Proposal

advertisement

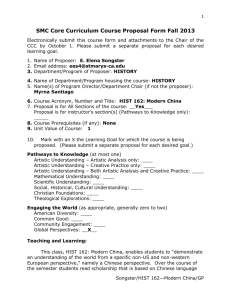

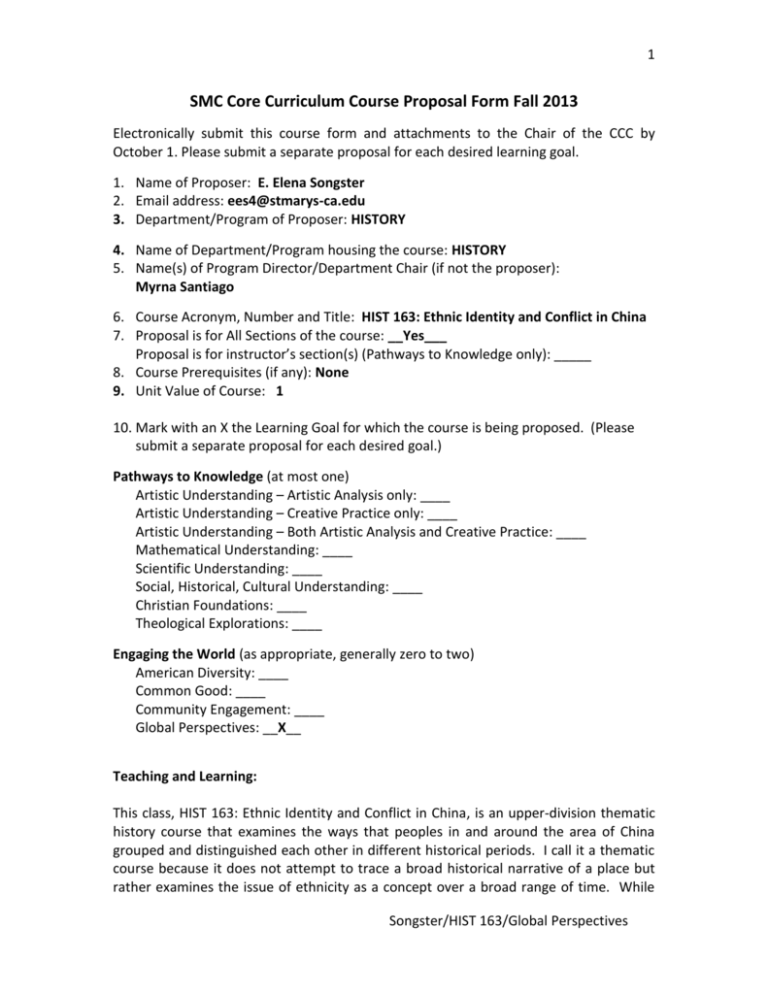

1 SMC Core Curriculum Course Proposal Form Fall 2013 Electronically submit this course form and attachments to the Chair of the CCC by October 1. Please submit a separate proposal for each desired learning goal. 1. Name of Proposer: E. Elena Songster 2. Email address: ees4@stmarys-ca.edu 3. Department/Program of Proposer: HISTORY 4. Name of Department/Program housing the course: HISTORY 5. Name(s) of Program Director/Department Chair (if not the proposer): Myrna Santiago 6. Course Acronym, Number and Title: HIST 163: Ethnic Identity and Conflict in China 7. Proposal is for All Sections of the course: __Yes___ Proposal is for instructor’s section(s) (Pathways to Knowledge only): _____ 8. Course Prerequisites (if any): None 9. Unit Value of Course: 1 10. Mark with an X the Learning Goal for which the course is being proposed. (Please submit a separate proposal for each desired goal.) Pathways to Knowledge (at most one) Artistic Understanding – Artistic Analysis only: ____ Artistic Understanding – Creative Practice only: ____ Artistic Understanding – Both Artistic Analysis and Creative Practice: ____ Mathematical Understanding: ____ Scientific Understanding: ____ Social, Historical, Cultural Understanding: ____ Christian Foundations: ____ Theological Explorations: ____ Engaging the World (as appropriate, generally zero to two) American Diversity: ____ Common Good: ____ Community Engagement: ____ Global Perspectives: __X__ Teaching and Learning: This class, HIST 163: Ethnic Identity and Conflict in China, is an upper-division thematic history course that examines the ways that peoples in and around the area of China grouped and distinguished each other in different historical periods. I call it a thematic course because it does not attempt to trace a broad historical narrative of a place but rather examines the issue of ethnicity as a concept over a broad range of time. While Songster/HIST 163/Global Perspectives 2 “ethnicity” is a modern concept, ancient peoples had systematic ways of dividing groups of people that in some cases were similar to modern notions of ethnicity and in other cases were very different from them. This course not only exposes students to an “understanding of the world from a specific non-US and non-Western European viewpoint,” (Global Perspective Learning Outcome) by being entirely focused on the history, writings, and peoples of the areas in and around China, but also seeks to expose students to the perspectives of the peoples who were and are on the periphery of Chinese society. These groups are in some ways another step removed from the western perspective as they are marginalized in the context of a non-western society. Furthermore, students are given an opportunity to examine these groups from the ancient period to the present. In so doing they are exposed to perspectives that pre-date interactions between these peoples and western peoples, giving them exposure not only to a non-western part of the world, but to a world completely devoid of any western influence whatsoever. By taking this class, students not only gain an appreciation for dramatic differences between the ways that Chinese and westerners categorize people and identify themselves, they also can see the shifts in the ways that peoples in these areas grouped and identified other peoples from the ancient to the modern eras. This course is explicitly designed to expose students to non-western ways of thinking and moreover to illustrate to students that within the context of “China” there are many layers and players and multiple perspectives on what it means to be both part of and apart from Chinese society. Students will demonstrate that they understand the various non-western perspectives that they are exposed to through weekly in-depth discussions of our readings, three papers, and two exams. Almost all of the readings examine non-western perspectives of the issue of identity. Discussion is important for helping students tease out these ideas. Just last week one student posed the question, “Did the practice of Chinese taking Khitans [another group that lived north of the Chinese empire at the time] as wives threaten their sense of ethnic superiority during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) by diluting their ethnic purity?” This question was answered well by another student who noted, “According to the reading Chinese perceptions of what constituted ‘Chinese’ were not based on bloodline at all, but rather on ‘how civilized’ or ‘uncivilized’ a particular group was according to Chinese criteria, so I don’t think that it would threaten their sense of cultural superiority because bloodline didn’t seem to matter at all really.” Each paper is designed to give students an opportunity to analyze the concept of human categorization in three distinct contexts. The first is more of a think piece for them to write about their understanding of this idea upon arrival to the course within the context of an example that is personal or familiar to them. This offers me a baseline of their understanding of this idea. The next paper requires that they analyze one of the groups we study and the way that that particular categorized itself with respect to the Han (Chinese) during the PRE-MODERN era. The last paper requires them to choose a different group and either focus on it in the context of the twentieth century (and beyond) or examine how this particular group’s identity changed from the pre-modern Songster/HIST 163/Global Perspectives 3 to the present-day period. In this way the students demonstrate their understanding not only of non-western perspectives on human categorization, but also how these perspectives vary from group to group and from era to era. Exams similarly require that students analyze specific aspects of these understandings by asking them to respond to such questions as: To what degree is religion an essential component of Tibetan and Hui (Muslim Chinese) identity after the founding of the People’s Republic of China (1949)? In what ways did the Xiongnu [a nomadic people on the northern steppe during the first and second centuries BCE] both exemplify and counter Chinese perceptions of a civilized society at the time? In what ways could you argue that the Chinese themselves contradicted their own notions of a civilized society? Notes: I am the only person who teaches this course. It therefore does not have any other sections, nor is there the possibility of it being taught in a different manner or with a different focus. The second and third papers are designed to demonstrate student understanding of non-western perspectives, as are the essay questions on either of the exams. Please see attached syllabus for further details on readings, topics, and assignments. Songster/HIST 163/Global Perspectives