View/Open - DukeSpace

advertisement

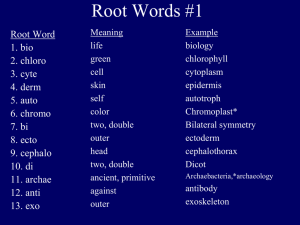

DEVELOPING THE COST OF LARGE CARNIVORE CONFLICT RAPID RESPONSE UNITS – A NAMIBIAN CASE STUDY by Melissa J. Bauer Dr. Luke Dollar, PhD, Advisor April 24, 2015 Master’s project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Environmental Management degree in the Nicholas School of the Environment of Duke University Executive Summary Namibia, in Southern Africa, is home to half of the world’s remaining wild cheetahs and provides valuable habitat for lions, leopards, brown hyena, spotted hyena and African Painted wild dogs. All six of these carnivore species find their population numbers dropping. Namibia represents a unique conservation problem, though, because in Namibia most of these animals (95% of cheetahs in the country, 87% of leopards, and 100% of African Painted Wild Dogs) exist on privately managed lands, outside of official protection. On these privately managed these animals come into large amounts of human/wildlife conflict where 96% of surveyed farmers claimed to experience some amount of livestock loss to carnivores within the last year and 60% of surveyed private land managers stating they would shoot any carnivore on sight, given the chance. In this climate real species conservation of these six species of carnivore will not be possible only operating on protected lands and working with private land managers is essential to species survival. To this end, a small team at the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation has been working for years to establish a network of private land managers working with the foundation on conflict mitigation strategies to frequency of fatal removal of carnivores from the landscape. In this study I went to Namibia to work the team. I worked to discover the conservation benefit this team was accomplishing and the costs involved. I then set to quantify the benefits achieved and cost involved in a return on investment scenario. I also used geospatial data from inside Namibia and the IUCN to identify where in the country of Namibia this mitigation might be needed most based on the number of carnivores species present through the country. I also set out to estimate the approximate cost anticipated if the team was to expand from its current operating area to being able to provide on-call mitigation help for the entire country of Namibia. As a result of my research in Namibia I found that the team is currently achieving an 80% reduction of the lethal removal of carnivores on private land my land managers for a price of $7.56/km2 over an area of 26,000 km2. This area encompasses 7% of all of the total land mass of the country of Namibia. Demonstrating demand, the number of outreaches requested is growing at 15-20% growth per year, completely organically without any advertising or the project. It was also determined that this service is needed, as at least one species of carnivore is reported to be present in all of Namibia that is currently already protected, in other words there is at least one species of carnivore present in all of the privately managed lands in the entire country of Namibia. The price for nationwide expansion team was found to be $816,412, of $2.31/km2. This price, when compared to the annual operating budget of other carnivore concerned NGOs, is very competitive, especially when considering the extremely high success rate. The nationwide figure is based on several assumptions and is theoretical number, but is very worthy of further exploration More research is needed in Namibia, especially in regards to species density maps and carnivore species population estimates. It is recommended that research into these areas is encouraged to the international scientific community and the Namibia national government. It is also recommended that the formation of a full time carnivore rapid response team is vigorously pursued by the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation, possibly being pitched to National Geographic’s Big Cat Initiative, a long standing funder of the foundation’s current project. It is also recommended that education aimed at private land managers and farmers be pursued by NGOs working within Namibia and the Namibian government to help build tolerance of carnivores by land managers before conflict arises. Table of Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………i Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Methods………………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Results……………………………………………………………………………………………………………9 Geospatial Analysis………………………………………………………………………………...9 Current Associated Benefits of Carnivore Conflict Mitigation Measures……10 Current Costs Associated with Carnivore Conflict Mitigation Measures……11 Financial Costs Anticipated if the Team was Expanded Nationwide…………12 Discussion…..…………………………………………………………………………………………………14 Recommendations…………………………………………………………………………………………16 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………..17 References…………………………………………………………………………………………………….18 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………………………………….20 Introduction In our modern world, with shrinking wildlife habitat and increasing human populations, large carnivores have proven to be among the most difficult groups of mammals to conserve, (Mech, 1995). Their populations have been dramatically reduced during the last 200 years, with their large home range requirements and predatory behavior on both wild prey and livestock bringing them in constant conflict with human populations, (Nowell & Jackson, 1996). In Namibia in Southern Africa this presents a unique challenge where six large carnivore species, i.e. cheetah Acinonyx jabatus, leopard Panthera pardus, spotted hyena Crocuta crocuta, brown hyena Hyaena brunnea, lion Panthera leo and African Painted wild dog Lycaon pictus, are all listed as decreasing by IUCN Red Lists, (IUCN, 2014). At the same time the large majority of the distributions of these species fall outside of protected areas, (Riggo R. et all, 2012, Lindsey et. al, 2013). Finding ways to promote coexistence between people and carnivores on private land has thus proven to be essential for the six large carnivore species. 43% of Namibia, or 356,533 km2, is managed by freehold farming and tourism, (Mendelson, 2006). The same area provides the major source of carnivore habitat, especially for cheetah and leopard (Durant et al, 2008, Hentshel et Al, 2008). Namibia is known to have the largest population of cheetahs occurring in the wild in the world, (Marker et al 2003), yet, possibly counter intuitively at the same time, a recent study found that protected areas encompass less than 5% of the wild cheetah population there, (Lindsey et al, 2013). These animals are living on the privately help farmland. Leopards are well known to be the most widely distributed of the wild carnivores in Namibia, however it is estimated that only 13% of the leopard’s potential range in this country exists within protected areas, (Marker and Dickman, 2005). Without the cooperation of land managers responsible for this land, successful conservation of these species cannot be maintained only in government national parks and protected areas. In addition, the continual growth of conservancies, from four in 1998 to 59 in 2012 suggested the diversifying of growing wildlife ownership, and suggests that human and carnviores will come into contact more frequently in the future, and by a larger portion of the Namibian human population, (Mosimane et al, 2013). While found throughout private land in Namibia, occurrence varies among species and area within the country. In a recent large survey study researchers found the following distributions: Cheetahs had the widest occurrence of the large carnivores, widely distributed throughout the northern, central and south western parts of Namibia, all in commercial farming areas. Leopards were almost just as widely distributed, though less densely, and also extended their range into the far South of the country. Brown hyenas were found to have a similar wide distribution like the leopards, but were even more sparsely distributed. Spotted hyenas were found in the northern, central, and southwestern parts of Namibia, once again in commercial farm land but persisted on very few farms in those areas. By far the most limited were lions and wild dogs with low occurrences, and only in the extreme north east and north respectively, (Lindsey et al, 2013). In the same study showing at least one carnivore species present throughout almost all of the Namibian farmland, tolerance among farmers towards carnivores varied between species. Farmers were most tolerant of leopards, and were found to be least tolerant of lions, wild dogs and spotted hyenas, (Lindsey et al, 2013). Farmers, however, who also wanted four other large carnivore species only desired lions and wild dogs. This suggests that special circumstances, such as tourism or trophy hunting income, are required for tolerance towards these species, (Lindsey et al, 2013). The human intolerance towards the large carnivores, while sometimes based on unfounded perceptions and historical prejudices, often represent real financial motivations. A survey of 147 Namibian farmers from communal conservancies was published in Environmental Conservation in 2013. Communal conservancies make up 16% of the total land of Namibia, and almost half of all the freehold farming and tourism un-protected land, (Rust and Marker, 2013). In the survey approximately one-third of all goat and sheep farmers reporter making zero profit from their stock or lost more stock to predators annually than were replaced by births. Also of the 147 farmers surveyed, 96% had suffered at least some livestock depredation within a year of the survey, (Rush and Marker, 2013). These costs shed light on one of the key problems associated with carnivore existence on private lands in Namibia: the benefits disproportionally go to people not having to pay the associated costs. This is an inherent problem with some of the standing wildlife policies in Namibia. In an environment lacking an over-arching approved and effective human- wildlife conflict mitigation policy, the costs of conflicts are paid by local residents. However, many of the benefits of wildlife populations go to the Namibian government and international visitors, (Mosimane et a, 2013). This disproportionate distribution of costs and benefits can further enhance resentment and hostility towards carnivores. Unfortunately in the absence of human tolerance for the conservation of these large carnivores, lethal control of the populations is often widespread on Namibian farmland, most often without remorse or denial. This killing of carnivores isn’t limited to one species or another. For example, 15% of farmers in a recent study reported to shoot leopards on sight, given the chance, and without proof of livestock predation, and upwards of 60% of survey respondents shoot the species given suspect, not proof, of predation, (Stein et al 2010). In the same study it was found that at least 29 lions per year are killed on lands bordering Etosha National Park, with much higher numbers of kills expected but not recorded, and one rancher interviewed bragged of shooting more than 200 cheetahs in his lifetime, (Lindsey et al, 2013). What’s interesting is that there doesn’t have to be actual physical or economic conflict with carnivores for the species to be viewed as “conflict animals,” that need to be eliminated. Schuman, Walls and Harley did a random sample of commercial farmers from several cultural groups and both sexes. More than half, or 52.4%, of the commercial farmers reported that carnivores are either a ‘big’ or ‘very big’ problem. That problem was perceived when no, or little, livestock predation haven taken place. 56.1% of farmers stated carnivores have presented as a problem when the only evidence they had of carnivore ‘conflict’ occurred after only sighting a carnivore itself, (Schumann et al, 2012). The perception of a problem, regardless of whether livestock depredation had taken place, is a sufficient motivator for famers to desire the removal of all carnivores from their land. In many cases it has been found that simply seeing carnivore or its tracks was motivation enough to take action against the animals, (Schumann et al, 2012). In this climate, it is not surprising that despite intensive conservation efforts overall carnivore species are declining, (IUCN, 2014). As stated before the IUCN lists all six aforementioned species are at risk or declining. Lions are estimated to have an approximately 30% species population reduction over the past two decades, approximately three lion generations, (Bauer et al, 2012). Cheetahs have disappeared from 67% of their historic range on the continent of Africa, and at least a 30% reduction in their population is suspected of the past 18 years, or 3 generations, (Durant et all, 2014). Leopards still remain wildly in sub-Saharan Africa, but have been disappeared from at least 36.7% of their historical range and are listed as near threated and decreasing, (Hentschel et all, 2008). African Painted wild dogs, a species that historical data indicates were formally distributed throughout sub-Saharan Africa, is in serious danger listed as endangered by the IUCN. Also listed as still declining currently African Painted wild dogs are estimated as only having approximately 1,400 mature animals left, (Woodroffe and Sillero-Zubiri, 2014). Further complicating matters, wild dogs have been reintroduced to Etosha National Park six different times, all unsuccessful, and are therefore completely dependent on private lands for survival. (Woodroffe and Sillero-Zubiri, 2014). Once endemic to almost the entire country of Namibia brown hyena populations in the country are now estimated to only be between 522-1187 animals and are considered decreasing, (Wiesel et al, 2008). While spotted hyena is listed as ‘least concern’ by the IUCN, the is a continuing decline in populations both outside protected areas and due to persecution through shooting, trapping and poisoning and habitat loss, (Honor and Mills, 2008). While these numbers might paint a bleak picture, they also present a unique opportunity. Expanding conservation work beyond that national parks and striving for higher cooperation with private land managers and farmers could possibly achieve real, measurable effects on carnivore populations. Research has shown that carnivores can coexist with high human densities if an appropriate management policy if put in place and enacted. Linnell, Swenson and Anderson published an article in Animal Conservation arguing that where effective regulation of human behavior there should be no strong correlation between human density and carnivore extension. Their research implicates that large carnivore conservation, to be effective, requires establishment of effective wildlife management structures, (Linnell et al, 2001). In the study of costs associated by carnivore depredation in which 96% of survey responders reported at least some livestock depredation, herders and livestock guardian dogs were not often used. When livestock guardian dogs were used, however, almost all of the animals utilized were small or medium sized dogs, not an adequate size for deterring large predators, (Rush and Marker, 2013). In the Schumann et al study from Oryx 40.8% of farmers wished to have all carnivores removed from their farmland, but in contrast famers who looked upon carnivores as having an ecological role on the farms were less likely to want all carnivores removed, carte blanch, (Schumann et al, 2012). This in of itself provides a wonderful educational opportunity as it is well documented that without top predators controlling the populations of smaller predators, there may be a small predator population release, causing more damage than good. This problem is currently being faced throughout Namibia and South Africa where jackal and caracal populations are rising after the extirpation of large carnivores across many commercial farming areas. This is being found to cause significant damage to sheep and goat farms, (Rust and Marker, 2013). In another example of where further education is needed, perceived loss of livestock attributed to carnivores may be higher than actual losses to emerging farms, as many have little knowledge of carnivore ecology and behavior and are not able to correctly identify causes of livestock loss (Schumann et at, 2012). There have been many published studies that confirm the tendency of famers to exaggerate losses or to attribute livestock losses to carnivore depredation regardless of the loss can be verified to that cause or not (Marker et al, 2003). In contrast, when livestock management is applied often livestock losses to carnivores can be reduced. When combined with general ecological knowledge training, management training can prove to be effective, as demonstrated, people who are more knowledgeable about carnivores tend to be more tolerant (Rust and Marker, 2013). The challenge lies is shifting the conversation with farmers away from carnivore removal towards proactive livestock management techniques. This would require training in carnivore ecology and kill identification, to replace inaccurate perceptions of loss with accurate verification, and training in livestock management techniques. In addition farmers and land managers need to have information made accessible to them about different way to recoup financial losses, including tourism and trophy hunting, and in a last resort lethal control, in a judgment free setting. One initiative, the N/a ‘an ku se Carnivore Conservation Research Program lead by researcher Florian Weise, utilizes a model with focus on building long-term relationships with farmers and free-hold land managers by providing them with multiple co-habitation options. Mr. Weise and N/a ’an ku se staff carry out intensive and repeat consultations with the people responsible for on-site carnivore management on private farms, most of which have reached out to government and other NGOs in the past, (F. Weise, personal communication, 2014). Despite disappointing results from government sources and other NGOs these land managers still show a willingness to tolerate and co-exist with carnivores, and a motivation towards non-lethal carnivore management whenever possible, (F. Weise, personal communication, 2014). Some of the options discussed in these consultations include education about improved livestock husbandry, capture-mark-release and subsequent joint monitoring of carnivores (especially cheetahs and leopards), or translocation of conflict animals as a last resort. These consultations are provided yearround, on a 24-hour on-call basis, free of charge to the land managers. In the six years since this program has been initiated in 2008, Mr. Weise and his team have conducted 250+ consultations, all with land managers who have reached out in an effort to find successful methods of cohabitation with carnivores. On some properties 20+ consultations have been provided by Mr. Weise and his team, aiming to fine-tune carnivore management strategies (F. Weise, personal communication, 2014). This method has proven successful, as demonstrated by large (and often repeat) demand for the services, and also by data possessed by Mr. Weise including the difference in numbers of carnivores trapped and killed reported by the land managers for the two years before their initial consultations with N/a’ an ku se and for the number of carnivores persecuted post consultations. These results are consistent with research suggesting that when a sense of ownership over human-wildlife conflict is achieved by land managers, and an understanding of the role of carnivores, more positive attitudes of the carnivores by land manages can be achieved, (Schumann et al, 2012). These long-term relationships build on research that finds that farmers with involvement in active carnivore management, instead of removal, and education about conservation promotes more positive attitudes regarding carnivore problems and less human-carnivore conflict, (Schumann et al, 2012). While marked conservation results and stronger relationships can be found around N/a’ an ku se research sites, due to logistic constraints vast parts of Namibia’s private farmlands are left with little effect by this effort. For effective nation-wide conservation of large carnivores using this approach, I propose the formation of a full time carnivore response team. This team would build upon the work of Mr. Weise by offering immediate response and on-site consultations to all private land managers in Namibia in response to perceived or actual conflict with carnivores - free of charge, and with the possible effect of both encouraging positive cohabitation between humans and carnivores and making marked conservation efforts in Namibia for all six large carnivore species there. Methods Research into building a carnivore rapid response team in Namibia was broken down into three basic research questions: How cost effective are the practices currently being implemented by the N/a ‘an ku se Carnivore Conservation Research Program and what kind of results are they experiencing? Would this proposed team be needed for the entire country? What are the anticipated costs if this program were to be expanded from the current size to coverage for all of Namibia that would need it? To answer these questions time was spent in Namibia at the N/a ‘an ku se Carnivore Conservation Research Program at their headquarters outside of Windhoek, Namibia during the summer of 2014. Time was spent collecting data and doing informal interviews with the staff there about the program. Data was collected in regards to financials of the organization and costs associated with the various projects there including incoming grants from organizations such as National Geographic’s Big Cat Initiative. Informal interviews were conducted with Mr. Florian Weise, the chief researcher associated with the project, Dr. Rudie van Vurren, the co-found and president of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation, Stuart Munro, a long time field researcher associated with the project and Dara Barrett, the head of the finance of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation. The informal interviews consisted of gathering expert opinion on the current project’s status, delegation of the foundation’s incoming grant money as associated with this specific project, delegation of the foundation’s existing resources as associated with this specific project, and anticipated additional resources needed to expand the project. Informal interviews were also conducted with conservation experts back in the United States about anticipated resources needed to expand the project, including with Dr. Luke Dollar of National Geographic and Dr. Stuart Pimm the Doris Duke Chair of Conservation Ecology at Duke University. The resulting information from these interviews was used to assemble a list of current costs associated with the project, the current success rates being achieved by the team and a list of resources that would need to be assembled for successful nationwide implementation of the project. Back into the United States, geospatial data was assembled from the online Namibian database http://www.the-eis.com/ and from IUCN about the known ranges of the six carnivore species. Geospatial data was also collected showing the locations of the already protected land in Namibia. This geospatial information was assembled to build visual tools, maps, identifying ranges of the six considered carnivore species on non-protected land. The ranges were combined to show what parts of Namibia had the highest number of carnivores species present. Species density, in addition to species presence, data was attempted to be incorporated into this project but unfortunately after an exhaustive search it was concluded that this data was not available. Also back in the states a database of 14 different resources that are needed for a carnivore rapid response team was built. This database consisted of the amount of the resource currently being utilized, the amount of the resource that would be needed to cover the entire country, and the costs of acquiring that resources if acquired at the current time in Namibia. Actual costs accrued were used when that information was available from the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation. However, when the prices were not able to be sourced from the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation, or those prices were deemed unrealistic, quotes were sought from outside the organization. Quotes for resources were requested from in-country vendors in Namibia, at current market prices, whenever possible. When a range of prices within quotes were found a final price of the mean of the spread of quotes was used in final financial calculations. Those quotes, along with results from the informal interviews about resources currently being utilized on the project were combined to assemble a close as possible current estimate of the associated costs currently being spent on the carnivore response team. The same quotes, combined with the results from the interviews in Namibia and in the United States were used to estimate the anticipated price of such a team with full nationwide Namibian utilization. Finally, a price comparison was sought between the price of this team and other conservation efforts currently in use, both in Namibia and locally here in North Carolina. The annual operating budget from the Cheetah Conservation Fund in Namibia, the International Snow Leopard Trust and the Carolina Tiger Rescue were obtained from their publically available tax records. In addition, the combined amount of the salaries of the top three paid employees of the World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, the Wildlife Conservation Society and Panthera for 2013 were obtained from those organization’s publically available tax records. A comparison was made between our estimated total annual operating budget for the nationwide utilized carnivore rapid response team and those two sets of financial numbers. Results Geospatial analysis Geospatial representations of ranges for the 6 considered species were assembled onto one map to find an consideration area for of the proposed team. Areas that were already considered protected were taken out of the considered area and excluded. Figure 1 to the right shows the resulting map. As shown, there is reported to be at least one considered carnivore species present in all areas Figure 1. Carnivore Range Distribution in Namibia of Namibia outside of protected areas. There also appears to be the highest density of number of species in the northern and eastern parts of the country. Current Associated Benefits of Carnivore Conflict Mitigation Measures Through in country interviews with the management and staff of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation I was able to obtain information about the history, current implication and reported effectiveness of the carnivore mitigation work they were doing. As reported by Dr. Rudie van Varren, president of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation, Florian Wiese, head of the research department 2006-2015, Stuart Munro, assistant/current director of the research department, and Dara Barrett, CFO of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation I was able to assemble the following information. The N/a ‘an ku se Foundation has been working with farmers on the reduction of the lethal removal of carnivore species on the farmer’s land for 7.5 years. This program has not been officially formalized within the foundation, rather is one of several missions of the foundation and is not a stand-alone project. Detailed records have been kept by Florian Weise as to the number of farmers him and his team have worked on. Mr. Weise would not fully release those records to me as they are the basis for his upcoming PhD thesis but he would give me highlights and is anxious to include research involved in this Master’s Project into his PhD. In the past 7.5 years the team working out of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation has worked with 221 different land managers, reporting a total of 375 separate lethal carnivore removals before working with the mitigation team. Those 221 different land managers represent a total area of approximately 26,000 km2 of land. This represents approximately 7% of the total area of Namibia. The farmers report an 80% reduction in the lethal removal of carnivores on their lands after working with the mitigation team. The outreach/mitigation team at N/a ‘an ku se Foundation have been experiencing a 15-20% growth in the program during the last 7.5 years. If the same growth rate is assumed to continue, it would take approximately 14 years before the study area of 26,000 km 2 would expand to the entire country of Namibia. Current Costs Associated with Carnivore Conflict Mitigation Measures Resources that were either currently being utilized, or were anticipated to be needed if the program were identified. Those 14 things were: Staffing (later broken down into prime responders and an office manager) 4 wheel drive double-cab large bed truck able to carry at least two people and a carnivore cage Vehicle maintenance including fuel, insurance, maintenance, wear and tear and tires Flying costs if a property could only be reached by plane Office space rent Water Utility service for office Space Electric Utility for office space Office Phone for office space GPS carnivore collars and that are able to be access for daily downloadable location points Anticipated Housing and care of animals if the animals needed to be translocated Laptop, including internet service that can be accessed in the field for collar location downloads Satellite phones and service Carnivore trap cages After identifying those 14 different costs, quotes for each item were located. Those quotes, and their associated sources can be found in the appendix of this report. The current utilization and anticipated need for those resources were then calculated. Through in country interviews with the management and staff of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation I was able to obtain information the amount of resources currently being utilized in their farmer outreach/mitigation work. As reported by Dr. Rudie van Varren, president of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation, Florian Wiese, head of the research department 2006-2015, Stuart Munro, assistant/current director of the research department, and Dara Barrett, CFO of the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation I was able to assemble a list of the current assets being deployed to achieve that 80% reduction in the lethal removal of carnivore species. In regards to the 14 different associated costs: The mitigation measures do not currently include a full time staff member. It is currently being handled part time by a few different staff members. When added together that is estimated to be about ½ of one full time prime responders responsibilities and billable time. Several different vehicles are used on mitigation calls, as the team currently uses whatever vehicle is available when needed, but when added together that equals approximately the full time utilization of one truck. The team is currently housed within the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation's headquarters on their own property. Therefore rent, electricity, water and an office phone should not be considered a current cost. All calls are being driven into, not flown, so flying costs need not be considered at this time. This, however, would change when the mitigation expands nationwide, especially to the northeastern part of Namibia as this part of the country has the highest number of species present, but is mostly inaccessible by roads. While the team has had to translocate animals due to farmer mitigation, the associated animals have almost exclusively ended up on the N/a ‘an ku se property. This associates the animal with one of the foundation’s other missions and therefore the costs should not be associated with current mitigation costs. However, this could not be sustained on a nationwide level so translocation costs would have to be considered in the future. The foundation does not currently have a satellite phone. While the foundation does have carnivore trap cages and laptops, they are used in all the different missions of the foundation, not just this one specific project, and therefore weren’t considered in the current cost figure. The team is currently employing about 40 GPS carnivore collars with associated download fees for mitigation strategies. All of the above factors, and their associated quotes were aggregated to come up with a final cost of the mitigation being used to achieve an 80% reduction in the lethal removal of carnivores over 26,000 km2. I estimate that costs to be $196,639.90, or $7.56/km2. Financial Costs Anticipated if the Team was Expanded Nationwide The 14 costs different resources were then expanded to estimate the anticipated yearly cost of the team that would be needed if the team were being utilized nationwide. After consulting expert opinion both inside Namibia and here at Duke University the following list of assumptions were constructed: If current utilization encompassed ½ of one full time member for 7% of the country than expansion 13x for the entire country would need 7 full time members. This could best be accomplished by having 6 full time prime responders and 1 full time office manager. Office space would be needed, though not large as most of the work would be done either on the phone on location on the private land. The office would best be located in Windhoek, Namibia’s capitol, as the city has the best infrastructure in the country and is also centrally located within the country. Costs for electricity, water, rent, and an office phone would therefore need to be considered. Each responder would need a truck, dedicated carnivore trap cage, laptop, and satellite phone Approximately 6 calls per year would need to be flown into. This would allow the team to access parts of the country with high numbers of species present and are not easily accessible by roads. These assumptions and the associated quotes were once aggregated to determine an final estimated anticipated cost. This figure came to $816,412.70 in 2015 United States Dollars. When divided out by the square kilometers of all the private lands in Namibia, this figure comes to an estimated anticipated cost of $2.31/km2 to achieve the same level of 80% reduction in lethal carnivore removal. Discussion In a country with such conservation potential as Namibia, finding successful conservation mitigations is vital to the survival of species. Conservation measure in southern Africa have been going on for decades, though, and aid organizations do not have an unlimited budget. It is, therefore, of the upmost important to discern not only the most effective conservation measures in terms of ecological value, but also in terms of return on investment. This ensures that for every dollar spent in species conservation carnivores, and other species in peril, are getting the most amount of “bang for the buck.” The anticipated estimated annual budget of $816,412 includes a lot of assumptions, but it also has factors built in that could make this figure quite lower. For example, built into this number is the purchase of all of the resources at once, a circumstance highly unlikely to take place. Several resources, including trucks, laptops and satellite phones would not need to be purchased every year and would be acquired gradually as the team grew. It’s also important to recognize the limitations of this estimate. While the team is currently accomplishing an 80% reduction in lethal removal, that success is primarily being achieved in the middle parts of Namibia. As shown through the geospatial analysis, when the team moved into the more northeastern and northwestern parts of the country it would be bound to have more conflict dealing with lion and African Painted Wild Dogs. The mitigation strategies most successful in cheetah and leopard mitigation might have to be adjusted in these geographic areas. In addition, as discussed earlier, while range distributions were able to be built into this study for the 6 species of carnivores, it was impossible to take into account species density throughout the ranges. This could have significant impacts in the amounts of conflict that would arise and further adjustments would become critical. Despite the financial figure’s limitations it makes for an interesting comparison between this theoretical number and the money already being spent by other conservation organizations. 2 Figure 2: Comparison between proposed annual operating budget for carnivore rapid response team as compared to other carnivore-concerned NGOs and 3 comparison Figures show a between the estimated cost of the carnivore rapid response team covering the entire country of Namibia as compared to the annual operating budget of other carnivore-related NGOs and the estimated cost compared to the top three salaries of some of the conservation Figure 3: Comparison between proposed annual operating budget for carnivore rapid response team as compared to top 3 salaries international respectively. conservation NGOs organizations, largest Both figures show that, while highly theoretical, a team that is achieving such high lethal removal success rates is has such a high rate of return that it is worth of exploration and expansion, at least on a trial basis. Recommendations In a country with limited ecological knowledge, more research is needed in this area. For example, the first leopard density database and map is just now being assembled and will probably take years to assemble. Species density geospatial analysis is critical not only for leopards but all of the discussed carnivore species to be able to address the areas most in need of mitigation. Further, while population numbers are estimated for all six species of carnivores discussed, those numbers are highly debated. While conservation is undeniably needed for all species of carnivores, until true population numbers can be established it’s difficult to measure the population benefits of reduced fatal interactions between these animals and land owners. In addition, while it does not fall under the scope of this project, it is worth noting that the carnivore rapid response team does not come into action until there is already conflict between private land managers and carnivores. Perhaps this problem could be addressed before conflict arises. As discussed in the introduction surveyed farmers view carnivore as a problem even before livestock is killed. Education into the behaviors of these animals could help build tolerance among the land managers and perhaps might build an understanding that killing animals on sight can sometimes make predation worse instead of better. Despite limitation and further research needed, it is strongly recommended that if funding can be secured, forward movement on this proposed carnivore rapid response team is pursued. As a current grantee to National Geographic’s Big Cat Initiative, further funding should be explored to build the team, at least to the point of one full time staff member, housed either at N/a ‘an ku se or independently. If positive growth in this program is maintained the possible conservation benefits to the carnivore species in Namibia could be unprecedented. Acknowledgements A special thank you to everyone involved in this project, including everyone at the N/a ‘an ku se Foundation and the National Geographic’s Big Cat Initiative, especially Florian Weise, Rudie van Vurren, Stuart Munro and Dara Barret. A very special thank you goes out to Dr. Luke Dollar, my advisor on this project for providing expert opinion and direction and without whom completion would not have been possible, and Dr. Stuart Pimm who helped make the project possible and provided invaluable feedback. In addition, thanks go out to Karen Kirchoff and the entire CPDC staff at the Nicholas School of the Environment, the Nicholas School’s Environmental Internship Fund, and the Nicholas School’s International Internship Fund for providing funding that makes the research trip to Namibia possible. References Bauer, H., Nowell, K. & Packer, C. 2012. Panthero Leo. In: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.1 www.iucnreslist.org. Downloaded on 16 July 2014. Durant, S., Marker, L., Purchase, N., Belbachir, F., Hunter, L., Packer, C., Breitenmoser-Wursten, C., Sogbohossour, E. & Bauer, H. 2008. Acinonyx jabatus. In: The IUCN Red List of Threated Species. Version 2014.1 www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 14 July 2014. Hentschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Markter., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser-Wursten, C. 2008. Panthera pardus. In: The IUCN Red List of Threated Species. Version 2014.1 www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 14 July 2014 Honer, O., Holekamp, K.E. & Mills, G. 2008. Crocuta crocuta. In: The IUCN Red List of Threated Species. Version 2014.1 www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 14 July 2014 Lindsey, P, Havemann, C, Lines, R, Palazy, L, Price, A, Retief, T, Rhebergen, T, Van der Wall, C (2013). Determinants of Persistence and Tolerance of Carnivores on Namibian Ranches: Implications for Conservation on Southern African Private Lands. PLos ONE 9(1): e52458. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052458 Linell JDC, Swenson JE, Anderson R (2001). Predators and people: conservation of large carnivores is possible at high human densities if management policy is favourable. Animal Conservation (4): 345-349. Marker LL, Dickman AF (2005). Factors affecting leopard (Panthera pardus) spatial ecology, with particular reference to Namibian Farmlands. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 35 (2): 105-115. Marker LL, Mills MGL, Macdonald DW (2003). Factors influencing perceptions of conflict and tolerance toward cheetah on Namibian farmlands. Conservation Biology 17: 12901298. Mech, L.D. (1995). The challenge and opportunity of recovering wolf populations. Conservation Biology, 9: 857-868. Mendelsohn, John. (2006). Farming Systems in Namibia. Research & Information Services of Namibia. ABC Press, South Africa. Mosiame AW, McCool S, Brown P, and Ingrebretson J. (2013). Using Mental Models in the anlaysis of human-wildlife conflict from the perspective of social-ecological system in Namibia. Fauna & Flora International, Oryx 48(1), 64-70 Nowell, K. & Jackson, P. (1996). Wild cats: status survey and action plan. Gland, Switzerland, IUCN. Riggo R, Jacobson A., Dollar, L., Bauer H., Becker, M., Dickman A., Funston P, Grooom R, Henshcel P, de Lonh H, Lichtenfield L, Pimm S (2012). The size of savannah Africa: a lion’s (Panthera leo) view. Biodiversity and Conservation DOI 10.1007/s10531012-0381-4. Rust NA, Marker, LL (2013). Cost of Carnivore Coexistance on communal and resettled land in Namibia. Environmental Conservation 41(1) : 45-53. Stein AB, Fuller TK, Damery DT, Sievert L, Marker LL (2010). Farm Management and Economic Analysis of Leopard Conservation in North-Central Namibia. Animal Conservation 13: 419-427. Schumann B, Walls JL, Harley V (2012). Attitudes towards carnivores: the views of emerging commercial farmers in Namibia. Fauna & Flora International, Oryx. 46(4), 604-613. Wiesel, I., Maude, G., Scorr, D. & Mills, G. 2008. Hyaena brunnea. In: The IUCN Red List of Threated Species. Version 2014.1 www.iucnredlist.org Downloaded on 14 July 2014 Woodroffe, R. & Sillero-Zubiri, C. Lycaon pictus. In: The IUCN Red List of Threated Species. Version 2014.1. www.iucnredlist.org Downloaded on 14 July 2014. Appendix Figure A1: Map of Protected Areas of Namibia Figure A2: Known Lion Range in Namibia Figure A3: Known Leopard Range in Namibia Figure A4: Known Cheetah Range in Namibia Figure A5: Known Brown Hyena Range in Namibia Figure A6: Known Spotted Hyena Range in Namibia Figure A7: Known African Painted Wild Dog Range in Namibia Table A1: Table of Costs Associated with Carnivore Rapid Response Team Current Resource Use Covering 26,000 sq. km with 80% reduction in lethal carnivore removal Salary of Office Manager Not currently needed Salary of Prime Responder 1/2 Total Salary of head of research department currently allocated to this specific project Vehicle (needs to be double-cab, large bed 4wd truck) Total of 1 full time truck use currently associated with this project Associated Costs Anticipated Resource Needed for Nationwide Coverage Anticipated Associated Costs (in 2015 values) N/A Equivalent of one full time worker (might have to be two part time workers as is a 365/day a year job) to answer phones and sent out daily collar updates. Expert opinion is anticipated fair salary would be 50 NAD/hr. 8 hours paid a year *365 days/year * 50 NAD/hr. = 146,000 NAD/ year 1/2 Total Salary of 240,000 NAD/year = 120,000 NAB/year Aggregated Expert Opinion is that by expanding program 13 times, would need 6 full time responders, each at 240,000 NAD/year 6 * 120,000 NAD/year = 720,000 NAD/year 1 full size 4wd off-road truck = 300,000 NAD 1 truck per responder, this would be if purchased them all at the same time, which in practicality wouldn't probably be the case 6 trucks * 300,000 truck = 1,800,000 NAD Notes These estimates are based on estimated salary expectations as should reasonably expected for this line of work in Namibia. These numbers are from Flo and Rudie who did a survey of conservationists and land managers in Namibia and their willingness to pay Sent out e-mails to around 25 dealerships in Namibia asking for quotes on 3/4/15, based on averages from quotes received Vehicle maintenance such as gas, insurance, repairs, possible auto club membership, vehicle registration, spare tires, etc. Flying costs Rent of Office Space in Windhoek 30,000 km driving/year, Naankuse calculates their mileage including fuel, maintenance, and tires, wear and tear, and insurance at 12 NAD/km). 30,000 km is the number of miles associated with this project in 2014. area currently operating in, can drive into all calls N/A as currently operating out of Naankuse's headquarter, therefore costs already part of existing Naankuse infrastructure 30,000 km * 12 NAB/km = 360,000 NAD/year Assuming same mileage per responder as current usage for all 6 responders 30,000 km * 12 NAB/km * 6 responders = 2,160,000 NAD/year Assuming same mile per prime responder as current usage. N/A Assuming, based on informal expert interviews a need for 6 fly-in calls/year If we estimate 6 flying call outs, for far-flung locations, a year that would come out to a total of NAD 84,000 The cost of flying with the plane comes in at approximately NAD 3500 per flying hour. The average flying time to go on a call-out to dart & collar a carnivore appears to be about 4 hours. N/A Assuming would need relatively small office space in Windhoek. Took average rent published by Namibian government for 100 m2 of office space (2013 published data) N$65-$120/m2 * 100 m2 office = N$6,500 N$12,000 year. Average is 9,250 NAD/year assuming 100 m2 space, with no rent increase. Figures from "Cost of Doing Business" from MET Namibia Water for Office Space in Windhoek N/A as currently operating out of Naankuse's headquarter, therefore costs already part of existing Naankuse infrastructure Electricity for Office Space in Windhoek N/A as currently operating out of Naankuse's headquarter, therefore costs already part of existing Naankuse infrastructure Office Phone for Office Space in Windhoek N/A as currently operating out of Naankuse's headquarter, therefore costs already part of existing Naankuse infrastructure N/A 40 collars/year currently in use 40 collars * $3,300 per collar for collar plus daily download fees (quote from Siri track) = $132,000 US Collars and download fees of such N/A N/A N$19,47 – N$46,63 per month for 15 mm to 20 mm 8 12 months = N$233.64 - N$559.56 year Basic charge: N$48.00 - N$228 per month *12 = N$576 - N$2,736 / year 100 collars + daily download fees: $US 3,300 * 100 = $333,000 Sir track ARGOS GPS collars Average is 396.60 NAD/year assuming lowest amount of water consumption, Figures from "Cost of Doing Business" from MET Namibia Average is 1,656 NAD/year Probably would be on the low end, as using not much electricity. Assuming no increase in electricity charges through year 3, Figures form "Cost of Doing Business" from MET Namibia $389 NAD/mo plus one time set-up fee of 218 NAD for 300/min 1.5 GB internet at 150 SMS a month for 24 month package - total per year is 4,886NAD Quote from MTC, can adjust if more use of data is needed $330,000 US Gathered expert consensus that entire expanded team would need approx. 100 new collars a year as new animals + replacement costs. Housing and care of animal if needed to be translocated, until time that it can be released Laptop including internet service that can be accessed in the field for collar location downloads and communication of those locations to farmers Phone that can be used in rural areas of Namibia, possibly satellite phone and service all translocations associated currently filter into Naankuse Foundation's ecotourism model already part of existing Naankuse infrastructure don't currently have this N/A Gathered expert consensus is would need average of 3 leopard and 2 cheetah translocations per year N/A Need one laptop per responder and one for office. Obviously this accounts for buying them all at the same time, which is not what would happen N/A Would need six satellite phones, one for each responder. Once again, in practicality these would not all be bought at the same time 3 leopards @ $US3,140 = 2 cheetahs @ US$6,898 = $US 23,216 (This figure is probably a VERY, VERY high estimate) Cost of 5 translocations a year: 3 leopard, 2 cheetah, based on average translocation costs based on Flo's paper "Financial Costs of Large Carnivore Translocations Accounting for Conservation" 7 laptops @ NAB$4,599 * 7 = NAD 32,193 Quote from Gadget Namibia for Proline "Smart" Notebook including PROLINE W945TU N2830 14" 2GB HD 500GB Sata. Their laptops go up to Intel Celeron N2800, Windows 8.1 Bing, their prices go up to NAD$17,857 for 13" Apple MacBook Pro Purchase 6 phones @ US$1,720 plus 400 min each/month @US$1.25/min. 400 min/mo *12 months * 2 phones= US$46,320 Quote from rentasat.com.za for Iridium cell phone. Recommended from MET as the only kind of phone with true nationwide coverage. (Rent a Satellite South Africa) Carnivore cages currently do not have any cages specifically allocated for this project $ 196,639.90 Total Divided by coverage Price per sq. km. for 80% reduction in lethal removal of carnivores due to human/wildlife conflict with private land managers and farmers N/A Expert opinion agrees would need approx. 6 cages year so each responder can have one. Most farmers having worked with already have trap cages themselves. Currently covering 26,000 sq. km. divided by 26,000 $ 7.56 Approximately 354,00 sq. km. privately managed in Namibia 6 cages * 12,000 ZAR = 72,000 ZAR From research found that most cages are handmade in country so hard to price. Flo paid 12,000 ZAR/piece for custom traps made in 2014 so going with that figure. $ 816,412.70 Based on 4/19/2015 exchange rates 1.00 USD = 12.0668 NAD/ZAR divided by 354,000 $ 2.31 Price per sq. km drops significantly, mainly due to significant drop in collars needed/sq. km, based on lots of assumptions though