright explains: “our culture measures Shama Adams human progress by technological means because it delivers - the club is better than the fist, the arrow better than the club, the bullet better than the arrow”. Further, historian of science George Sarton argues: “the acquisition and systematization of positive knowledge are the only human activities which are truly cumulative and progressive,” and “progress has no definite and unquestionable meaning in other fields than the field of science”. Technological progress has become the modus operandi primarily because it is quantifiable, and hence immediately discernible. Philosophical and social progress are more difficult to define, much less measure. However, this dominant and common-sense view is problematic, and needs to be deconstructed. Progress does, indeed, have a definite, though contentious meaning in fields other than science, and these meanings are culturally and contextually constructed. Historian Sidney Pollard notes that the idea of material progress is a very recent intellectual development, one that has occurred only in the past “three hundred years.” The Turn to Philosophy Progress has often been seen as the logical outgrowth of the secularisation processes of the Renaissance. However, I would argue that it is changes in the disciplines of philosophy and history themselves, which promoted the belief that the past should be read as the story of humanity’s rise towards civilisation, and that progress was the conduit which necessitated and made such a reading possible. These changes were temporally and culturally specific to Europe, expressly the rise of a sense of European cosmopolitanism, and the Enlightenment’s quest for universalism and the universal foundations for knowledge grounded in reason. Neither Classical European, nor Renaissance history, conformed to this new, benchmark. The solution was to infuse thinking into historical scholarship, and to make history factual, scholarly, and above all, philosophical. Voltaire’s intellectual contemporary, the historian and champion of public education, Charles Rollin argued Shama Adams that fundamental purpose of history was to take us beyond the confines of our time, and that philosophy was the conduit which could make this understanding possible. There is an eighteenth century urban myth which is as follows: The early composition of the new genre of history was in part, a result of a complaint made to Voltaire, by the Marquise du Châtelet that history was “unpalatable”: A confused mass of unrelated facts, a thousand accounts of battles which have decided nothing. What is the point for a Frenchwoman like myself of knowing that in Sweden Egli succeeded Haquin and that Ottoman was the son of Ortugul? Voltaire concurred with the criticism, and set to work on his own, secular continuation of Bossuet’s Discourse on Universal History. Voltaire titled this piece: The Essay on the Manners and the Spirit of the Nations (1756.) In re-conceiving and re-imagining history and origins, the philosophe attempted to reduce facts to a minimum and concentrated instead on broad, cultural patterns. Voltaire writes: “in this history we shall confine ourselves only to that which deserves the attention of all peoples and of all ages” (75). He thus strives for a purposeful universalism, and this is consistent with the Enlightenment’s attempt to procure the universal foundations of knowledge, grounded in empiricism and reason. Hence, the practice and purpose of history was changing. This change can be attributed to both the burgeoning development of the concept of progress, and the belief that human progress in history was universal and unassailable. Rollin emphatically states: “Confined to the bounds of the age and country wherein we live, and shut up in the narrow circle of such branches of knowledge that are not peculiar to us, and within the limits of our own private reflections, we remain ever in a kind of infancy, which leaves us strangers to the rest of the world, and profoundly ignorant of all that has gone before us, or indeed, even surrounds us now.” Shama Adams Progress, Universal History, Enlightenment The Enlightenment, generally understood as spanning between the late seventeenth century and the early nineteenth century, is the period in which the concept of progress was theorised philosophically. The concept in turn became reified, and was transformed into both a narrative of history, and the raison d’être for history itself. It is also during the Enlightenment that progress came to be the secular purpose of humanity, culture and civilisation. The first systematised conceptualisation of progress to emerge during the Enlightenment was the French rationalist Nicolas de Condorcet’s posthumouslypublished treatise Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind (1795). An avowed and unrepentant atheist, Condorcet’s work encapsulates the rational spirit of the Enlightenment, and the Marquis was the only philosophe to witness the Revolution and participate fully in its constitutional aftermath. A celebrated thinker and reformer, Condorcet’s ideas were often radical and prescient, and it is this foresight which makes so much of his work still relevant to the pertinent issues and conditions of our own time. The eternally optimistic Condorcet argues that progress is inevitable, and believes that future societies will surely be rational and prosperous, as their systems of knowledge and ethics will be shaped entirely by empirical science. Condorcet’s text constitutes a comprehensive theory of universal development, and is hence, though perhaps unwittingly, a thorough example of a fully-nuanced theory of universal history. In contrast to those versions of universal history in which the author’s premise, purpose and argument is grounded in religious precept and doctrine, such as St. Augustine’s or the Abbe Bossuet’s, Condorcet’s Sketch is wholly-secular and humanist in approach. This represents a radical departure from Bossuet’s thesis of history being the unfolding example of God’s everlasting providence throughout the fullness of time. Condorcet sites human initiative, action and industry as the motors of Shama Adams history, not supernatural patronage and intervention. For the Marquis, the persistent existence of religion and religious belief is seen as profoundly regressive, rather than progressive. As the German idealist Hegel saw the Prussian state and Christianity as being the ultimate fulfilment of historical development, Condorcet saw the cessation of belief in the supernatural altogether, and progress itself to be the continuing theme of, and development within, history. As a conclusion and coda to this paper, let us now turn our attention to the Post-Enlightenment. Owing to its entrenchment in, and conflation with, the Enlightenment, the notions of progress in history, and the idea of progress itself, in postmodernity, is problematic. Progress is seemingly incompatible with the ethos of postmodernity and postmodernism. French cultural theorist Jean-François Lyotard claims that the defining characteristic of postmodernity is scepticism towards all attempts to make sense of history, or imbue it with purpose. It is therefore not surprising that both universal history, and the concept of progress, receive a thorough trouncing in the post-enlightement. The post-Enlightenment’s unrepentant critique of the notion of progress can be attributed to what Lyotard describes as postmodernity’s “scepticism towards all metanarratives,” and to postmodern culture’s problematic relationship with the ideal of secularism, and by extension, theories of history. According to Lyotard, the Enlightenment functions as the definitive metanarrative of progress. Lyotard is critical of what he regards as the grandiose and prophetic claims of the Enlightenment, and its versions of universal history, (some of which I’ve discussed today), and sees postmodernity as the temporal and cultural context which will herald the collapse of the Grand Narrative and, moreover, that which is central to all others of the Enlightenment Project, namely, progress. Postmodernity, Lyotard argues, is post-history. But I think, (amongst other discoveries) that the proceedings of this conference have resolutely demonstrated that we have not arrived in Postmodernity just yet, for as Shama Adams we have seen, universal history, and history itself, are not mere or forgotten footnotes on the transcript of human thought. Rather, and as eminent historian and scholar, Edward Hallet Carr states: “history is an unending dialogue between the present and the past.” Universal models of history, whilst replete with their own internal idiosyncrasies and incongruences, invite us, as historians, to engage in a dialogue between our own contextual comfort zones and the multitude of cultural and temporal spaces outside of our limited, livedexperiences. As Bossuet ambitiously surmises: Particular histories show the sequence of events that have occurred in a nation in all their detail. But in order to understand with greater insight, we must know what connection that particular history might have with others, and that can be done by a condensation in which we can perceive, as in one glance, the entire sequence of time. And that my colleagues, whilst seemingly grandiose, should be viewed instead as an ambitious project to which we as historians can aspire to. Besides, history is in the making, refuting, and contesting. A static history is a dead history, a universal history, is one that in the words of the seminal Czech author, Milan Kundera, is there to “provoke and admonish us.” I’m leaving myself open to a barrage of question in the discussion time with this concluding comment, but I, for one, am happy to be provoked. Thank you.