Please make sure you are ready for the CAPT essay tomorrow. The

advertisement

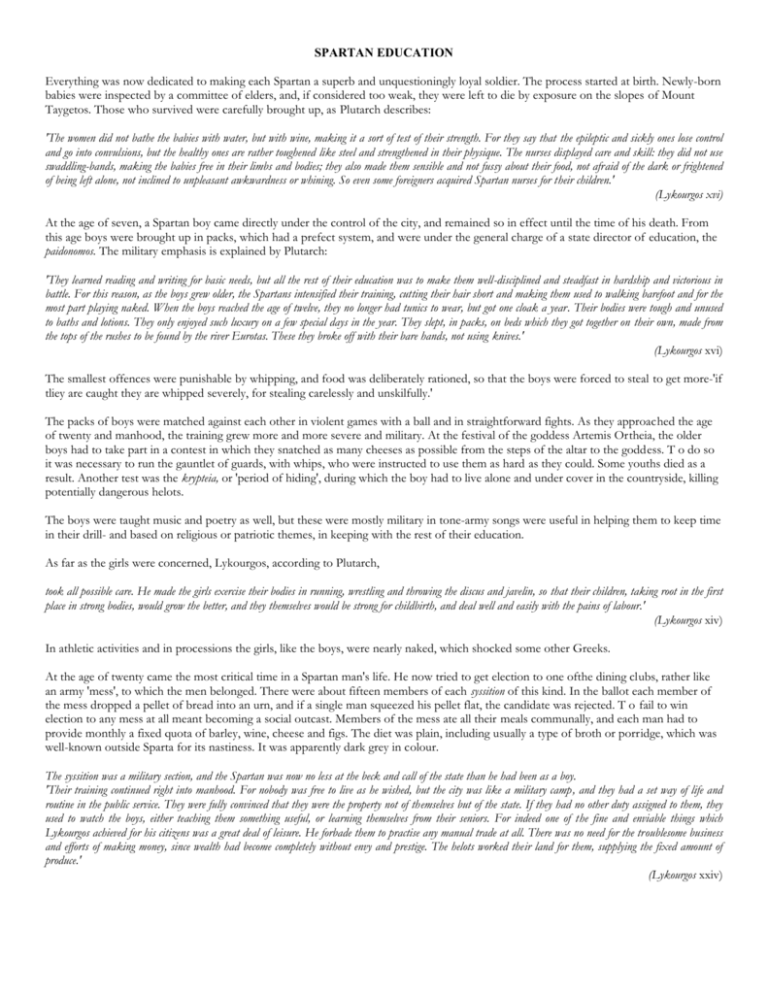

SPARTAN EDUCATION Everything was now dedicated to making each Spartan a superb and unquestioningly loyal soldier. The process started at birth. Newly-born babies were inspected by a committee of elders, and, if considered too weak, they were left to die by exposure on the slopes of Mount Taygetos. Those who survived were carefully brought up, as Plutarch describes: 'The women did not bathe the babies with water, but with wine, making it a sort of test of their strength. For they say that the epileptic and sickly ones lose control and go into convulsions, but the healthy ones are rather toughened like steel and strengthened in their physique. The nurses displayed care and skill: they did not use swaddling-bands, making the babies free in their limbs and bodies; they also made them sensible and not fussy about their food, not afraid of the dark or frightened of being left alone, not inclined to unpleasant awkwardness or whining. So even some foreigners acquired Spartan nurses for their children.' (Lykourgos xvi) At the age of seven, a Spartan boy came directly under the control of the city, and remained so in effect until the time of his death. From this age boys were brought up in packs, which had a prefect system, and were under the general charge of a state director of education, the paidonomos. The military emphasis is explained by Plutarch: 'They learned reading and writing for basic needs, but all the rest of their education was to make them well-disciplined and steadfast in hardship and victorious in battle. For this reason, as the boys grew older, the Spartans intensified their training, cutting their hair short and making them used to walking barefoot and for the most part playing naked. When the boys reached the age of twelve, they no longer had tunics to wear, but got one cloak a year. Their bodies were tough and unused to baths and lotions. They only enjoyed such luxury on a few special days in the year. They slept, in packs, on beds which they got together on their own, made from the tops of the rushes to be found by the river Eurotas. These they broke off with their bare hands, not using knives.' (Lykourgos xvi) The smallest offences were punishable by whipping, and food was deliberately rationed, so that the boys were forced to steal to get more-'if tliey are caught they are whipped severely, for stealing carelessly and unskilfully.' The packs of boys were matched against each other in violent games with a ball and in straightforward fights. As they approached the age of twenty and manhood, the training grew more and more severe and military. At the festival of the goddess Artemis Ortheia, the older boys had to take part in a contest in which they snatched as many cheeses as possible from the steps of the altar to the goddess. T o do so it was necessary to run the gauntlet of guards, with whips, who were instructed to use them as hard as they could. Some youths died as a result. Another test was the krypteia, or 'period of hiding', during which the boy had to live alone and under cover in the countryside, killing potentially dangerous helots. The boys were taught music and poetry as well, but these were mostly military in tone-army songs were useful in helping them to keep time in their drill- and based on religious or patriotic themes, in keeping with the rest of their education. As far as the girls were concerned, Lykourgos, according to Plutarch, took all possible care. He made the girls exercise their bodies in running, wrestling and throwing the discus and javelin, so that their children, taking root in the first place in strong bodies, would grow the better, and they themselves would be strong for childbirth, and deal well and easily with the pains of labour.' (Lykourgos xiv) In athletic activities and in processions the girls, like the boys, were nearly naked, which shocked some other Greeks. At the age of twenty came the most critical time in a Spartan man's life. He now tried to get election to one ofthe dining clubs, rather like an army 'mess', to which the men belonged. There were about fifteen members of each syssition of this kind. In the ballot each member of the mess dropped a pellet of bread into an urn, and if a single man squeezed his pellet flat, the candidate was rejected. T o fail to win election to any mess at all meant becoming a social outcast. Members of the mess ate all their meals communally, and each man had to provide monthly a fixed quota of barley, wine, cheese and figs. The diet was plain, including usually a type of broth or porridge, which was well-known outside Sparta for its nastiness. It was apparently dark grey in colour. The syssition was a military section, and the Spartan was now no less at the beck and call of the state than he had been as a boy. 'Their training continued right into manhood. For nobody was free to live as he wished, but the city was like a military camp, and they had a set way of life and routine in the public service. They were fully convinced that they were the property not of themselves but of the state. If they had no other duty assigned to them, they used to watch the boys, either teaching them something useful, or learning themselves from their seniors. For indeed one of the fine and enviable things which Lykourgos achieved for his citizens was a great deal of leisure. He forbade them to practise any manual trade at all. There was no need for the troublesome business and efforts of making money, since wealth had become completely without envy and prestige. The helots worked their land for them, supplying the fixed amount of produce.' (Lykourgos xxiv) ATHENIAN EDUCATION One Greek system of education has already been described in our earlier chapter on Sparta. The typical education provided for young Athenians was very different. The Athenians, although just as concerned that their sons should know how to behave correctly and to be good citizens, allowed the individual to develop much more freely than the Spartans. In contrast to Sparta, with its state official in charge of education, Athens left the organization in private hands. Although there was probably no law compelling parents to educate their sons at school, it was certainly the strong tradition to do so. The state paid for the schooling of some children, whose fathers had died fighting for the city. There were some laws relating to education: parents had to make sure that journeys to and from school took place in daylight; unauthorized persons were banned from school property in school hours, so that pupils might be protected from bad influences. Otherwise the state did not much interfere. Little will be said here about the education of girls, for, as far as we can tell, their upbringing took place almost entirely in their own homes. Some managed to learn to read and write, but they did not receive the same formal education as the boys. Their training was the responsibility of their mothers, by whom they were taught the skills necessary for running a home-weaving, spinning and so on-as well as correct behavior. Whatever they learnt beyond that was picked up by their own efforts. There were certainly those who managed to become cultured and well-informed. An Athenian boy first attended school at the age of about seven, and the primary stage of education lasted until he was about fourteen. He began by learning to read and to write, and to do simple arithmetic. His teacher in such subjects was called a grammatistes-gramma is the Greek word for a letter, with its obvious English derivations. In many cases the school itself was simply a single room, perhaps hired, or even the corner of a courtyard in the open air. So the number of pupils in anyone school would generally be small. Furniture was little more than stools or benches, and there were no desks (see fig 15.1). The boy was constantly attended by a paidagogos, a slave whose duties were to supervise him at home and at school, where he generally sat in on the actual lessons, besides escorting him to and from school, and carrying his satchel. He was responsible for teaching the boy good manners and could cane him if he thought fit. In fact he was an ever-present representative of the boy's father, his owner. Of course the suitability of such slaves for their job varied widely, and many were not at all suitable. They were generally despised. Pericles, on seeing a slave fall from a tree and break his leg, is reported to have said 'There you are. He's only fit to be a paidagogos now.' It is odd, when education was considered in theory so important by the Athenians, that they chose such people to supervise it. In a similar way the status, and often the ability, of the school masters was very low. Anybody could set himself up as a teacher, without any qualifications. Their pay was poor, and they dared not offend the parents on whom they depended for their fees. An idea of their reputation is given by the orator Demosthenes, in a speech made in the fourth century B.C., when he taunted his political opponent, Aischines: 'Your childhood was spent in an atmosphere of great poverty. You had to help your father in his job as assistant teacher-preparing the ink, washing down the benches, sweeping out the class-room, and taking the rank of a slave rather than of a freeborn boy.. .' (On the Crown 258) And later, by way of an insult: 'You were a teacher. I went to school.' Corporal punishment was accepted as normal. We are told that even before the boy reached school age he was, if disobedient, 'straightened up with threats and beatings, like a warped and twisted plank.' It must often have appeared the only way for a desperate schoolmaster, given little respect by anybody. The fact that pupils were allowed to bring their pets into class cannot have helped, nor the presence on occasion of bystanders with nothing better to do. There were no school holidays of the modern type, but the schools were closed on the days on which the city celebrated its various festivals. The month roughly equivalent to our February was particularly full of such days and so became the nearest thing to a prolonged break from school. The teaching of the grammatistes must have been extremely dull. He certainly made no deliberate effort to make it interesting. Learning by heart and continual reciting were stock methods. Reading was made more difficult by the fact that there was no punctuation, nor were there any spaces between written words. All reading was aloud, as the Greeks did not practice silent reading. For writing they used wooden tablets with wax surfaces, on which they would write with the sharp end of a stylus and rub out with the blunt end. There were also sheets made up of strips of papyrus reed, which could be written on in ink with a reed pen. As soon as the boys were able to read well enough, they were made to study and learn by heart extracts of poetry, especially from the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer. Some even learnt these entire poems by heart. All kinds of moral lessons were drawn from the poetry studied. Greek poetry was intended to be sung to the accompaniment of the lyre, and it was partly because of this that the Athenian boy also received instruction at his school from the kitharistes, or music-teacher. He was taught to play the kith'ara, that is the lyre, and the aulos, which was rather like an oboe, and to sing. The Greeks regarded it as essential for a cultured man to be able to sing and to play an instrument, especially the lyre. Apart from its connection with poetry, musical education was considered very important because of the Greek belief that music-of the right sort-had a beneficial effect in the molding of character. All the education provided by thegrammatistes and the kitharistes went under the general name of mousike. The Greeks used the term in a much wider sense than our word 'music', to include all the classroom side of schooling. The name is derived from that of the Muses (Mousai), the goddesses of the arts. During his elementary education in other subjects, the Athenian boy also attended the palaistra, or wrestling-schooL This was a courtyard with changing and washing facilities at the side. The palaistra was an educational establishment owned privately by the chief instructor, the paidotribes, recognizable by his purple cloak. Here the boys were given athletic training, mainly for the sports which made up the Greek pentathlon (see Chapter 8). They were also given instruction in general bodily care. The physical side of education was emphasized because the Athenians thought that physical appearance and fitness were as important as, and a great help to, high moral and intellectual standards. A frequent description of the ideal man occurring in Greek literature is that he is kalos k'agathos, literally 'handsome and good'. Yet the training received at the palaistra was also useful as preparation for military service, for which every citizen was liable, if required, between the ages of eighteen and sixty. A good summary of the traditional elementary education given at Athens, and of the theories behind it, is to be found in the writings of the Athenian philosopher, piato: 'Parents send their boys to school and instruct the schoolteachers to pay much more attention to the good behavior of their boys than to their letters and their music. The teachers take note accordingly, and as soon as the boys learn their letters and have reached the stage of understanding what they see written down as well as they have previously understood what they hear spoken, then they give them the works of the good poets to read at their benches and make them learn them by heart. In these works there are many moral lessons, and there is much description and praise of the good men of history, so that the boys may strive to imitate them and endeavor to become men such as they. Then in a similar way the music-teachers take care over the correct behavior of the boys and see that they do nothing wrong. Also, when they learn to play the >, kithara, they are taught the works of other good poets, the composers of the songs which are set to the music of the kithara. The music-teachers make sure that the boys' souls become familiar with rhythms and harmonies, so that they become more civilized, and, by becoming more rhythmic and harmonious in themselves, become effective in word and deed. For all human life requires rhythm and harmony. Finally, besides all this, parents send their boys to the paidotribes, so that by improvement their bodies may be the servants of their minds, which are now in a healthy state, and so that the boys are not compelled to be cowardly in wars and their other duties, because of the weakness of their bodies. The parents who do these things are the ones best able to do so, and those who are best able are the wealthiest. The sons of these people are the ones who begin to go to school at the earliest age and finish their schooling the latest.' (Protagoras 325 Dff.) The children of poorer parents had to find some form of employment once their elementary education had been completed. The wealthier, however, continued their education in a less formal secondary stage. They were now expected to attend the assembly, the market-place, the law courts and the theatre. Here, in the company of their fathers and others older than themselves, they learnt at first-hand about adult life in the city. They often now continued their physical education at the gymnasion (see p. 149), and those with a particular talent in any sport were given further training in it by specialists.