Ocean Jigsaw Reading

advertisement

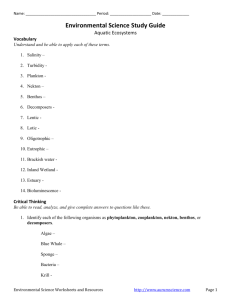

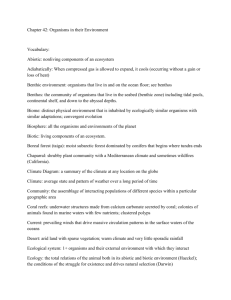

Box One: Marine Life Forms What living organisms are found in any one place in the ocean is determined by the environment at that place: temperature, pressure, and the amount of light in the water. Marine biologists have classified ocean-dwelling organisms into 3 main types: plankton, those that do not swim or that swim weakly, nekton, those that swim, and benthos, those that are bottom dwelling. Organisms living in the intertidal zone are adapted to being repeatedly exposed to air and to the action of waves. Most marine life is found in the neritic zone, where there is enough light for photosynthesis. In deeper zones there is little or no light. Animals in these zones have such adaptations as light-producing organism, high sensitivity to pressure and very sensitive eyes. Plankton These organisms are drifters, carried place to place by the wind, waves, and current. Plankton are microscopic organisms that float freely with oceanic currents and in other bodies of water. Plankton is made up of tiny plants (called phytoplankton) and tiny animals (called zooplankton). Plankton is the first link in the marine food chain; it is eaten by many organisms, including mussels, fish, birds, and mammals (for example, baleen whales). Phytoplankton are primary producers (also called autotrophs). As the base of the oceanic food web, phytoplankton use chlorophyll to convert energy (from sunlight), inorganic chemicals (like nitrogen), and dissolved carbon dioxide gas into carbohydrates. Zooplankton are microscopic animals that eat other plankton. Nekton Animals that swim or move freely in the ocean are nekton. Nekton come in all shapes and sizes. Fish of all varieties are a major part of this group, as are reptiles like sea turtles and sea snakes, and mammals such as seals, whales, or porpoises. Invertebrates, such as jellyfish, sea worms, squids, shrimps and scallops complete the group. Nekton live in shallow and deep ocean waters. Most nekton eat zooplankton, other nektons, or they scavenge for waste. Benthos The benthos live on the ocean floor. There are four main groups: burrowing, attached, crawling, and swimming animals. Starfish, oysters, clams, sea cucumbers, brittlestars and anemone are all benthos. Most benthos feed on food as it floats by or scavenge for food on the ocean floor. Box 2: The Intertidal Zone The intertidal area (also called the littoral zone) is where the land and sea meet, between the high and low tide zones. This complex marine ecosystem is found along coastlines worldwide. It is rich in nutrients and oxygen and is home to a variety of organisms. The organisms that live here are adapted to huge daily changes in moisture, temperature, turbulence (from the water), and salinity. The littoral zone is covered with salt water at high tides, and it is exposed to the air at low tides; the height of the tide exposes more or less land to this daily tide cycle. Organisms must be adapted to both very wet and very dry conditions. The turbulence of the water is another reason that this area can be very difficult one in which to survive - the rough waves can dislodge or carry away poorly-adapted organisms. Many intertidal animals burrow into the sand (like clams), live under rocks, or attach themselves to rocks (like barnacles and mussels). The temperature ranges from the moderate temperature of the water to air temperatures that vary from below freezing to scorching. Depressions on the shores sometimes form tide pools, areas that remain wet, although they are not long-lasting features. The salinity of tidepools varies from the salinity of the sea to much less salty, when rainwater or runoff dilutes it. Animals must adapt their systems to these variations. Some fish, like sculpin and blennies, live in tide pools. Animals that live in the littoral zone have a wide variety of predators who eat them. When the tide is in, littoral organisms are preyed upon by sea animals (like fish). When the tide is out, they are preyed upon by land animals, like foxes and people. Birds (like gulls) and marine mammals (like walruses) also prey on intertidal organisms extensively. The littoral zone is divided into vertical zones. The zones that are often used are the spray zone, high tide zone, middle tide zone, and low tide zone. Below these is the sub-tide zone, which is always underwater. Spray Zone: This area is dry much of the time, but is sprayed with salt water during high tides. It is only flooded during storms and extremely high tides. Organisms in this sparse habitat include barnacles, lice, periwinkles, and whelks. Very little vegetation grows in this area. High Tide Zone: Also called the Upper Midlittoral Zone and the high intertidal zone. This area is flooded only during high tide. Organisms in this area include anemones, barnacles, brittle stars, crabs, green algae, mussels, sea stars, snails, and some marine vegetation. Middle Tide Zone: Also called the Lower Midlittoral Zone. This chaotic area is covered and uncovered twice a day with salt water from the tides. Organisms in this area include anemones, barnacles, crabs, green algae, mussels, sea lettuce, sea palms, sea stars, snails, sponges, and whelks. Low Tide Zone: Also called the Lower Littoral Zone. This area is usually under water - it is only exposed when the tide is unusually low. Organisms in this zone are not well adapted to long periods of dryness or to extreme temperatures. Some of the organisms in this area are abalone, anemones, brown seaweed, crabs, green algae, hydroids, isopods, limpets, mussels, sea cucumber, sea lettuce, sea palms, sea stars, sea urchins, shrimp, snails, sponges, surf grass, tube worms, and whelks. Box 3: The Neritic Zone The Neritic zone lies above the continental shelf. It is part of a larger zone called the pelagic zone. It extends from the low-tide mark outward from the seashore to where the depth of the water reaches 200 meters (656 feet). This water is lit by sunlight and relatively shallow. The majority of sea life lives in this zone because it has well-oxygenated water, low pressure, and a fairly stable temperature. Neritic waters are penetrated by varying amounts of sunlight, which permits photosynthesis by both planktonic and bottom-dwelling organisms. The zone is characterized by relatively abundant nutrients and biologic activity because of its closeness to land. The shallow waters of the coastal zones occupy just 10 per cent of the total ocean area, but are home to 98 per cent of marine life. Coarse, land-derived materials generally form the bottom sediments, except in some low-latitude regions that favor production of calcium carbonate sediments by such organisms as algae, bacteria, and corals. Within the neritic zone, marine biologists must also identify the following: The infralittoral zone is the algal dominated zone; it goes to maybe 5 meters below the low tide mark. The circalittoral zone is the region beyond the infralittoral, it is dominated mostly by sessile (fixed in one place; immobile) animals such as oysters. The subtidal zone is sometimes defined as the shallower region of the neritic zone close to the shore. The neritic zone is permanently covered with generally well-oxygenated water, receives plenty of sunlight and has low water pressure, moreover, it has relatively stable temperature, pressure, light and salinity levels, making it suitable for photosynthetic life. In particular, the benthic zone (ocean floor) in the neritic is much more stable than in the intertidal zone. The above characteristics make the neritic zone the location of the majority of sea life. Sea turtles, dolphins, coral and colorful fish make up some of the organisms found in this zone. Phytoplankton and floating Sargasso make up most of the photosynthetic life here. Zooplankton, such as free-floating microscopic foraminiferans or small fish and shrimp feed on the phytoplankton (and one another). Box 4: The Oceanic Zone The oceanic zone begins in the area off shore where the water measures 200 meters (656 feet) deep or deeper. This zone is also a part of the pelagic zone. It is the region of open sea beyond the edge of the continental shelf and includes 65% of the ocean’s completely open water. The oceanic zone has a wide array of undersea terrain, including crevices that are often deeper than Mount Everest is tall, as well as deep-sea volcanoes and ocean basins. While it is often difficult for life to sustain itself in this type of environment, some species do thrive in the oceanic zone. The oceanic zone is subdivided into the photic, and aphotic zones. There are further subdivisions that we will not review at this time, just know that there are more zones. The photic zone, also called the sunlit zone, receives enough sunlight to support photosynthesis. The temperatures in this zone range anywhere from 104 to 27 °F. 90% of the ocean lies in the aphotic zone into which no light penetrates. Water pressure is very intense and the temperatures are near freezing range 32 to 43 °F. Oceanographers have divided the ocean into zones based on how far light reaches. All of the light zones can be found in the oceanic zone. The photic zone is the one closest to the surface and is the best lit. It extends to 200 meters and contains both phytoplankton (microscopic autotrophs) and zooplankton (very tiny heterotrophs) that can support larger organisms like sharks, tuna, mackerel, and sea turtles. There are creatures however, which thrive around hydrothermal vents, or geysers located on the ocean floor that push out super heated water that is rich in minerals. These organisms feed off of chemosynthetic bacteria, which use the super heated water and chemicals from the hydrothermal vents to create energy in place of photosynthesis. The existence of these bacteria allow creatures like squids, hatchet fish, octopuses, tube worms, giant clams, spider crabs and other organisms to survive. Animals that live in the deep sea must be able to survive cold temperatures, an increase in pressure, and dark waters. Past 200 meters, not enough light penetrates the water to support life, and no plant life exists. Some fish, like the viper fish and hatchet fish have sharp fangs and large mouths to help them catch food. Due to the total darkness in the zones past the photic zone, called the abyssal zone, many organisms that survive in the deep oceans do not have eyes, and other organisms make their own light with bioluminescence. Often the light is blue green in color, because many marine organisms are sensitive to blue light. Two chemicals, luciferin and luciferase, react with one another to create a soft glow. The process by which bioluminescence is created is very similar to what happens when a glow stick is broken. Deep-sea organisms use bioluminescence for everything from luring prey to navigation.