File - Emily Suzanne Shields

advertisement

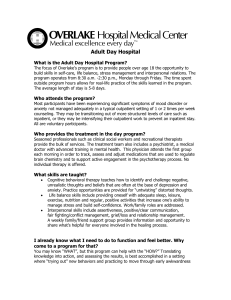

Emily Shields EDC 615 Midterm Exam Question #1 In 1963, President Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Centers Act into law, which established mental health facilities around the country to provide services that were previously only available in state-operated mental health hospitals. The purpose of this law was to remedy the inadequate level of care available for mentally ill individuals, address overcrowding in state institutions, and provide more cost-efficient and less invasive care for individuals who do not require inpatient treatment. The deinstitutionalization of mental health care was the first step in changing the mental health system into its current form. The Act served as a launch pad for mental health organizations to start providing an array of services, including outpatient treatment, crisis intervention, short-term inpatient care, partial hospitalization, and education services. Prior to 1963, individuals suffering from mental health issues were either institutionalized or continued to live in their communities without adequate treatment. The Act allowed clinicians to provide a range of services to help individuals on a broad spectrum of mental illness while allowing them to remain in their communities. With modifications in 1968 and again in 1970, the Act also instated alcohol and drug abuse treatment services and mental health care for children. As the mental health system shifted to a more community-oriented model, partnerships with other organizations and agencies were formed to help clients receive needed services, and multidisciplinary teams became a key element to providing treatment. The Community Mental Health Centers Act provided the framework for the current continuum of care, and offered individuals with mental health issues the opportunity to seek quality, individualized treatment in a more approachable community setting. Question #3 In many mental health care settings, such as licensed agencies, inpatient facilities, continuing day treatment, crisis intervention services, and intensive case management (among others), effective treatment is administered by a multidisciplinary team of mental health professionals. From intake assessments to treatment planning and counseling sessions, the needs of clients are often addressed by a team that works together toward the goal of recovery. This treatment model can be effective for clients presenting with multiple problems (such as diagnosable disorders or problems in living) because experts in each area attend to these problems directly. Clinicians with varying levels of training and areas of expertise work together to develop diagnostic impressions, treatment plans, and networks of support for each client. Interprofessional dialogue is especially important for multidisciplinary teams to keep up with each client’s needs, progress, and potential setbacks. Communication should be open and clear to continually evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment plan and ensure each individual’s growth and success. When a treatment plan includes pharmacology, it is especially important to address the impact on the client and the role of pharmacological drugs in recovery. Substance abuse and eating disorder treatment are examples of services that require continual client support by a clinical team. Follow-up is essential to treatment, and counselors risk client relapse and added trauma with weaknesses in professional communication. In case management situations, it is crucial for professionals to correspond regularly to ensure the right services are provided. In addition to the obvious client benefits of professional communication, clinicians can also benefit from the shared views and experiences of others. Even in a private-practice setting, counselors must sometimes seek outside sources for professional advice, and even referrals when specific expertise or additional help is needed for a client. Question #4 Currently, LMHCs in New York State do not have “diagnosis” explicitly written into their scope of practice. The present legal literature includes all manner of alternative language to describe the professional abilities and responsibilities of LMHCs, but stops just short of including actually diagnosing mental disorders. The omission may seem minor, but it presents a huge obstacle in many forms. The exclusion of diagnosis denies LMHCs proper compensation from insurance companies. Some insurance companies do not recognize LMHCs as qualified mental health care providers because of the lack of explicit legal terminology. Without a medical diagnosis from a clinician, most insurance companies will not cover mental health services for those covered by their plans. While other mental health professionals are legally qualified to diagnose, some have less clinical training than LMHCs, and some clinicians no longer provide counseling services – opting instead to primarily oversee pharmacological interventions. It is often implied (but not legally recognized) that LMHCs are properly trained to diagnose mental illness, and will do so in order to provide evidence that an individual is in need of treatment. This presents an ethical dilemma for LMHCs. Counselors offering services to insured clients are under pressure to provide a diagnosis, even if an appropriate one is not apparent. Diagnosis of a mental illness carries with it many consequences, including social stigma, future denial of insurance coverage, and permanent documentation. Clients with sub-clinical issues, problems in living, and/or no visible long-term diagnosis may require treatment of some sort, but without a clinical diagnosis they are ineligible for insurance coverage. In addition, LMHCs can be sued for violation of legal limitations. Until diagnosis is added to the scope of practice, LMHCs are constantly at odds with insurance companies, other mental health professionals, clients, and even the law. Question #6 The concept of recovery from mental illness is multifaceted and becomes more relevant every day as treatments become more effective. In previous years, recovery from serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, has seemed impossible. However, as our knowledge of mental illnesses has grown, and successful evidence-based practices have emerged as effective treatments, hope for complete or near-complete recovery for mentally ill individuals has increased. Different types of treatments from cognitive-behavioral therapy and dialecticalbehavioral therapy to pharmacological drugs and group therapy sessions are now regularly researched and evaluated, and treatment models are constantly revised. Peer support groups are often integral to recovery for many individuals, and it has been recognized that they offer a form of emotional encouragement that is vital for maintaining hope and progress during and after formal treatment. As the mental health field has advanced, so has knowledge of physiological brain function. Symptoms of mental illness are now more easily linked to specific brain abnormalities, allowing clinicians to identify problems and treat clients more successfully. However, while medicine has advanced, there are still obstacles facing individuals in recovery. A need for public education is still evident in the social stigmas attached to diagnosis. Often individuals with mental disorders are continuously branded with their diagnosis, regardless of time that has passed or effectiveness of treatment. Some scholarly literature has expressed the vital role a supportive family member or friend often plays in an individual’s complete recovery from mental illness. Someone who truly believes an individual has the capacity to recover can be as impactful as any formal treatment, which reinforces the importance of establishing a strong client-counselor bond as the foundation of treatment of any mental illness. Question #8 Continuing day treatment is an effective treatment option for many people who suffer from a variety of problems. It offers the stability of a consistent program with numerous avenues of support in an environment that is less invasive than hospitalization or residential treatment. The versatile nature of continuing day treatment makes it appropriate for all manner of issues, from eating disorders and suicidal thoughts to substance abuse and commonly debilitating mental illnesses. Continual support, education, services, structure, and supervision is provided for clients in a continuing day treatment program that goes above and beyond what most clinics can offer, yet allows clients to receive treatment while remaining in their communities. Consistent staff, regular progress checks, and a positive environment become the client’s allies and resources during recovery, ensuring both a high level of intervention and an important degree of independence. Continuing day treatment focuses on long-term recovery goals, as opposed to inpatient and hospitalization programs that are designed to quickly resolve an immediate crisis before moving a client into a less intensive treatment program. In contrast to continuing day treatment, acute inpatient psychiatric care is the highest level of intervention an individual can receive. The objective of inpatient care is short-term, comprehensive intervention that identifies and treats serious issues of mental health. Inpatient stays range from 30 days to six months. While a highly structured and supervised environment is needed for some clients with mental illness, inpatient care is also the most invasive. Clients are under constant supervision and live away from their homes. Since the implementation of the Community Mental Health Centers Act, and especially more recently due to cost-effective models, there has been a shift of inpatient services toward outpatient care. For clients suffering from severe mental health issues, inpatient treatment is a good option. However, for clients who can improve and regain functioning in a less costly and intensive environment, outpatient options are often explored.