NHM_Hurricane Grant Final Report Narrative Part A

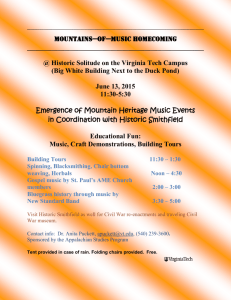

advertisement