Click here.

advertisement

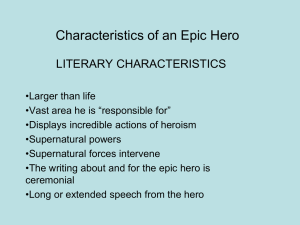

1 British Literature and Expository Writing II (Honors) Dr. Jamir 2015-16 LITERARY TERMS GUIDE Test Tues., Dec. 8 *The test format will be matching. 1. Alliteration: the repetition of initial consonant sounds. It is often used to emphasize and to link words as well as to create pleasing, musical sounds. Alliteration of stressed syllables is characteristic of Anglo-Saxon poetry. 2. Aside: a statement delivered by an actor to an audience in such a way that other characters on stage are presumed not to hear what is said. 3. Assonance: the repetition of vowel sounds in stressed syllables containing dissimilar consonant sounds. In the following example, the long “e” sound is repeated in the words “reach” and “exceed” in stressed syllables containing the dissimilar consonant sounds “rch” and “c-d”: “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp.” 4. Blank verse: poetry written in unrhymed iambic pentameter. It usually contains variations in rhythm that are introduced to create emphasis, variety, and naturalness of sound. Because it sounds much like ordinary spoken English, it is often used in drama and poetry. 5. Caesura: a natural pause, or break in the middle of a line of poetry. 6. Characterization: the act of creating and developing a character. Different types include direct – when character traits are revealed explicitly – and indirect – when the writer reveals traits by some other means. 7. Climax: in a story’s or play’s plot, the point at which the main character’s desire is irrevocably fulfilled or denied. 8. Conflict: a struggle between opposing forces. The opposition between two characters (such as a protagonist and an antagonist), between two large groups of people, or between the protagonist and a larger problem such as forces of nature, ideas, public mores, and so on. Conflict may also be completely internal, such as the protagonist struggling with his psychological tendencies (drug addiction, self-destructive behavior, and so on). 9. Couplet: two lines--the second line immediately following the first--of the same metrical length that end in a rhyme to form a complete unit. Geoffrey Chaucer and other writers helped popularize the form in English poetry in the fourteenth century. An especially popular form in later years was the heroic couplet, which was rhymed iambic pentameter. It was popular from the 1600s through the late 1700s. 10. Denouement (resolution): a French word meaning "unknotting" or "unwinding," denouement refers to the outcome or result of a complex situation or sequence of events, an aftermath or resolution that usually occurs near the final stages of the plot. It is the unraveling of the main dramatic complications in a play, novel or other work of literature. 2 In drama, the term is usually applied to tragedies or to comedies with catastrophes in their plot. This resolution usually takes place in the final chapter or scene, after the climax is over. Usually the denouement ends as quickly as the writer can arrange it – for it occurs only after all the conflicts have been resolved. 11. Epic: a long narrative poem originally handed down in oral tradition, later a traditional literary form – dealing with national heroes. An epic in its most specific sense is a genre of classical poetry. It is a poem that is (a) a long narrative about a serious subject, (b) told in an elevated style of language, (c) focused on the exploits of a hero or demi-god who represents the cultural values of a race, nation, or religious group (d) in which the hero's success or failure will determine the fate of that people or nation. Usually, the epic has (e) a vast setting, and covers a wide geographic area, (f) it contains superhuman feats of strength or military prowess, and gods or supernatural beings frequently take part in the action. The poem begins with (g) the invocation of a muse to inspire the poet and, (h) the narrative starts in medias res (in the middle of things) (i) The epic contains long catalogs of heroes or important characters, focusing on highborn kings and great warriors rather than peasants and commoners. The term epic applies most accurately to classical Greek texts like the Iliad and the Odyssey. However, some critics have applied the term more loosely. The AngloSaxon poem Beowulf has also been called an epic of Anglo-Saxon culture, Milton's Paradise Lost has been seen as an epic of Christian culture, and Shakespeare's various History Plays have been collectively called an epic of Renaissance Britain. Other examples include Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered and the anonymous Epic of Gilgamesh, which is the oldest example known. 12. Epic hero: the main character in an epic poem – typically one who has incredible strength and embodies the values of his or her culture. For instance, Odysseus is the epic hero in the Greek epic called The Odyssey – in which he embodies the cleverness and fastthinking Greek culture admired. Aeneas is the epic hero in the Roman epic The Aeneid – in which he embodies the patriotism Romans admired. If we stretch the term epic more broadly beyond the strict confines of the Greco-Roman tradition, we might read Beowulf as loosely as an epic hero of Beowulf and Moses as the epic hero of Exodus. 13. Exposition: the part of the plot that introduces the characters, the setting, and the basic situation. 14. Foil: a character who provides a contrast of another character, thus intensifying the impact of that other character. For example, Banquo and Macduff act as foils for the murderous and tyrannical Macbeth. 15. Iambic pentameter: a line of poetry that contains five feet, with each foot consisting of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable: “I wake to sleep and take my waking slow.” 16. Irony: a literary technique used to present surprises, interest, or amusing contradictions. The use of words that mean the opposite of what you really think especially in order to be funny; a situation that is strange or funny because things happen in a way that seems to be the opposite of what you expected. 3 17. Kenning: a form of compounding in Old English, Old Norse, and Germanic poetry. In this poetic device, the poet creates a new compound word or phrase to describe an object or activity. Specifically, this compound uses mixed imagery to describe the properties of the object in indirect, imaginative, or enigmatic ways. The resulting word is somewhat like a riddle since the reader must stop and think for a minute to determine what the object is. Kennings may involve conjoining two types of dissimilar imagery, extended metaphors, or mixed metaphors. Kennings were particularly common in Old English literature and Viking poetry. The most famous example is hron-rade or hwal-rade ("whale-road") as a poetic reference to the sea. Other examples include Thor-Weapon as a reference to a smith's hammer, battle-flame as a reference to the way light shines on swords, gore-cradle for a battlefield filled with motionless bodies, and word-hoard for a person's eloquence. In Njal's Saga we find Old Norse kennings like shield-tester for warrior, or prayer-smithy for a man's heart, or head-anvil for the skull. In Beowulf, we also find Anglo-Saxon banhus ("bone-house") for body, goldwine gumena ("gold-friend of warriors") for a generous prince, beadoleoma ("flashing light") for sword, and beagagifa ("ring-giver") for a lord. 18. Legend: a widely told story about the past that may or may not be based in fact. A legend is a story or narrative that lies somewhere between myth and historical fact and which, as a rule, is about a particular figure or person. It is a traditional narrative often focusing on a specific location or specific historical figure. Like myth, a legend often fills in gaps in historical records. Unlike myths, legends usually do not involve powerful gods or worldaltering supernatural events – though they can to a small degree. Famous examples of legends are the legend of Faust, King Arthur, and Pecos Bill. Often tales that were originally myths about deities can devolve into legends, such as might be the case with several Arthurian legends. 19. Lyric poem: a poem that expresses the observations and feelings of a single speaker. Unlike a narrative poem, it presents an experience as a single effect, but it does not tell a full story. 20. Metafiction: fiction in which the subject of the story is the act or art of storytelling of itself, especially when such material breaks up the illusion of "reality" in a work. An example is Chaucer's narrator in the Canterbury Tales, in which the pilgrim tells the reader to "turn the leaf [page] and choose another tale" if the audience doesn't like naughty stories like the Miller's tale. This command breaks the illusion that Geoffrey is a real person on pilgrimage, calling attention to the fictional qualities of The Canterbury Tales as a physical artifact – a book held in the readers' hands. 21. Meter: a regular pattern of rhythm in poetry; or, a rhythm of accented and unaccented syllables that are organized into patterns, called feet. 22. Paradox: a statement that seems to be contradictory but that actually presents a truth. A statement whose two parts seem contradictory yet make sense with more thought. Christ used paradox in his teaching: "They have ears but hear not." Or in ordinary conversation, we might use a paradox, "Deep down he's really very shallow." Paradox attracts the reader's or the listener's attention and gives emphasis. 23. Pastoral: a literary work that deals with the pleasures of simple, rural life or with escape to a simpler place or time. 4 24. Poetry: one of the three major types, or genres, of literature, the others being prose and drama. Poetry defies simple definition because there is no single characteristic that is found in all poems and not found in all non-poems. Often – but not always – poems are divided into lines and stanzas and employ regular rhythmical patterns, or meters. Types of poetry include narrative (ballads, epics, and metrical romances – like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight), dramatic (monologues and dialogues), lyrics (sonnets, odes, elegies, and love poems), and concrete poetry. 25. Prose: the ordinary form of written language and one of the three major types of literature. Most writing that is not poetry, drama, or song, is considered prose. Prose occurs in two major forms: fiction and nonfiction. 26. Rhyme scheme: the regular pattern of rhyming words in a poem or stanza. To indicate rhyme scheme, assign a different letter to each final sound in the poem or stanza. 27. Romance: a story that presents remote or imaginative incidents rather than ordinary realistic experience. In medieval use, romance or chivalric romance referred to episodic French and German poetry dealing with chivalry and the adventures of knights in warfare as they rescue fair maidens and confront supernatural challenges. Their standard plot involves a single knight seeking to win a scornful lady's favor by undertaking a dangerous quest. Along the way, this knight encounters mysterious hermits, confronts evil blackguards and brigands, slays monsters and dragons, competes anonymously in tournaments, and suffers from wounds, starvation, deprivation, and exposure in the wilderness. He may incidentally save a few extra villages and pretty maidens along the way before finishing his primary task. (This is why scholars say romances are episodic – the plot can be stretched or contracted so the author can insert or remove any number of small, short adventures along the hero's way to the larger quest.) 28. Soliloquy: in a play, it is a long speech made by a character who is alone (or under the impression that he or she is alone) and thus reveals his or her private thoughts and feelings to the audience or reader. 29. Sonnet: a fourteen line lyric poem with a single theme. The Petrarchan or Italian sonnet is divided into two parts, an eight-line octave and s six-line sestet. The octave raises a question, states a problem, or presents a brief narrative, and the sestet answers the question, solves the problem, or comments on the narrative. The Shakespearean or English sonnet has three four-line quatrains plus a concluding two-line couplet. Each of the three quatrains usually explores a different variation of the main theme. Then, the couplet presents a summarizing or concluding statement. 30. Sonnet sequence: a series or group of sonnets written to one person or on one theme.| 31. Symbol: anything tangible that stands for or represents something else. In literature, a word, place, character, or object that means something beyond what it is on a literal level. For instance, consider the stop sign. It is literally a metal octagon painted red with white streaks. However, everyone on American roads will be safer if we understand that this object also represents the act of coming to a complete stop – an idea hard to encompass briefly without some sort of symbolic substitute. An object, a setting, or even a character can represent another more general idea. 5 32. Tragedy: a type of drama or literature that shows the downfall or destruction of a noble or outstanding person, traditionally one who possesses a character weakness called a tragic flaw. Macbeth, one could argue, is a brave and noble figure led astray by ambition (or, by his overactive imagination). The tragic hero, through choice or circumstance, is caught up in a sequence of events that inevitably results in disaster.