It`s Not Easy Being Green

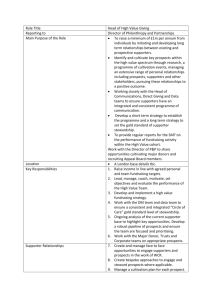

advertisement