Confronting Africa*s Health Challenges

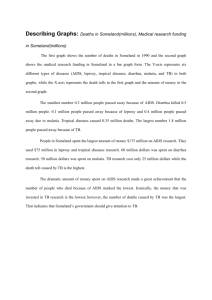

advertisement

Confronting Africa’s Health Challenges Jeremy Youde Department of Political Science University of Minnesota Duluth jyoude@d.umn.edu 1 Are sick people as big a threat to the stability and security of sub-Saharan Africa as arms proliferation and civil conflict? Health and disease have emerged as major themes in analyzing the state of politics and security in sub-Saharan Africa in recent years. Political scientists have paid increasing attention to health and disease in general, challenging and refining notions of their importance to the global community, and much of this attention has focused on Africa. This attention has had some beneficial elements, such as highlighting the importance of sub-Saharan Africa’s importance to international politics more broadly. While there appears to be a growing consensus on the importance of health and disease for African politics and security, understandings and interpretations of that importance vary widely. We find ourselves in a situation where most people agree that health matters, but large disagreements exist over how and why it matters. Resolving, or at least understanding, the nature of these differences has important implications for both academic analysis and policymaking. This paper seeks to offer an understanding of the current state of the debate over the relationship between health and security in Africa. To do this, I will examine how the role of health in security politics has changed, how scholars and policymakers have assessed the nature of this relationship, and the consequences they have foretold. The first section of the paper will examine the debates over the relationship between health and security in Africa. Security, particularly in the post-Cold War era, remains a highly contested term, and much of the tumult centers on the appropriateness of incorporating nonmilitary elements into a broader understanding of security. In particular, it will examine the ongoing debates over expanding the realm of security to include non-military threats such as health. The second section focuses on the nature of the challenge posed by health and infectious disease to sub-Saharan Africa. Initial reports suggested that disease posed a direct threat to 2 African states, but more recent work presents a more nuanced and less linear relationship. The third section will examine the hypothesized political, economic, and military consequences of high rates of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. HIV/AIDS has received the vast majority of attention within the larger debates about health, so examining these hypothesized relationships can be quite instructive. The fourth section will discuss which issues have been overlooked in the current conceptualization of African health and security. Not all diseases are treated equally, and this unequal treatment has major consequences. The final section will re-examine the basic question of whether the security framework is most appropriate for addressing health problems and inequities in sub-Saharan Africa. Does health matter for security? With the demise of the Cold War, security studies scholars grappled with questions of the nature of security in the new international environment. Traditional understandings of security focused exclusively on military and physical threats within a state-centric framework. A number of researchers questioned the applicability of this paradigm in the post-Cold War era. While the military-focused, state-centric model may have been appropriate in a bipolar world, they challenged the model’s usefulness in a world facing numerous serious non-military threats (such as environmental degradation, refugee flows, illicit drugs, crime, and food scarcity) with only one superpower (Kolodzeij 1992). Calls for incorporating non-traditional threats under the rubric of ‘security’ also called for greater attention paid to the threats faced by individuals rather than states. For most of the world’s inhabitants, the threat of nuclear warfare was far more remote and less threatening than the exhaustion of their land’s capability to sustain agriculture or the eruption of a civil war in their country. 3 At the same time, many scholars argued that incorporating new issues into security studies would dilute the term’s meaning. Walt argues that security studies should remain focused on its traditional realm, “the study of the threat, use, and control of military force” (Walt 1991: 212). He and his colleagues argue that this not only provides more intellectual coherence to the field, but also that it maintains a high level of analytical and methodological rigor. Adding nonmilitary issues to security studies would also decrease the field’s ability to offer useful policy suggestions to government officials (Walt 1991: 213). In a now-seminal article, Deudney explicitly argued against the expansion of security into new realms, such as environmental degradation (Deudney 1990). While not denying the challenges environmental changes pose to the international community, including it and other ‘new’ security threats led to inappropriate policy suggestions and engendered us-versus-them thinking that directly contradicted the international cooperation necessary to address these problems. While this debate emerged in the pages of international relations journals, the AIDS epidemic entered the public consciousness. International organizations began to create programs dedicated to preventing the disease’s spread, offering treatment (though such options were almost non-existent in the late 1980s and early 1990s), and raising public awareness of the disease. As researchers gathered more and more information about the extent of AIDS’ spread in some countries and noted the demographic trends associated with the disease, some began to call AIDS a threat to economic development, governance, and national security. In the final year of the Reagan Administration, the US government commissioned a report which forecasted future trends and potential threats to American national security. It noted that AIDS could weaken national militaries, heighten concerns about foreign visitors spreading the disease, and pose large financial and social costs. Noting the already-high infection rates in Central Africa, the authors 4 wrote, “Given the dearth of trained people in most of the African societies, the projected early morbidity and early demise of the managerial and political elite suggest that a significant degree of political and economic instability may arise in the next 5 years” (Population and Development Review 1989: 598). The emergence of AIDS and the potential threats it posed coincided with the emergence of the human security paradigm. With the end of the superpower rivalry of the Cold War, a movement developed to redefine conceptualizations of security away from its traditional statecentric focus on military and physical concerns and toward a more individual-level conception of security. The United Nations Development Program, in particular, embraced this redefinition of security. In its 1994 Human Development Report, the authors defined human security as: It means, first, safety from such chronic threats as hunger, disease, and repression. And second, it means protection from sudden and hurtful disruptions in the patterns of daily life—whether in homes, in jobs, or in communities (United Nations Development Program 1994: 22). UNDP then went on to disaggregate security into seven distinct realms: economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political security. By so doing, UNDP hoped to change the conversation within the international community, shift the referent of security away from the state and toward the individual, and develop an all-encompassing, integrative redefinition of security. As this broadened definition of security took hold and gained prominent advocates, health gradually became incorporated into the realm of security issues (McInnes 2008: 276-277). Advocates of human security emphasized its relevance to the real challenges threatening most people in their daily lives. Nuclear weapons did not cause most people a great deal of concern or worry on a regular basis; not being able to provide for their families did. Infectious 5 disease fits into this conception of security, as extensive illness prevents people from working, wipes out household savings, and threatens the social fabric of society. That said, there exists no clear consensus of how to define health security. In some instances, its definition focuses on protection against microbial threats. At other times, the definition centers on new global challenges that lack adequate international responses, the emergence of new actors into the security arena, or direct links with a government’s specific foreign policy interests (Aldis 2008: 371-372). While the larger debates over the merits of human security and its impact on international policymaking go beyond the scope of this article1, understanding the basic terrain of the debate is critical for understanding the literature on health and security. Most writers who have addressed the health/security linkages at least make reference to human security, and some explicitly situate the connections between AIDS and security within the human security framework. Even writers who disavow the utility of human security make references to the literature. While the usefulness of the human security paradigm is an active area for debate, it has become de rigueur to make at least passing references to it within the AIDS and security literature. While many of these debates focus on contemporary concerns, we should be mindful of the numerous historical examples of where ill health has undermined national and international 1 See Liotta (2005), MacFarlane et al. (2006), and Paris (2001), among others, for more comprehensive treatments of the debates over human security and its place within the field of security studies. 6 security in its traditional sense. One scholar remarks, “It is curious that the pernicious effects of epidemics on states and societies should be well established in the domain of science and yet be paid little attention in the domain of political science” (Price-Smith 2009: 35). Thucydides’ (1980) account of the Peloponnesian War pays particular attention to the deleterious consequences of an epidemic on Athens’ ability to fight. Spreading rapidly and killing mercilessly, this unnamed disease undermined the city-state’s ability to field an effective military while also weakening the social, economic, and political structures necessary to fight Sparta. McNeill (1977) exhaustively details how disease epidemics thwarted leaders’ abilities to conquer new territories or expand their realms. Indeed, he ties the demise of the Byzantine Roman Empire in the 6th Century CE directly to the so-called “plague of Justinian”—which may have been the first known manifestation of bubonic plague in Europe (McNeill 1977: 126). Zinsser saw a direct link between plague and societal insecurity, arguing that “panic bred social and moral disorganization; farms were abandoned, and there was a shortage of food; famine led to displacement of populations, to revolution, to civil war, and, in some instances, to fanatical religious movements which contributed to profound spiritual and political transformations” (Zinsser 1934: 129). Crosby (1986) argues smallpox (inadvertently) allowed Hernando Cortes to conquer the militarily-superior Aztecs because the disease ravaged Tenochtitlan and severely undermined the Aztecs’ faith in their government and religious structures (Crosby 1986: 200). Fastforwarding to the 20th Century, Crosby (2003) argues that the influenza pandemic spread particularly among military members during World War I, which weakened their fighting capabilities. Using German and Austro-Hungarian mortality data, Price-Smith finds a distinct and direct correlation between the rise in influenza-related mortality and the collapse of their war 7 efforts. Not only did influenza weaken and kill those fighting, but it also prevented necessary war materiel from getting to troops in a timely manner (Price-Smith 2009: 68-75). State of disease in sub-Saharan Africa Infectious diseases pose a particular threat to sub-Saharan Africa. The World Health Organization’s Global Burden of Disease provides valuable statistical data to demonstrate this sad fact. Strikingly, Africa is the only region in the world where infectious and communicable diseases are responsible for the majority of deaths. In 2004, Africa experienced 11.3 million deaths. Of these, 7.7 million—68 percent of all deaths on the continent—were attributable to communicable diseases, maternal conditions, and nutritional deficiencies (World Health Organization 2004). Infectious diseases, like AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, collectively caused 4.85 million deaths—63 percent of deaths from communicable diseases, and 43 percent of all deaths. AIDS was the leading killer among infectious diseases, causing 1.65 million deaths, followed by diahrreahal diseases (1.00 million), malaria (806,000), and tuberculosis (405,000). Noncommunciable conditions, such as cancer, stroke, heart disease, and diabetes, took 2.80 million lives in Africa in 2004 (25 percent of all deaths). To put Africa’s disease burden into a global context, no other region of the world had a majority of its deaths come from communicable illnesses. Globally, communicable diseases were responsible for 17.97 million out of 58.77 deaths worldwide in 2004—just over 30 percent. Noncommunicable conditions, on the other hand, caused 35.01 million deaths, or nearly 60 percent of the worldwide total. Among the rest of the world’s regions, the Eastern Mediterranean has the highest percentage of deaths from communicable conditions at 38.5 percent of its 2004 deaths, followed by South-East Asia (36.9 percent), Americas (13.6 percent), Western Pacific 8 (12.9 percent), and Europe (6.0 percent) (World Health Organization 2004). These stark figures hammer home the reality that Africa’s communicable disease burden more than twice as high as the world average and far exceeds all other regions in the world. Sub-Saharan Africa has the unfortunate distinction of being home to the greatest number of potential international health concerns. Between September 2003 and September 2006, the World Health Organization verified 685 events of potential international health concerns. These concerns include infectious diseases that have the potential to spread internationally and become epidemics. Of these 685, Africa was the source of 288—42 percent of all incidents over this three-year period (World Health Organization 2007: x). Further, sub-Saharan Africa is responsible for 42 percent of the 10.2 million annual deaths in children under 5. This gives the continent a child mortality rate 7 times that seen in Europe (Boschi-Pinto et al. 2009). Burkle (2009) argues that 75 percent of all disease epidemics arise from conflict situations, and that the majority of these conflict situations have emerged on the African continent. He cites problems like cholera and dysentery in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, outbreaks of Marburg hemorrhagic fever in Angola during the civil war there, and leprosy in Sudan. “Poverty and preventable diseases still plague many parts of the globe. Sub-Saharan Africa remains one of the most severely affected [regions],” explains Aitsi-Selmi (2008: 597). While HIV/AIDS receives the bulk of attention when discussing health and disease in Africa (and will be the subject of a later section), it is not the infectious disease plaguing the continent. A brief review of some of the other infectious disease burdens facing Africa will demonstrate the myriad of challenges. One striking fact about the distribution of death in sub-Saharan Africa is that younger people are at the highest risk. In 2004, 46 percent of all deaths in sub-Saharan Africa occurred 9 among those under the age of 15, while 20 percent occurred in those over 60. By contrast, those under 15 accounted for only 1 percent of deaths in wealthy countries and 24 percent in Southeast Asia (World Health Organization 2004: 8). The World Health Organization has compiled the ten leading causes of disease burden, using a measure of DALYs (disability-adjusted life years). Each DALY is the equivalent of one year of full health, and is the sum of years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lost due to disability due to a health condition. This measure allows us to see the burden of both diseases that cause early death with little disability and diseases that cause high levels of disability but little death (World Health Organization 2004: 40). As of 2004 (the most recent year for which statistics are available), the top three causes of DALYs were HIV/AIDS (12.4 percent of DALYs), lower respiratory infections (11.2 percent), and diaherreal diseases (8.6 percent). These three were responsible for nearly one-third of sub-Saharan Africa’s DALYs. Other leading causes of disease burden included malaria, tuberculosis, and protein-related deficiencies (World Health Organization 2004: 45). Table 1 shows the complete list of DALYs in sub-Saharan Africa, while Table 2 shows the leading causes of death in sub-Saharan Africa among different age groups. [INSERT TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE] [INSERT TALE 2 ABOUT HERE] Let us examine some of the leading causes of disease burden in sub-Saharan Africa. HIV/AIDS Twenty-two million people in sub-Saharan Africa are HIV-positive. This is approximately two-thirds of all the cases of the disease worldwide. During 2007, UNAIDS 10 estimates that 1.9 million more Africans contracted the virus, while 1.5 million died of AIDS (UNAIDS 2008). Infection rates vary widely throughout sub-Saharan Africa. While some countries like Senegal and Niger have infection rates of approximately 1 percent of adults, three countries—Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland—have adult HIV infection rates of over 20 percent. The vast majority of cases in sub-Saharan Africa are transmitted via heterosexual intercourse. As a consequence, sub-Saharan Africa has high rates of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Reports estimate that ninety percent of the world’s two million HIV-positive children live in sub-Saharan Africa (AVERT 2009a). Transmission also occurs among men who have sex with men and through the use of unclean needles (due either to injection drug use or reusing unsterilized needles in health care facilities) (UNAIDS 2007: 9, 13-15). The demographic breakdown of HIV cases in sub-Saharan Africa reveals three fascinating patterns. First, the epidemic is concentrated overwhelmingly among women. Sixtyone percent of all infections in the region are among women (Asburn et al. 2009: 1). This is a significant deviation from the epidemic as a whole, which has a nearly even split between males and females (UNAIDS 2008). Second, there exist age disparities within infection rates. Women 15-24 are the most vulnerable to HIV infection, in some countries with twice the infection rates than men 15-24 (Ashburn et al. 2009: 1). Men infected with HIV in Africa tend to be older. Third, deaths due to AIDS have had a dramatic effect on life expectancy rates in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Demographers estimate that sub-Saharan Africa as a whole would have an average life expectancy of 61 years today without the presence of AIDS. Due to AIDS, though, average life expectancy has dropped to 47 (AVERT 2009b). The effects are even more pronounced in countries with high prevalence rates. Swaziland, with the highest adult HIV prevalence rate, has a life expectancy at birth of 31 years—less than half the projected rate in the 11 absence of AIDS (CIA 2009). In many countries, this means that life expectancy rates today are lower than they were when the country achieved independence. Lower Respiratory Infections Lower respiratory infections (LRIs) include pneumonia, emphysema, and acute bronchitis. These are diseases that target the trachea, bronchi, and lungs and are generally more serious than upper respiratory infections. They can be either viral or bacterial in origin. In 2004, LRIs caused 1.417 million deaths in sub-Saharan Africa, more than any other region. Further, they are the leading cause of mortality in children under the age of 5, and the number of deaths from LRIs increased between 2002 and 2004. Though access to antibiotics has increased in recent years, many children in Africa lack access to health care facilities to receive treatment in a timely manner. Further, the overuse and abuse of antibiotics has led to an increase in antibioticresistant LRIs (Lim et al. 2006). Treating these cases puts an even greater burden on alreadystretched health care resources. Diarrheal Diseases Diarrheal diseases include diarrhea, cholera, and dysentery. Diarrheal diseases caused more than 1 million deaths in sub-Saharan Africa in 2004, accounting for nearly half of all such deaths worldwide. While these illnesses can be viral, bacterial, or parasitic in origin, they are primarily transmitted via contaminated water. Water may be contaminated with human or animal feces in areas with inadequate sanitation systems. The recent cholera epidemic in Zimbabwe, for example, is a direct result of the collapse of the country’s sanitation infrastructure due to its dire economic situation. NGOs working on diarrheal diseases note that, despite the heavy disease 12 burden caused by these illnesses, they receive far less funding than other infectious diseases. Governments spent $1.5 billion on sanitation between 2004 and 2006—one-tenth the amount devoted to HIV/AIDS and one-third spent on malaria, even though neither disease kills as many children as diarrhea, cholera, and dysentery (Eagle 2009). Malaria Malaria is a vector-borne disease caused by parasites transmitted by infected mosquitoes. Once infected, the parasites colonize the liver and infect red blood cells. Fever, vomiting, and headache appears 10 to 15 days after exposure. Malaria can become fatal if it interrupts the supply of blood to vital organs. Each year, between 300 and 500 million cases of malaria occur worldwide, causing between 1.5 and 2.7 million deaths annually. Ninety percent of these cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa (Nchinda 1998: 398). In 2004 alone, malaria caused 806,000 deaths in sub-Saharan Africa—90.7 percent of all deaths worldwide from the disease. During the 1950s and 1960s, the World Health Organization led an international effort to eradicate malaria, primarily through vector control strategies relying heavily on DDT and other insecticides. While this strategy initially showed some promise, it quickly became apparent that mosquitoes were developing resistance to the insecticides and common treatment methods. As a result, the number of cases of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa between 1982 and 1995 was four times as high as those between 1962 and 1981 (Packard 2007: 175). Today, malaria is responsible for 20 percent of all mortality in children under 5, and every country in Africa (except for Libya) is considered endemic for the disease. WHO figures cite malaria as causing up to 40 percent of public health expenditures, 30 to 50 percent of hospital admissions, and up to 60 percent of outpatient visits in the region (WHO 2009b). Thirty-five sub-Saharan African 13 countries today have intensive malaria, and economic analysis suggests that malaria causes these countries—which are already largely poor—grow 1.3 percent less annually. Cutting the rate of malaria by 10 percent, on the other hand, could allow these states to grow by 0.3 percent (Gallup and Sachs 2001). Tuberculosis Tuberculosis is a surprisingly common infection, with approximately one-third of the world’s population having been infected with the bacilli that cause the disease. In most cases, the immune systems keep the bacteria in check and people feel no ill effects. Approximately 10 percent of these latent infections become active, characterized by chronic coughs, weight loss, chest pain, fever, and night sweats. Without treatment, tuberculosis can kill more than 50 percent of its victims. The treatment regimen entails a six-month course of antibiotics, taken on a consistent basis. Tuberculosis killed 405,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa in 2004, with more than 2 million additional people falling ill with the disease (WHO 2005). As with malaria, tuberculosis rates in sub-Saharan Africa have increased dramatically in recent years. Between 1990 and 2003, the rate of infection in the region more than doubled, from 149 cases per 100,000 population to 343 cases. During this time, nearly every other region in the world experienced a decrease in tuberculosis rates (Chaisson and Martinson 2008: 1089). Much of the blame for startling increase in tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa belongs to HIV. Tuberculosis is the most common coinfection among HIV-positive persons, as their immune systems cannot keep tuberculosis bacilli walled off any longer. As a result, 30 to 40 percent of HIV-positive adults die of tuberculosis (Chaisson and Martinson 2008: 1089). Rising infection rates also put the general population at greater exposure to the disease, as it is spread through 14 droplets in the air caused by coughs and sneezes. Each infected person not receiving treatment can infect an additional 10 to 15 people (WHO 2007b). The other major cause of increased tuberculosis rates is inadequate access to treatment. Failure to diagnose an active infection early or inconsistent access to drugs has led to forms of tuberculosis which are increasingly resistant to treatment. These new strains, known as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) are far more difficult and expensive to treat. Recent studies suggest that, on average, two percent of the tuberculosis cases in sub-Saharan African states are MDR-TB (Amor et al. 2008). XDR-TB was first discovered in South Africa in 2006, and the country reported more than 300 cases of the disease by the end of that year (Singh et al. 2007). Security implications of disease in Africa With growing debates over the nature of security, a growing number of scholars and policymakers have wondered about the ethical considerations of expanding or restricting the definition of security. Securitization theory, popularized by the Copenhagen School, can play a particularly important role here. Elbe calls it “the only systematic scholarly study of the ethical implications of widening the security agenda to include an array of non-military issues” (Elbe 2006: 124), while Huysmans calls it the most original and controversial contribution to security studies in years (Huysmans 1998: 480). Securitization theory focuses on how and why certain issues become security concerns in the first place. A wide range of non-military issues, like HIV/AIDS, environmental degradation, poverty, hunger, and global warming, could conceivably be security issues, but not all will successfully make it to the national security agenda. What determines which issues succeed? 15 Securitization theory focuses on the performative nature of speech acts. Calling something a security issue or security threat constitutes a performative speech act, in which the words used to describe something themselves function as an activity. Describing an issue as a security issue gives that issue a special social quality for policymakers. “By saying the words, something is done,” according to Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde (1998: 26). The designation itself brings with it certain connotations, and implies a certain sort of response. It also affects how other parties view the issue and its place on the political agenda. In essence, the act of securitizing an issue (by calling it a security issue) effectively forms an agreement among political actors. Waever notes that the security label “does not merely reflect whether a problem is a security problem, it is also a political choice” (1995: 65). Choosing to designate something as a security issue (or as a development issue, or a human rights issue, or any other type of issue) is thus be a political tool to advance particular goals and aims. The major implication of securitization theory is that we cannot use some sort of empirical criteria to determine which issues are security issues. We instead have to look at the intersubjective understandings of a particular issue to understand whether it holds a place on a nation’s security agenda. It is less about any particular qualities of the issue itself, and more about how the issue is discussed, debated, and presented in public. For securitization theory, an issue becomes securitized when: 1. securitizing actors (like political leaders) declare that 2. a referent object (something threatened, such as the state or the military) is 3. existentially threatened by some force and therefore requires 4. emergency measures to protect against the threat (Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde 1998: 24-36). 16 Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde emphasize that securitization requires all four criteria to be successful. These criteria also show that not all issues that undergo the securitization process will necessarily be securitized. The audience is quite important, too, as they have to accept the argument. The securitizers must convince their audience that this threat poses such an existential challenge to them that the government must be allowed to take extraordinary measures—and they must do so in a way that resonates within a given political context. The government must be able to suspend the rules of normal politics in order to save the lives of the populace. Successful securitization must be audience-centered and fit within an understood and accessible context (Balzacq 2005). If audiences do not accept the need to adopt emergency measures or doubt that an issue existentially threatens the referent actor, then it does not become a security issue. Securitization, then, becomes a political choice on the part of the government2. Securitizers choose, for some reason, to elevate a given issue into the realm of security. Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde themselves caution against securitizing non-military issues, arguing that it represents “a failure to deal with issues as normal politics” (1998: 29). Reaching for 2 A fascinating and contentious debate has emerged in recent years over securitization’s normative content and the methods of desecuritizing an issue. Some have argued that securitization is a political act by politicians, and that securitization merely provides a framework for analysts to understand those moves (Taureck 2006, Waever 2000). Others have claimed that analysts using the securitization framework co-constitute and legitimate the securitizers’ efforts (Aradau 2004, 2006). Similarly, the meaning and methods of desecuritization remains underspecified in most Copenhagen School literature (c.a.s.e collective 2006: 455), and debates exist as to desecuritization’s implications for politics (Aradau 2004). 17 extraordinary powers signals a failure by existing political institutions to accommodate this new issue in a timely and beneficial manner. The discussions of securitizing health and disease in Africa have focused almost exclusively on HIV/AIDS. Though recent analyses have broadened this focus to include diseases like malaria and tuberculosis, the analytical gaze (and, consequently, most of the evidence offered in this section) pays the vast majority of attention to HIV/AIDS. Concerns about the security implications of disease in Africa tend to fall in one of thee categories: economic, political, and military. These three channels, according to the causal mechanisms of health security, could exacerbate economic deprivation, foster the breakdown of social institutions, and erode the legitimacy and authority of democratic political institutions and bureaucracies (Peterson and Shellman 2006: 6-8). From an economic perspective, the effects of disease have the potential to be dire. Nguyen and Stovel make the connection between disease and economics explicit. They write, “There is widespread agreement that HIV/AIDS causes or exacerbates economic vulnerability” (2004: 37). This is particularly problematic, as significant erosion in socioeconomic conditions in highly-afflicted states poses the leading threat to development in Africa (Nguyen and Stovel 2004: 35). Reports by the United Nations Development Program note that AIDS causes household incomes to decline by up to 80 percent. In addition, AIDS-afflicted households can see a 15 to 30 percent decline in food consumption (UNDP 2001). Another United Nations organization, the Food and Agricultural Organization, estimated in 2001 that AIDS killed 26 percent of the agricultural workforce in the ten most-afflicted sub-Saharan African states (International Crisis Group 2001). The education sector also faces severe effects from HIV/AIDS. Teachers form the foundation of the education system, and a well-functioning 18 education system is crucially important for political and economic development. Unfortunately, teachers appear to be particularly vulnerable to HIV infection. A 2001 report estimated HIV infection rates among teachers in southern Africa and found prevalence rates of 33 percent (South Africa), 40 percent (Zambia), 40 percent (Malawi), and 70 percent (Swaziland) (Peterson and Shellman 2006: 6). Politically, HIV/AIDS can introduce greater uncertain into the realm of governance. Butler notes that the HIV/AIDS epidemic could threaten to undermine the institutional and bureaucratic framework necessary for a functioning democracy. The loss of skilled civil service personnel and the basic organs of political competition could work against the tide of democratization that swept across sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s (Butler 2005: 5-7). A government’s failure to adequately address the epidemic could also weaken its legitimacy among the public (Butler 2005: 7), though recent public opinion analysis suggests that evaluations of a government’s AIDS policies are not significantly weakening support for governments in subSaharan Africa (Youde 2009). Strand et al. found that Zambia has experiences a significant increase in the number of parliamentary by-elections due to MP death since AIDS emerged in the country. Between 1990 and 2003, the years when Zambia’s AIDS prevalence rates were at their highest, the country held 38 such by-elections. By comparison, the country only had 14 byelections due to death between 1964 and 1984. More strikingly, the deaths between 1990 and 2003 were disproportionately among younger members. Fifteen of the 38 were between 40 and 49, while only 2 such deaths occurred among MPs over the age of 70 (Strand et al. 2006: 96-97). While not all of these deaths are due to AIDS, Strand et al. highlight that “70 percent of the MPs who died between 1990 and 2003 would have been in their most sexually active phase during parts of that time period” and hence at risk of contracting the virus (2006: 97). In 2000, 19 Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe announced that AIDS had killed at least three cabinet ministers and numerous traditional chiefs. Kenyan civil service officials declared that AIDS caused 86 percent of employee deaths in 1998 and 75 percent of police deaths between 1996 and 1998 (International Crisis Group 2001: 15-16). A 2003 report asserted that at least one-quarter of the South African police personnel were HIV-positive (Price-Smith 2003: 24). The military is of particular interest to discussion of security and particularly problematic for the spread of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. Most estimates suggest that infection rates among military members are at least twice as high as those for the general population. This translates into HIV infection rates of 40 to 60 percent (Elbe 2006: 121). More importantly, though, AIDS’ impact on the military could undermine military effectiveness and lead to the loss of experienced commanders, in turn undermining the military’s institutional role within the state and its ability to contribute to peacekeeping operations throughout the continent (Ostergard and Tubin 2004: 117). This could encourage non-state actors to take advantage of the state’s perceived weakness and challenge governments. Why would AIDS have such a detrimental impact on the military? AIDS, not war, is the leading cause of death among southern African militaries, accounting for over 50 percent of all in-service and post-service mortality (Heinecken 2009: 62). Reports suggest that between 40 and 80 percent of military members in the region are HIV-positive (Heinecken 2001: 121-122). Having such a large cohort of people with a fatal disease poses a massive challenge to any political institution. The challenge is particularly acute for the military for three reasons. One, it compromises military performance and effectiveness. If a large number of your people are sick, you cannot be as effective a force. It also decreases your opportunities to contribute to international security. The South African National Defense Force has had to curtail its 20 involvement in international peacekeeping and joint military exercises because they have not been able to field large enough contingents of HIV-free soldiers (Heinecken 2003: 291-292). Two, high rates of AIDS within society decreases the pool of potential recruits. There are fewer healthy people available to replace those already in the military who fall victim to AIDS. Finally, militaries suffer from a loss of leadership. The upper ranks of any military are crucially important for instilling a sense of discipline in new recruits and for ensuring operational effectiveness. As AIDS kills these people, the military not only loses their experience, but also faces a smaller pool of available replacements. Militaries face the prospect of protecting their nation’s security with less-experienced leaders (Ostergard 2002: 344). A shrinking recruiting cohort and diminished command efficacy could threaten the military’s ability to contribute positively to society and weaken its basic structure (Elbe and Ostergard 2007: 87). Being in the military also increases the risk of soldiers contracting AIDS. According to Singer, military members tend to be young men, away from home and their traditional social structures, with money to spend and a need to prove their manliness. As a result, soldiers often avail themselves of commercial sex workers, who are themselves at a heightened risk of being HIV-positive (Singer 2002: 148). After putting themselves at risk of infection, the soldiers often engage in sexual relations with the local population, perpetuating the virus’ spread (Elbe 2002: 163). Singer notes that peacekeepers deployed abroad are at such heightened risk for contracting HIV that the United Nations now mandates AIDS education as a required component of any peacekeeping mission it organizes (Singer 2002: 152). Again, the military’s ability to perform its duties and protect the state is weakened by AIDS. Some suggest that high rates of AIDS in the military increase the likelihood of hostilities. Soldiers who already face an early death from an infectious disease may be more prone to taking 21 risks, and states may be more willing to attack other states if they perceive them to be weakened by AIDS (Singer 2002: 148; Heinecken 2001: 123). A military weakened by high rates of illness and death due to AIDS may also be vulnerable to attack by regional competitors who see it as vulnerable and less able to mount an effective defense (International Crisis Group 2001: 21-22). More problematically, AIDS itself is becoming a weapon of war. HIV-positive soldiers have reportedly raped women and girls as they have retreated to cause a “slow genocide” (Elbe 2002: 153). By targeting civilians and deliberately attempting to spread AIDS, these soldiers aim to undermine the society and gradually make it collapse—at which time the departing soldiers can return and finish their original mission (Elbe 2002: 169-171). Not only does this further burden already weakened health systems in conflict zones and spread the disease to new areas, but it also serves to weaken the social fabric (Elbe 2002: 174)—which itself contributes to the disease’s spread within that country (Heinecken 2001: 126). This may change the power balance within the region and instill a mistrust of the military as an institution. Is security the right framework for promoting health in Africa? It is undeniable that Africa’s infectious disease burden places enormous strains on governments and societies throughout the continent. The losses associated with premature death dampen the abilities of governments throughout the continent to build stronger, more robust polities and economies Reducing the disease burden would increase gross domestic products throughout the continent, allow for the reallocation of government funds, and create an environment more hospitable to foreign investment. Infectious disease and health are undoubtedly important humanitarian issues for sub-Saharan Africa. The question arises, though, as to whether they are also security issues. 22 Writing on the securitization of HIV/AIDS, Elbe acknowledges that securitization brings with it certain dangers. It alters the nature of power, moving away from a sovereign, state-based conceptualization toward one that seeks to regulate populations and normalize behaviors according to impersonal norms. As a result, securitization redefines the social contract and creates ‘risk groups’ that may be the targets of stigmatization (Elbe 2009). Despite these dangers, though, he argues that the benefits of securitization outweigh the negatives. Securitizing AIDS has moved it up the political agenda and forced politicians to pay attention to a disease that they would otherwise ignore (Elbe 2009: 163-174). While it may be tempting to categorize infectious diseases in Africa as security issues or threats, it appears increasingly unlikely that such a strategy will be effective over the long term. The contentiousness over the meaning of health security and the nature of the health challenges faced by sub-Saharan African states suggest that human rights or humanitarianism may be more appropriate frameworks for promoting health and the development of a strong health care infrastructure throughout Africa. As evidenced above, there exists no clear consensus as to what health security means. Aldis outlines four different conceptions of the term. The first focuses on protection against threats coming from external sources. The second deals with new global health-related challenges that have emerged yet lack adequate responses. The third concentrates on the emergence and role of new actors in addressing health concerns, such as nongovernmental organizations and public-private partnerships. The fourth concerns how health has become linked with the foreign policy interests of a state (Aldis 2008: 371-372). This confusion poses a problem for African states, as it may lead to a cacophony of responses with no clear framework for 23 addressing concerns. Different actors operating from disparate understandings of health security throughout Africa could work at cross-purposes with each other. How could this happen? Four big concerns emerge for securitizing health within subSaharan Africa. First, a security framework focuses on a state protecting itself against threats rather than a broader, more holistic sense of global well-being. The irony in such a juxtaposition is that promoting global well-being and paying attention to the underlying determinants of health and disease would ultimately provide greater levels of protection. A security and threat posture frequently ignores the diseases and illnesses that cause the highest levels of mortality and privileges those diseases that most concern Western states. Diarrheal diseases rarely, if ever, are conceptualized as security threats, even though they are one of the most common killers in subSaharan Africa. Avian influenza, on the other hand, receives disproportionate attention, despite the fact that Africa as a whole has recorded only 83 cases (all but two of which were in Egypt) (World Health Organization 2009). Second, securitizing health narrows the range of diseases that receive attention and tends to focus on specific diseases themselves rather than the broader public health infrastructure. Most of the diseases that animate discussions of health security pose the greatest potential threat to Western states—SARS, avian influenza, swine flu. These diseases certainly have the potential to exact heavy costs on the international community, and taking precautionary measures to avoid negative consequences is certainly advised. However, focusing on these theoretical threats instead of the very real and already apparent infectious diseases threats facing sub-Saharan Africa distracts attention and finite resources. A focus on discrete diseases leads to stovepiping— creating programs and systems that address one illness or concern but do little to address broader measures of health. It is a focus on disease rather than a focus on health, yet health is more than 24 the absence of disease. Because measles, mosquito-borne diseases, and diarrheal diseases are largely absent from industrialized countries, they receive little if any attention from the security framework. The benefits Elbe associates with the securitization of AIDS have not translated to health more broadly, nor are they likely to do so. Thus, the illnesses with the greatest mortality and morbidity burdens in sub-Saharan Africa are largely left out. Third, despite efforts otherwise, the security framework still largely casts its analytical gaze at national, rather than human, security (McInnes 2008: 285). Policymakers and academics tend to think about security in terms of what could threaten the state. The language of security studies emphasizes direct threats—those that are readily apparent and provide a linear causal relationship to safety. It focuses on direct risks to state structures (particularly the military), potential epidemic diseases, and bioterrorism, though these are not the problems that dominate the African health agenda (McInnes and Lee 2006: 9). The nature of infectious disease, as described above, is better understood as an indirect, nonlinear threat. An infectious disease outbreak in and of itself is highly unlikely to bring a state to its knees or lead to armed conflict between two states. However, if state structures are already weakened or atrophied, and if a government lacks the governance capabilities to deal with an additional stressor, then it is possible that infectious disease could pose a serious risk to a state. It is this latter scenario that most challenges African states. If they are already weakened, then they may lack the reserve capacity and capability to handle an additional stressor. The outbreak of cholera in Zimbabwe is not in and of itself an existential threat to the Zimbabwean state; rather, it represents a stressor that could challenge the state’s ability to provide basic services. More importantly, though, Zimbabwe’s cholera outbreak poses a great burden on the people whose access to health services is already greatly compromised by the weakness of the state. A national security framework does 25 little for explaining why the international community should care about this outbreak, yet this is the mindset that still dominates most discussions on the nexus between health and security. Fourth and finally, the direct security effects envisioned by advocates of AIDS securitization (and health securitization more broadly) are largely speculative and overstated. While it is indeed true that high rates of infectious disease can have a deleterious effect on a state’s social, political, and economic institutions, there is little empirical evidence of direct military effects or civil conflict (Peterson and Shellman 2006). Barnett and Prins (2006) argue that much of the discussion about disease’s security effects rests on “factoids” and anecdotes that do not provide robust, reliable information. McInnes (2006) concurs, asserting that making blanket statements about the security implications of infectious disease across the entire African continent overstates and overgeneralizes the risk. Further, the statistical evidence for the relationship between poor health and internal instability remains ambiguous at best. The Central Intelligence Agency’s State Failure Task Force found that high infant mortality rates are a sign of poor quality of life, which is in turn a causal factor for internal instability. This finding suggests that infectious disease and poor health has an indirect effect on state security, not the direct effect commonly ascribed within the securitization literature (McInnes and Less 2006: 1617). These findings do not diminish the fact that poor health and infectious disease have severe effects on life within a state, nor do they suggest that infectious disease is not a problem with which African government need to grapple. They do suggest, though, that an argument that focuses on the direct security effects goes too far. By overstating the case, securitizers risk provoking a backlash when the hypothesized effects fail to materialize. Along these same lines, a security framework begs two important questions: security for whom and security from what? The health security discourse that has developed over the last 10 26 to 15 years has generally answered the first question by focusing on Western states. “Health security risks” or “new security risks” are those diseases that Western states fear could emerge from Africa and potentially come to their shores (McInnes and Less 2006: 11-12). It is not a discourse about health in general, nor is it even a discourse about helping Africa. It is instead a discourse that envisions Africa largely as an emitter of disease. What happens within African states with health concerns is irrelevant unless it could emerge and spread to industrialized states. This skews the international agenda, focusing attention away from those health issues that most directly affect African states and publics. The broader determinants of health, such as poverty and access to clean water and proper sanitation, receive short shrift. Packard reminds us that malaria eradication efforts failed not just because mosquitoes developed resistance to DDT and other insecticides. Instead, those efforts focused solely on the transmission vectors without examining the underlying social and economic conditions that put people at risk of contracting the disease in the first place (Packard 2007). Africa itself receives short shrift, too. Africa is not important in this construction because of the suffering from infectious disease or the disproportionate child mortality burden it experiences; it is only important insofar as it could potentially be the source of diseases that could threaten wealthy industrialized states. Africa is more of a signifier than a participant in the larger conversation about international health policy. If the above is true and the security framework has largely come to dominate the discussion of African health, why is this the case? McInnes and Lee, while approving of the increased attention health has received within the international agenda, highlight “the apparently successful attempt to move health beyond the social policy and development agenda, into the realms of foreign and security policy” (2006: 6). One answer might be “forum-shifting.” Health 27 is, in many ways, a cross-cutting issue that could potentially fit within a number of different policy arenas. By shifting health away from the realms of social and development policy and toward foreign and security policy, advocates seek to operate within the diplomatic arenas which are likely to bring them more attention, more resources, and more favorable outcomes (Fidler 2009: 29). Security, for better or worse, commands far more attention and far more resources than social policy or international development. Policymakers may attention to security issues, particularly security threats. Security threats grab public and political attention in a way that development policy fails to do. A security discourse may get policymakers to focus on Africa in a way that they may otherwise be unlikely to do. While this strategy may have led Western states to pay more attention to Africa and health issues, it does not appear to be a useful long-term strategy. Aldis documents a growing suspicion of health securitization. Developing state governments are increasingly uncomfortable with the framework because of the associated loss of control and policy autonomy. Since the health security discourse largely focuses on those diseases that could threaten developed states, developing states like those in Africa find their health policies increasingly dominated by responding to developed state concerns. This leads to the creation of more stovepiped programs that have too little overlap to address the majority of health concerns. It also undermines state sovereignty and autonomy, as health programs in African states become increasingly dependent upon donor requests and conditionalities (Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2005: 8). As a result, governments in sub-Saharan Africa are increasingly reluctant to accept the categorization of health as a security concern (Aldis 2008: 372-373). Furthermore, conceptualizing health as a security issue frequently leads to a crisisoriented mentality. New and novel diseases receive disproportionate attention, and attention 28 focuses on epidemic diseases that threaten to spread beyond borders (Fidler 2009: 29). Endemic diseases, which are responsible for the majority of Africa’s disease mortality and morbidity burden, receive less attention because they are assumed to be part of the fabric of the country. A short-term crisis mentality may lead to rapid, immediate responses, but addressing the underlying determinants of health requires long-term, sustained commitments. A crisis-based response emphasizes defensive measures, but pays less attention to long-term processes like prevention, strengthening the public health infrastructure, and building surveillance capabilities in developing countries (Feldbaum 2009: 2). While praising the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), Patterson notes that its relatively quick passage demonstrated a belief among policymakers that AIDS was less a long-term development issue and more of a short-term fix. “Emergencies require quick attention, but the implication is that an emergency can be fixed relatively rapidly” (Patterson 2006: 139). Fixing a country’s health care infrastructure or ensuring that children have access to lifesaving vaccinations will not emerge from a crisis mentality. That sort of sustained attention will likely only emerge from a framework that recognizes the value of addressing health concerns in Africa as human rights or humanitarian issues. As Feldbaum notes, “Addressing most global health issues cannot be justified by national security considerations…some serious global health issues will likely never be linked credibly to US national security interests. Such issues will have to rely on moral, humanitarian, or other frameworks to win US funding and political support” (2009: 8). Instead of focusing on security-based concerns, foreign governments that want to promote improved health in Africa should base their assistance and commitment on values of generosity, compassion, sharing, and creating the necessary preconditions for economic 29 development and global prosperity (Committee on the US Commitment to Global Health 2008: 7). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, attempting to create a direct, linear relationship between health and security may actually work against its advocates’ desires. Barnett and Dutta find no conclusive evidence for a direct link between HIV prevalence and state fragility (2008: 17), while Sato (2008) uncovers no statistically significant relationship between AIDS and state fragility among low-income countries under stress. Peterson describes the paradox thusly: By overdrawing the link between infectious disease and security, however, public health and human security advocates sabotage their own attempts to motivate developed nations to fights AIDS in Africa and elsewhere…Linking an urgent issue to security may raise awareness, but it likely will also hinder much of the cooperation that human security and public health advocates seek and that the disastrous humanitarian and development effects of infectious diseases demand (2007: 38). Addressing health in Africa requires international cooperation and a willingness to share among states. Security encourages governments to think narrowly about their own interests and how they can gain or preserve their advantages over others. Humanitarian health objectives are largely at odds with this state-centric model of security because the former offers a far more inclusive vision and responsibility than the latter (Feldbaum et al. 2006: 196). Nattrass, one of the leading experts on AIDS and its impact on societies, echoes some of these same themes. She sees a link between the disease and economic security, but challenges the notion that it is linked to state security (Nattrass 2003: 2). AIDS undermines democracy because it undermines the economic foundations of a society, and she acknowledges that this could in 30 turn have an indirect impact on global security, but she asserts that this connection is too far removed and overlooks the very real and direct connections between AIDS and economics (Nattrass 2003: 8-9). These connections, she argues, are the ones that will impact the most people in the most direct manner. Instead of calling AIDS a security threat, Nattrass wants to keep attention on economic and humanitarian issues. She sees little benefit in calling AIDS orphans a threat to state security as Singer does (Singer 2002: 151), saying that this obscures the humanitarian dimensions of children losing their parents prematurely and being forced to take jobs and raise their siblings. The language of security distracts the international community from AIDS’ far more direct impacts. Advocates of human security argue that including economics, food, the environment, and freedom from violence makes sense because these are the threats most people face in their day-to-day life. Nattrass largely agrees, but does not see why we need to call these threats a security issue. Suggestions and conclusions In this paper, I have argued that security is not the most appropriate framework for encouraging national and international action on infectious disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Infectious diseases cause a disproportionate share of the region’s morbidity and mortality, and the international community clearly has an interest in reducing the spread of AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, diarrheal diseases, and lower respiratory infections. Calling these diseases security threats or issues, while potentially attention-grabbing, distracts attention from the nature of the threat posed by these diseases and skews funding. If security is inappropriate, what is a better framework for encouraging action and attention? I propose conceptualizing infectious disease as a human rights or development issue 31 instead of a security issue. Such a framework would emphasize the connections between human rights as written in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights, among others, and good health. People need to be healthy in order to take advantage of and realize their inherent human rights, and numerous human rights charters explicitly recognize a right to health. Some, like the African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights and the South African Bill of Rights, go even further and specify a positive obligation for the government to ensure the good health of their citizenry. Using a human rights or development framework for addressing infectious disease in Africa instead of security has four distinct advantages. First, it emphasizes the long-term nature of these issues. Neither human rights nor development can be realized in a few short years. They are an ongoing project, requiring constant attention and vigilance. Doing so requires the active attention of both local governments and the international community in a collaborative manner. Second, this framework encourages paying attention to a wider range of infectious diseases and health threats in sub-Saharan Africa. Some of the leading causes of death in the region, like malaria, lower respiratory infections, and diarrheal diseases, overwhelmingly affect children. As such, they are highly unlikely to receive attention within a security framework. Few would argue that the deaths of children under the age of five is likely to destabilize a country, provoke international aggression, or lead to the collapse of a national government. The security framework encourages this selective attention, emphasizing those diseases that may have military implications rather than those that have the greatest effects on the population as a whole. This has helped to distort health spending, with AIDS receiving a disproportionate share of health-related aid from international sources (Shiffman 2007). A human rights or development 32 framework pays attention to a wider range of infectious diseases because it has a more holistic approach. Children may not militarily relevant, but their survival and prosperity can lead to greater economic prosperity and political development over time. Third, a human rights or development framework resonates with developing narratives, Over the past 20 years, AIDS activists have come to situate their claims for treatment and prevention programs in human rights terms (Youde 2008b). Universal access to antiretroviral drugs has gained currency as an international norm, altering existing paradigms about pharmaceutical access and health care expenditures (Youde 2008a). Tapping into this emerging consensus will allow for greater long-term success. Finally, a human rights framework allows for greater participation from non-state actors. Security is widely seen as the sole domain of the state. Given the challenges ill health poses to sub-Saharan Africa, though, it is highly unlikely that state governments on their own can adequately address them. A human rights and development framework, on the other hand, recognizes the value of reaching out to and incorporating voices from nongovernmental organizations, philanthropic organizations, and private business. Incorporating all of these difference groups along with governments and finding mechanisms for coordination heightens the chance that important concerns will be addresses and less prominent diseases will not be neglected. Calling health in sub-Saharan Africa may initially appear attractive, and its discourse has been dominant in recent years. However, its shortcomings limit its efficacy. The infectious disease threat in sub-Saharan Africa is real and significant, but a security framework has not and will not produce the sort of long-term attention necessary to adequately address the issue. 33 WORKS CITED Aitsi-Selmi, A. 2008. “Harben Lecture: World Poverty and Population Health: The Need for Sustainable Change.” Public Health 122: 597-601. Aldis, William. 2008. “Health security as a public health concept: a critical analysis.” Health Policy and Planning 23: 369-375. Amor, Yanis Ben, Bennett Nemser, Angad Singh, Alyssa Sankin, and Neil Schluger. 2008. “Underreported Threat of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Africa.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 14: 1345-1352. Aradau, Claudia. 2004. “Security and the Democratic Scene: Desecuritization and Emancipation.” Journal of International Relations and Development 4: 388-413. Aradau, Claudia. 2006. “Limits of Security, Limits of Politics? A Response.” Journal of International Relations and Development 9: 81-90. Ashburn, Kim, Nandini Oomman, Dave Wendt, and Steve Rosenzweig. 2009. Moving Beyond Gender as Usual. Washington: Center for Global Development. AVERT. 2009a. “HIV and AIDS in Africa.” http://www.avert.org/aafrica.htm (accessed 29 July 2009). AVERT. 2009b. “HIV, AIDS, and Children.” http://www.avert.org/children.htm (accessed 29 July 2009). Balzacq, Thierry. 2005. “The Three Faces of Securitization: Political Agency, Audience, and Context.” European Journal of International Relations 11: 171-201. Barnett, Tony and Indranil Dutta. 2008. HIV and State Failure: Is HIV a Security Risk? ASCI Research Report No. 7 (April). New York: SSRC. Barnett, Tony and Gwyn Prins. 2006. “HIV/AIDS and Security: Fact, Fiction, and Evidence—A Report to UNAIDS.” International Affairs 82: 359-368. Boschi-Pinto, Cynthia, Claudio F. Lanata, Walter Mendoza, and Demissie Habtee. “Diarrheal Diseases.” In Dean T. Jamison, Richard G. Feachem, Malegapuru W. Makgoba, Eduard R. Bos, Florence K. Baingana, Karen J. Hoffmann, and Khama O. Rogo (Eds.) Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa (2nd Edition). Washington: World Bank. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=dmssa&part=A527 (accessed 25 August 2009). Burkle, Fredrick. 2009. Personal communication with author. 30 June. 34 Butler, Anthony C. 2005. “The Negative and Positive Impacts of HIV/AIDS on Democracy in South Africa.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 23: 3-26. Buzan, Barry, Ole Waever, and Japp de Wilde. 1998. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder: Lynne Reinner. c.a.s.e. collective. 2006. “Critical Approaches to Security in Europe: A Networked Manifesto.” Security Dialogue 37: 443-487. Chaisson, Richard E. and Neil A. Martinson. 2008. “Tuberculosis in Africa—Combating an HIV-Driven Crisis.” New England Journal of Medicine 358: 1089-1092. CIA. 2009. “CIA World Factbook—Swaziland.” https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/theworld-factbook/geos/wz.html (accessed 29 July 2009). Committee on the US Commitment to Global Health. 2008. The US Commitment to Global Health: Recommendations for the New Administration. Washington: National Academies Press. Crosby, Alfred W. 1986. Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 9001900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Crosby, Alfred W. 2003. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Deudney, Daniel. 1990. “The Case against Linking Environmental Degradation and National Security,” Millennium 19: 461-476. Eagle, William. 2009. “NGOs Urge Renewed Fight Against Diarrheal Diseases.” Voice of America (19 June). http://www.voanews.com/english/archive/2009-06/2009-06-19voa36.cfm?CFID=269568441&CFTOKEN=22470735&jsessionid=6630483257cd6f979e 6b26576c7f221260b2 (accessed 29 July 2009). Elbe, Stefan. 2002. “HIV/AIDS and the Changing Landscape of War in Africa.” International Security 27: 159-177. Elbe, Stefan. 2006. “Should HIV/AIDS Be Securitized? The Ethical Dilemmas of Linking HIV/AIDS and Security.” International Studies Quarterly 50: 119-144. Elbe, Stefan. 2009. Virus Alert: Security, Governmentality, and the AIDS Pandemic. New York: Columbia University Press. Elbe, Stefan and Robert L. Ostergard, Jr. 2007. “HIV/AIDS, the Military, and the Changing Landscape of Africa’s Security.” In HIV/AIDS and the Threat to National and International Security, Robert L. Ostergard, Jr., ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 35 Feldbaum, Harley, Preeti Patel, Egbert Sondorp, and Kelley Lee. 2006. “Global Health and National Security: The Need for Critical Engagement.” Medicine, Conflict, and Survival 22: 192-198. Feldbaum, Harley. 2009. US Global Health and National Security Policy. Washington: CSIS. http://www.csis.org/files/media/csis/pubs/090420_feldbaum_usglobalhealth.pdf. Accessed 5 July 2009. Fidler, David P. 2009. “Vital Signs.” The World Today (February): 27-29. Gallup, John Luke and Jeffrey Sachs. 2001. “The Economic Burden of Malaria.” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 64: 85-96. Heinecken, Lindy. 2001. “HIV/AIDS, the Military, and the Impact on National and International Security.” Society in Transition 32: 120-127. Heinecken, Lindy. 2003. “Facing a Merciless Enemy: HIV/AIDS and the South African Armed Forces.” Armed Forces and Society 29: 281-300. Heinecken, Lindy. 2009. “The Potential Impact of HIV/AIDS on the South African Armed Forces: Some Evidence from Outside and Within.” African Security Review 18: 60-77. Huysmans, Jeff. 1998. “Revisiting Copenhagen: Or, on the Creative Development of a Security Studies Agenda in Europe.” European Journal of International Relations 4: 479-505. Kolodziej, Edward W. 1992. “Renaissance in Security Studies? Caveat Lector!” International Studies Quarterly 36: 421-438. Lim, Yee-Wei, Marc Steinhoff, Federico Girosi, Douglas Holtzman, Harry Campbell, Rob Boer, Robert Black, and Kim Mulholland. 2006. “Reducing the Global Burden of Acute Lower Respiratory Infections in Children: the Contribution of New Diagnostics.” Nature 5442: 9-16. Liotta, P.H. 2005. “Through the Looking Glass: Creeping Vulnerabilities and the Reordering of Security.” Security Dialogue 36: 49-70 MacFarlane, S. Neil and Yuen Foong Khong, 2006. Human Security and the UN: A Critical History. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press). McInnes, Colin. 2006 “HIV/AIDS and Security.” International Affairs 82: 315-326. McInnes, Colin. 2008. “Health.” In Security Studies: An Introduction, Paul Williams, Ed. New York: Routledge. McInnes, Colin and Kelley Lee. 2006. “Health, Security, and Foreign Policy.” Review of International Studies 32: 5-23. 36 McNeill, William H. 1977. Plagues and Peoples. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books. Nattrass, Nicoli. 2003. “AIDS and Human Security in Southern Africa.” Social Dynamics 28: 119. Nchinda, Thomas. 1998. “Malaria: A Reemerging Disease in Africa.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 4: 398-403. Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2005. HIV/AIDS, Security, and Democracy: Seminar Report. 4 May. Clingendael Institute, The Hague, The Netherlands. http://asci.ssrc.org/doclibrary/seminar_report.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2009. Nguyen, Vinh-Kim and Katherine Stovel. 2004. The Social Science of HIV/AIDS: A Critical Review and Priorities for Action. SSRC Working Group on AIDS. New York: SSRC. Ostergard, Robert L., Jr. 2002. “Politics in the Hot Zone: AIDS and National Security in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 23: 333-350. Ostergard, Robert L., Jr. and Matthew R. Tubin. 2004. “Between State Security and State Collapse: HIV/AIDS and South Africa’s National Security.” in The Political Economy of AIDS in Africa, eds. Nana K. Poku and Alan Whiteside. Aldershot: Ashgate. Packard, Randall M. 2007. The Making of a Tropical Disease: A Short History of Malaria. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Paris, Roland. “Human Security: Paradigm Shift or Hot Air?” International Security 26 (2001): 87-102 Peterson, Susan. 2007. “Human Security, National Security, and Epidemic Disease.” In HIV/AIDS and the Threat to National and International Security, Robert L. Ostergard, Ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Peterson, Susan and Stephen Shellman. 2006. “AIDS and Violent Conflict: The Indirect Effects of Disease on National Security.” Institute for the Theory and Practice of International Relations Working Paper. http://www.wm.edu/irtheoryandpractice/security/papers/AIDS.pdf (accessed 10 September 2009). Population and Development Review, “Economic and Demographic Trends and International Security: a US Analysis.” Vol. 15 (1989): 587-599 Price-Smith, Andrew T. 2009. Contagion and Chaos: Disease, Ecology, and National Security in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge: MIT Press. 37 Sato, Azusa. 2008. Is HIV/AIDS a Threat to Security in Fragile States? ASCI Research Report No. 10 (April). New York: SSRC. Singer, P.W. 2002. “AIDS and International Security.” Survival 44: 145-158. Singh, Jerome Amir, Ross Upshur, and Nesri Padayatchi. 2007. “XDR-TB in South Africa: No Time for Denial or Complacency.” PLoS Medicine 4: 19-25. Strand, Per, Khabele Matlosa, Ann Strode, and Kondwani Chirambo. 2006. HIV/AIDS and Democratic Governance in South Africa: Illustrating the Impact on Electoral Processes. Pretoria: IDASA. Taureck, Rita. 2006. “Securitization Theory and Securitization Studies.” Journal of International Relations and Development 9: 53-61. Thucydides. 1980. History of the Peloponnesian War. New York: Penguin. UNAIDS. 2007. Sub-Saharan Africa AIDS Epidemic Update Regional Summary. Geneva: UNAIDS. UNAIDS. 2008. 2008 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS. United Nations Development Program. 1994. Human Development Report, 1994. New York: Oxford. United Nations Development Program. 2001. “HIV/AIDS Implications for Poverty Reduction.” UNDP Policy Paper. Background Paper prepared for the United Nations Development Program for the UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS. Waever, Ole. 1995. “Securitization and Desecuritization.” In On Security, Ronnie Lipschutz (Ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. Waever, Ole. 2000. “The EU as a Security Actor: Reflections from a Pessimistic Constructivist on Post Sovereign Security Orders.” In International Relations Theory and the Politics of European Integration, Morten Kelstrup and Michael C. Williams (Eds.). London: Routledge. Walt, Stephen. 1991. “The Renaissance of Security Studies.” International Studies Quarterly 35: 211-239. World Health Organization. 2002. “Facts About Health in the African Region of the WHO.” http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs314/en/index.html (accessed 29 July 2009). World Health Organization. 2004. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization. 38 World Health Organization. 2007. The World Health Report 2007: A Safer Future: Global Public Health Security in the 21st Century. Geneva: World Health Organization. World Health Organization 2007b. “Tuberculosis.” http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/index.html (accessed 30 July 2009). World Health Organization. 2009. “Cumulative Number of Confirmed Cases of Influenza A/(H5N1) Reported to WHO.” 1 July. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/cases_table_2009_07_01/en/inde x.html. Accessed 17 July 2009. World Health Organization. 2009b. “Malaria.” http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/index.html (accessed 30 July 2009). Youde, Jeremy. 2008a. “From Resistance to Receptivity: Transforming the AIDS Crisis into a Human Rights Issue.” In The International Struggle for New Human Rights, Clifford Bob, ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Youde, Jeremy. 2008b. “Is Universal Access to Antiretroviral Drugs an Emerging International Norm?” Journal of International Relations and Development 11: 415-440. Youde, Jeremy. 2009 (Forthcoming). “Government AIDS Policies and Public Opinion in Africa.” Politikon. Zinsser, Hans. 1934. Rats, Lice, and History. Boston: Little, Brown. 39 Table 1. Leading Causes of DALYs in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2004. Disease DALYs (millions) Percent of total DALYs HIV/AIDS 46.7 12.4 Lower respiratory infections 42.2 11.2 Diahhreal diseases 32.2 8.6 Malaria 30.9 8.2 Neonatal infections 13.4 3.6 Birth asphyxia/trauma 13.4 3.6 Prematurity/low birth weight 11.3 3.0 Tuberculosis 10.8 2.9 Traffic accidents 7.2 1.9 Protein-energy malnutrition 7.1 1.9 Source: World Health Organization 2004: 45 40 Table 2. Leading Causes of Death in Sub-Saharan Africa by Age, 2002. 0-4 years 5-14 years 15-29 years All Ages infections HIV/AIDS HIV/AIDS infections HIV/AIDS Tuberculosis Malaria Diarrheal Traffic diseases accidents Violence infections Perinatal Measles Lower respiratory Diarrheal infections diseases Traffic Perinatal accidents conditions Lower respiratory Malaria Lower respiratory conditions Trypanosomiasis HIV/AIDS Source: World Health Organization 2002 Lower respiratory

![Africa on the rise - Health[e]Foundation](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005761249_1-4e2609b64b2c374f99ff6e9dbe45edb8-300x300.png)