Constructive total loss defined.

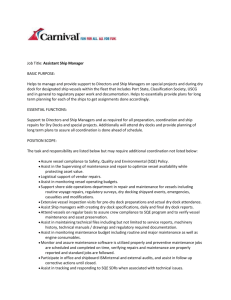

advertisement