The Translation Studies Reader

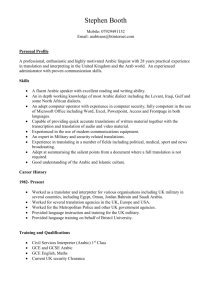

advertisement

1 TRANSLATION-SPECIFIC LANGUAGE 'UNIVERSALS': The Case of Arabic Translated Texts* 1. Introduction The objective of the present paper is to test the validity of two hypotheses concerning the specificity of translational language, viz. the occurrence of linguistic 'universals' postulated to be typical of all translations. The two translation generalities whose occurrence in Arabic translated texts is investigated are: 'repetition avoidance' and 'explicitation'. The first is seen in the marked tendency in translations towards the deletion of lexical repetitions found in the ST; whereas the second in the presence in translations of a higher degree of explicitness as represented, for example, by adding explanatory notes, filling in ellipsis, or using explicit sentence connectors. The two hypotheses are tested by analyzing and contrasting a number of English-Arabic and Arabic-English translated texts so as to be able to ascertain the frequent occurrence of these two translation phenomena which are postulated to be translation 'universals'. The role of the translator as a mediator of messages between two sets of linguistic and socio-cultural situations leads to the result that the translator also assumes the role of a ________________________________________________________ 2 *This paper was first read, in a shorter version, at Atlas Fifth International Conference on Current Issues in Translation, held in Amman, Jordan, during 18-19 December, 2005. text mitigator. This means that s/he comes to introduce, consciously or subconsciously, some linguistic modifications into the target text so as to be able to communicate efficiently with a readership living in a different place and, usually, at a different time as well. This process of mediation and mitigation may help explain the tendency in translational language towards explication, simplification, and reduction of unnecessary repetitions so as to alleviate the processing effort for the new reader. It has also resulted in the phenomenon observed by many translation researchers that: translations are more similar to one another than to originals in the target language [and] that not all linguistic features specific to translations are reducible to interference – other sources are required to explain the rest of the distance between translations and non-translations on the one hand, and the proximity of translations to one another. (Mauranen & Kujamäk 2004:5) Persistent observations, like the above, have led to the conclusion that the language of translated texts does not exactly represent language as used in free communicative events. Rather, it is similar to the type of language which is produced under constraint, like that used by foreign-language learners for instance. As a result of such pressures, the language of translation would tend, for example to "flaunt certain conventions and overuse certain features known to be characteristics of style in the target language" (Hatim: 3 2001:153). Or, it would exhibit certain patterns of texture, e.g. repetitions in the source text tend to be either deleted or reworded (Schlesinger1991 & Toury1991). In the same vein, Blum-Kulka remarks that the process of text interpretation conducted by the translator on the source text results in a target text which is more redundant than both the source text as well as comparable target texts. As an example of this increased redundancy, she points out that the cohesive patterns in translated texts are neither according to those of the TL norms nor those of SL norms, but follow a system of their own (1986:33). Many other scholars have made similar observations about the language of translated texts and have consequently started to search for the 'regularities', or 'laws', or 'tendencies' common to translated texts in general. This search is worthwhile in that it can shed more light on translation, both as a process and as a product. Based on such recurrent observations and research findings, researchers have begun to focus even more on studying the language of translated texts and some of them have suggested different names to depict this specificity of this language. Frawley (1984), for example, proposes the term 'third code' or 'third text' to emphasize the fact that translational language results from the confrontation of the source and target codes/texts and that it is distinct from both. Others, following Selinker in the context of communicating in a non-native language, suggest to call it 'interlanguage' or 'mediated language' so as to attract attention to the fact that it is a sort of constrained communication, unlike that of free language use (Chesterman 2004:45). Still others, like Schäffner & Adab (2001) prefer to use the term 'hybrid text' in order to stress that translated texts exhibit features which are somehow 'out of place'/'unusual' for the target culture. They add, however, that these texts are still accepted in the target language since they fulfill their intended communicative functions and that the features which they show "are not the result of a lack of translational competence 4 or examples of 'translationese', but are evidence of conscious and deliberate decisions by the translator". Nomenclature notwithstanding, the important thing to remember is that although translated texts exist only in the target language in which they are written and although they represent one of its subsystems as a result, the language of such texts is unique in many respects. In order to shed more light on the details of this uniqueness, a brief survey of research whose aim is to unveil the common linguistic regularities typical of translated texts is given below. 2. The Specificity of Translational Language The quest for regularities in different phenomena is characteristic of all branches of human knowledge which aspire to acquire the status of being scientific disciplines. All sciences seek generalities and try to go beyond the particular. The main movement of most scientific research has thus mainly been bottom-up, beginning with particular cases and then moving up to general laws. In Descriptive Translation Studies, this means the search for and the identification of linguistic regularities by relating translated texts to: (a) their source texts, (b) the original texts of the languages they are composed in, and (c) other translated texts both within the same language or across languages. In her seminal paper on "Corpus Linguistics and Translation Studies", Mona Baker reports that a number of scholars in the field have been lately engaged in research representing all the three types just mentioned above. They have managed, as a result, to arrive at some conclusions concerning translation regularities. These include the following, among others (Baker 1993:243-5): 5 (i) A higher level of explicitness, compared both to source texts as well as to original texts in general. Both Blum-Kulka (1986) and Toury (1991) have stressed that 'explicitation' is a feature commonly found in the translational language of both professional and non-professional translators. One example of this explication policy is when translators add explicit information which has been only implicitly understood from the source text. (ii) A marked tendency towards disambiguation and simplification. This is found, for example, when 'potentially ambiguous' personal pronouns in the source text are replaced by common or proper nouns with precise reference so as to resolve ambiguity (see, Vanderauwera 1985:97-8 and AbdelHafiz 2004, among others). Moreover, a marked tendency has also been detected to make difficult syntax in the ST language easier in the TT. (iii) A preference for conventional 'grammaticality'. In this respect, Shlesinger (1991:150) reports a strong tendency in oral translations, i.e. interpretations, to "round off unfinished sentences, grammaticize ungrammatical utterances and omit such things as false starts and self-corrections (as quoted in Baker 1993:244). (iv) A tendency for avoiding repetition found in the source text. This is realized, for example, by deleting instances of frequent lexical repetition or rewording them (Shlesinger 1991 & Toury 1991). (v) A general tendency to overuse linguistic features characteristic of the target language. For instance, the frequent use of binominals, which is common in both Arabic and Hebrew writings, has been found to occur more frequently in 6 translated Hebrew (Toury1980:130). than in its non-translated texts Similarly, Chesterman draws a list of regularities noted by researchers to occur in the language of translated texts. Chesterman, however, prefers to call them 'potential universals' rather than just 'regularities'. Moreover, he classifies them into two broad categories, viz. (a) Potential Suniversals (S referring to the Source Text), and (b) Potential T-universals (T standing for the Target Text). Chesterman's list of 'potential universals' in translational language includes the following (2004:40): (a) Potential S-universals: - Lengthening: i.e. translated texts are usually longer than their source texts - The law of interference: (Toury 1995) - The explication hypothesis (Blum-Kulka 1986) - Reduction of repetition (Baker 1993) (b) Potential T-universals: - Simplification: as noted in less lexical variety, lower lexical density, and more use of high-frequency items (Laviosa 1998) - Untypical, and less stable, lexical patterning (Mauranen 2000) 7 The search for translation regularities has specially witnessed an upsurge of activity since the mid-nineties. Large-scale electronic corpora have then become available as research tools and many scholars have consequently become capable of arriving at more reliable results. Such corpora have, for example, enabled researchers in Translation Studies to confirm, refute or modify many of the above-mentioned hypotheses on translational linguistic regularities which hitherto had been only made on the basis of small-scale corpora and manual analysis. Many research projects based on computerized data banks of multi-million words have soon begun to develop, especially in the U.K. and elsewhere on the Continent. Almost all of these compare English with one or more other languages, usually from within the Indo-European family. As for Arab scholars and Arabists, there are yet no large-scale computerized parallel or comparable research projects or corpora known to be available for either translated or original Arabic texts. As a result, there are no large-scale analyses and comparisons of Arabic translated texts either with their source texts in other languages or with other original texts within Arabic itself. Nor are there available yet studies which compare the language of translations in Arabic with that of translated texts in other languages. However, there have been many individual attempts to study translational Arabic in order to detect some of its linguistic characteristics. Limited as these may be both in scope and corpus, they can still provide the ground for much-needed extensive research in Arabic texts in general, and translated texts in particular. Both Mona Baker (1992) and Basil Hatim (1997) have, for instance, discussed several examples of Arabic translated texts in their books and pointed to some of the features of language specificity, such as a characteristic high level of explicitness 8 compared to their English source texts. Others, like Aziz (1997), Abdulla (2002) and Abdel-Hafiz (2004), among others, have written research papers describing some linguistic aspects of translational Arabic such as lexical repetition, usually as compared to English. Al-Khafaji, as well, investigates "the various linguistic alternatives open to the English-Arabic translator [when] confronted with the task of having to convert a large number of passive verbs in his English source text into other linguistic forms if he were to produce a normal Arabic text, free of gross translation interference" (1996:19). A parallel pair of texts consisting of an original English scientific text and its Arabic translation has been investigated for this purpose. Two other papers of alKhafaji compare the use of punctuation marks in an Arabic translation with its English source text, as well as with original Arabic texts (1999 and 2001). Taken together, the two papers thus represent an example of a combined parallelcomparable contrastive text analysis. The fourth paper within Arabic Descriptive Translation Studies by al-Khafaji was an attempt "to 'detect' [translational norms] and 'describe' the various types of shifts, in the area of lexical repetition, which have occurred in an Arabic-English translation" (2006). The study also tries "to 'explain' the underlying factors that may have prompted the various decision-making processes behind these translation shifts" (ibid). Finally, I have analyzed a number of parallel English-Arabic and Arabic-English translations in the present paper for the purpose of testing the occurrence of some of the common linguistic tendencies exhibited by translational Arabic, as well as by translational English. The following is a brief description of the data, the research method, and the results of this analysis. 3. Data and Results of Analysis 9 3.1. Data and Methodology In order to test the validity of the two above-mentioned hypotheses concerning the specificity of translational language in general, I have investigated a number of Arabic and English translated texts. The data consists of four texts: two Arabic-English translations and two English-Arabic ones; the latter two are translations of the same English source text, but by two different translators. All the texts belong to the literary genre of the short story.1 The reason I have chosen to analyze both Arabic and English translations, and not just Arabic, is two-fold: (a) to double-check the results of analysis by including translations from two different languages as well as by examining two translated texts from each language rather than one, and (b) to avoid the possibility of attributing the results of analysis to stylistic preferences in Arabic and/or English, rather than to tendencies common in all translations irrespective of their source languages. Moreover, the translations of four different translators, two in each direction, have been used as data lest the results be misinterpreted as being translator-specific. The analysis of the four translated texts has been confined to the search for two of the abovementioned translation 'universals' only: Repetition Avoidance and Explicitation. The main objective of the data analysis, a sample thereof is given below, is to ascertain the occurrence in the Arabic translated texts of the above two translation tendencies which are widely postulated in the literature. The method of analysis basically consists of carefully analyzing and contrasting the translated texts with their source texts in order to look for manifestations of these translation The two Arabic original short stories are الحافلة تسيرand الخروج من دائرة الصمت. They have been translated into English by Nancy Roberts and Abdulla Shunnaq, respectively, with the titles: Bus Walk and Out of the Silence. The English short story, on the other hand, is A Rose for Emily by Faulkner. It has been translated by A. al-Aqqaad and A. Abdulla as وردة الميليand وردة الى اميلى, respectively. (See the list of References at the end for the full facts of publications of the above.) 1 10 'universals'. The purpose, on the one hand, is thus to detect any instances of lexical repetition in the ST which are, completely or partially, deleted in the TTs or are replaced by synonymous words or are paraphrased. On the other hand, and for the detection of explicitation, the text contrastive analysis would search for instances where the TTs exhibit explicit background information which is only implicit in the STs, or show the replacement of any potentially ambiguous pronominals or other deictic words in the STs by their explicit referents in the TTs, as this sort of disambiguation is also considered here as part of the explicitation strategy.. 3.2. Results of Analysis Reported below is a summary of the results of data analysis. These are basically divided into two groups: one for reporting the realizations of each of the two tested translation 'universals', viz. repetition avoidance and explicitation. It has been deemed sufficient to report ten examples in each group as representative of each of the two 'universals': five from the Arabic translated texts and five from the English ones. Each of the twenty examples, selected from the two groups and reported below, comprises a source-text portion followed by its translated version. Thus, forty text fragments in all are cited below. For the purposes of the present paper, which is only a brief report on a pilot study, and not a full-fledged statistical one, this limited number of examples seems indicative. There are, however, many more similar examples which have been detected throughout the data analysis. 3.2.1 Repetition Avoidance in Translation 11 (A) Examples from the English-Arabic Translated Texts2 1.a - They were admitted by the old Negro into a dim hall from which a stairway mounted into still more shadow. It smelled of dust and disuse – a close, dark smell. The Negro led them into the parlor. It was furnished in heavy, leather-covered furniture. When the Negro opened the blinds of one window, . .. أدخلهم الزنجي الهرم الى ردهة مظلمة تفضي الى سلم يؤدي الى مكان- 1.b وكانت تتصاعد هنالك رائحةة الباةار والنفةنم ومةن ةم قةادهم الةى. . أشد ظلمة فلما فتح شراعة احدى. وهي مفروشة بأ اث قيل مبطى بالجلد.قاعة األستقاال . . . النوافذم ( al-Aqqad( 3 (Notice that the translator has retained only the first occurrence of 'the Negro' and deleted the other two, replacing them by the two implicit third-person pronouns in قةادand فةتح. The translator has avoided the three frequent and proximate instances of lexical repetition of the source text although Arabic is known to be highly tolerant of lexical repetition in its original texts. Instances like the above are indicative of the specificity of the language of Arabic translated texts. This language seems to exhibit certain special features which are somewhat different from those of the source language and the target language. However, it is still possible to argue that the deletion of repetition in Arabic is due to the fact that the verbs قةادand فةتحwould, on their own, each refers to a masculine third-person singular subject while their English counterparts 2 In the examples cited, I have underlined some words in order to highlight the linguistic elements which are directly relevant to, or affected by, the shifts due to the translation tendency under discussion. 3 After each of the illustrative text portions, cited as examples from the two Arabic translations and the two English ones, the name of the translator is given in parentheses immediately following the example. 12 do not. Reference to ' الزنجةةيthe 'Negro' can thus still be retrieved and sustained, without any ambiguity, in the Arabic translation, but not in the English source text. But when we find out that the same phenomenon of repetition deletion is also detected in English texts translated from Arabic, as in those which will soon be cited below, lexical repetition can no longer then be attributable to Arabic-specific stylistic or linguistic characteristics as such. 2.a - "Just as if a man – any man – could keep a kitchen properly," the ladies said; so they were not surprised when the smell developed. كانت السيدات في دهشة حينما انتشرت هذه الرائحة الكريهة مةن بيتهةام- 2.b al-( . . . .قلةن ان أي رجةل يسةتطي أن يقةوم بتنظيةل المطةا وكثيةرا مةا )Aqqaad (The second occurrence of man in the ST is deleted in the translation.) 3.a – That was when people had begun to feel really sorry for her. People in our town, remembering how old lady Wyatt, her great aunt, had gone completely crazy . . . ويةذكر أهةل بلةدتنا كيةل جنةت. هذا والناس يأسون لحالها في الحقيقةة- 3.b .خالتها السيدة ويات (al-Aqqaad) 13 (In the above, the translator has avoided the close repetition of 'people' by rewording in Arabic the second occurrence of the word in the ST, viz. using أهةل بلةدتناinstead of النةاسHence, the translation shifts of either 'deletion' or 'rewording', are alternatively used to avoid lexical repetition as can be seen from the above examples.) 4.a – The little boys would follow in groups to hear him cuss the niggers, and the niggers singing in time to the rise and fall of picks. وكان صةبار الصةايان يتوافةدون فرافةات ليةروه وهةو يسةو الزنةوج- 4.b ) a l-Aqqaad ( .وينهرهمم وهم يبنون م حركة المناول صاعدة وهابطة (Here, the translator has replaced the second occurrence of 'the niggers' by the pronoun هةةةم, despite the potential ambiguity which may result from this in the translated text: Does the pronoun refer to صبار الصايانor to ? الزنوجMoreover, the translator has opted to remove lexical repetition although repetition is usually rhetorically motivated in literary texts, like in the ones cited here.) 5.a – Colonel Sartoris invented an involved tale to the effect that Miss Emily's father had loaned money to the town, which the town, as a matter of business, preferred this way of repaying. – كان الكولونيل سرتوريس قد ابتدع قصة ليفهم الناس أن والد السيدة اميلةي5.b ) al-Aqqaad( .ساق فأقرض المدينة قرضا وأنها تختار هذه الطريقة لسداده 14 (Does the pronoun in وأنهةاrefer to السةيدة اميلةيor to ? المدينةةThe above Arabic sentence is ambiguous due to the substitution of the second occurrence of 'the town' of the ST by a pronoun in the TT. Once again, and despite the potential ambiguity, the translator has chosen to remove the lexical repetition. This is yet another clue of how entrenched the repetition-avoidance tendency is in translated texts; including Arabic ones, as can be seen from evidence displayed above.) (B) Examples from the Arabic-English Translations – في المرة األولى كنت أقود سيارتيم في المرة الثانية بند أساوعين علةى6.a األولىم كنت أقود حافلة فارهة عريضةم وكأطول ما تكون عليه هذه الحةافتت .الحديثة 6.b – The first time, I was driving my car. The second, which was two weeks after the first, I was behind the wheel of an enormous swift bus – the longest type that exists. (Roberts) (There are three different instances of lexical repetition in the Arabic text extract above: المةرة, كنةت أقةود, حافلةة. None of the three repetitions is retained in the English translated text: the second occurrence of المةرةhas been deleted, that of كنةت أقةود reworded, and of حافلةalso deleted.) الالةةدةم ورث المشةةيخةم والاندقيةةة والبض ة مةةن. عاةةدالرحمنم شةةي. – الشةةي7.a .آبائه وأجداده 15 7.b – Sheikh Abdel-Rahman had inherited his position, his rifle and even his hostile disposition from his ancestors. (Shunnaq) (In order to avoid the lexical repetition of the word . الشةيor its derived form المشةيخة, the translator has deleted the second occurrence of the ST's lexical chain in the translated text, while the third has been replaced by the general word 'position'.) ورث المشةةيخة والاندقيةةة والبض ة م فقةةد اعتةةاد أن يطةةو. وألنةةه الشةةي- 8.a بسيارته اللوري على الفتحين في مواسم الايادرم يجم شواالت القمةح للفقةرا سر قيامه بهذه المهمةم قةائت ّ . في الاد فسر الشي.واأليتام في القرى المجاورة هنةةاا الكثيةةر مةةن األيتةةام والفقةةرا فةةي القةةرى المجةةاورةم والبةةد مةةن أن يم ة و .بطونهم بالخاز 8.b – The Sheikh's raids on the villages at harvest time began as soon as he was given his title and position. Each time he made a raid, he would demand sacks of wheat, ostensibly for the poor and orphans in neighbouring villages. He used to say that there were many poor people who needed to have their stomachs filled with bread. (Shunnaq) (In the Arabic ST extract above, there are two lexical chains: one headed by . الشةيwhile the other by الفقةرا واأليتةام فةي القةرى المجةةاورة. In the English translation, however, the second instance of the first chain, viz. المشةيخةis replaced by the title and position whereas the third by the pronoun he. As for the second instance of the second lexical chain in the ST, it has 16 been largely deleted, except for the word poor which has been retained.) – كنت كنادتي ال أستطي رد طل بوسني تلايتةه ألحةدم وخمنةت ولةم أكةن9.a مخطئا أن ماادئ القيادة واحدة سوا لسيارة أو لحافلةم وبةودي حقةا أن أخةوض .التجربة لمجرد خوضها 9.b – As usual, I couldn't turn down a request if it was in my power to grant it. I surmised correctly that the rules of driving are basically the same for both cars and buses. Besides I really did want the experience, simply for the sake of having it. (Roberts) (The translator has reworded the second occurrence of the ST's lexical repetition and replaced it by having it rather than by 'experiencing it'; which would have retained the repetition.) – ولم يكن هناا سةوى مقاعةد قليلةة متنةا رة ومسةاحات فسةيحة خاليةةم10.a كحال الحافتت التي تستخدمها المطارات لنقل الركاب بين صالة المطارات .والطائرة 10.b - . . . I noticed that the seats were few and far between and interspersed with huge spaces, something like the buses used in airports to take the passengers from the terminal out to the airplane. (Roberts) (To avoid repetition, the translator has deleted the second occurrence of المطةةارات, thus producing terminal instead of 'airport terminal'.) 17 3.2.2 Explicitation in Translation (A) Examples from English-Arabic Translated Texts 11.a – It was a big, squarish frame house that had once been white, decorated with cupolas and spires, and scrolled balconies in the heavily lightsome style of the seventies . . . كانت الدار كايرة ومدورة وقد طليت في وقت ما بالطت األبيضم ومزخرفة11.b بالقاةةاب واألبةةراج والشةةرفات المدرجةةة علةةى أسةةلوب الطةةراف المنمةةاري الضةةخم (Abdulla( .والثقيل الوطأة الذي شاع في سانينات القرن التاس عشر (The English ST refers to the style 'of the seventies' without specifying of which century; the original text writer must have assumed that to be known to the ST readership. However, the translator, thinking of the requirements of the TT readership instead, must have deemed it necessary to clarify that the text refers to the seventies of the 19thC, and not the 20 th C., for example. He has consequently added the explanatory phrase, viz. القةرن التاسة عشةر, to specify the temporal setting of the text.) 12.a – And now Miss Emily had gone to join the representatives of those august names where they lay in the cedar-bemused cemetery among the ranked and anonymous graves of Union and Confederate soldiers who fell at the battle of Jefferson. 18 واآلن انتقلت اآلنسة اميلي لتلتحق بممثلي تلك األسما الجليلة الراقدة فةي- 12.b المقارة المحاطةة بأشةجار األرف التةي تطةل متأملةة مقةابر يوي الرتة النسةكرية الناليةةة ومقةةابر الجنةةود المجهةةولين الةةذين قةةاتلوا فةةي الحةةرب األهليةةة األمريكيةةة (Abdulla ) .وسقطوا في منركة جيفرسن (American readers, for whom the above text was originally written already know the history of the American Civil War; this is part and parcel of their cultural background information. Transferring the text from English to Arabic, however, puts the translator in a socio-cultural situation different from that of the original writer: the new readership of Arabic cannot be assumed to share the above-mentioned background information. The role of the translator as text mitigator would hence make it imperative that s/he interfere in favour of the reader by adding explanatory notes, together with the possibility of deleting some source culture-specific references sometimes.) 13.a – They called a special meeting of the Board of Aldermen. A deputation waited upon her, knocked at the door ... – دعةةةوا الةةةى عقةةةد اجتمةةةاع لشةةةيول الالةةةدةم فاننقةةةد وتقةةةرر أن يةةةذه اليهةةةا13.b )al-Aqqaad ) . . . فلما طرقوا بابها. . . مندوبون منهم (Joining sentences by various explicit sentence connectors has been found to be one of the strategies commonly used to realize the 'explicitation' tendency in translations. The motive behind it is believed to be the translator's desire to make the 19 target text easier to understand. This might explain why the translator has opted to join the two implicitly connected sentences of the above ST by adding the underlined as explicit joining words in the translation.) 14.a – "I received a paper, yes" Miss Emily said. "Perhaps he considers himself the sheriff . . . I have no taxes in Jefferson." . . قالت السيدة "اميلي" أجل لقد تسلمت ورقة ممن ينتار نفسةه الحةاكم-14.b )al-Aqqaad ( !ي ضرائ في جيفرسون ّ وم يلك ليس عل. (In 14.b above, the translator has added an explicit sentence connector. The function of the underlined words is to explicate the adversative logical relationship between the two sentences of the target text. This relationship is left implicit in the source text.) 15.a – Alive, Miss Emily had been a tradition, a duty, and a care; a sort of hereditary obligation upon the town, dating from that day in 1894 when Colonel Sartoris, the mayor – he who fathered the edict that no Negro woman should appear on the streets without an apron – remitted her taxes . . . – كانت النناية بالسيدة اميلي تقليدا وواجاا وضربا من الرعايةم وفرضةا15.b يتوار ه الناس في المدينة منذ عهد الكولونيةل سةرتوريس يلةك الحةاكم الةذي أصةدر االّ تخرج الةى الطريةق امةرأة مةن الزنةوج ببيةر ميدعةةم1894 أمره يات يوم عام )al-Aqqaad ( . . . وظل ينفي اميلي من الضرائ 20 (Had the translator retained the underlined pronominal 'her' of the source text in the translation, the reference of that personal pronoun in the Arabic translation would have been ambiguous: Does it refer to اميلةيor to ? امةرأة مةن الزنةوجThe translator has therefore opted to explicate the reference of the pronoun her by replacing it with اميلي.) (B) Examples from the Arabic-English Translations ربمةا العتقةادهم أن. ولم يكن يخطر باةال أحةد مةنهم التقةدم لمسةاعدتي. . . - 16.a .الحافتت عندنا هي على هذه الشاكلة أو لثقتهم في براعة قيادتي 16.b – It didn't seem to have occurred to any of them to offer me assistance, perhaps because they thought that all of "our" buses were as unconventional as this one, or perhaps because they had such confidence in my skill as a driver. (Roberts) (The reference of the deictic word هةذهin the phrase علةى هةذه الشةةةاكلةcan be problematic to retrieve for the reader. Consequently, the translator has decided to assume his responsibility as a text interpreter by introducing, in the target text, her understanding of the reference of the deixis in الشاكلة على هذه, viz. as unconventional as this one.) )Shunnaq( . فقد كانت له صداقة األنجليز وعساكرهم. وألنه الشي-17.a 17.b – Being in this privileged position, the Sheikh had close relations with the British soldiers. 21 (The title . الشةةيis culture-specific in Arabic with all the connotations and associations of power and prestige which go with this position. Such background information cannot, however, be taken for granted in the non-Arab socio-cultural context for which the translated text is intended. Hence, expansion for the sake of explicitation becomes necessary in the translation.) كان عساكر األنجليزي يقيمون عنده أياما وليالي حينمةا كةانوا ياةدأون- 18.a يصةر علةى. ولشدة صداقته لهم كان الشي.رحلة الاحث عن الثوار في جال الخليل .تقديم مناسل اللحم لهم 18.b – He used to invite them to his house whenever they passed by on their way to the Hebron Mountain, perhaps in pursuit of some rebels. The Sheikh would pander to the soldiers' every wish. He served them the choicest foods, usually 'mensef'. (Shunnaq) (The noun phrase مناسل اللحمrefers to one of the choicest dishes which is only served on special occasions in Jordan. This cultural specificity of the term prompted the translator to intervene, both by adding the phrase 'the choicest foods' and by adding a special footnote, in order to explain it to the new reader.4 The result is higher explicitness in the translated text.) ورث المشةةيخة والاندقيةةة والبض ة م فقةةد اعتةةاد أن يطةةو. وألنةةه الشةةي-19.a بسيارته اللةوري علةى الفتحةين فةي مواسةم الايةادرم يجمة شةواالت القمةح للفقةرا .واأليتام في القرى المجاورة 4 The translator has added the following footnote to explain the word Mensef: " 'Mensef' is a typical Jordanian dish composed of rice, meat and yoghurt" (Shunnaq 1996:51). 22 19.b – the Sheikh's raids on the villages at harvest time began as soon as he was given his title and position. Each time he made a raid, he would demand sacks of wheat, ostensibly for the poor and orphans in neighbouring villages. (Shunnaq) (The word 'ostensibly' in the translated text has no counterpart in the source text. Yet, its use in the translation does not seem to add any new meaning to that already understood from the source text. This is so since it would have most probably become clear to the text reader by now that the Sheikh was not in fact sincere in his claims about helping the poor. So, the translator has not really introduced anything new in the translation; he has only explicated what is already implied in the source text. The translator must have somehow felt it better to bring what is implicit to the surface.) في المرة األولىم قال أساوعين علةى هةذهم كنةت أقةود سةيارتيم وبرفقتةي- 20.a .فوجتي وأطفالي 20.b – The first time, two weeks prior to the bus incident, I'd been driving my car accompanied by my wife and children. (Roberts) (As in 16.a and 16.b above, the translator has clarified the reference of the deictic word هةذهby explicating its referent, viz. 'the bus incident'. The motive must have again been to alleviate the comprehension load in the translated text.) 23 4. Concluding Remarks 4.1. In order to investigate some aspects of the language of translation which are postulated to be typical of translated texts in general, the present study has analysed a number of translated texts both in Arabic and English. Close examination and comparison of the forty text fragments reported in Section 3 above has confirmed that the translations exhibit linguistic phenomena which support the two tested hypotheses concerning the presence in Arabic and English translated texts of both 'explicitation' and 'avoidance of lexical repetition'. 4.2. The above-mentioned results of data analysis attest tentatively to the specificity of the language of Arabic translated texts, which is the main theme of the paper. Although based on a small-scale data analysis, these results give credence to the Explicitation Hypothesis and the Repetition Avoidance Hypothesis as global linguistic regularities in translations irrespective of the languages involved. This is especially so since similar results have already been arrived at by a multitude of extensive research projects based on large-scale computerized corpora of translated texts in many other languages and in many parts of the world. 4.3. These, as well as many others of the above-mentioned common phenomena shared by translated texts, cannot only be explained by recourse to any, or both, of the two languages in question, viz. Arabic and English. Explanation, as was argued above, has to be sought in both trying to understand 24 the general cognitive processes involved in the translation process itself, as well as in the socio-cultural role of the translator as communicator, mediator, and text mitigator. 4.4. Research evidence derived from the analysis of Arabic texts translated from English, or vice-versa, can be of 'exceptional' significance for Translation Studies in general. This is so since Arabic and English belong to two typologically distant languages. The overwhelming majority of the studies conducted in the field so far are biased to comparing translations from English with those of other IndoEuropean languages, like French, German, Spanish, Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish. However, it is methodologically vital that the diversity of languages be taken into consideration since the results may be distorted otherwise. Consequently, both the research findings of comparing English translations with Finnish and Hungarian for example, as well as those with Arabic in the present paper, acquire special importance since all three languages are typologically distant from English. 4.5. As pointed out in 4.1 and 4.2 above, the results of the present study, although significant on their own, are based on small-scale data of Arabic-English and English-Arabic parallel texts. Larger corpora are required and other translation 'universals' need to be investigated if we were to arrive at results which are both more reliable and more comprehensive concerning the specificity of the language of Arabic translated texts. Moreover, Arabic translated texts need also to be compared with parallel translated texts from languages other than English. In addition to parallel corpora, it is of considerable importance that comparable data comprising translated and original texts within Arabic itself be 25 analyzed and contrasted so as to shed more light on the unique linguistic and textual characteristics of both types of text. 4.6. Research findings from worldwide extensive projects on the language specificity of translations, as well as the preliminary results of the present study, all seem to confirm that Arabic translated texts constitute a worthwhile and feasible field of academic research within the wider discipline of modern Arabic text linguistics. References Abdel-Hafiz, A. (2004). "Lexical Cohesion in the Translated Novels of Naguib Mahfouz: the Evidence from The Thief and the Dogs". http://www.arabicwata.org Abdulla, A. (2002). "Rhetorical Repetition in Literary Translation". Babel 47:4, 289-303. Abdulla, A. (1986). "وردة الةةى اميلةةي." النقةةد التطايقةةي التحليلةةي. Baghdad: Ministry of Culture & Information. al-Absi, I. (1992). " " الخةروج مةن دائةرة الصةمت. مختةارات فةي القصةة القصيرة. 7-9. Amman: al-Dustour Printing Press. al-Aqqaad, A. (1983). "وردة ألميلةةي. " ألةةوان مةةن القصةةة القصةةيرة. Cairo: Anglo-Egyptian Bookshop. Aziz, Y. (1997). "Translation and Pragmatic Meaning". Issues in Translation, ed. by A. Shunnaq, C. Dollerup, & M. Saraireh, 119-141. Irbid: Irbid National University. 26 Baker, M. (1993). "Corpus Linguistics and Translation Studies: Implications and Applications". Text and Technology: In Honour of John Sinclair, ed. by M. Baker, G. Francis & E. Tognini-Bonelli, 233-250. Philadelphia & Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Baker, M. (1992). In Other Words: A Coursebook on Translation. London & New York: Routledge. Berman, A. (2000). "Translation and the Trials of the Foreign". The Translation Studies Reader, ed. by L. Venuti, 284-297. New York: Routledge. Blum-Kulka, S. (2000). "Shifts of cohesion and coherence in translation". The Translation Studies Reader, ed. by L. Venuti, 298-313. New York: Routledge. Chesterman, A. (2004). "Beyond the particular". Translation Universals: Do they exist?, ed. by A. Mauranen & P. Kujamäk, 33-49. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Eskola, S. (2004). "Untypical frequencies in translated language: A corpus-based study on a literary corpus of translated and non-translated Finnish". Translation Universals: Do they exist?, ed. by A. Mauranen & P. Kujamäk, 83-99. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Faulkner, W. (1996). "A Rose for Emily". The Heath Introduction to Literature, ed. By A. Landy, 188-195. Massachusetts: D. C. Heath & Co. Frawley, W. (2000). "Prolegomenon to a Theory of Translation". The Translation Studies Reader, ed. by L. Venuti, 250-263. New York: Routledge. 27 Hatim, B. (1997). Communication Across Cultures: Translation Theory and Contrastive Text Linguistics. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. Hatim, B. (2001). Teaching and Researching Translation. London: Longmans. al-Khafaji, R. (1996). "Arabic Translation Alternatives for the Passive in English". Papers and Studies in Contrastive Linguistics, 31, 19-37. al-Khafaji- R. (2006). "In Search of Translational Norms: The Case of Shifts in Lexical Repetition in Arabic-English Translations". Babel, 52. al-Khafaji, R. (2001). "Punctuation Marks in Original Arabic Texts". Zeitschrift fur arabische Lingvistik /Journal of Arabic Linguistics, 40, 7-24. al-Khafaji, R. (1999). "Punctuation Transfer in Translated Arabic Texts". Turjman, 8, 2, 71-97. Laviosa, S. (1998). "Core Patterning of Lexical Use in a Comparable Corpus of English Narrative Prose". Meta, XLIII, 4, 1-15. Mauranen, A. (2000). "Strange strings in translated language. A study on corpora". Inter-cultural Faultlines. Research Models in Translation Studies I. Textual and Cognitive Aspects. ed. by M. Olohan, 119-141. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing. Nilsson, P. (2004). "Translation-specific lexicogrammar?: Characteristic lexical andcollocational patterning in Swedish texts translated from English". Translation 28 Universals: do they exist?, ed. by A. Mauranen & P. Kujamäk, 129-141. Amsterdam &Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Papai, V. (2004). "Explicitaion: A universal of translated text?". Translation Universals: do they exist?, ed. by A. Mauranen & P. Kujamäk, 143-164. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. al-Rimawi, M. (1992). ""الحافلةة تسةير. مختةارات فةي القصةة القصةيرة. 161-163. Amman: al-Dustour Printing Press. Roberts, N. (1996). "Bus Walk". A Selection of Jordanian Short Stories. 61-66. Amman: Dar al-Hilal. Schlesinger, M. (1991). "Interpreter Latitude vs. Due Process. Simultaneous and Consecutive Interpretation in Multilingual Trials". Empirical Research in Translation and Inter-cultural Studies. ed. by. S. Tirkkonen-Conduit, 147-155. Tubingen: Gunter Narr. Schäffner, C. & B. Adab. (2001). "The Idea of the hybrid text in translation: Contact and Conflict". Across Languages and Cultures, 167-180. Shunnaq. A. (1996). "Out of Silence". A Selection of Jordanian Short Stories. 43-51. Amman: Dal al-Hilal. Toury, G. (1995). Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Toury, G. (1980). In Search of a Theory of Translation. Tel Aviv: The Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics. Toury, G. (2000). "The Nature and Role of Norms in Translation". The Translation Studies Reader, ed. by L. Venuti, 198-211. New York: Routledge. 29 Toury, G. (1991). "What are descriptive translation studies into translation likely to yield apart from isolated descriptions". Translation Studies: The State of the Art. ed. By K. van Leuven-Zwart & T. Naajkens, 179-192. Amsterdam: Rodopi. Vanderauwera, R. (1985). Dutch Novels translated into English: The Transformation of a Minority Literature. Amsterdam: Rodopi