Can research information reduce biased perceptions of media

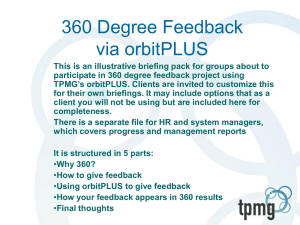

advertisement

Can research information reduce biased perceptions of media? The case of hostile media and third person perceptions Yariv Tsfati, Senior Lecturer Hannah Huino, MA Candidate Department of Communication, University of Haifa Address correspondence to: Yariv Tsfati, Department of Communication, University of Haifa, 31905 ISRAEL, ytsfati@com.haifa.ac.il , Fax: ++972-48249120, Tel: ++972-48240012 Paper submitted to the 64th Annual Conference of the World Association for Public Opinion Research Can research information reduce biased perceptions of media? The case of hostile media and third person perceptions The hostile media perception (HMP) takes place when partisans of opposing sides of a social conflict judge seemingly neutral news coverage of the conflict as biased against their point of view (Vallone et al., 1985). The third person perception (TPP) refers to the human tendency to perceive larger media effects on others as compared to self (Davison, 1983). Both perceptions are considered in the communication and public opinion literature as perceptual biases (e.g., Perloff, 1989). Under certain scenarios, both perceptions may lead to problematic social consequences such as mistrust in democracy (Tsfati & Cohen, 2005a), minority alienation (Tsfati, 2007), and even support of violent protest (Tsfati & Cohen, 2005b). This happens especially when members of political minorities that hold extreme political views think that media are biased and powerful. Correcting biased perceptions of media is thus a challenge for media scholars. This paper asks a simple question: Does merely informing people about the research literature regarding biased perceptions of media attenuate such biases? Could it be that telling people that research shows that people are biased in their perceptions of media bias and media impact will reduce biased media perceptions? Social psychological research demonstrates that it is possible to attenuate and even cancel perceptual biases by educating experimental participants regarding biased unconscious processing (Pronin & Kugler, 2007, Study 5). Therefore, the current investigation explores whether similar processes take place when it comes to the HMP and TPP. The hostile media perception and the third person effect. In a seminal study, Vallone et al. (1985) showed several news segments about the 1982 Beirut massacre to Pro-Arab, Pro-Israel and neutral students on the Stanford campus. Participants were then requested to evaluate the coverage. As expected, each group saw the coverage as less sympathetic to their side, more sympathetic to the opposing side and generally hostile to their point of view. This pattern of findings has been dubbed the Hostile Media Phenomenon (HMP). The HMP finding was not only replicated in a diversity of contexts (Cohen & Tsfati, in press, for a recent review), subsequent results documented the potential effects of HMPs on the political and social alienation of the audience, and other outcomes (Tsfati 2007). Other findings demonstrate that HMPs reduce audience trust in media (Tsfati & Cohen, 2005a). Research also demonstrates that hostile media perceptions affect audience estimations of public opinion. According to this line of research, dubbed “the persuasive press inference,” people perceive that slants in present media coverage will have an impact on future public opinion. Thus, hostile media perceptions contribute to perceptions of a hostile climate of opinion (Gunther, 1998; Gunther & Christen, 2002). Similarly to the HMP, the Third Person Perception (TPP) is also a well documented perceptual bias. This line of research that has started with W. Phillip Davison’s landmark study (1985) is now one of the most popular contemporary theories in media research (Bryant & Miron, 2004). Meta analyses document a highly robust statistical difference between people’s perceptions of media effects on self and others (Paul, Salwen, & Dupagne, 2000; Sun, Pan & Shen, 2008). As in the case of HMPs, TPPs were found to be consequential perceptions. Most notably, research has documented that TPPs are associated with audience support of message restrictions: When people perceive large effects of harmful messages on others compared to self, they tend to espouse censorship (Salwen 1998; see Xu and Gonzebach 2008 for a meta-analysis). In addition to these “restrictive” reactions, scholars have proposed that some of the reactions to perceptions of media impact are “corrective.” Rojas (2010) demonstrated that citizens perceiving strong influences of biased media may take political actions such as trying to persuade a friend to vote for a specific candidate, or expressing their views offline (by attending rallies or protests, or signing petitions) or online (by posting their views in online forums) in order to compensate for the perceived effects of media and counteract their biased message “that would otherwise sway public opinion” (p. 343). Similar corrective actions were documented in additional contexts (Chia, 2006; Huh & Langteau, 2007; Golan, Banning and Lundy, 2008; Tsfati & Cohen, 2005b; Tsfati, Ribak & Cohen, 2005). Experimental research has established that perceptions of media impact are the cause of behavioral intentions (Dillard, Shen & Vail, 2007; Tal-Or et al., 2010). The TPP and the HMP are similar in several respects. Both are well-documented, robust and potentially highly consequential perceptual biases, receiving considerable attention in recent years. Both HMPs and TPPS stem from motivational self-enhancement as well as cognitive factors. Interestingly, the effects of perceptions of media influence are amplified when they are coupled with perceptions of media hostility (Rojas 2010). Finally, both perceptions are also empirically related. Statistically significant relationship between HMPs and TPPs has long been established (Vallone et al., 1985; Perloff, 1989), with more recent findings demonstrating that the associations hold even when controlling for demographic and political variables (e.g, Tsfati & Cohen, 2005a). That is, the more people think media are hostile to their point of view, the more they perceive that media exert a strong influence on others compared to them. Given the similarities and empirical associations between HMPs and TPPs the current investigation examines both perceptions of media. Given their potentially detrimental effects on democratic life, finding a way to correct both biased perceptions of media (HMPs focusing on media hostility and TPPs on media impact) is an endeavor worthwhile taking. Correcting biased perceptions by providing information Research in social psychology demonstrates that educating participants regarding the research literature about biases and their unconscious nature results in attenuating biased perceptions. This was found in the context of “the bias blind spot” which is the tendency of individuals to perceive that others are relatively more biased, compared to themselves. Pronin and Kugler (2007) argued that this “bias blind spot” may be explained by the fact that people rely on introspective evidence when assessing bias in self, but on behavioral evidence when assessing bias in others. The purpose of their Study 5 manipulation was to educate participants about the limits of introspection. Their experimental participants, students at Princeton University, read a putative article from Science reviewing social psychological phenomena that operate unconsciously, while their control participants read an article about a technique for assessing change in environmental pollution. Then, in a supposedly unrelated study, all participants were requested to rate their own susceptibility to a variety of psychological biases, relative to other students. While participants in the control condition demonstrated a bias blind spot by reporting that they are less susceptible to bias than others, participants in the experimental condition did not exhibit such a bias. The blind spot bias is similar in many respects to the TPP. Both require a comparison between self and others and both could be seen as special cases of the better than average bias. If information about research on the limits of human introspection and resulting biases attenuated the bias blind spot then perhaps information about research on a specific biased perception such as the TPP would attenuate that same biased perception. Similarly to what supposedly happened in the Pronin and Kugler (2007) study, reading the manipulation should reduce confidence in the introspective data used when one assesses media impact on self, increase awareness of the possibility of bias and thus attenuate biased processing. Thus, it is possible to suggest that: (H1) Exposure to information on research on the TPP would reduce the TPP A similar process may operate in response to reading information about the HMP. Reading information about this research literature may activate the possibility of biased processing in the minds of participants and hence reduce expression of negative perceptions towards the news coverage: Simply, in light of the information on biased processing, displaying HMPs may reflect negatively on the perceiver, as someone who is himself biased. Thus, confidence in the introspection-based assessments, such as those offered by the different standards explanation of the HMP (Giner-Sorolla & Chaiken, 1994; Gunther & Liebhart, 2007), may grow weaker, resulting with attenuated HMPs. In other words, the research information on the HMP may weaken the tendency to view opposing arguments as less legitimate and consequently their presentation in news reports should not be seen as proof of biased reporting. Thus, it is possible to hypothesize that (H2) Exposure to information on research on the HMP would reduce the HMP In sum, the approach taken in the experiment that follows is similar, though far from being identical to the approach used in the Pronin and Kugler (2007) study. Like Pronin and Kugler (2007), we provide experimental participants with evidence from the research literature. Unlike Pronin and Kugler (2007), our experimental manipulations educate participants regarding a specific bias rather than about an array of human weaknesses. Specifically, we provide them to information about communication research about biased perceptions of media, similarly to what is done in academic programs in communication, and examine whether this information reduces their subsequent HMPs and TPPs. The context: Israeli policies in East Jerusalem While the Western part of Jerusalem was under Israeli control since it proclaimed independence in 1948, the Eastern part of the city was annexed to Israel after it was conquered in 1967 from Jordan. The municipal borders of the city were expanded after the 1967 war to include the eastern city and adjoining territories that were for the most part used to build neighborhoods for Jew, which Palestinians see as illegal Israeli settlements in the heart of the capital of their future Palestinisan capital. Scholars have termed the Israeli policy in Jerusalem “physical annexation through construction” (Klein, 2008), and this policy changed the demographic reality in the city: About half of Jerusalem’s Jewish population now reside on formerly Jordanian lands, and the number of Jews now living in East Jerusalem is almost equal to the number of Palestinians. At the same time that Israel has moved to expand Jewish presence in East Jerusalem, government policies have made the lives of Palestinians there extremely difficult: Large construction projects for Arabs were not initiated, the permanent residence status of a growing number of Palestinians was questioned, and since the 1990s the government started supporting Jewish settler non-profit organizations that bought homes in Palestinian neighborhoods with the intent of settling Jews there in order to shatter the ethnic homogeneity of these neighborhoods. In addition to these steps, Israel has shut down Palestinian governing institutions in Eastern Jerusalem, built a separation wall disrupting the connection between the Palestinian metropolitan center in East Jerusalem and Palestinian suburbs and cities in other parts of the West Bank, and has used measures such as land confiscations and house demolitions to strengthen Jewish control in the Eastern city. In 2010, the issue of Jewish construction in East Jerusalem has caused tensions between the right wing government in Israel (led by Benjamin Netanyahu) and the Obama administration. Israeli news media reported that Israel was slowing down the initiation of new construction projects for Jews in East Jerusalem, in order to avoid American pressures. This has raised criticisms from the right wing, whose supporters advocate that any compromise on Jewish construction in the city would lead to a compromise on Israeli sovereignty. The right wing deny any Palestinian claims for control in East Jerusalem, citing biblical promises and religious and security reasons for continuing Israeli dominance in the Eastern city. Right wing supporters advocating the continuation of construction for Jews in Eastern Jerusalem also cite reasons such as housing shortage amidst rising real estate prices and a large natural forest park, preventing the expansion of the city to the west. While, traditionally, there has been a consensus in Israeli public opinion regarding the unity of the city under Israeli sovereignty under any possible peace deal, larger segments of the Israeli left are increasingly supportive of initiatives (such as the 2000 Clinton Parameters and the 2003 Geneva initiative) that include the division of the city along ethnic lines. In recent years, several left wing movements started protesting against Israeli urban planning and construction policies in East Jerusalem that they view as infringing Palestinian rights, and hurting the chances of a peace deal between Israel and the Palestinians. In 2010, left wing activists held weekly demonstrations in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood protesting what they view as rightwing legal takeover of Palestinian houses and the initiation of a housing project for Jews in the neighborhood, and more generally the inequality in Urban planning in Jerusalem. The context of the conflict in Jerusalem is suitable for research on HMPs and TPPs, as one can locate two distinguishable opposing political groups, whose members are emotionally involved in the topic at hand. In this context, Israeli right wing supporters are expected to perceive news coverage regarding the situation in East Jerusalem as extremely supportive of the Palestinian and left-wing view regarding Jerusalem, whereas left wing supporters are expected to perceive the coverage as supportive of expanding Jewish settlements and presence there. According to the TPP hypotheses, both groups are expected to perceive that the coverage would have larger impact on others. In the following pages, we examine whether educating participants regarding the TPP and HMP reduces these perceptions. Methods The hypotheses were investigated using a simple between-subjects experimental design. To conform to the standard design of an HMP study, politically involved respondents belonging to opposing sides of the Jerusalem issue were recruited (n=213). The sample was composed of antisettlements (left-winged) and pro-settlements (right-winged) politically-involved respondents recruited either in residential areas with a strikingly high proportion of votes for ideologically extreme right-wing or left-wing Israeli parties (left-wing Kibbutzim or right-wing settlements) or recruited when participating in political events (demonstrations or political meetings) of these ideological groups. As expected right wing respondents were strongly opposed to imposing a freeze on construction for Jews in East Jerusalem (M = -3.93, SD = 2.34, on -5 = “strongly opposed” to +5 = “strongly in favor” scale). Right wing respondents were also strongly opposed to plans (such as the Clinton plan) that include dividing the city so that Jewish neighborhoods will remain in Israeli sovereignty and Palestinian neighborhoods will be transferred to Palestinian control, with special arrangements to the holy places (M = -3.82, SD = 2.58 on a similar scale). Left wing respondents were strongly in favor of both imposing a freeze on construction (M = +3.41, SD = 2.56) and political plans that include compromises in Jerusalem (M = +3.56, SD = 2.18). The differences between right and left respondents on these items were statistically significant (t (202) = 21.18, p < .001 for construction freeze; t (202) = 21.97, p < .001 for support of plans that include compromise). Participants were randomly assigned to three experimental groups: Participants in the “information-HMP” group read a paragraph describing academic research on the HMP. Participants in the “information-TPP” condition read a paragraph describing scholarly research on the TPP. Participants in the control condition received no information and proceeded directly to the next stage of the questionnaire. In the next stage, all respondents read a short news story about the situation in East Jerusalem. Subsequently, respondents were asked to evaluate bias in the news story and a set of questions about their perceptions of its impact. The questionnaire also included several demographic and political questions that would serve as covariates. Lastly, participants were debriefed and thanked. Stimulus materials Educational manipulations. Participants in the HMP-information manipulation read a short article (237 words) titled “the hostile media phenomenon in communication research”. The subheading was “a review based on research articles published in leading communication journals”. The article described the Vallone et al (1985) study and findings, mentioned that the findings were replicated in a diversity of contexts and cultures, and explained that researchers deduce that the biases stem from readers and viewers and not from the news coverage. Finally, the short article claimed that the hostile media perception takes place as part of an unconscious psychological process and in fact respondents from the two opposing sides in the conflict are not aware of their bias. Participants in the TPP-information manipulation read a similar short article (296 words) about the TPP. To keep the article as similar as possible to the HMP condition it also referenced a 1985 Stanford University 1985 that found that respondents felt that coverage of the 1982 would have large impact on others compared to self (in fact the Vallone et al, 1985 did contain results demonstrating large perceptions of media impact on neutral audiences). The article likewise cited the Davison study and claimed that TPP findings were replicated in a diversity of contexts and cultures. It was stressed that scholars maintain that the biases stem from readers and viewers and not from the news coverage itself. Finally, the short article claimed that the TPP takes place as part of an unconscious psychological process and in fact respondents are not aware of their bias. News story. The news story used as stimulus material in this study was composed by the authors from several news stories and was written to present a balanced view regarding the issue of constructions of housing projects for the Jewish population in East Jerusalem. The title of the story was “as right and left continue their protests, Arab and Jewish residents go on residing in a pressure cooker”. The story mentioned that the minister of the interior is not approving new plans for construction in Jerusalem waiting for the report from a committee appointed by the prime minister, who is supposedly afraid of further tensions in the relationship between the Israeli government and the US administration. The story also mentions that, for similar reasons, the local planning committee was forced to go on recess for six weeks, and thus no new plans are approved and even approved plans are not signs. In accordance to the right wing narrative, the story mentioned housing shortage for Jews. A speaker from the right (Knesset Speaker MK Rubi Rivlin) was quoted, saying that the de facto construction freeze threatens the entire Zionist project as “there is no Zionism without Zion”. A speaker from the left (Mk Dov Hanin of Hadash Party) was quoted stating that “the protests in East Jerusalem are not only on the compound in Sheik Jarrah neighborhood but rather on “our ability to reach a two-state solution to the Israeli Palestinian conflict, a solution that includes two capitals in Jerusalem”. The story elaborated on right and left wing demonstrations in Sheikh Jarrah, mentioning that right wing see the conflict as a legal conflict to restore pre-1948 owner rights, and the left wing see it as a violent takeover. In accordance to left wing narrative, allegations that police is harsh on left-wing protestors while they let right wing protestors behave unruly without any response were mentioned. The story was pre-tested for neutrality and balance among a relatively uninvolved audience. Students from a large university in Northern Israel were recruited to read the news story and answer a pilot questionnaire (n = 208, mean age = 27.89, 51.4% female). Among them, 21 rated themselves as neutral (0) on a scale ranging between +5 for “very right wing” to “-5” for “very left wing”. Respondents were asked to read the news story and assess to what degree they thought the news story was biased in favor of the right (+5), in favor of the left (-5) or unbiased (0). On average, the neutral respondents ranked the story as unbiased (M = -.14, SD = 1.59), and this result was not significantly different from zero. Thus, it is possible to deduce that the news story was relatively evenhanded, as is naturally assumed in HMP studies. Measures. Hostile media perceptions. HMPs were measured using two survey items. First, participants were requested to evaluate to what extent the article they just read is neutral or slated for or against the position of the right on east Jerusalem (+5= slanted for the right, -5=slated against the right and 0= neutral) . Second, participants were requested to evaluate to what extent the article they just read is neutral or slated for or against the position of the left on east Jerusalem (+5= slanted for the left, - 5=slated against the left and 0= neutral). After reverse coding the second item, both items were highly and positively correlated (r = .69, p < .001) and hence were averaged to create a scale (M = - 0.39; SD = 1.63). Third Person Perceptions. To measure TPPs, respondents were asked to rate to what extent they themselves are influenced by the news story they have just read, on a 1= “not at all influenced” to 5 = “influenced to a great extent” (M =1.59, SD = .90). They were then asked to what extent is public opinion in Israel in general influenced by the news article. Answer categories again ranged between 1= “not at all influenced” to 5 = “influenced to a great extent” (M = 2.56, SD = 1.18). The first item was subtracted from the second to create a TPP score (M = .97, SD = 1.32). Covariates. As there are demographic differences between right-wing and left-wing supporters in Israel, and given that neither sampling nor assignment to the right/left groups was random, the analysis below controls for several demographic variables. These include sex (1=female, 46.0%), education (in years, M = 15.16, SD = 2.96), age (M = 45.21, SD = 16.02), household income (M = 3.16, SD = 1.23, on a 1 = “much below average income” to 5= “much above average income”), and dummy variables for religiosity (0=secular, 43.7%), having children (1=yes, 75.4%), army (1=yes, 77.9%) and other national service (1=yes, 11.7%), and country of birth (1= Israel, 79.8%). Results Unsurprisingly, the data supported both the TPP and the HMP. The difference between perceived influence on self (M =1.59, SD = .90) and others (M = 2.56, SD = 1.18) was statistically significant (paired-sample t (205) = 10.58, p < .001), indicating a highly robust third person effect. Right-winged respondents perceived the story as biased in favor of the left (M =-.88, SD = 1.54) while left-winged respondents perceived the story as biased in favor of the right (M =.43, SD = 1.37). The difference in HMPs between right and left wing respondents was statistically significant (t (200.16) = 6.42, p < .001). Thus, the evidence supports the HMP in the current data. However, our hypotheses predicted that participants in the information conditions would display significantly lower HMPs and TPPs. H1 predicted that exposure to information on research on the TPP would reduce the TPP. To test for this hypothesis, an ANOVA model was run with TPP as the dependent variable and the experimental condition as the independent variable, with the control variables as covariates. Results demonstrated that indeed, the experimental manipulation significantly affected TPPs (F (2,170) = 3.09, p < .05). Planned contrast comparisons demonstrated that respondents in the control condition displayed significantly higher TPPs (M =1.27, SD = 1.30), in comparison to both respondents in the TPP-information condition (M =.68, SD = 1.21) and respondents in the HMPinformation condition (M =.75, SD = 1.41). The planed comparison demonstrated that the difference between the TPP-information and HMP-information conditions was not statistically significant (p = .79). When probing into the separate effects of the educational manipulations on the “self” and “others” items, it turns out that the manipulation significantly affected the item measuring perceived influence on self (F (2,170) = 5.08, p < .01), while it did not impact the item measuring perceived influence on others (F (2,170) = .08, p > .10). Planned contrast comparisons demonstrated again that respondents in control condition ranked lower on the perceived influence on self item (M =1.32, SD = .64), in comparison to both information conditions (MTPP-information = 1.74, SD = 1.07; MHMP-information = 1.72, SD = .93), and that there was no significant difference in perceived influence on self between the HMP and TPP information conditions. H2 predicted that exposure to information on research on the HMP would reduce the HMP. To test for this hypothesis, an ANOVA model was run with HMP as the dependent variable and the experimental condition and the right-left variable as the independent variables, with the control variables as covariates. The means of the HMP variable by experimental condition are presented in Figure 1. As expected, the HMP, operationalized as the difference between right-wing respondents and left-wing respondents, was larger in the control group in comparison to both experimental groups. The test for the hypothesis is in fact the test for the interaction depicted in Figure 1. This interaction was significant (F (2,165) = 2.92, p = .05), supporting H2. To probe for the source of significance, a separate ANOVA model was run for control vs. HMP-information respondents. Results demonstrated a significant interaction (F (1,106) = 4.67, p < .05). That is, the slope of the HMP was significantly steeper for control participants, in comparison to HMP-information participants. Separate ANOVA models were also run for control vs. TPP-information and TPP-information vs. HMP-information respondents. In both models, the interaction between the political group (right/left) and the experimental manipulation was not statistically significant, though it approached statistical significance in the case of the HMPinformation vs. control model (F (1,110) = 2.61, p = .10). Discussion The results of the current investigation demonstrated that exposing participants to information about research regarding biased media perceptions reduced both the TPP and the HMP. That is, the misperception that media influence others more than oneself and the misperception that a particular news text is biased against one’s world view were both reduced significantly by a short intervention describing research about these perceptual biases. While obviously this is a short term effect that was obtained experimentally, and while the study could be criticized on grounds of artificialness and external validity, the results do highlight the potential of more long term interventions to reduce biased perceptions and images of media. As explained above, reducing such misperceptions is important, given research findings demonstrating that misperceptions of media have severe consequences for democratic life spanning from support of censorship to justification of violent forms of political protest. It is important to note that while the reduction in both TPP and HMP was significant and rather dramatic in magnitude, participants receiving the information still displayed TPPs and HMPs: Even in the HMP-information condition, the average right wing participants’ HMP was M = -.57 (SD = 1.31) while the average left-wing participants’ HMPs was M= .28 (SD = .93, F (1,64) = 15.17, p < .05), but this effect was not significant when controlling for all covariates. Even in the TPP-information condition, there was a significant difference between respondents’ perceptions of media impact on self (M = 1.74, SD = 1.05), and their perceptions of media impact on others (M = 2.52, SD = 1.26, t (64) =5.04, p < .001). That is, while exposure to information regarding research on the TPP or the HMP significantly and dramatically reduced biased perceptions of media, it did not cancel these biased perceptions altogether. This finding, that information about research on TPP and HMP can attenuate, but not cancel, these perceptions is similar to findings obtained in other research projects attempting to cancel the TPP (Tal-Or & Tsfati, 2007) or the HMP (Vraga, Tully & Rojas, 2009). Taken together with these past findings, the findings point out that the TPP and HMP are robust perceptual biases that are not easily corrected by a single snapshot intervention. Given that TPPs and HMPs both have cognitive and motivational antecedents it may be the case that the interventions correct only part of the reason for the perceptual error, and the remaining bias may be explained by other factors. Tal Or and Tsfati (2007) attempted to reduce the TPP by using the principle of substitutability of self preservation mechanisms. They reasoned that the fact that their manipulations reduced but did not cancel the TPP points out that part of the mechanism underlying the TPP is related to cognitive errors. Likewise, it may be possible to argue that the informational manipulation in the current investigation is successful in either reducing the cognitive reasons or the motivational reasons for the TPP and HMP (or it may simply attenuate both). Unfortunately, it is hard to know which of these possibilities underlie the present findings. It could be speculated that the manipulation affects the motivation to avoid being perceived as biased. This probable self-preservation strategy may overcome any self affirming value that the TPP or HMP may have. Alternatively, it could be argued that the information in the manipulation simply increases participants’ accuracy goals and hence, the manipulation reduces bias through more thoughtful cognitive processing. One clue in the findings that could somehow promote our understanding of the underlying is that the TPP-information manipulation affected the self-influence item but not participants’ perceptions of media influence on others. This finding is consistent with the effects of other manipulations that were supposed to attenuate the TPP (Tal Or & Tsfati, 2007). This may suggest that, as hypothesized by Pronin and Kugler (2007), reading the manipulation reduced participants’ confidence in the introspective data that (in the case of the TPP) is used more heavily when one assesses media impact on self. Another interesting set of findings that may potentially shed light on the underlying mechanism is that the TPP-information manipulation affected not only subsequent TPPs but it had also significantly reduced subsequent HMPs, while similarly, the HMP-information manipulation reduced not only subsequent HMPs, but also the TPPs. This suggests, again, that the findings indeed echo Pronin and Kugler (2007) findings, in the sense that information about the limitations of human reasoning in general attenuates biased processing, which may imply that, as Pronin and Kugler argue, the underlying mechanism may be that participants base their judgment less on introspective data and more on external information. Importantly, the fact that the HMP and TPP behave like other psychological biases reaffirms that HMPs and TPPs are indeed biases, a seemingly obvious fact that may actually be disputed, in particular in the case of the TPP (one may argue that participants in TPP studies are in fact less affected by media than people in general). Lastly, it is worth noting that Figure 1 demonstrates that the HMP-information manipulation was much more successful in reducing perceptions of media bias among right wing participants, in comparison to left-wing participants. Floor effects (relatively low levels of perceptions of bias among left-winged participants) are probably the reason for this finding. In other words, left-winged participants were not significantly affected by the manipulation (F (1,46) = 1.42, p >.10), compared to their right –winged counterparts (F (1,51) = 3.37, p =.07), because their baseline level of HMP was relatively low. It is well-established that the political right is much more distrustful of media in the Israeli context (Tsfati & Peri, 2006), as in other contexts (Lee, 2010). Among this group, the perception of the news text as biased against the right’s views regarding Jerusalem decreased by more than 50% as a result of the HMP-information manipulation. The findings’ main importance is the insight that information on communication research could serve as an antidote to biased media perceptions. This has implication for media literacy and education programs. Media literacy typically emphasizes production processes with the aim of increasing awareness of external influences on media, as well as increasing awareness of stylistic elements such as editing, composition, point of view, angle and connotation (see Silverblatt et al., 1999, p. 196; Hobbs & Frost, 2001). While research has documented that such interventions can potentially reduce perceptions of media bias (Vraga, Tully & Rojas, 2009), the current findings suggest that such interventions should also explain and educate about limits and biases in human processing and perceptions of media. Interestingly, the type of people who were affected in the Vraga et al (2009) study were completely different than those affected by our manipulation (it was liberals who were affected in their study and conservatives who were affected by our interventions). This points out that perhaps an intervention containing both information on production and information on the limits of the audience may be successful in completely eliminating biased perceptions of media altogether. References Bryant, J. & Miron, D. (2004). Theory and research in mass communication. Journal of Communication, 54, 662-704. Chia, S. (2006). How peers mediate media influence on adolescents' sexual attitudes and sexual behavior. Journal of Communication, 56, 585-606. Davison, W. P. (1983). The third-person effect in communication. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47, 1-15. Dillard, J. P., Shen, L., & Vail, R. G. (2007). Does perceived message effectiveness cause persuasion or vice versa? Human Communication Research, 33, 467-488. Golan, G. J., Banning, S. A., & Lundy, L. (2008). Likelihood to vote, candidate choice and the thirdperson effect: Behavioral implications of political advertising in the 2004 presidential elections. American Behavioral Scientist, 52, 278-290. Gunther, A. C. (1998). The persuasive press inference: Effects of mass media on perceived public opinion. Communication Research, 25, 486-504. Gunther, A. C., & Christen, C. T. (2002). Projection or persuasive press? Contrary effects of personal opinion and perceived news coverage on estimates of public opinion. Journal of Communication 52:177-195. Hobbs, R., & Frost, R. (2001). The impact of media literacy instruction on student media use motivations: An empirical investigation. Paper Presented at The International Communication Association Annual Conference, Washington, D.C., 2001. Huh, J., & Langteau, R. (2007). Presumed influence of DTC prescription drug advertising on patients: Physicians' perspective. Journal of Advertising, 36(3), 151-172. Kline, M. (2008). Jerusalem as an Israeli problem: A review of forty years of Israeli rule over Arab Jerusalem. Israel Studies, 13, 54-72. Paul, B., Salwen, M. B., & Dupagne, M. (2000). The third-person effect: A meta-analysis of the perceptual hypothesis. Mass Communication & Society, 3, 57-85. Perloff, R.M. (1989) Ego-involvement and the third person effect of televised news coverage. Communication Research, 16(2), 236–262. Pronin, E., & Kugler, M. B. (2007). Valuing thoughts, ignoring behavior: The introspection illusion as a source of the bias blind spot. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43 (4), 565-578. Rojas, H. (2010). “Corrective” actions in the public sphere: How perceptions of media and media effects shape political behaviors. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 22, 343-363. Salwen, M. B. (1998). Perceptions of media influence and support for message censorship: The third person effect in the 1996 presidential election campaign. Communication Research, 25, 259285. Silverblatt, A., Ferry, J., & Finan, B. (1999). Approaches to Media Literacy. London, England: M.E. Sharp. Sun, Y., Pan, Z., & Shen, L. (2008). Understanding the third-person perception: Evidence from a metaanalysis. Journal of Communication, 58, 280-300. Tal-Or, N., & Tsfati, Y. (2007). On the substitutability of the third-person perception. Media Psychology, 10, 231–249. Tal-Or, N., Tsfati, Y., & Gunther, A. C. (2009). The influence of presumed media influence: Origins and implications of the third-person perception. In: R. Nabi & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The handbook of media processes and effects (pp. 99–112). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Tsfati, Y. (2007). Hostile media perceptions, presumed media influence and minority alienation: The case of Arabs in Israel. Journal of Communication, 57(4), 632-651. Tsfati, Y. & Cohen, J. (2005a) Democratic consequences of hostile media perceptions: The case of Gaza settlers. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 10(4), 28–51. Tsfati, Y., & Cohen, J. (2005b). The influence of presumed media influence on democratic legitimacy: The case of Gaza settlers. Communication Research, 32(6), 794-821. Tsfati, Y., Ribak, R., & Cohen J. (2005). Rebelde Way in Israel: Parental perceptions of television influence and monitoring of children’s social and media activities. Mass Communication & Society, 8, 3-22. Xu, J. & Gonzenbach, W. J. (2008). Does a perceptual discrepancy lead to action? A meta analysis of the behavioral component of the third person effect. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 20, 375-385. Vallone, R.P., Ross, L. and Lepper, M.R. (1985). The hostile media phenomenon: Biased perception and perceptions of media bias in coverage of the Beirut massacre. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology ,49(3), 577–585. Vraga, E., Tully, M., & Rojas, H. (2009). Media literacy training reduces perceptions of bias. Newspaper Research Journal, 30, 68-81. Figure 1: Perceived bias by experimental condition 5 4 3 Perceived bias 2 1 0.65 0.28 0.38 0 -1 Right Wing -0.57 -0.54 -1.2 -2 -3 -4 -5 Experimental condition Left Wing Control group HMP forewarning TPP forewarning