Self-other differentiation (draft)

advertisement

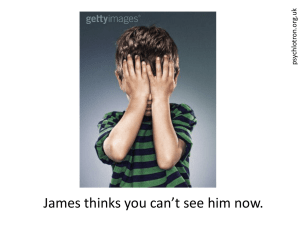

Self-other differentiation A new reading of theory of mind test In this paper I address the question of the genesis of children’s shift from self-other equivalence to recognizing the self and other as distinguished mental agents. I will agree with Barresi and Moore (2008) that this question concerns a developmental shift from mind-sharing to mind-understanding but will disagree with an adopted view that this shift can be granted to 18-month-olds. The child’s ability to recognize himself and the other as independent mental beings cannot, I will claim, be established previous to the age of cognitive maturation when the other can be seen as an independent epistemic/mental being, that is, before the positive accomplishment of the theory of mind test. In answering the question(s) of this paper the earliest stages of the child’s development will be discussed in the context of Piagetian empirical and theoretical framework as well as in relation to contemporary findings in cognitive psychology. Very early in their lives babies are capable of distinguishing between self-related and otherrelated stimuli. This is, as argued by many, only a perceptual ability that does not yet imply any understanding on the child’s part of a differentiation between oneself and the other. There are, however, two contradictory opinions on that matter. Some researchers would claim that the differentiation between self and other is in place already at the birth (e.g. Ruffman, 2004; Reddy, 2008; Stawarska, 2009) while others would distinguish between perceptual innate differentiation and the later-acquired understanding of this differentiation in ‘self’ and ‘other’ terms (e.g., Rochat & Striano, 2002; Hobson, 2004; Barresi & Moore, 2004). This understanding is reached, it is claimed, somewhere between 1 and 2 years of age. For, infants at this age, Hobson (1992, 162) argues, “… have come to recognize the psychological similarity, as well as the separateness, of self and others. They have come to perceive others as subjects of experience with their own psychological orientation toward the world and toward themselves …” Researchers usually defend this claim by referring to such achievements as children’s early accomplishments of mirror-recognition test, children’s ability at 2 years of age to take the other’s point of view and children’s at 2-3 years of age linguistic competences in using personal pronouns denoting themselves and the others in different social contexts (e.g. Butterworth, 1994; Barresi & Moore, 2008). The focal point of the disagreement between those who would claim self-other differentiation at birth and those who would defend the later differentiation story can, of course, be a disagreement about as to how self-other differentiation should be defined. Nevertheless, without making any attempt to settle the dispute it would be still legitimate to enquire: “In which sense should we understand that the young child with his ability to differentiate between himself and the other will until 4-6 years of age fail the theory of mind test and happily apply his own understanding of reality to the other?” The pivotal question which I would like to raise is to whether a child previous to his theoryof-mind accomplishment can be seen as apprehending himself as distinguishable from others when the others around the child have to have the view on reality that coincides with the 1 child’s. Another part of this question is also if the others apprehended by this child can be seen as having an independent (from the child) mental existence. Both parts of this question should be answered, to my mind, in the negative. I would claim that the question of self-other differentiation cannot be settled until a young child can pass the theory of mind test and thereby distinguish between his own and the other’s understanding of the world. Let us look now at the theory of mind procedure by paying a special attention to the relation between a subject and an object in the very act of acquiring knowledge about the object. The Epistemic Reading of Theory of Mind Test In their experiments with chimpanzees Premack and Woodruff (1978) were the first to coin the ‘theory of mind’ term. Inspired by their work Wimmer and Perner (1983) further elaborated the test algorithm in applying it to children. In Wimmer’s and Perner’s experimental procedure the child was asked about where the other is going to look for an object which, unbeknown to this other, had been relocated. The test procedure was arranged in the following way. The child and the other first observed how an object – a piece of chocolate – was placed in the location – x. When the other left the room a chocolate was replaced to another location – y. The child was then asked the theory-of-mind question of where the other would look for the chocolate upon his return. There were two alternatives for the child to answer this question – by pointing either at location x or y. The usual way of understanding this scenario (already suggested by Premack and Woodruff) is that the ability to understand the other’s mind or, in the case of human subjects, the ability to understand the other’s mental states, is tested. However, what is usually not discussed in this context is what the epistemic relation between the subject and the object of knowledge can tell us about the child’s apprehension of the other. In the case where the object is seen as being sought at the location x, the child shows a manifest understanding of another subject’s epistemic state. The other subject with his own understanding of reality, one that contradicts the actual states of affairs, is acknowledged. In the case where the object is seen as being sought at the location y the child failed the test. The child’s own reading of the situation is projected onto the other. In this case the other is not yet apprehended by the child as a subject with his own understanding of reality. The reason for this is that the child’s cognitive immaturity makes it impossible for him to account for a different outcome, depending on the other’s epistemic state. In other words, by failing the theory of mind test the child shows that the other is not yet recognized as an independent mental being but only as an other that is subjugated by the child’s social egocentrism. On this ground the process of self-other differentiation cannot be seen as accomplished before the age of passing the theory of mind test. Let us reflect on the consequences of this. The theory of mind experimental settings are usually understood as aimed to investigate the child’s capability to comprehend the other’s (and/or one’s own) mental states. But before asking for comprehension of other’s beliefs, desires or intentions one should check for the child’s comprehension of the other – a subject with his own (and not the child’s) view on reality. As long as the others’ understanding of reality coincides with the child’s – these 2 others will inhabit the child’s egocentric world and cannot be seen as distinguishable from the child as autonomous mental beings with their own beliefs, desires or intentions. That is, previous to the child’s acknowledgment of the other as an independent mental being the very question of the other’s beliefs, desires or intentions cannot be unequivocally formulated. To claim that self-other differentiation is not accomplished until 4-6 years of age – the age of passing the-theory-of-mind-test – is to make a claim in sharp contrast to the contemporary state of research: Toward the end of the first year, the child has acquired some basic understanding of persons as agents and as subjects of experience (Bretherton et al., 1981; Harding & Golinkoff, 1979). From this point, the child’s sense of commonality with as well as differentiation form other persons, together with his or her experience of being an “object” in the world of others, leads the child to realize his or her potential for taking an outside perspective on him- or herself and his or her own attitudes, and so to acquire selfreflective awareness in the second year of life. Hobson (1990, 173) This statement, expressed more than two decades ago, is still valid in relation to the current state of research with just a little correction that these conditions will reign to the end of the second year. Contrary to this I argue that until passing the theory of mind test there is no realization on the child’s part about, what Hobson claims, “an outside perspective on him- or herself” such that will allow him or her “to acquire reflective self-awareness.” To have an “experience of being an ‘object’ in the world of others” requires a vantage point from which the child can address himself as an object to be observed and/or investigated. To be able to take the other’s point of view on oneself the child is thus first in need of developing the conception of the other, such that the other’s point of view will not coincide with the child’s. This is precisely, as I argue, captured by the theory of mind procedure. What is in focus for the theory of mind testing is to determine whether the child has reached the stage of his development such that the other’s point of view on reality that contradicted the states of affairs (the “child’s own”1 point of view) could be accepted. Reaching this level of cognitive maturity will allow the child to use this newly discovered vantage point and for the first time be able to direct his attention toward himself. In other words, before passing the theory of mind test the child who has not yet discovered the other as distinguished from himself will also lack the ability to self-reflect.2 The reason that the expression “the child’s own” (or any other connotations of this expression in the text below) is placed in quotation marks is that it is not actually correct to use this expression in relation to the child who fails the theory of mind test. Previous to his accomplishment of the theory of mind task the child is still living in his egocentric environment without differentiating between different epistemic points of view, and thus, strictly speaking, cannot yet have his own as opposed to someone else’s point of view. The only possible point of view for this child is the state of affairs in reality, which often is also incorrectly addressed as “the child’s own” point of view. In other words, the consequence of the child's egocentric impasse is that the child cannot, strictly speaking, claim anything from his own point of view (more about this below). 1 2 The ability to self-reflect and be aware of oneself in a reflective way will be employed in this paper in Mead’s (1962) sense, that is, as an ability to take the other’s point of view on oneself as an object. 3 The proposal of self-other non-differentiation until 4 to 6 years of age and the child’s inability until this age to be reflectively self-aware is not at all uncontroversial. Besides the claim of a much later self-other differentiation the proposed reading of theory of mind test also reverses the usual explication of the theory of mind paradigm. The child’s ability to pass the test is often understood as dependent on his ability to self-reflect and thus compare his own understanding with the other’s. What is now claimed is just the opposite – the child’s ability to self-reflect (i.e., to take the other’s point of view on himself) is crucially dependent on the positive accomplishment of the test. We are confronted here with a dilemma. If we accept the proposed epistemic reading of theory of mind paradigm the question is then how we can understand the contemporary findings in cognitive psychology that seem to support the much earlier self-other differentiation view. How can the child, who does not until 4 to 6 years of age differentiate himself from the others, already at 2 years of age operate with different points of view and along with this also show an ability at 2-3 years of age of mastering personal pronouns? In defending the later self-other-differentiation view the main purpose of this paper will be thus to answer these questions. The aim is to show how contemporary findings in developmental and cognitive psychology can be reconciled with the proposed epistemic reading of theory of mind paradigm. The important question ahead is how this puzzle can be unraveled. The Way to Unravel the Puzzle I intend to start unraveling the self-other differentiation puzzle by looking more closely at the stage of young children’s development when they have not yet acquired the ability to refer to themselves in the above mentioned sense. To be able to do this we first are in need of a more accurate definition of the unequivocal term ‘self-reference’. The Notion of Self-Reference The notion of self-reference or reflective self-reference will be used in this paper as synonymous to self-awareness. By emphasizing the reflective nature of self-awareness I stand opposed to readings where self-awareness is seen as existing in two different modes – reflective and pre-reflective (the notion of so-called pre-reflective/non-reflective, preconceptual self-awareness is used by many to refer to individual’s “primitive” sense of self). By saying this I do not deny that a young child can have some innate sense of coherent self previous to his capacity for self-contemplation. However, I want to refrain from every enterprise of denoting this innate sense in terms of pre-reflective self-awareness. In my view the notion of pre-reflective self-awareness (as opposed to reflective self-awareness) is confusing. It is confusing not only because it (as non-intentional, non-reflective, nonepistemic and non-objectifying) resists an exploration in any positive terms and would require en explication of how one can non-reflectively manage in any way “to refer” to (or to be aware about) oneself and, at the same time, be able to apprehend that it is the self that this non-intentional and non-reflective reference or awareness is about; but also because it would 4 owe us an explanation of how the pre-reflective awareness of self as opposed to pre-reflective awareness of others’ selves is apprehended. By equating self-awareness with reflective self-reference I follow Mead’s (1962) distinction between consciousness and self-consciousness (self-awareness). It is only in the self-conscious state that an individual can have “an objective, non-affective attitude toward itself” experiencing himself “not directly or immediately, …, but only in so far as he first becomes an object to himself … and he becomes an object to himself only by taking the attitudes of other individuals toward himself within a social environment” (Mead, 1962, 138). In contrast to the self-conscious state a subject in his conscious state can, as Mead claims, be seen as immersed in very intense experience, an experience in which the self, in Mead’s words “does not enter (ibid., 137).”3 With this in mind can help us delineate the scope of application for the notion of selfawareness in these pages. It will not allow, for example, the following reading: “By the second year, the baby is entering the linguistic community and beginning also to show evidence of reflective self-awareness, or higher-order consciousness”4 (Butterworth, 1994, p.125). In the proposed reading of the theory of mind test, the child who has not reached the age of passing the test cannot recognize the other as an independent mental being and therefore cannot utilize this other in taking this other’s vantage point on reality and on himself. So in the proposed frame of reference the Butterworth’s two years old baby is not yet able to differentiate between two epistemic points of view – one’s own and that of the other’s – and as a consequence thereof cannot yet take another person’s point of view on himself, which would mark the child as capable of self-referential thinking. This baby will still be living in his egocentric environment, independent of his good accomplishment in the mirror selfrecognition test or his ability of alternating between different points of view (more about this see later). The outline of the investigation The proposed understanding of self-referential ability is defined in these pages as being opposite to Piaget’s notion of egocentrism – roughly a phenomenon of un-differentiation between the other and the self (Piaget, 1962, 243) and accordingly an inability of the young 3 Mead (1962) takes here a couple of examples: When one is running to get away from someone who is chasing him, he is entirely occupied in the action, and his experience may be swallowed up in the objects about him, so that he has, at the time being, no consciousness of self at all (ibid., 137). And another: There are also the pictures that flash into a person’s mind when he is drowning. In such instances there is a contrast between an experience that is absolutely wound up in outside activity in which the self as an object does note enter, and an activity of memory and imagination in which the self is the principal object (ibid., 137). Butterworth (1994) refers here to the child’s ability of mirror self-recognition, i.e., the ability of 18 month old infants or higher primates to point at a dab of rouge on the face by using the mirror reflection as a guide. 4 5 child to take the other’s point of view on himself. The dichotomy between self-reference and the inability to refer to oneself (egocentrism) makes it advisable to take a somewhat closer look at egocentrism. By looking at Piaget’s elaboration of the phenomenon we will account for some central features that characterize the non-reflective stage of the child’s development. In this context we will also reflect on current findings in developmental psychology that seem to support a much earlier self-other-differentiation view. These findings would include children’s accomplishments of mirror-recognition test, children’s early ability at 2 years of age to manipulate with different points of view as well as children’s linguistic ability at 2-3 years of age to master personal pronouns thus showing seeming competence in distinguishing themselves from others in different social contexts. In sum, to defend the claim of much later self-other differentiation the earliest stages of child’s development will be discussed in the context of the Piagetian empirical and theoretical framework as well as in relation to contemporary findings in cognitive psychology. Piaget and Contemporary Findings in Developmental Psychology Let’s begin by giving some overview of the Piagetian notion of egocentrism. The discussion will then proceed to further elaborations of Piaget’s insights in relation to contemporary findings in developmental and cognitive psychology. Egocentrism In several places in his papers Piaget noticed that the word egocentrism was not the best choice to denote the phenomenon he observed, for “… in daily speech, ego-centrism means referring everything back to oneself, i.e., to a conscious self, whereas, when we use the term ego-centrism, we mean the inability to differentiate between one’s own point of view and other people’s or between one’s own activity and changes in the object (Piaget, 1962, 267).” The egocentric state of a young child would imply, according to Piaget, at least two things: i) the confusion of subject with object, when, during the act of acquiring knowledge “the subject does not know himself and, in turning towards the object, is unable to uncentre himself” (ibid., 274) and ii) the confusion about one’s identity, that is, the state where the subject “cannot, as yet, completely dissociate this ego from another’s: between himself and another there is identification, even confusion rather than differentiation and reciprocity” (ibid., 274). This would further imply that the young child while living in his egocentric world would lack self-referential insight into his own egocentric predicament. Being entirely absorbed in the things he sees and seeing the “others only in a symbiosis” (ibid., 273) this child will be a “subject, who does not know himself, [and] cannot manage to get outside himself in order to see himself in a universe of relations” (ibid., 272). While being unable to connect happenings around him to any specifically identified subject, this child would also live in a total absence of rational system of reference or co-ordination between different points of view. The only point of view which would exist and which the child would not be conscious of would be his own. For this reason, egocentrism, as Piaget pointed it out is “a kind of systematic and unconscious illusion, an illusion of perspective” (ibid., 268). 6 In his elaboration of the phenomenon Piaget was referring to different species of egocentrism, e.g., social egocentrism, spatial egocentrism, verbal egocentrism and intellectual egocentrism. Importantly, as Piaget observed: “Social ego-centrism, as much as purely intellectual egocentrism, is an epistemic attitude: it is a way of understanding others just as ego-centrism in general is a way of looking at things” (ibid., 273). The focal point here is that the notion of egocentrism is aimed to describe something purely epistemic, something that underlies the child’s social behavior and not the other way around. For, as Piaget observed, egocentrism is “neither a conscious phenomenon (ego-centrism, when self-conscious, is no longer egocentrism), nor a phenomenon of social behavior (behavior is an indirect manifestation of egocentrism but does not constitute it)” (ibid., 268). It sounds paradoxical, but the gist of it all this is that any observations of a child’s social behavior would not be enough to bring us any insights about childish egocentrism. What Piaget seemed to indicate was that we could not study social behavior as supplying us with evidence for making any inferences about epistemic structures underlying child’s behavior. In Piagetian thought, intellectual egocentrism could still prevail even in the view of the child’s seeming conquest of his egocentric impasse in social behavior. In disregarding this intuition many developmental psychologists construe contrariwise their empirical investigation and draw their theoretical conclusions about the cognitive development of young children on the basis of their observations of children’s behavior. It is presumably by overlooking the puzzling implication of Piaget’s insight together with the inattentive applications of his notion of egocentrism that misled many cognitive psychologists to a quick rejection of Piaget's findings as outdated. We will turn now to two examples that will highlight this point. The first one applies to postPiagetian findings of children’s seeming ability, already in the second year of life, to take another person’s point of view; the second example concerns the child’s linguistic competence in mastering at three years of age reference to oneself (and others) by means of personal pronouns. Both these findings seem to contradict the Piagetian claim of egocentrism that should remain until 6–7 years of age. 7 References Barresi, J., & Moore, C. (2004). Even an “epistemic triangle” has tree sides. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 98–99. Barresi, J., & Moore, C. (2008). The neuroscience of social understanding. In J. Zlatev, T.P. Racine, C. Sinha, & E. Itkonen, (Eds.), The Shared Mind. Perspectives on intersubjectivity (pp. 39–66). Amsterdam: John Benjamin’s Publishing Co. Butterworth, G. (1994). Theory of mind and the Facts of embodiment. In C. Lewis, & P. Mitchell, (Eds.), Children’s early Understanding of Mind: Origins and Development (pp. 115–132). East Sussex: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd., Publishers. Hobson, R.P. (1990), “On the origins of self and the case of autism.” Development and Psychology, 2, 163-181. Hobson, R.P. (1992). Social perception in high-level autism. In E. Schopler & G.B. Mesibov, High-Functioning Individuals with Autism (pp. 157–177). New York: Plenum Press. Hobson, R.P. (2004). Understanding self and other. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 109– 110. Mead, G.H. (1962). Mind, Self, and Society. From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. C.W. Morris, (Ed.), Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1934) Piaget, J. (1962). The Language and Thought of the Child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul LTD. (Original work published 1926) Reddy, V. (2008). How Infants Know Minds, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. sense of self. Early Development and Parenting, 6 (3-4), 105–112. Rochat, P., & Striano, T. (2002). Who’s in the mirror? Self-other discrimination in Specular images by four- and nine-month-old infants. Child Development, 73 (1), 35–46. Ruffman, T. (2004). Children’s understanding of mind: Constructivist but theory-like. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2, 120–121. Stawarska, B. (2009). Between You and I. Dialogical Phenomenology. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio. 8