Higher English Close Reading Skills Builder

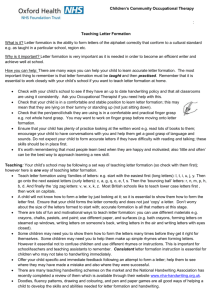

advertisement