M-Learning: Creating Social Presence through Mobile Social Media

advertisement

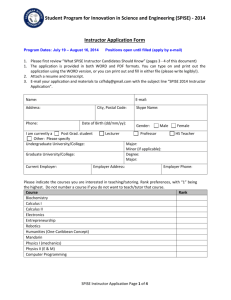

M-Learning: Creating Social Presence through Mobile Social Media Caroline Lego Muñoz Associate Professor of Marketing Fairleigh Dickinson University Natalie T. Wood Associate Professor of Marketing Saint Joseph’s University Edith Cowan University Contact Author: Caroline Lego Muñoz Silberman College of Business 285 Madison Ave. M-MS2-04 Madison, NJ 07940 FAX: (973) 443-8377 munoz@fdu.edu Voice: (973) 443-8093 1 “I never teach my pupils; I only attempt to provide the conditions in which they learn.” -Albert Einstein Students’ digital lives are becoming more complex with the rise of mobile technology and its social media applications. Smartphones and tablets are fast becoming the preferred method of communication over desktop computers. As a result, educators must adapt and begin to engage students in this new mobile frontier. M-Learning can provide new opportunities for sharing more immediate and interpersonal information which facilitates social presence. This paper explores the potential of social media mobile applications as an educational tool aimed at creating a social presence and encouraging learning beyond the confines of the traditional classroom. Specific social media mobile applications are provided to illustrate the different levels of social presence that they provide. Learning Styles of Today’s Students Learning can occur anywhere and at anytime. It does not need to be confined to the classroom or designated to a specific timeslot. Today’s traditional college students are largely part of Generation Y (born after 1982). Generation Y is accustomed to having instant access to information; pride themselves on their ability to multitask and value being connected to others 24/7 through their cell phones, instant messaging and other technologies (Brown 2000). Their willingness to use media and the desire to be connected with, and work with others opens up many exciting opportunities to create a social presence outside the regular class time. This may not only assist in the learning process but also encourage students to view learning as an enduring process rather than one that is confined to a specific day and time of the week. 2 Social Presence Learning is also very much a social practice (Laffey and Lin 2006; Shea, Fredericks, Pickett, Pelz, and Swan 2001). We learn with and through others. Learning outside the classroom can be encouraged by designing the class in such a way that it encourages a virtual social presence. Short, Williams and Christie (1976) defined social presence as “the degree of salience of the other person in the interaction of consequent salience of interpersonal relationships” (p.65). Scholars agree that social presence is affected by two factors: intimacy – the relationships we have with others, in this case fellow students and the instructor, and immediacy - that events happen without delay. The level of perceived social presence varies depending upon the type of communication mediums employed. Communication mediums exist on a continuum with face-to-face communication exhibiting the highest level of social presence and text based communication the lowest (Short, Williams and Christie 1976). The challenge for instructors is to select a communication medium and appropriate application that offers the proper level of social presence necessary for the level of interpersonal involvement that is required to complete the assigned task. Despite the historical focus on online learning, a place does exist for social presence in traditional face-to-face classroom based courses. In traditional settings instructors attempt to create social presence by employing a variety of tools such as course companion sites, blogs and wikis. As effective as these predominately web based tools are, some, but not all, allow for spontaneous communication and interaction with fellow students - largely because the student needs to be seated at a personal computer in order to utilize the tool. Given that students are spending more time on some mobile applications than course management systems (e.g. 3 Blackboard) (Dahlstrom, de Boor, Gruwalk, and Vockley 2011; Towner and Munoz 2012) and email use is decreasing (Bilton 2010; Kolowich 2011) it makes sense to explore alternative MLearning (Mobile Learning) opportunities. M-Learning: Smartphones and Tablets M-Learning (mobile learning) can be broadly defined as, “The point at which mobile computing and e-Learning intersect to produce an anytime, anywhere learning experience” (Kambourakis, Kontoni, and Sapounas 2004, p. 1). Since the mid-2000’s, technology that enables M-Learning has exploded, enabling a rise of situated learning (Alexander 2004). Through mobile devices, (such as smartphones and tablets), it is very easy for students to access information, communicate and share ideas, information and media “on the fly” offering greater opportunities over desktop and laptop computers for frequent interaction. The very nature of being mobile facilitates social presence by making communication both immediate and intimate. They afford students the opportunity to evaluate debate, share and strategize real world events together in synchronous time. Mobile social media applications may in fact be a more reliable, quicker way for instructors to interact with their students and for students to communicate and collaborate with each other on class related activities. Indeed, a number of mobile technologies have the potential to assist students in more easily creating work product - students are able to complete projects anywhere they physically are (provided they have a Wi-Fi connection) and immediately use information they find online. M-Learning, and the social media applications associated with it, also facilitates intimacy. For instance, mobile communication technologies such as Google + Group Video Chat can establish and forge working relationships among students. 4 Social Media Applications for Mobile Social Presence Students have already begun to organically adopt mobile applications for education (Dahlstrom, de Boor, Gruwalk, and Vockley 2011). Unfortunately, educators have been slower to embrace them. This may be attributed to a lack of knowledge related to how they work, their academic possibilities, and the logistics of how to use them effectively in the classroom. In evaluating mobile applications and their potential for creating social presence, an instructor must consider a number of factors. First, s/he should identify course content and associated activities that require interaction and communication outside the classroom. Next, an instructor should consider the types of communication (synchronous or asynchronous), communication modes, and the level of interactivity (i.e. collaboration potential) desired to successfully complete the activity. Before adopting or advocating for specific mobile applications an instructor needs to understand the number of students who have adopted smartphones/tablet technology in their courses and what operating systems they are using. From here, the instructor needs to evaluate potential applications to ensure that they offer the required features both in their mobile and desktop versions – for the benefit of those students who do not own a mobile device and will need to use a personal computer. Instructors should also test potential smartphone and tablet accessibility issues with online posted course materials. Finally, instructors needs to decide just how much direction they should provide students and clearly communicate their expectations for a task including level and type of participation. Table 1 provides a summary of some the more popular forms of mobile social media, methods of communication and additional features that they offer. Each of these applications listed provides an instructor and their students with increased opportunities for immediacy and intimacy beyond 5 the conventional course management systems, wikis and blogs that have become staples of many classes. In addition, the unique mobile nature of these applications encourages and facilitates students’ abilities to capture, discuss and share still images, video, and online information immediately when they come across them in their real and virtual world. While we attempt to segment social media applications primarily by communication mode, it should be noted that it is limiting to view social presence solely on the types of technology (e.g. text, video, etc.). There is a continuum of social presence, with some technologies affording more social presence than others, and evolving cultural practices (such as emoticons) can some overcome some technological limitations. Conclusion In general, M-Learning is something that all instructors must consider. Mobile technology use is high – and will only increase. It has the potential to dramatically enhance social presence in its ability to create immediacy and efficiently convey intimacy. Social presence is not only for online classes, but traditional, face to face classes can also benefit from outside classroom learning using mobile applications. Creating a social presence requires the careful selection of the right application/s for the tasks. Without question, M-Learning can facilitate conditions where pupils learn for themselves. 6 TABLE 1. Level of Social Presence in Social Media Mobile Applications Mobile Application Facebook Synchronous X LinkedIn Google+ WordPress X Asynchronous Extensive Text Info/ User/Profile Information Comments X X X X X X X X X X X X Videos with Audio X X X Still Images Interactive Document Creation/ Collaboration Messaging (Chat/Instant Message) X X X X X X X X Twitter X X YouTube X X X SocialCam X X X VoiceThread X X X X Pinterest X X X X Email based Messaging X X X X X X X References Alexander, B. (2004). Going Nomanic: Mobile Learning in Higher Education. Educause Review. 29-35. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERM0451.pdf. Bilton, Nick. (2010, August 17). For the class of 2014, No e-mail or wristwatches. New York Times. Retrieved from http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/08/17/the-class-of-2014-no-e-mail-orwristwatches/ Brown, J.S. (2000). Growing up digital: How the web changes work, education and the ways people learn. Change, 32(2), 10-20. Dahlstrom, E., de Boor, T., Grunwald, P., & Vockley, M. (2011), The ECAR National Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2011 (Research Report). Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, October 2011. Retrieved from 7 http://www.educause.edu/ecar. Kambourakis, G., Kontoni, D. P. N., & Sapounas, I. (2004). Introducing attribute certificates to secure distributed e-learning or m-learning services. Proceedings of the IASTED International Conference. Innsbruck, Australia, (436-440). Retrieved from http://ben.upc.es/butlleti/innsbruck/416-174.pdf Kolowich, S. (2011, January 6). How will students communicate? Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2011/01/06/college_technology_officers_consider_changin g_norms_in_student_communications. Laffey, L., & Lin, G. Y. (2006). Assessing social ability in online learning environments. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 17(2), 163–177. Shea, P. J., Fredericks, E., Pickett, A., Pelz, W., & Swan, K. (2001). Measures of learning effectiveness in the SUNY learning network. In J. Bourne, & J. C. Moore (Eds.), Online education: Learning effectiveness, faculty satisfaction, and cost effectiveness, 2(31–54). Needham, MA: SCOLE. Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunication. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Towner, T. & Muñoz, C. (2012). Facebook vs. web courseware: A Comparison. In C. Cheal, J. Coughlin, & S. Moore (Eds.), Transformation in Teaching: Social Media Strategies in Higher Education, (343-372). Santa Rosa, C.A.: Informing Science Institute. 8