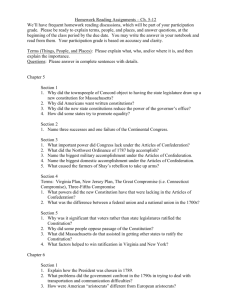

Units IV, V The American Revolution was not a radical

advertisement

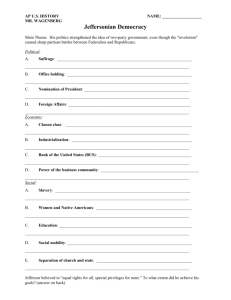

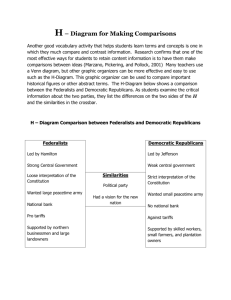

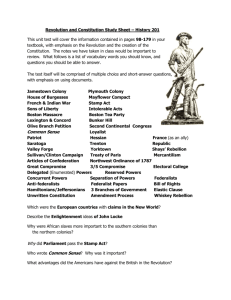

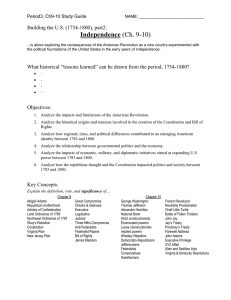

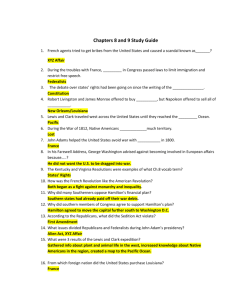

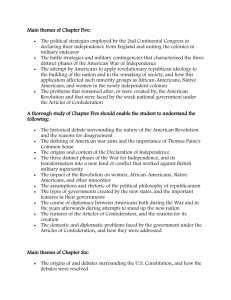

Units IV, V The American Revolution was not a radical transformation like the French or Russian revolutions, but it did produce political innovations and some social change in the direction of greater equality and democracy. Despite the inadequacies of the Articles of Confederation, the government did address a significant problem associated with disputed land claims by passing the Northwest Ordinance. The government was unable, however, to prevent British and Spanish encroachments and influences in the west. Compromise on a number of issues, was required in order to create the new federal Constitution. Adopting the new document required great political skill and involved changing the ratification process defined in the Articles of Confederation, writing persuasively in support of the stronger central government, and promising to add amendments to protect individual liberty and states’ rights. The federal Constitution represented a moderately conservative reaction against the democratic and decentralizing effects of the Revolution and the Articles of Confederation. In effect, it embedded the revolutionary ideals of liberty and popular government within a strong framework designed to advance national identity and interests against the dangers of fragmentation and disorder. Because of opposition from antifederalists, the Constitution extended certain delegated powers to the federal government, while reserving important powers to the states. Further, a Bill of Rights was later added. Led by Washington and Hamilton, the first administration under the Constitution overcame various difficulties and firmly established the political and economic foundations of the new federal government. The first Congress under the Constitution, led by James Madison, also contributed to the new republic by adding the Bill of Rights. The cabinet debate over Hamilton’s financial measure expanded into a wider political conflict between Hamiltonian Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans – the first political parties in America. Federalists supported a strong central government, a loose interpretation of the Constitution, and commerce (business). (Democratic) Republicans supported states’ rights, a strict interpretation of the Constitution, and agriculture (farmers). Some historians, however, contend that the two adversaries represented two types of wealth and class: manufacturers and planter-slaveholders. The French Revolution created a severe ideological and political division over foreign policy between Federalists and Republicans. The foreign-policy crisis coincided with domestic political divisions that culminated in the bitter election of 1800, but in the end, power passed peacefully from Federalists to Republicans. American isolationist tradition emerges as a result of Washington’s strong neutrality stance and his farewell warnings about foreign alliances. Many historians consider the election of 1800 a revolution in political ideas, aspirations, and objectives. Others point to TJ’s political moderation as president. Jefferson’s effective, pragmatic policies strengthened the principles of a two-party republican government, even though the Jeffersonian revolution caused sharp partisan battles between Federalists and Republicans over particular issues. The Marshall Supreme Court handed down decisions that would not only establish the foundation of the judiciary’s responsibilities, such as the power to determine the constitutionality of laws, but also reaffirm the separation of powers among the three branches of government. Despite his intentions, Jefferson became deeply entangled in the foreign-policy conflicts of the Napoleonic era, leading to a highly unpopular, failed embargo that revived the moribund Federalist Party. James Madison fell into an international trap, set by Napoleon, which Jefferson had avoided. Western War Hawks’ enthusiasm for a war with Britain was matched by New Englanders’ hostility.