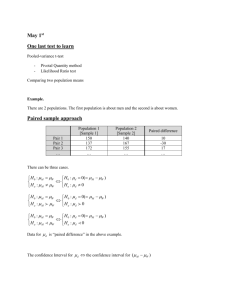

paper ()

advertisement