Beef Reproduction I

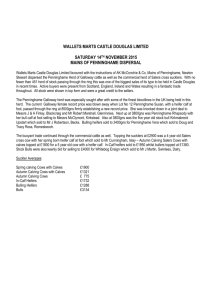

advertisement

Beef Reproduction I, II & III Supplement for CEV #205 - 207 Goal: The student focuses on the efficiency demands of the industry and how these can be met through selective reproduction. Objectives: 1. to select the appropriate breeding stock 2. to understand the male and female reproductive anatomy 3. to appreciate the importance of the male and female germ cells i Beef Reproduction Supplement for CEV #205-207 Introduction In order to meet the goal of the beef industry--providing meat at a reasonable cost--today’s cattle producers have to produce calves as efficiently as possible. The meat packer wants slaughter beef that grades “choice,” but it must have a minimum of external fat. Feeders want calves that will gain the most amount of weight on the least amount of feed. Meeting the needs of these markets is challenging, and the producer’s greatest tools are proper management practices and use of genetics to select production cattle that can meet those market needs. To have a marketable product, cattle producers must first be able to select breeding stock that will produce the highest quality offspring. Once the breeding stock has been selected, the producer must be able to produce these offspring as efficiently as possible. One key to efficient production is the reproductive efficiency of the herd. Despite how well the offspring perform, if the cows do not produce enough calves to pay for themselves, reproductive efficiency is lost. Section I: Beef Reproduction I Selecting Breeding Stock The bull and cow herd are the foundation for calf production, which in turn either become replacement cattle, are sold as a cash crop, or go to the feedlot for fattening as slaughter cattle. Producers should attempt to purchase cattle that are well known to produce the right results. For example, breeds such as Charolais, Limousin, and Simmental are known for producing lean meat, and breeds that are well known for their meat tenderness include Shorthorn, Angus, and Hereford. In order to select the best cattle to raise, the producer must take into account the environment and select cattle which will thrive in the temperature and climate for the region. Selecting Suitable Cattle The type of environment where the cattle will be raised should be considered when selecting breed types. If the cattle are not suited to their particular environment, efficiency will be reduced. Warm-weather Cattle Bos indicus cattle are particularly suited to hot, tropical climates of the southeast and gulf coast as well as the arid desert climates of the southwestern United States. Purebred Bos Indicus (also called Zebu cattle and often improperly called “Brahman” cattle) that are being raised in the United States include Nellore, Gir, 2 Guzerat, Indu-Brazil, Watusi, and the American Brahman. These cattle are extremely hardy and can survive and reproduce on the sparse vegetation of arid climates, and can withstand the insects and humidity of southeastern and gulf coast regions. The offspring of Bos Indicus and Bos Taurus crossed cattle are well-suited for beef production, for the offspring retain the excellent heat/humidity and insect/parasite resistance of the Bos indicus parent and the faster meatproducing ability of the Bos taurus parent. Cool-weather Cattle Continental and British, or Bos taurus breeds, are more adapted to the mid and northern United states where the winters are cold and the summers are mild. These cattle are able to gain weight in feedlot situations without suffering from cold temperatures. These cattle are also often crossed to produce an offspring more suited to their particular environment. If crossed with Bos indicus, the cattle gain thriftiness and insect/disease resistance from their Zebu parent. They are often crossed with other Bos taurus types to blend the best qualities of both breeds. Cross Breeds and Composites Often, the best cattle for a particular area may be crossbred animals that are part Bos indicus and part Bos taurus. These animals are able to withstand the rigors of climates in many parts of the country and efficiently combine the disease resistance and thriftiness of Brahman-influenced breeds with the muscling and high quality meat production of British and Continental breeds. Cross breeding often results in a hybrid vigor called heterosis, which is the amount of improvement in the performance of the crossbred offspring over the average of the purebred parents. Some popular Bos Indicus and Bos Taurus crosses and composites produced in the United States include: Braunbray (Braunvieh x Brahman) Gelbray (Gelbvieh x Brahman) Bralers (Brahman x Salers) Simbrah (Simmental x Brahman) Brangus (Brahman x Angus) Beefmaster (Hereford x Shorthorn x Brahman) Brah-Maine (Brahman x Maine-Anjou) Greyman (Murray Grey x Brahman) Brahmousin (Brahman x Limousin) Sabre (Sussex x Brahman) Braford (Brahman x Hereford) 3 Charbray (Charolais x Brahman/Zebu) Santa Gertrudis (Shorthorn x Zebu) American Breed (Hereford x Milking Shorthorn x Bison x Charolais x Brahman) Barzona (Hereford x Africander x Santa Gertrudis x Angus x Indu-Brazil) Some popular Bos Taurus crosses and composites in the United States include: Salorn (Salers x Texas Longhorn) Black Baldie (Hereford x Angus) Murray Grey (a specific Shorthorn cow x Angus) Senepol (British Red Poll x N’Dama) Chiangus (Chianina x Angus) Chiford (Chianina x Hereford) Beefalo (Bos bison and Bos taurus cross) Bulls Whether you are cross breeding or pure breeding, the bull is the most important individual in the herd. The bull is the source of half the genetics of every calf in the herd. Therefore, it is critical to select the proper sire to complement your cow herd. Areas you should check when selecting bulls are performance records, structural soundness, muscling, temperament, and reproductive soundness. If these areas are adequate, then the bull should undergo a breeding soundness check from your veterinarian. Performance Records An important selection tool is the Sire Summary that is published for most breeds. The most important vital statistic in the Summary is the Expected Progeny Difference (EPD), which predicts the performance of a bull's offspring when compared to the average of the offspring of other bulls in that breed. EPDs are only valid within the breed; they are not used to compare bulls of different breeds. EPDs are calculated for production traits such as growth, maternal ability, calving ease and, in some breeds, carcass traits. Reading EPDs Keep in mind that the EPD number is expressed as units of the trait. For example, weaning weight EPDs are expressed in pounds. The number reflects how the offspring perform relative to the average of the breed. The breed average is always set at zero, so a weaning weight EPD of +5 means the calf is predicted to wean 5 pounds above the average of the breed. The average often is derived from a base year for the breed. As improvements are made through selection, the breed average for the current year may increase, but the base year average remains the same. EPDs are followed by a value that ranges from 0 to 1. This value is the accuracy of the EPD, which tells the reader how certain he or she can be that the offspring 4 will perform as predicted. When more offspring are added to a bull's records, the accuracy increases accordingly. The EPD is calculated from the performance records of the bull's offspring, his performance, and the performance records of parents, grandparents, full siblings and half siblings. Maternal traits are determined from the maternal performances of the mother, grandmother, daughters, sisters and half sisters. These traits are often determined from the weaning weights of these female offspring. For example, records for a bull's maternal ability may actually be the weaning weights of his daughter's offspring. 5 Structural Soundness A bull that is not structurally sound will not have the stamina to travel the pasture and breed all the cows in the herd, or will not be able to support himself when mounting the cows. Either problem will result in cows not getting pregnant and the production efficiency of the herd going down. Check the physical features of the bull. He should have large feet with toes facing forward, free of cracks, curls, and infection. Pasterns should be strong and straight, knees should flex easily, hocks should have a good angle to allow him to walk well and support his weight while breeding. Muscling Another factor affecting fertility and structure is the degree of muscling in the cattle. The main objective of the beef industry is to produce a healthy, appetizing, and saleable product: BEEF. The amount of muscling in an animal determines the percentage of boneless, closely trimmed retail cuts the carcass will yield. This is important to the efficiency of beef production. However, extremes should be avoided. Extremely heavily muscled or double muscled cattle may have structural problems which reduce fertility. On the other hand, light-muscled bulls are often not hardy enough to complete a breeding season without losing some fertility. Temperament In selecting a bull for your herd, select those with a good temperament. Such bulls will eliminate much of the danger factor for the ranch hands involved in tending the herd or the assistants who work with bulls during semen collection. Bulls with good dispositions are also less prone to nervous or challenging behavior, thus reducing the danger factor for other bulls in the herd and reducing injuries to cows during breeding. Reproductive Soundness An infertile bull is useless for production, but a subfertile bull is also detrimental to the herd because the offspring he produces are likely to be subfertile as well. A producer that comes up with several open cows after breeding season will be wise to suspect subfertility as a cause, and he should check out the bull before he culls the cows that didn’t get pregnant. Before purchasing or leasing a bull, or before using your own bull, you should make sure the bull has been checked for reproductive soundness. The examination should include making sure his sheath hangs close to his body, with no prepuce (tip of penis) exposed when it is relaxed, to prevent injuries from brush and vegetation in the pasture. The testicles should be equal in size, firm but not hard, free of lumps and scar tissue, and of adequate size for his breed and age. Brahman breeds generally have testes of smaller circumference (up to 4 inches smaller) than other breeds. 6 General measurements of the scrotum circumference for age should fall within this range: 12-14 months 15-20 months 21-30 months 31+ months 30-34 cm 31-36 cm 32-38 cm 34-39 cm Breeding Soundness A bull that has passed the tests for structural and reproductive soundness, muscling, and temperament is then a good candidate for breeding soundness testing by a veterinarian. The doctor will give the bull an over-all exam, palpate the accessory sex glands to check for abnormalities, measure the scrotum circumference for record keeping, and take a semen sample for analysis. If all else comes out OK and the semen sample is good, you have yourself a production quality bull. Cows and Heifers Production heifers should be selected from cows that calve early and raise the largest calves. Ideally, the heifer will herself have a high weaning weight but then keep a low mature weight so maintenance costs are kept as low as possible. Heifers should also be evaluated for structural soundness, muscling, and temperament. Structural Soundness Evaluate cows and heifers for their general physical soundness and conformation, remembering that half of the calf’s genetics will come from the mother. Heavily muscled cows may have difficulty in calving; light-muscled cows may not be able to nutritionally and physically support a calf until weaning. Udder development, both in number of teats and their placement, is important in productive cows. Breeding Heifers After weaning, the heifers should be fed a ration that will allow them to reach approximately 65% of their mature weight by 14 or 15 months of age. At this size and age, most heifers should experience heat, or the first estrus. Heifers should be bred by 15 months of age to calve at two years of age. Heifers that calve at two years will average one more calf in their lifetime than heifers that do not calve until three years of age. Some producers believe dystocia, or calving 7 difficulty, is lower in heifers that first calve at three years. However, in most cases the reduction in dystocia does not offset the productivity lost by averaging one less calf than heifers which calve as two-year-olds. The best way to reduce calving difficulty is to use bulls with a low birth weight EPD. Smaller calves cause much less distress than a large calf, particularly in first calf heifers. Review of Beef Reproduction I The primary goal of the beef industry is to provide quality meat at a reasonable price; that means cattle must be produced as efficiently as possible to keep costs down. Selecting good breeding stock is essential to this goal. Producers should choose breeds that do well in their environment, and they should give special attention to selection of their production bull or bulls and to their production cows and heifers. Bulls should be structurally sound with good conformation, heavily muscled but not extreme, and of good temperament. The bull must be fertile and should have a good performance record, as shown through excellent EPD values found in the sire summary. Production cows should be structurally sound with good conformation, sturdily muscled but not extreme, with excellent udder development and a good temperament. Heifers should be chosen from cows that calve early and raise large calves. Heifers should be fed well so they can be bred at about 15 months of age. Calving difficulties in young heifers can be reduced by using bulls with a low birth weight EPD. Section II: Beef Reproduction II Reproductive Efficiency of the Cow Herd The single most important trait of the herd is the number of calves weaned per cow exposed to breeding. Many important technologies have been developed to enhance the reproductive efficiency of the cow herd and assist in genetic improvement of the herd. These technologies include: estrous synchronization, estrus detection, frozen semen and frozen embryos, artificial insemination, embryo transfer, and ultrasound determination of pregnancy. Estrus Synchronization Estrus synchronization is an important factor in managing the cow herd. If the cows in a herd are in estrus at the same time, the labor required to have a successful artificial insemination program is greatly reduced. Cows can all be inseminated on the same day. This allows the herd to be worked only once rather than several times to breed all the cows. Synchronized estrus and insemination leads to a shorter calving season. All the cows are bred on the 8 same day so they should all calve within several days of one another. This also gives the producer a uniform weight calf crop at weaning time. An added benefit of synchronization is to customize the calving operation to fit the differing needs of first-calf heifers and mature cows. Often, producers bring all the heifers into estrus about 30 days before the cows, then use artificial insemination with the semen from a bull with an EPD for low birth weight to reduce calving difficulties. By synchronizing and inseminating the cows at a later time, heifers should calve first, allowing the producer to give the first-time mothers more care and medical attention. Also, the heifers’ calves, which tend to have a lower birth weight due to first-time calving and use of low weight bull semen, will have a chance to catch up in weight to the cows’ calves, thus allowing a more uniform weight calf crop going to market or being placed in the herd. This staggered breeding also allows heifers an extra thirty days for postdelivery healing before being rebred with the rest of the cows for the next season. Synchronization can be accomplished with hormone injections with Syncro-Mate-B, Lutalyse, Bovilene, and Estrumate. Estrus can also be induced through progesterone implants. Estrus Detection Estrus detection is an important factor in breeding programs that utilize artificial insemination, superovulation, and embryo transfer. Estrus can be detected by skilled producers through observing behavior. A swollen vulva, discharge, seeking out the bull, and standing for mating (even by other cows) are symptoms of estrus in cows, also called standing heat. If a bull or the young bulls in the herd are persistently following a cow, she may be in very early or very late stages of estrus. Another indication is the “flehman response” in which a bull raises his head and curls his upper lip upon sniffing the cow’s vulva or putting his nose into the cow’s urine stream. The herd should be observed every morning and evening to accurately detect estrus. Estrus Detection Aids There are several heat detection aids available for use when the herd cannot be observed regularly throughout the day. Both depend on the use of marker animals to indicate that the cow experiencing estrus has been mounted. A marker animal is either an androgenized cow (one treated with male hormones so she acts sexually like a bull) or a gomer or teaser bull (a bull surgically altered, allowing him to mount the cow but not penetrate and cause pregnancy). The chinball marker is an estrus detection aid that is attached to the marker animal and leaves a trace of paint on the back of the cow when she is mounted. KaMaR pressure patches are applied to the rumps of cows. These patches release colored ink when they are activated by the pressure of the marker animal mounting the cow. Superovulation 9 Superovulation is accomplished by injecting Follicle Stimulating Hormone, (FSH) into the cows. In females during the normal progression of pregnancy, this hormone causes the development of a single follicle that ruptures and releases the egg into the oviduct. When given in large doses, FSH causes multiple follicles to develop and release eggs. This results in the recovery of many eggs that can be fertilized or frozen and placed into cows as surrogate mothers. Superovulation allows superior females to produce eggs, which are then usually inseminated and allowed to grow into embryos before being placed in the recipient cows in a process called embryo transfer. Embryo Transfer Embryo transfer requires a combination of sychronized estrus, superovulation, and artificial insemination. The donor cow and the recipient cow must have synchronized estrus. The donor cow is superovulated, then artificially inseminated. Approximately 6 days after estrus the embryos are flushed out, evaluated, and placed into the uterus of the recipient cow for gestation. If no recipient cow is available, the embryos may be frozen and stored or shipped. Embryo transfer allows several calves from a superior female to be born in the same year, which expedites progeny testing of females. Before embryo transfer, progeny testing in females was virtually impossible. The accuracy of a progeny test depends on the number of offspring an individual has produced. The individual should have at least 10 offspring to provide an accurate test. A bull may easily sire the necessary number in a single year, but a cow may not be able to naturally produce that many calves in her lifetime. Freezing and storing embryos or semen has facilitated the exportation/importation of superior quality cattle because although bulls and calves face quarantine, testing, and holding periods, there are no such restrictions on frozen products. Another advantage to collecting frozen embryos and semen is that the products can be easily stored and shipped, and the products can be used long after they are collected. Artificial Insemination Artificial insemination allows producers to breed their cows with superior bulls that would normally be unavailable to them or would be too expensive for them to use. The semen is collected from the bull in an artificial vagina and then evaluated for motility (movement) and morphology (physical structure). The sperm cells should have a rapid forward motion and should be free of deformities such as two heads or tails, missing heads or tails, misshapen heads, or curly tails. If the semen has adequate concentration of sperm cells and the cells are normal and alive, the semen is deemed acceptable and may be diluted with an extender fluid and placed into “straws,” each of which will contain approximately 40 million sperm cells. The straws are coded with information, cooled down, and then frozen for storage or transportation. 10 After the semen is thawed, it should be checked under microscope to make sure that the semen has kept at least 25% motility. Then, the straw is placed into an insemination gun, the long extension of the gun is passed through the cow’s cervix (which is relaxed during estrus), and the semen is deposited in the body of the uterus. Pregnancy Diagnosis If a cow has not returned to heat within 21days after insemination, she can be suspected of having conceived. Because other problems can mimic pregnancy (such as ovarian cysts, a silent heat, or not noticing the cow came into heat), cows are considered pregnant if they don’t come into heat within 60 days, or three estrus cycles. In herds that have two calving times, the cow that did not conceive may be given a second chance to do so in the second breeding period. A cow that misses conception twice will probably be culled from the herd. If the cows were bred through artificial insemination, the whole herd can be checked at one time, a good time-saving management procedure. Producers use the previous calving records for the cow, the dates of exposure to breeding, and pregnancy diagnosis results to help estimate the calving date. Methods of Pregnancy Determination Pregnancy diagnosis is most often performed with one of two methods: rectal palpation or ultrasound. One advantage of rectal palpation is reduced cost, but accuracy requires both skill and experience. The technician can estimate the age and development status of the fetus through reaching through the rectum and feeling the head, legs, and position of the fetus within the uterus, and the size of the codiledients (nutrient sacks inside the uterus) that nourish the calf. Palpation is usually best used in advanced pregnancies. Ultrasound imaging may detect an early pregnancy that would be missed during palpation because of the tiny size of the fetus. Ultrasound is able to tell if the embryo is alive (can see heart beating), and is less likely to cause pregnancy problems or abortions because it doesn’t physically disturb the embryo. Review of Beef Reproduction II In order to make the best use of available technologies, cattlemen must understand the basic biological processes involved in estrus and the estrus cycle. The goal is for 100% of the cows to deliver a healthy calf each year. Cattle producers may choose to use natural breeding using their own or leasing a quality production bull, or one of the newer reproduction enhancement technologies to ensure pregnancies. These technologies include estrus synchonization, methods for estrus detection, artificial insemination, superovulation, embryo transfer, and freezing and storage 11 of semen and embryos. Producers can use ultrasound to detect early pregnancies, or use rectal palpation after the first trimester to physically confirm the fetus. Section III: Beef Reproduction III Good management practices are the key to making a profit in the cattle business. Cattle must be healthy so that cows produce quality calves and bulls remain fertile; heifers must be feed well and cared for so they reach a desired weight for breeding; calves must be given good attention so they grow healthy and strong. Health of the Herd When a cow is open (did not conceive), it is often assumed that the cow has a fertility problem. However, the reduced calf crop may also be due to a sub-fertile bull, inadequate nutrition in the herd, or even a disease outbreak that causes abortion in the cows. The health of the herd is taken care of through good nutrition, maintaining good body condition, and use of vaccinations to prevent diseases. Nutrition The herd should be given the highest quality food available, whether in forage or supplement feed. Here is some useful information regarding nutrition in beef cattle: 50% to 60% of the cost of raising cattle is feed. In young cattle, half of feed goes to maintenance, half to gain. Steers consume more feed than heifers; heifers are often over-fattened. Larger exotic breeds gain faster than British breeds but must be carried to a heavier weight to grade choice (need about 15% more feed). Brood cows and growing cattle need 1-3 lbs. protein/day. Protein requirements are low in early and middle gestation (1.5 to 1.7 lbs/day), but increase substantially before/after calving and during lactation (to 2.5 to 3 lbs/day). Water needs of cattle run 1 gal/100 lb. body weight in winter (twice that in summer). Lactating cows need twice as much water as do dry cows. The major vitamins of concern in beef cattle are A, D, and E. The major minerals of concern are copper, zinc, manganese, iodine/cobalt, and selenium. Breeding cattle require phosphorus in their diet (phosphorus should never be higher than the calcium level). Reduced cow fertility can be caused by low amounts of selenium, phosphorus, or copper and zinc. Heifers should be fed to reach a target weight of between 650 and 750 pounds, or 65% of their mature size, by 15 months of age. This allows them to come into estrus and be bred to calve at two years of age. Heifers should be bred 30 days before mature cows and fed separately from cows during gestation to ensure 12 they receive adequate nutrition because the heifers are themselves still growing, plus supporting a calf, and mature cows tend to push heifers away from the best food. Nutritional Needs During Pregnancy Cows and heifers need good nutrition throughout gestation, and up to twice as much dietary energy from feed 45-60 days prior to calving and after calving and during lactation. The cow must provide nutrition to the growing fetus through nutritional nodes called codiledients which grow in the uterus along with the calf. Cows that don’t receive enough protein in the last 60 days of pregnancy stand a greater chance of delivering calves born with “weak calf syndrome.” Cows also need good nutrition—up to twice as much as normal feed, including water--during lactation so they can supply good milk to the growing calf and in order to be in good condition to rebreed on time. Body Condition The body condition scale ranges from 1 to 9, with 1 being extremely emaciated and 9 being extremely obese. A score of 5 is the best and a score of 4 or 6 is acceptable; beyond these scores reproductive efficiency may be compromised. Body condition is important in all members of the production herd. The bull must have adequate condition to last through the breeding season. However, if the bull is too fat, he may be lazy and sluggish and may not cover all the cows. Cows also should have adequate condition to support a calf to weaning. The cow will use her fat stores to provide milk for the calf. If she has no fat stores, her reproductive performance may decrease. The same is true of cows that are too fat; they often experience reduced conception, and if they do become pregnant, they may have difficulty calving. Good body condition can be maintained by feeding the best quality food, whether forage or feedlot grains or any combination, that is tested so the rancher can include adequate amounts of vitamins and mineral supplements if they are needed. Pastures should not be overstocked or overgrazed. Care should be taken that mature cows don’t push pregnant heifers away from the best food. Protein supplements such as soybean meal, urea, ammonia, brewer’s grains, cottonseed meal should be kept high quality until calves reach at least 600 pounds; after that, the source of protein is not as important, and cheaper forms, such as urea, can be used. Vaccinations The health of the production herd can be safeguarded by protecting them against infectious diseases. The cow herd should be vaccinated against diseases such as Brucellosis, Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis IBR), Bovine Virus Diarrhea (BVD), Leptospirosis, and Vibriosis, which can all cause reduced fertility and spontaneous abortion. Confer with your veterinarian for the protection most needed in your area of the country. 13 Cows should be vaccinated 6 to 10 weeks before delivery so the protection is passed on to their calves through the first milk—their colostrum. Breeding Program Reproductive efficiency is determined by the number of calves weaned per cow that were exposed to breeding. The goal is 100% of cows and heifers pregnant each year. A cow that does not conceive within two breeding opportunities is usually culled. Producers can reach closest to the reproductive efficiency goal by paying strict attention to management practices that increase the fertility of the bull and through using quality replacement heifers. Reduced Reproduction If there are several cows that remain open, the producer should first check the fertility level of the bull. If the bull checks out OK, then producers should check the nutritional levels of the cattle to be sure their diets include sufficient amounts of phosphorus, zinc, and manganese because feeds and forage low in these minerals can cause reduced fertility. Also check pastures or range lands to be sure there are no poisonous plants or plants which, at certain levels of ingestion, can cause spontaneous abortion, because a few of these “open” cows may actually have aborted early in pregnancy. If you have a cow that comes up open, yet you are pretty sure she conceived, she may have had an embryonic death. Embryonic death rate is fairly high, from 10 to 20% of all pregnancies. In this case, the egg was fertilized and an embryo created, but the embryo did not attach to or implant in the uterine wall. If the embryonic death occurred in the first two or three weeks of fertilization, the cow will most likely return to a normal estrus cycle. If the death occurs later, then the cow will seem to have an extended heat cycle, when she had actually been pregnant. Bulls Fertility in the bull is critical to the success of any breeding program. If the bull is infertile, the quality of the cows won't matter. When a cow is open, it is often assumed that the cow has a fertility problem. However, the reduced calf crop may be due to a subfertile bull. Fertility in bulls can be influenced by the weather, age of the bull, illness, structural soundness, and nutrition. Around four years of age, fertility in the bull tends to peak. Many bulls are adequately fertile until 7 or more years of age, but age tends to affect fertility. Nutrition is also important to the fertility of bulls, and quality of the feed is as important as the quantity. Many producers have found that a deficiency in vitamins and minerals can cause reduced fertility in their herds. Therefore, they supplement the diet with mineral and vitamin blocks or fortified feeds. Structural soundness of the bull is important because he must be able to travel the distances necessary to cover all cows. If a bull is expected to cover too many cows, the bull may not be able to locate all the cows that are in heat at one 14 particular time, or he may be overworked and suffer a low sperm count. Extremely hot weather or a prolonged fever may reduce the sperm count of a bull for 6 to 10 weeks. The testes must remain about 4 to 5 degrees below body temperature to produce sperm properly. The loss of sperm production will cause the bull to be infertile for as long as the temperature stress lasts plus the amount of time it takes for new sperm cells to be produced and mature. A breeding soundness exam will tell the producer if the bull is fertile and able to breed the cows in the herd. Replacement Heifers First-calf heifers are bred 30 days before mature cows so they calve earlier and have more time to heal after calving; then they are rebred at the same time as the rest of the cow herd. The average gestation of cattle is 283 days and it takes approximately 45 days to heal after calving. That leaves 37 days in which to rebreed the cow so she calves every 365 days. This extra time gives the heifers 67 days to become pregnant again and calve with the rest of the herd the next year. The best way to decrease calving difficulty is to breed heifers to bulls with a low birth weight EPD. A smaller calf will be less likely to cause distress, provided that the presentation of the calf is normal. Calving Many cattle producers give their pregnant cows additional vaccinations about 60 days before delivery to assure that maximum protection is passed on to the newborn. Near the projected calving date, heifers should be observed closely. Experienced persons should be ready to assist if the heifer needs help, and they should know when to call for medical assistance when it is needed. Cows about to deliver will look for a spot away from the herd, and usually mature cows can handle the delivery process by themselves. Signs that Parturition is Near When a cow is nearing delivery time, the udder will be enlarged, with possible dripping of colostrum; the hindquarters will be quite droopy-looking as the pelvic ligaments relax; the mucous plug will be expelled, leaving a slight discharge seepage. If the cow is birthing in a stall, provide clean straw bedding shavings may be too small and can get into the calf’s lungs. Generally, leave the cow alone, but be nearby if she needs help. Parturition Calving progresses in three stages: labor, delivery, and expulsion of the fetal membranes. Labor The preparatory stage, or labor, is marked by uterine contractions about every 15 minutes and dilation of the cervix. This stage may last up to 24 hours, but usually ranges between 2 and 6 hours. During this time, the cow may get up and lay down repeatedly, stand with her tail up and her back 15 arched, and kick at her stomach. This stage ends when the calf moves into the birth canal and the water bag ruptures. Delivery Contractions come every two minutes and the cow’s abdominal muscles begin to actively push the calf from the birth canal. The front feet are delivered first, with the head resting on top of the legs. The remainder of the body will then be quickly pushed out. If only one leg appears, or if the head seems to be bent backward, you may be able to reposition the calf so that delivery can proceed. If it is still intact, tear the sac from around the calf’s head, but do not cut the umbilical cord. The cow and calf will break the cord themselves as they move around. Delivery may last up to 4 hours without harm to the calf if the umbilical cord is still intact. If 3 or more hours pass with no apparent progress, the cow may be experiencing dystocia, and assistance might be needed. Dystocia is a complication in delivery caused by pelvic problems or muscle contraction problems (maternal dystocia) or malpositions or malformations of the fetus (fetal dystocia). The leading cause for dystocia in a heifer during delivery is a calf that is too large to pass through the pelvic opening. That is why it is best to use low-birth weight bulls for firstcalf heifers. If pulling the calf as the cow has contractions is not effective within a half hour, professional help should be sought. It may be necessary to perform a Caesarian section to get the calf out. Expulsion of the fetal membranes The third stage, expulsion of the fetal membranes, should be complete within 8 to 12 hours or the placenta may cause an infection. The placenta should be examined to ensure that all of it has passed from the cow. If the placenta is not delivered, do not pull the afterbirth from the uterus or you may cause damage. Get medical help to increase the cow’s uterine contractions so she can expel all the afterbirth. Retained placenta can be caused by low selenium, low vitamin A, or low amounts of copper or iodine in the diet. Post-Delivery Care of the Cow Make sure the cow was not injured during the delivery process. Many ranchers give cows a tetanus antitoxin injection to help protect against infection while the cow is in the recovery period. Give the cow increased amounts of quality food and water so she can produce the milk needed to support the growing calf. During the healing period, check the cow for post-delivery problems. Although not as common in beef cows, she may also need to be checked for inflammation of the uterus (metritis). Check on the cow during the next few days to make sure 16 she doesn’t develop Pyometra, a problem that occurs after birthing when the cervix closes, preventing drainage of infected material from the uterus. Pyometra can lead to sterility. Post-Delivery Care of the Calf After the calf is delivered, it should be checked to be sure that it is able to breathe. Clear air passageways of any mucous if necessary. If the calf is not breathing, try tickling the inside of the nostrils with a feather or finger to cause a sneeze or intake of air. If the lungs are filled with fluid, lift the calf by the hind legs to try to drain the lungs. If the calf still does not breath, try lifting and lowering the front legs to draw air into the lungs, much like CPR in humans. Treat the navel with a solution of iodine or similar disinfectant to prevent infection. Within the hour, the calf should be able to stand and will begin searching for his or her first meal. The calf should nurse 3 to 6 pints of the first milk, called colostrum, which contains Vitamin E which the calf needs and antibodies to the diseases to which the cow has been exposed. After 24 hours, the antibodies are no longer absorbed, so if the calf will not suckle, try to get the calf to drink milk with colostrum from a bottle. Milk with colostrum can be captured from the mother before calving and frozen to be used in such cases, it can be captured from a cow that has also just given birth and whose calf is suckling well, or it can sometimes be purchased in frozen or powder form. Review of Beef Reproduction III There are many factors affecting the reproduction in a cow herd. Good management practices are the key to improving the efficiency and productivity of the herd. Cattle producers should make sure their cattle are vaccinated against diseases which could reduce fertility or cause spontaneous abortion in cattle. The cattle should be fed well, with supplements if needed, to maintain a good body condition and prime reproductive ability. Cows and heifers should receive good nutrition during pregnancy so they can support the growing calf. Heifers should receive extra nutrition because they are not only supporting a growing calf, they are still growing as well. When the time comes for rebreeding, do not overfeed the still-lactating mothers, because obesity can cause reduced conception and birthing problems with the next calf. Heifers are usually bred 30 days before mature cows so they can be helped during delivery and so they have an extra 30 days to heal before their next rebreeding along with the other cows after calving. Dystocia in heifers can be reduced by using bulls with low birth-weight EPDs. Cows will usually take care of parturition themselves, but you should be nearby in 17 case difficulties arise. If you do have to give assistance, make sure you, any equipment, and the vulva of the cow are kept as sanitary as possible to reduce the risk of infection. Make sure the cow expels the entire placenta so it doesn’t cause uterus infections, which may in turn cause permanent sterility. Make sure the calf is uninjured, breathing and drinking colostrum within the first hours and the next two days. The colostrum gives the calf protection against diseases and calves are born with low amounts of vitamin E, a vitamin found in the colostrum. Anatomy Male Testes The testes are the site of sperm production. The testes are also responsible for secretion of the male hormone testosterone. Testosterone controls the expression of the secondary sex characteristics in bulls (such as the crest, or hump and deep voice). Scrotum The scrotum is a fleshy sack surrounding the testes. The scrotum provides protection from the outside environment. The testes are most productive at a temperature of 4 to 5 degrees below the normal body temperature of the bull. The cremaster muscle in the scrotum will contract to bring the testes closer to the bull's body when outside temperatures are cold. During hot weather the muscle will relax to allow heat to escape from the testes so that the temperature does not rise to levels that would compromise sperm production. If the bull has a prolonged fever the sperm production of the bull may suffer. Epididymis Duct leading away from the testis to the vas deferens. The epididymis is the site of storage and maturation of the sperm cells. Vas deferens Passage for sperm from the epididymis to the urethra in the pelvic area. Urethra (not shown) The single duct that leads from the vas deferens, near the accessory sex glands, to the end of the penis. Serves as an excretory duct for semen and urine. Accessory sex glands 18 Provide fluids essential for formation of the semen and for assuring optimum motility and fertility of the sperm. The accessory glands include the bulb urethral, prostate and vesicular glands. The fluids contribute fructose, a source of energy for the sperm cells. The fluids also serve as a buffer to protect the sperm cells from the slightly acidic environment of the vagina. Penis Male organ of copulation. Sigmoid flexure S-shaped bend in penis that allows the penis to be drawn completely into the body. Straightens during copulation. Retractor penis muscles Smooth muscles that relax and allow the sigmoid flexure to straighten and the penis to be exposed. Sheath Loose skin that encloses the free end of the penis. Anatomy Female Ovary Essential organ of reproduction in the female. The ovary produces the hormone estrogen, which is responsible for the expression of female secondary sex characteristics (such as the development of mammary tissue). The ovary also produces progesterone (via the corpus luteum) during mid- estrous cycle and pregnancy. The ovum or egg is released from the ovary in a process called ovulation. Oviduct Tubular structure that serves as the passageway for the egg after ovulation. The oviduct is also the site of fertilization. Fimbria Funnel-shaped opening of the oviduct that covers the ovary and catches the egg at the time of ovulation and funnels it into the oviduct. Uterus Site of fetal growth and development. Also called the womb. Consists of the uterine body and the uterine horns. The embryo will attach or implant itself to the wall of the uterine horn approximately 6 days after fertilization. 19 Cervix The cervix is a muscular ring that serves to close off the uterus from debris or bacterial pathogens that may cause harm to the fetus. The cervix relaxes during estrus to allow passage of the sperm into the uterus after breeding. Vagina The area where copulation occurs. The semen is deposited in the vagina and travels through the cervix and into the uterus and oviduct. Vulva The vulva is the external portion of the female reproductive tract. Consists of labia and clitoris. Clitoris The clitoris is homologous to the penis in the male; that is to say, they arise from the same embryonic tissues. 20 Vocabulary Atresia: absence or disappearance of an anatomical part (such as an ovarian follicle) by degeneration. Conceptus: the fertilized egg, embryo or fetus. Estrous cycle: regular pattern of changes a body goes through from one estrus to the next(approximately 21 days in the cow); may be interrupted by pregnancy or manipulated through hormone treatment. Estrus: the period of time when the female is receptive to breeding and is able to conceive; lasts 6-14 hours and occurs approximately every 21 days. Gametes: male or female germ cells; sperm or egg. Gestation: carrying of the young in the uterus; pregnancy. Morphology: the physical structure of the sperm cell. Mortality: the percent of dead sperm in a sample. Motility: the ability of the sperm cell to make rapid forward progress. Parturition: the act or process of giving birth to offspring. Perivitelline space: the space between the vitelline membrane and the zone pellucida. Vesicle: fluid filled space or pocket. Vitelline membrane: the cell membrane of the ovum. Zona pellucida: the heavy membrane that surrounds the ovum after ovulation. 21