How to be a HOOD-lum: Medieval hoods

advertisement

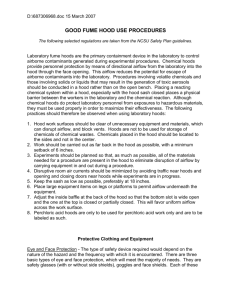

How to be a HOOD-lum: Medieval hoods A Workshop & Notes by Cynthia Virtue aka Cynthia du Pré Argent Hoods are a particularly useful item of clothing. They add another layer over the top of the body-head, neck and shoulders--which is exceedingly effective in keeping us warm outside, or keeping off the sun. It seems that most medieval cloaks/capes did not have an attached hood, instead they were worn with a separate hood like these. The mere act of covering your head, even if it's with only one layer of cotton, will make you a lot warmer on chilly nights, or while you sleep, and it protects you from that annoying hair-part sunburn during the day. In addition to these practical matters, hoods are fun! You can wear them many ways, you can trim them, you can use them as pockets, you can tie your friends' liripipes together, and they are easy and quick to make. Suggested fabrics: anything. Well, anything you'd wear to an SCA event. In general, use woven natural fabrics, such as cotton, linen or wool. If you find a lovely fabric that is scratchy, line it with a softer one. You can trim them with dags, bells, "nailheads", beads, etc., and you can "parti" them, too. If you're not sure what sort of hood you want, or don't trust your design skills, copy one of the ones in this handout, or from a medieval illustration. See the Men's Hats page for more medieval illustrations of hoods. The "evolution" of the hood. Hoods, started out as basic, efficient clothing for everyone. They were worn both "normally," as well as on top of the head as hats. Then they started mutating, depending on the social class of the wearer, and as time went on. Although I've used the word "evolution" it seems that the simpler versions continued in use, even while the more stylish hoods where being used by the upper classes, or by middle class folks on special occasions. Basic hoods: not much different than a folded piece of cloth with a seam in the back to make a poncho-like hood. Then they start being fitted at the neck, to reduce bulk, make a better line, and keep them on the head better. Then they finally get way out of hand -- peasant women with liripipes that go to the ankles (not very useful for a working woman), ornate dags on the liripipe and hood skirts, folding them so that the skirts become very ornamental cockscombs when worn as a hat, or wearing them on top of the head with the skirts hanging down behind. Illustration sources: 1. Man from "Peasants Dancing" end of 15th century, French 2. Man with hood on head from the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, 15th c. English 3. Drawing by the author 4. Woman from "Peasants Dancing" end of 15th century, French 5. Man with long dagged liripipe from the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries 6. Man with apparently fur hat and hood on shoulders from Histoire du Grand Alexandre, Fr 15th c 7. Man with long pointy liripipe, illustration from an Arthur story, 1450, French 8. Lorenzo de Medici Patterns for Hoods There are lots of ways to achieve the hood shape. Here are two: Mistress Tangwystyl's, from her period patterns class, and the adapted version that I tend to use, which is less tailored. From Mistress Tangwystyl's Class: Heather Rose Jones was the first person to put out the word in my area that patterns and extant items of this sort were in museums. This news excited me tremendously, and got me started anew with medieval clothing. This was around 1994. She notes that this pattern was interpreted from two 14th century English hoods. (Crowford et al pp 190-2) and has been scaled up from the original. She reports that her main innovation was the pattern layout to make best use of the fabric. Cynthia's versions: You can make this with a wide neck, sewn shut, so that you won't have to make buttons & buttonholes, (see first digram) or with a narrow neck and have some sort of closures which can be left open, or closed, for a closer fit (second diagram.) How to measure for your head: Take measurements of your victim -- one around the widest part of the head (parallel to the ground, like a crown) and also measure the height of the neck from chin to collarbone. Use one half of the head measurement, plus two inches, to be the dimensions for an imaginary square drawn on folded fabric (see the diagram, measure A.) From this central square, extend the square in one direction for the "cuff" of the face opening (however far you like; 3 inches is a good start; longer if you want to wear it rolled up a lot.) If you're making a single-layer hood, life is easier if this cuff edge is on the selvedge -- you won't have to hem it. From the lower corner of the square on the cuff side, draw straight down as long as you want the 'skirts' to go. Do the same for the back edge. You may wish to angle this out slightly for more shoulder room. You will be putting a gore at this seam as well. From that back-edge lower point of the square, draw a smooth curve upwards to extend into the liripipe. The other place that gores go is on either side of your neck in the front -- which on this pattern is about 4-5" from the front seam. Cut a slit from the hem upwards. Finally, cut the gores. My skirts tend to be about 8" long (plus the neck dimension) and maybe 4" wide at the end, but the gores need to be as long as the skirts. Be sure to round them off like pie-pieces. They don't need to be very wide -- use scraps. The larger picture at left is a quick version without gores. It does tend to be less graceful across the front of your chest than if you'd put gores in like the smaller diagram shows. However, there's no reason you couldn't cut it like this and put in gores from the scraps. Note that the large schematic shows two different "cape" sizes. Follow the cutting lines for whichever one you want. The long cape will go down to mid-upper-arm. The measurements are for an Adult Large size; adjust as needed. Assembly: Sew one gore each in the front two slits. Additional gore(s) on the back seam is optional. Add on the liripipe if you have a pieced, long liripipe. Sew front neck seam and then seam the back together; finish the edge of the skirt and the face opening. Some suggestions on construction: If you wash your fabric once or twice before you cut out your pattern, you can wash the garment later without fear of much shrinkage. You can even do this to silks and woolens. Washing will also make them softer next to your skin. You can dag the skirt in two ways. If you use fulled (shrunken) wool fabric, you can just snip ornamental dags out with scissors. Or you can line the hood and sew dags, then turn them inside out for a great look. Don't get over-enthusiastic about lining the hood and turning it inside out. If you do more than just one side (skirt or hood) this way, you'll end up with a lesson in topology -- you'll have a donut of fabric, not a hood. The looser version takes about two yards of narrow material. Double this, of course, if you are using a lining. Reduce this estimate if you are making a fitted hood. If you are parti-ing your hood (one color on one side, another on the other) you need one yard of each color. Contrasting linings can do double duty as outsides, too -- two hoods for the packing space of one. Long liripipes can be pieced out of scraps. Hood fittedness generally follows the style for other outerwear. If your garb is fitted, so should your hood fit snugly. If your garb is loose and flowy, so too, your should should be. Very fitted hoods will need buttons at the neck. Hoods (and hats in general) in period usually did not match the color of the rest of the outfit. They are an ideal use for bits of fabric that do not "coordinate" with the rest of your wardrobe, or pieces that are too small for other uses. Liripipes should not be long enough to drag on the ground when the hood is hung around the neck, because you'll trip over them or get them exceedingly dirty. It is period to tuck the liripipe into your belt, or wrap it round your neck or the skirts of the hood, so that it doesn't drag as much. Check out medieval illustrations for more ideas and authentic details. The wider the "skirt," the better the hood will look. If it turns out too snug, you won't be able to move your arms well -- put in more gores. I haven't done much research on the later women's bonnet-hood; the sort that was usually red or black, and open in the front to fit over the headdress. If you have any insights, on this or other hat subjects, please share them with me! Article © 1999 and 2005 Cynthia Virtue http://www.virtue.to/articles/hoodlum.html There are lots of how-to and YouTube pages on constructing Medieval garb. The following on how to make a hood came from this linked list of articles: http://www.virtue.to/articles/ Here are other links found on this site: Basic Garb (1000-1300)- Men and women's costumes, hats, accessories; an overview and instructions for newcomers (class) Tunic Worksheet (1000-1300) -- More specifics on the period cutting plan of the glorious T-Tunic -properly cut, it's one of the most elegant garb choices. (class) How to wear a veil, or a veil and circlet (or just a circlet) gracefully (1000-1300 or so) Plus The Dreaded Muffin-Head Effect