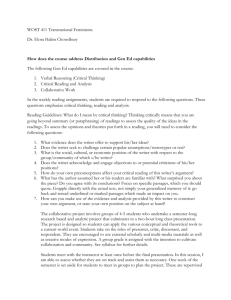

South African Autobiographies

advertisement

ANTIDOTE FOR GLOBAL FEMINIST GAPS AS ENCODED IN SINDIWE MAGONA’S BLACK SOUTH AFRICAN AUTOBIOGRAPHIES Lesibana Rafapa University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa Corresponding author: Lesibana Rafapa. University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. E-mail: rafaplj@ unisa.ac.za. 141 142 ABSTRACT The relatively new black woman South African writer Sindiwe Magona’s autobiographies To My Children’s Children (1990) and Mother to Mother (1998) urge the agency of oppressed black South African women in a nuanced manner. That she portrays female characters from a characteristically feminist perspective framed normatively within a milieu in which women are confronted by and confront challenges in a racialized and gendered context should not misidentify her as a discursively indistinct feminist writer. This chapter argues that Magona’s category of writings epitomized mostly in her two major works hinges on female protagonists reinventing themselves in an exploitative and discriminatory atmosphere not in a way compatible with what are conventionally acknowledged as the types and evolutionary features of dominant feminist theory. I analyze Magona’s works with the objective of illustrating how they are anchored in fresh explanations of aspects of black south African cultures as mindful of and sympathetic to the social position of women. By a close look at Magona’s work and some aspects of black South African cultures constituting the fabric of her art, I engage earlier feminist interpretations reached by Magona analysts through what I demonstrate to be distorting lenses that deny self-description through (mis)representation. I make a distinction between Magona’s individual character depiction dwelling on disposition coalescing into what may be understood as individual trait unfolding within a specific cultural matrix, as opposed to a kind of characterization identifiable as metonymically symbolic of communal ethos. The study seeks to highlight how discourse in Magona’s novels contributes to a theory of feminism accommodative of social vantage points hitherto repressed in dominant feminist discourse tilted towards the more powerful centre. MAGONA’S DEVELOPMENT OF A WOMANIST REFRACTED VOICE WITHIN GLOBAL POLYVOCALITY In this chapter I consider how in her autobiographies To My Children’s Children (1990) and Mother to Mother (1998) the black South African woman writer Sindiwe Magona displays a profound critique of dominant feminist theory as well as apply it to the discourse of her narratives in a distinctive manner deserving of critical attention. While Magona’s relative under-appreciation as a writer of fiction can be ascribed to the fact that as recently as 1999 she could be described as “a recent practitioner of the novel form … not that widely known outside South Africa” (Boehmer 1999:159, 160), the niche she has now carved for herself warrants more dedicated critical attention. Due to the autobiographical element of her fiction (see Daymond 2002:331; Masemola 2010:117), I integrate my scrutiny of Magona’s novels or autobiographies within what I assert as her real life discursive progression within the feminist conceptual framework the distinctive inflection of which I am pursuing in this study. A character like Joyce in Magona’s 143 1991 short story collection Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night incarnates some aspect of Magona’s theoretical immersion in the former’s fictionalized view that “a feminist perspective in South Africa is inhibited by racism” (Magona 1991:59). Even a critic such as Loflin (1990:112) does shed light on this kind of characterization, albeit from a historically periodising vantage point paying scant attention to what may be described as the short narratives’ dialectical theoretical matrix of feminism. Magona’s life journey testifies that she has been exposed to and influenced by feminist theory in interesting ways this chapter seeks to outline. Intellectually equipped with academic and professional qualifications including degrees from Colombia University, with an experience of working for the United Nations in New York and living there for twenty three years, it cannot make sense that she has not grappled with feminist ideas forming part of the global intellectual context at least from the time “issues like race and class … were an integral part of the feminism of the 1960s and 1970s” (Mann and Huffman 2005:60). One feature of Magona’s ‘moulding’ by feminist theory is her appropriation of the 1980s postcolonial theoretical feature of “global feminism.” According to Mann and Huffman (2005:66), this tenet of feminism highlights “relations between local and global processes affect[ing] women in different social locations across the globe.” I intend to include this criterion in my scrutiny of the discourse of Magona’s selected novels. In addition to testing the discourse of Magona’s narratives against major feminist postcolonial theoretical orientations, I shall probe evidence from them of feminist postmodernist and post-structuralist views of identity as “simply a construct of language, discourse, and cultural practices” (Mann and Huffman 2005:63). In this way I should show how Magona’s influence by feminist theory bears some correlation with its evolving tenets across the ages. As further testimony of Magona’s comprehensiveness in subsuming feminism in order to consolidate her own trope of womanist social commentary, I explore also how the discourse of Magona’s fiction points to a space in her feminist evolution identifiable with 1970s “third wave” feminists in their refinement of second wave tendencies to “factionalize” women unified internally by a “sisterhood” that yet ended up treating “oppressions as separate and distinct” and hierarchisizing oppressions by treating “one form as more fundamental than another” (Mann and Huffman 2005: 59). In keeping with the global evolution of feminist theory , there is evidence in Magona’s fiction of what may be seen as her commonality with a section of the 1970s “third wave” or new generation feminists is their moving of “subjugated voices from the margins to the centre, thus decentering dominant discourse” (Mann and Huffman 2005:65). Magona’s critical identification with the intersectional position of the second wave counter-faction of feminist women of colour who viewed “identity politics as the key to liberation” (Mann and Huffman 2005:58), in reaction to what may be described as dominant white women’s pushing of black women from the centre of then dominant feminist theory strongly taking root in America, is further evidence of her familiarity with the different streams of feminism as the theory developed across geographical space. Intersectional thinking, according to Mann and Huffman (2005:58), arose “in the United States … from within the second wave … [sharing] a focus on difference … that embraced identity politics as the key to liberation”, while one faction co-existing with it “saw freedom in resistance to identity.” Intersectional views negated those of the second wave of American feminists for “alleged essentialism, white solipsism, and failure to adequately address the simultaneous and multiple oppressions” of women across race and class (Mann and Huffman 2005:58). Such a strand of third wave 144 feminists was later “exemplified by postmodernist and post-structuralist feminists who critically questioned the notion of coherent identities and viewed freedom as resistance to categorization or identity,” as Mann and Huffman (2005:58) explain. I argue that Magona’s novels display a typically feminist defiance of binary exclusivism, in both common and unique ways setting apart both her literary project and brand of feminism. As I analyse the three novels by mapping the evolution of global feminism onto Magona’s progressive immersion in the theory, I illustrate how close she is to some womanist, intersectional and polyvocal problematisation of what would otherwise be a regurgitated affirmation of dominant discourse within feminism. As Mann and Huffman (2005:65) explain, polyvocality embraces the view that “No one view is inherently superior to another and any claim to having a clear view of the truth is simply a masternarrative – a partial perspective that assumes dominance and privilege.” I argue that a polyvocal stance frames Magona’s discourse in the two novels, identifiable with the manner in which, according to Mann and Huffman (2005:63-64,) the common epistemological ground joining intersectionality with postmodernism and post-structuralism is the way in which exponents of the crisscrossing streams “call for … more localized mini-narratives to give voice to the multiple realities that arise from diverse social locations.” The womanism I will use data collected from Magona’s novels to trace, is one Alice Walker sees lived by a “communal mother … who is committed to the integrity, survival and wholeness of entire peoples due to her sense of self and her love for her culture” (Mehta 2000:397). AGENCY URGED FOR BLACK SOUTH AFRICANS WITHIN A COMPLACENT APARTHEID NATION: TO MY CHILDREN’S CHILDREN AND MAGONA’S WOMANIST DISCOURSE Magona’s autobiography To my Children’s Children (1990) opens with an implied interpretation by the South African woman writer herself of her work as an attempt at performing a written preservation of the black South Africans’ socio-political history, which normally would have been transmitted verbally for the reason that theirs “is an oral tradition” (1). She tells not only her own life story as she describes what it was like “living in the 1940s onwards … in the times of your great, grandmother, me” (1). Simultaneously she hints at the entire narrative carrying out an explication of the history of a people, by making it clear that the autobiography details how “Heavy, indeed, was the yoke that black people bore” due to apartheid conditions created by a patriarchal and racist white rule in which “the white man … had set himself up as their god” (1). Her anti-racist stand is reinforced when the symbol of patriarchy is expanded to include blackness, as in her authorial statement concerning her authoritarian father whose sense of “being powerful” would never leave her (2). That Magona’s conception of feminism includes the view that “macroeconomic policies have gendered effects” (Berik et al. 2009:3) is borne out when right at the opening of the autobiography she conjures an atmosphere of economic domination in phrases like “pounds, shillings, and pennies” and “rands and cents” (1). One more crucial element of Magona’s discourse in this long narrative is her projection of a religious pluralist ideal, by referring to white people imposing themselves as the” god” of black South Africans under apartheid. 145 Among the defining features of the cosmology of the black South Africans living in the village of Gungululu with the protagonist, are spiritualities symbolized by the phrases “Ootikoloshe, the little people, and izithunzela, the zombies” (10), “believed thunder was God speaking” (11), “spill beer on the ground before drinking that the ancestors may partake thereof” (12) and “suffered through at church” (15). By acknowledging the presence of western Christian churches among the black villagers, Magona feministically lets go of what would otherwise be an ethnocentric view of spirituality. After earlier referring to whites imagining themselves as the “god” of oppressed black South Africans, her childhood memory of lighting invokes a hybrid conception of the natural phenomenon as “God”, speaking – this time a deity spelt with capital “G”. However, the narrator’s confession that during her childhood she found Sunday church services in the black village of Gungululu “unispiring” (15) is Magona’s foregrounding and prioritization of the indigenous religion of her people practised with abandon (12). A religious culture in which people believe in witchcraft related creatures like zombies and revere their ancestors as Magona’s fellow villagers do, do not see their indigenous consciousness and lifestyles in a hierarchical relationship with Christianity. By such a stylistic manipulation, Magona enriches her domestication of global feminism in a complex and questioning manner typical of the feminist project, especially in its advanced historical evolutionary stage of feminist postcoloniality. The cultural aesthetic of oral storytelling intensifies the indigenous cultural complex of which indigenous spirituality is a constituent. Apart from a strategic encapsulation of the written mode of narration within what the opening paragraphs of the autobiography inculcate as an originally verbal narration of the contents, Magona makes clear that the traditional folktales and riddles form the texture of how children in Gungululu were brought up (13). The observation that “In her autobiography, Sindiwe Magona draws on two sets of narrative conventions – those of Xhosa orature and those of western writing – and the resultant text is dialogic” (Daymond 2002:331) should accurately be seen as true not only of Mother to Mother (1998) which the writer specifically focuses on. Magona’s debut autobiography To My Children’s Children (1990) proves to be the fountainhead of a stylistic feature refracting Magona’s brand of feminism, later pervading her other works as I illustrate in the next sections of this chapter. One pertinent aspect of feminist postcoloniality is its orientation towards the kind of religious pluralism encoded in the discourse of To My Children’s Children. That is why Trexler (2007:46) states that “a feminist theology of religious pluralism” is committed to eradicating “hierarchy wherever it is found”, thus aiding “religious pluralism in undermining claims of Christian superiority.” It is important to note that as a member of oppressed blacks in the setting of the narrative, Magona creates an atmosphere of a myriad concurring religions, first as a way of defying an imposed hierarchical precedence of religions extraneous to the lifestyles of the indigenous blacks. Secondly, Magona acknowledges the existence of these other religions, believing that they are equal to the religion of her own community of fellow blacks and should be acknowledged as such. Yet in a manner identifying her with global feminists believing in intersectional group identity and the equality of the various blocks held together by varying identities, the narration of Magona’s autobiography does not posit homogenized intersectionality at the cost of the kind of cultural identity holding together the black South Africans. Historically, such a recognition of the simultaneous and nonhierarchical nature of oppressions” (Mann and Huffman 2005:60) is not unprecedented, yet 146 Magona’s addition of South African blackness and black womanness to the polyvocality of global feminisms is unparalleled in giving voice to what Mann and Huffman (2005:65) describe as “multiple realities that arise from diverse social locations.” Economic exploitation tied to her being a black woman is exposed when Magona moves from one domestic work to another, after losing a teaching job in which she and other black women are exploited in a manner worse that how black men are exploited and doomed to inhuman working conditions. While working for the Garlands as a domestic, she works “from seven in the morning to eight-thirty at night, Monday to Friday; and seven to two-thirty in the afternoon on Saturday; and Sunday, eight to ten-thirty” (124). Even migrant whites display racist solidarity with white apartheid rulers (137). As an expression of awareness of the hierarchical centering of white oligarchic exploitation of the subaltern globally, Magona bitterly protests that it is this migrant group of whites that she finds “hardest to swallow” (137). Magona’s weaving of her personal with national histories from the perspective of exploited black South African males and females during apartheid, characterizes her regard for the socio-political history of her people with the seriousness the African theorist Es’kia Mphahlele articulates as the “burden of our history we cannot afford to ignore” (Mphahlele 2002:83). From a black South African cultural point of view, Mphahlele (2004:27) sees the writer as someone consciously wanting “to give an account of himself as a product of historical process.” Magona should rightly be understood as a writer using autobiography to affirm the cultural perspectives of fellow black South Africans needing to have the agency to counteract white ruling class hegemony. This includes refined, nuanced cultural affinities such as those expressed by Mphahlele (2004:27) on the place of history and the writer within black South African culture threatened by apartheid oppression. It is for this reason that Loflin (1997:220) stresses Magona’s dissolution of self in her feminist discourse, with the remark that “Magona describes the oppressive conditions of black domestic workers under apartheid.” In a typically simultaneous feminist conforming and negating of global feminists concepts like womanism, Magona thus displays a complex delineation of the womanist Alice Walker (Mehta 2000:397) has described as a “communal mother … who is committed to the integrity, survival and wholeness of entire peoples due to her sense of self and her love for her culture.” Such a uniquely reconstructed womanism adds to the other concepts within a global feminist framework that Magona has appropriated in order to lend a ring of original peculiarity to the agency she represents in To My Children’s Children (1990) If Magona believes in feminist post-modernist and post-structuralist views of identity as “simply a construct of language, discourse, and cultural practices” (Mann and Huffman 2005:63), the cultural practices encoded into To My Children’s Children (1990) by means of her discourse using language as I demonstrate above are specifically black South African under apartheid conditions. In the same way the stylistic and discursive aspects of To My Children’s Children germinate seeds that continue to grow in Magona’s later work Mother to Mother (1998), her position also manifests itself in her short story collection Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night (1991), and in Forced to Grow (1992), her sequel to To My Children’s Children (1990). This is seen when Magona describes her domestic worker character Joyce in the short story collection as realizing that “a feminist perspective in South Africa is inhibited by racism” 147 (Magona 1991:59). This is testimony to Magona’s feminist project illustrated above to have started developing in To My Children’s Children (1990), when she declares her view that place for her “means less a geographical locality and more a group of people with whom I am connected and to whom I belong” (Magona 1990:1-2). Magona here concurrently associates with and dissociates herself from a layer of feminists characterized as transcontinental postcolonials known for downplaying the significance of identity attachment to a specific locale. It is such a Magonaesque feminist bent that has led to Boehmer (1999:169) observing that in Magona’s Mother to Mother (1998), “contrary to transcontinental post-colonials, home is experienced as being at once grounded, even if temporarily, and up in the air, in the sense of provisional” (Boehmer 1999:169). Before I move on to a discussion of Magona’s Mother to Mother (1998), it is worthwhile to show continued removal of racist discrimination in Magona’s urge for anti-patriarchal agency starting to show in To My Children’s Children (1990). Among the many autobiographical segments Magona chooses to put under a magnifying glass in Forced to Grow (1992) more than she does in To My Children’s Children (1990), is her transition from working under exploitative conditions as a teacher under the apartheid Bantu Education Department, to “nearly doubling [her] monthly earnings from forty-seven to seventy-two rand” working for yet another department of apartheid government called Bantu Administration (Magona 1992:82). Upon learning of Magona’s resignation from the school he heads, the male principal named Tabane reacts in a manner that paternalistically implies an objectification denying the fact that Magona herself has worked her way up the economic ladder, by remarking “now that I have scrubbed you, they all want you” (Magona 1991:82). Yet another black, a township ‘landlord’ named Ngambu, sympathizes with the patriarchal school principal by throwing Magona out of her rented room which, unlike the rest of the black township, “was large … had inside running water, hot as well as cold … had electricity” (Magona 1992:82). Magona (1992:82) purposely juxtaposes her plight with the fact that as a woman she “absolutely had no hope of being allowed to rent or buy a council house.” Inclusion of the restrictive impact of apartheid government’s macro-economic policies on the protagonist of Forced to Grow (1992) serves to clarify the comprehensiveness of Magona’s feminism in the way she handles autobiography. It is a recognized tenet of global feminism to foster “a clear understanding of how gender relations can affect progress toward [the formulation of] efficacious policies to promote societal development and raise living standards” (Berik et al. 2009:13). The township in which Magona rents a room in order to be close to her teaching job at Moshesh Higher Primary School does not have sufficient space and amenities for adequate human occupation (Magona 1992: 82). This situation is a product of conscious macroeconomic policy formulation by the white apartheid ruling class. While post-apartheid South Africa’s macro-economic policy may enjoy a limited role of national government due to restriction by post-national macro-economic dynamics characterizing today’s globalized economy, the apartheid government mostly afforded national monopoly of economic policy at the cost of international macro-economics. Besides, world economics between 1948 when the national party assumed rule in South Africa and 1994 when a new democratic South Africa dawned have not always been as post-structuralist or postmodernist and relatively 148 deracialized as today. In an interrogation of Magona’s feminist discourse displayed by her autobiographies, it is thus pertinent to pose the global feminist question Berik et al. (2009:13) concern themselves with, regarding “how gender and the macroeconomy interact.” The immortalization of Magona’s socio-economic holding down by both members of her black community and the macro-economics of the white apartheid state should be understood simultaneously as her shift to a deliberate painting of the whites running apartheid South Africa, symbolized the word “council” (Magona 1992:82), with the same patriarchal brush as the black school principal and ‘landlord’. Magona later explains that by council she is referring to the Cape Town City Council functioning under the Bantu Administration Department that is “charged specifically with the regulation of Africans,” where as an employee she “learn[s] a lot about [her] special hell as an African” (Magona 1992:83). Apart from achieving the kind of deracialized agentive display of both internal and external exploitation by lumping black and white patriarchy together evident in her earlier work To My Children’s Children (1990), Magona (1992:83) invokes her feminist religious pluralist orientation by means of the word “hell.” According to Trexler (2007:50, 52, 58) such a position is akin to a global feminist model for religious pluralism that is described as postpatriarchal, incorporating “a variety of resources and perspectives into theology” and leading to a stance that “all persons are created within the body of God and, as such, cannot be subjugated because of non-Christian beliefs.” In the same breath, Africanist theorists like Mphahlele have indicated that within African spirituality, western Christian notions of hell as some place one may be doomed to in the hereafter are replaced by notions of ‘paradisial’ well-being and possible lived hell in the here and now (Mphahlele 2002:154). In this way, by describing the life of black women under apartheid as hell Magona is simultaneously global and African, congruous to her pinning down of global feminism to be inflected in terms of her specifically South African notion of home. Such a feminist simultaneity renders Magona amenable even to global notions of what writers like Mann and Huffman (2005:81) conceive as a “decentering of the West” emanating from postmodernist feminism. The socio-political agency Magona urges through her discourse starting with her autobiography To My Children’s Children is achieved through a global womanism, poststructuralism or postmodernism and feminist postcoloniality that she inflects individually to account for her specific black South African home impinged upon by an apartheid national macro-economics. AGENCY URGED FOR BLACK SOUTH AFRICANS WITHIN THE APARTHEID NATION ON THE BRINK OF A COLLAPSE: MOTHER TO MOTHER AND MAGONA’S KIND OF INFLECTED FEMINISM Published four years into the new South Africa’s democracy inaugurated in 1994, Magona’s autobiography Mother to Mother (1998) aptly critiques an apartheid state turbulently shaken out of complacency by an intensifying struggle for the liberation of oppressed blacks, led by the blacks themselves. The narrative is set within the height of the liberation struggle when the ANC and other black liberation movements in exile and their supporters within the borders of a moribund apartheid state had joined hands through underground networks. Magona exemplifies such networks with the incidents leading up to 149 Mxolisi’s mother Mandisa meeting her son who is hiding away from apartheid police, through an intricate route arranged by freedom fighter comrades (Magona 1998:196-210). I will show that Magona continues gainfully to experiment with her feminism, sustaining the devices appearing in her earlier works. Magona opens the narrative in such a way that she creates an aura of orality, bridging the distance between herself and the murdered girl’s mother by means of a direct, I-narrator voice. Magona modulates the narrator Mandisa’s voice, transforming it from what would be a somewhat detached written kind of communication by means of an epistolary medium. The shocking salutation of the missive from the murderer son’s mother Mandisa to the mother of the slain white young American woman Amy Biehl is “My son killed your daughter” (1). Within the effective tautness of the monologue, a richly dialogic discourse unfolds, stretching the subject matter from the specific to the contextual, and from the self to the black and white nations of Mxolisi’s and Amy Biehl’s mothers. The many questions Mother to Mother (1998) opens with, chart the parameters of such a varied multidimensionality of focus, preparing the reader for the answers the narration implicitly undertakes to provide. Such a style reinforces Magona’s feminist perspective. Brisolara (2003:30) highlights the primacy of questioning within feminist theory, by pointing out that “Questioning leads to dialogue, which leads (though not necessarily) to organization or action toward changes.” At one time Magona’s questioning assumes the form of question, at the other a statement expressing a challenge to some (mis)perception. Phrases like “people look at me”, “where she does not belong”, “if she’s American”, “Where did she think she was going?” and “no white people in this place?”, all urge an agency that will change the status quo (Magona 1998:7, 8). What may simplistically be seen as a shirking of parental responsibility in the words “people look at me as if I’m the one” (7) and heartlessness in the accusation of the slain girl as a “white girl with nothing better to do than hang around in Guguletu, where she does not belong” (7), are technical shifts of focus from blaming the killer boy Mxolisi and his mother for the incident, to indicting apartheid rulers for creating and maintaining social conditions that render abnormality a normality. This comes out more literally in the narrator’s remark, “these monsters our children have become” (8). With such a shift effected, it is now understandable why the mother of the black boy is “not surprised” that her son has killed the addressee’s daughter. Boehmer is aware of the significance of Magona’s complex use of voice with one effect I show above, in her observation that “the narrator in Mother to Mother expresses deep bitterness at the nationalist rhetoric which has produced … the irrational violence that has engulfed her son” (Boehmer 1999:161). Of course, as I demonstrate, the bitterness is directed even beyond the national, commensurate with the complexity of Magona’s application of feminist ideas. Magona is quick to confine such a state in the upbringing of children to the black areas of “Guguletu, or … Langa, or Nyanga or Khayelitsha”, prefacing the phrase with a “Here” that associates the writer with the blacks and their locale, as opposed to opulent white areas of South Africa occupied only by whites in the heyday of the Group Areas and other discriminatory and oppressive apartheid legislation. It is such an aspect that Boehmer captures in her remark that for Magona “home is still an important concept, a core site of selfhood” (Boehmer 1999: 168). Magona reveals the geographically disjointed oneness of hers and her people’s home, with the suggestion that the white girl could actually have been killed by any other black South African child “in another far-away township in the vastness of 150 this country” (8). There is a telling tension in the expressions “if she’s American, all the better” (7), “where did she think she was going?” (8), “she probably saw that coming from the authorities, who might either hamper and hinder her” (9), “did she not go to school?” (8), “You don’t see big words … because one of us kills somebody, here in the townships” (9) and “the story was all over the place” (9). Among the many ‘silent’ statements Magona is giving a feminist voice to by these expressions, is that some fellow black South Africans have been so hardened by apartheid suffering that they cannot distinguish between what they dislike about the Reagan American administration of the time and the likeable mission of the white girl who has fallen victim to spiraling violence in black townships. At the same time, the white girl’s miscalculated visit to Guguletu is blamed on American blindness to the positioned nature of macro-economics and other fronts for global expansionism, where the girl personifies the American state with her failure to “go to school” properly on the reality of the apartheid South African situation. That the white girl banked on apartheid police to protect her from danger on the night she was is an acute assertion that at this point of South African black people’s appropriation of power, state machinery was powerless, with the power then in the hands of the ordinary black people in their numbers. Magona brings out her lampooning of the senseless economic policies of the apartheid state in her questioning why the government ironically “pays for [Mxolisi’s] food, his clothes, the roof over his head” (10) only now that he is imprisoned for ‘killing’ the naively innocent American visiting university student Amy Biehl. Here Magona’s global feminism is revealed, in her characterization echoing the postmodernist and post-structuralist feminist viewpoint shifting power for bringing about change to the masses, in her undermining of “structural views of oppression” and “treatment of power as more ephemeral and ubiquitous” (Brisolara 2003:64). Magona projects the powerless black masses as the now powerful in bringing about change. In the same vein, Magona externalizes her feminist sensibility of censuring an arrogant hegemony of the centre, this time represented by both apartheid South Africa and the United States of America of the time, in the way west controlled or manipulated media selectively report on the victims of violence along colour lines. It is one of the many feminist views that “What is spoken and who is silenced shapes the perception of reality” (Brisolara 2003:31). In recognition of this aspect of Magona’s feminism, McHaney (2008:176) remarks that Magona “seeks understanding by imagining the circumstances of the killers in lieu of hearing the story via the typical media attention given to the victim.” One more thread continuing in Mother to Mother (1998) is Magona’s encapsulation of local black South African lifestyles and consciousness within an atmosphere of indigenous spirituality and artistic form. Upon receiving news of Magona’s pregnancy out of wedlock, one of the worries uppermost in her mother’s mind is “What will the church people say?” (123). Implicitly Magona ties her overall discrimination on the basis of gender to her mother’s subjugated ingestion of the Christian ideas of sin. Magona satirizes the non-cultural notion of sin more explicitly at the start of the narrative, when she pleads for her murderer son in the words “Forgive him this terrible, terrible sin” (10). Calling the act a sin and not a mistake is in keeping with Magona’s subtle ascription of blame for his son’s beastly actions at least to apartheid conditions under which blacks live. Christianity, especially it Calvinist version, is one prominently known part of the fabric of apartheid South Africa. By invoking the foreign idea of sin, Magona implies that only white apartheid South Africa and the complicit 151 American state of the time are blind to the fact that what has happened is not a fault of her son’s. While what Daymond (2002:331) says concerning Magona’s fusion of a South African indigenous narrative style of orature with a conventionally western one is true, this should be stretched to include the fact that the indigenous takes precedence over the western. This justifies why Tatamkhulu even recasts the cattle killing Xhosa incident from portraying the black people of South Africa and their culture as less sensible and nuanced than the written history of the whites (185-195). As a retort to the child Magona’s distorted interpretation of the story of Nongqawuse, Tatamkhulu heightens the blame from individual teachers to the apartheid state employing them and the Bantu Education system, in the words, “These liars, your teachers … But, what can one expect? After all they are paid by the same boer government … the same people who stole our land” (188). When Tatamkhulu regales the young Magona with a genuine version of the cattle killing historical event, he ends up reciting “in the voice of an imbongi of the people” (188). Contrary to the blaming of gender related devaluing on what is often called cultural patriarchy of males within black communities in the west’s othering black South Africans, here we have a male elder displaying a profound valuing of the female by undertaking intimately to teach her the true story of her people. The raising of Tatamkhulu’s role to the traditional cultural one of a prophetic elder called imbongi imbues the character of Tatamkhulu with an epic dimension. In addition, this hoists the black indigenous story above that of the white oppressors. Magona achieves the same thematic effect with her characterization of Magona’s father not as a caricature always manipulated to live true to the western role of a traditional black South African male stereotyped by the west as paternalistic. While Magona’s mother does not relent in her ostricization of Magona for falling pregnant with Mxolisi, Magona delineates the character of Magona’s father as accommodative of what has happened (Magona 1998:138139). For this reason, the views of writers such as Loflin (1997: 213) that Magona’s suffering after she has fallen pregnant was motivated by the patriarchal state of black South African cultures not accepting that their daughters have matured into adulthood, seem to me to contradict Magona’s more nuanced discourse in this autobiography. CONCLUSION While Magona does apply global feminist ideas in the discourse of her autobiographies, she does so alongside distilling her own kind of feminism uniquely foregrounding black South Africans as a positioned focus of what would otherwise be an ineffectual, overgeneralizing global feminism. Not only is Magona “aware of the role of the apartheid State in the breakdown of communities, demanding interventions at community level” (Masemola 2010:116). She considers the community of black South African men and women first as the primary section of global society required to show agency and change the plight of her people, before she can resonate intersectionally with the other oppressed of the world. In this way Magona can be said to embrace the feminist economics insight recognizing that “Increased global economic integration … has caused income and wealth inequality to expand,” thus working against development by generating “intergroup inequality in gender, race/ethnicity, and class terms 152 (Berik et al. 2009:1). This position comfortably characterizes Magona as a world feminist, according to the global feminist aspect expressed by Trexler (2007: 47), of not only asserting “that women should be treated equally”, but broadening to maintain that “all people worldwide ought to be treated as equals.” It is thus noteworthy that Magona pushes forward the development of feminist theory on a world scale even as she provides an antidote to some hegemonic misperceptions concerning black South Africans as cultural groups. Some peoples belonging to the periphery will never be treated as equals within the feminist project for as long as their cultural identities are distortedly represented by feminists from the centre. One such distortion is what Magona rectifies in her discourse, that black South African cultures, though patriarchal like most western societies, are not inherently sexist because of this. Hence her characterization of male characters as culturally empowering and socially benevolent, while some woman characters come across as gender discrimination incarnate, meted out to same gender characters. Magona even apportions epic assertion of the black South African cultural voice within a global feminist framework to the male character Tatamkhulu (Mother to Mother 1998). It is Tatamkhulu who performs the agentive task of what (Loflin 1997: 220) sees as “preserving the knowledge of apartheid’s oppression for future generations.” This is why Tatamkhulu re-tells the cattle killing Xhosa historical event with a black voice, linking the historical freedom struggle to the liberation struggle within which Mother to Mother (1998) is set. One way Magona attains her unique enrichment of global feminism by bending it dialectically to account for the distinctive plight of black South Africans under apartheid, is by stressing stylistically that apartheid in South Africa has queerly conflated gender, class and race discrimination. This Magona achieves in an complex way of using the dynamics of local oppression of women and blacks to dovetail within global feminism’s stand that “sex and gender relations cannot be separated from race, class, sexual orientation or preference, and physical ability” (Brisolara 2003:27), and that feminism has “proven ability to understand diversity, complexity, and power, to give voice to what has long been silenced” (Brisolara 2003:33). Magona’s autobiographies deny a cultural silencing, including apartheid’s denial of what black South Africans among the oppressed of the world would gain from feminism’s inclination towards a postpatriarchal religious pluralism. It is through Magona’s refracted model of global feminist postcoloniality that the cosmology of black South Africans, including their own understanding of associating with the body of God through ancestral veneration, can be enlisted in the gains of feminist-driven social emancipation. While on a world scale children, the disabled and the poor may be the ones feminist approaches seek to rescue from discrimination and oppression, on the South African scene apartheid artificially constructed society such that poor and disabled coincided with black. This is why the protagonists of Magona’s autobiographies are painted as a confluence of economic, gender and apartheid oppression, as we see with the characters Sindiwe (To My Children’s Children 1990), Joyce (Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night 1991), Magona herself as narrator (Forced to Grow 1992) and Magona’s alter ego Mandisa (Mother to Mother 1998). Such a vantage point has led to MacHaney (2008:167, 180) correctly describing Magona simultaneously as offering “transnational intertextual readings” and a “polyphonic dialogism of [her] story of apartheid from the black South African point of view.” The launching pad of Magona’s dialogism and adding of a voice to global feminism on behalf of herself and her people, is her black South African home impinged upon by 153 apartheid restrictions. With such a voice, she engages in dialogue with apartheid rule, global feminism and global macro-economic politics (as with the United States of America or broad western hegemony in Mother to Mother 1998) – in true feminist polyphonic fashion. Among the many achievements towards urging agency against the apartheid status quo, “Magona describes the oppressive conditions of black domestic workers under apartheid” (Loflin 1997: 220). As my scrutiny of Magona’s biographies has demonstrated, what sweeps through all of them is a typically feminist attitude towards the past, the present and the future, especially in the way it is associated with what are historically known as third wave feminists (Mann and Huffman 2005:75). Right from To My Children’s Children (1990) through to Mother to Mother (1998), the overriding moral is, as Loflin (1997:220) comments about the discourse of the short stories in the collection Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night (1991), that “the systematic exploitation of black women’s labour … is coming to an end.” However, Magona’s feminist pessimism with the present and optimism with the future is much more profound than just urging agency for black South African woman emancipation. REFERENCES Berik, Günseli, van der Meulen Rodgers, Yana and Stephanie Seguino. 2009. Feminist Economics 15(3): 1-33. Boehmer, Elleke. 1999. Without the West: 1990s Southern African and Indian Woman Writers – A Conversation. African Studies 58(2): 157-170. Brisolara, Sharon. 2003. Invited Reaction: Feminist Inquiry, Frameworks, Feminisms and Other “F” Words. Human Resource Development Quarterly 14(1): 27-34. Daymond, Margaret J. 2002. Complementary Oral and Written Narrative Conventions: Sindiwe Magona’s autobiography and Short Story Sequence, “Women at Work.” Journal of Southern African Studies 28(2): 331-346. Loflin, Christine. 1990. ‘White women can learn not to call us girls.’ Journal of Modern Literature XX (1): 109-114. Loflin, Christine. 1997. Periodization in South African Literature. CLIO 26(2): 205-227. Magona, Sindiwe. 1990. To My Children’s Children (Cape Town: David Phillip). Magona, Sindiwe. 1991. Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night (Cape Town: David Phillip). Magona, Sindiwe. 1992. Forced to Grow (Cape Town: David Phillip). Magona, Sindiwe. 1998. Mother to Mother (Cape Town: David Phillip). Magona, Sindiwe. 2008. Beauty’s Gift (Cape Town: Kwela Books). Mann, Susan Arther and Huffman, Douglas J. 2005. The Decentering of Second Wave Feminism and the Rise of the Third Wave. Science and Society 69(1): 1-91. Masemola, Kgomotso. 2010. The Individuated Collective Utterance: Lack. Law and Desire in Autobiographies of Ellen Kuzwayo and Sindiwe Magona. Journal of Literary Studies 26 (1): 111-134. McHaney, Pearl Amelia. 2008. History and Intertextuality. A Transnational Reading of Eddora Wetty’s Losing Battles and Sindiwe Magona’s Mother to Mother. Southern African Literary Journal XL (2): 166-181. 154 Mehta, Brinda J. 2000. Postcolonial Feminism. Code, Lorraine (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Feminist Theories. (London: Routledge), 395-397. Mphahlele, Es’kia. 2002. The Burden of History and the University ‘s Role in the Recreating of its Community and its Environment. Ogude, J., Raditlhalo, S., Ramakuela, N., Ramogale, M., and Peter N. Thuynsma (Ed.) Es’kia (Cape Town: Kwela Books), 78-83. Mphahlele, Es’kia. 2002. The Fabric of African Culture and Religious Beliefs. Ogude, J., Raditlhalo, S., Ramakuela, N., Ramogale, M., and Peter N. Thuynsma (Ed.). Es’kia (Cape Town: Kwela Books), 142-156. Mphahlele, Es’kia. 2004. Afrikan Literature, Social Experience in Process Ogude, J., Raditlhalo, S., Ramakuela, N., Ramogale, M., and Peter N. Thuynsma (Ed.). Es’kia Continued (Johannesburg: Stainbank and Associates). Trexler, Melanie E. 2007. The World as the Body of God: A Feminist Approach to Religious Pluralism. Dialogue and Alliance 21(1): 45-68.