ctamj2011 - Minnesota State University, Mankato

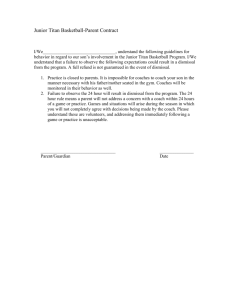

advertisement