Article Title: Shared Leadership: Paradox and Possibility Authors

advertisement

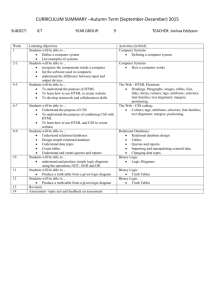

Article Title: Shared Leadership: Paradox and Possibility Authors: Joyce K. Fletcher & Katrin Kaufer Class: HOL6074 - Leadership Theory, Research and Practice Prepared by: Rick Sousane Context & Overview Purpose: Offers a way of thinking about the relational concepts and assumptions embedded either explicitly or implicitly in new models of leadership. Suggests that there are three powerful relational shifts that underlie models of shared leadership and we link these shifts to a number of paradoxes and dilemmas that arise in practice. Finally, apply what is a particularly useful theory of social interactions - Stone Center Relational Theory - -to inform the interactional nature of dialogue, one of the key coordinating practices of shared leadership. Audience: Leadership Theory Researchers & Academics Theoretical Base: Research: Stone Center Relational Theory This is a combination concept paper and research study Article Summary 1. New Leadership Practices a. Over the past two decades, a shill has occurred in how we think about, understand, and theorize organizational phenomenon. b. New models of leadership recognize that effectiveness in living systems of relationships does not depend on individual, heroic leaders but rather on leadership practices embedded in a system of interdependencies at different levels within the organization. c. Ushered in an era of what is often called "post-heroic" or shared leadership, a new approach intended to transform organizational practices, structures, and working relationships. d. 2. Shared Leadership: What Is It? a. Shared approaches to leadership question this individual level perspective, arguing that it focuses excessively on top leaders and says little about informal leadership or larger situational factors. In contrast, shared leadership offers a concept of leadership practice as a group-level phenomenon (Bryman, 1996; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 1999; Pearce & Sims, 2000; Scully & Segal, 1997; Senge, 1997; Yukl, 1998.) b. Although this recognition of leadership as a group phenomenon would seem to suggest an important theoretical and practical link between leadership research and research on group processes and teamwork, this connection is rarely made. c. Three shifts that have been identified elsewhere (Fletcher, 2002) as characteristic of the paradigm shift in relational interactions inherent in shared leadership. i. Shift I: Distributed and Interdependent – acknowledge the interdependent nature of leadership and signal a significant shift away from individual achievement and meritocracy toward a focus on collective achievement, shared responsibility, and the importance of teamwork ii. Shift II: Embedded in Social Interaction – emphasis on leadership as a social process. iii. Shift Ill: Leadership As Learning - focus on the skills and ability required to create conditions in which collective learning can occur. 3. Paradoxes of Shared Leadership a. Paradox I: Hierarchical Leaders Are Charged With Creating Less Hierarchical Organizations - As new models of leadership indicate, the skills it takes to engage in learning and leading need to be shared throughout the organization, creating leadership communities that move the enterprise forward. b. Paradox 2: Shared Leadership Practices "Get Disappeared" - Although at the macro level the rhetoric about leadership focuses on teamwork, collaboration, and collective learning, the everyday narratives about leadership and practices - the stories people tell about leadership, the mythical legends that get passed on as exemplars of leadership behavior -often remain stuck in old images of heroic individualism. c. Paradox Ill: The Skills It Takes to Get the Job Are Different From the Skills It Takes to Do the Job, or the "That’s Not How I Got Here" Paradox – jobs and careers are organized around principles of individual achievement and meritocracy. 4. Possibility: Rethinking Shared Leadership From a Relational Perspective a. Stone Center Relational Theory: What Is It? - model of human growth developed by feminist psychologists and psychiatrists at the Stone Center for Developmental Services and Studies at Wellesley College in Wellesley, Massachusetts. b. Tenets of Stone Center Relational Theory i. Self-in-relation – conceptualize self as a relational as opposed to an individuated entity. ii. Conditions - Mutual authenticity, mutual empathy, mutual empowerment. iii. Skills - Empathy, vulnerability, emotional competence, ability to contribute to the development of another with no loss to self-esteem, ability to operate in context of interdependence. Two-directional relational stance where interactions are approached as opportunities for mutual growth. iv. Outcomes - Five good things: zest, empowered action, increased selfesteem, new knowledge, desire for more connection. v. Systemic Power - Women expected to be the "carriers" of relational activity invisibly enabling the "myth of individualism" to endure and associating a relational stance with femininity. Unequal power relations (gender, race, class) leads to distortion of growth-in-connection principles, where parties with less power have more highly developed relational skills, thereby associating these skills with powerlessness. vi. Gender - Places the construct of relationality within the discourse on the social construction of gender, highlighting the fact that relationality is not a gender-neutral concept. vii. Power - In systems of unequal power (inequities based, for example, on race, class, gender, or organizational level), those with less power are required to develop relational skills in order to be attuned to and anticipate the needs, desires, and implicit requests of the more powerful. 5. Revisiting the Paradoxes of Shared Leadership - four aspects of shared leadership that must be revisited and ultimately rewritten from a relational perspective to address theparadoxes associated with this new model of leadership and capture its transformational potential. a. Rewriting the Image of Self - The more fluid, dynamic entity of self-in-relation, as differentiated from a self that is discrete and separate from others, provides an opportunity to re-conceptualize many of the concepts underlying shared leadership. b. Rewriting the Language of Leadership - The concept of self-in-relation also offers the possibility of identifying additional leadership skills and competencies. c. Rewriting Leadership Development - Identifying the need for a language of competence to describe relational practice highlights yet another aspect of the paradoxical nature of shared leadership. d. Rewriting the Language of Power - Stone Center Relational Theory points to a unique gender/power dynamic underlying new models of leadership. For example, the gender/power lens inherent in Stone Center Relational Theory offers a deeper understanding of the paradox of the disappearing of new leadership practices. 6. Possibility: Dialogue and Stone Center Relational Theory - explore the implications of using the tenets of Stone Center Relational Theory to understand dialogue, a process of communicating that (Yukl, 1998) argues is a prerequisite for shared leadership. a. Dialogue: Four Phases of Learning Conversations - Scharmer (2001) expands the research on dialogue by suggesting a framework that describes the process of dialogue (see Figure 2.1). He argues that when groups engage in a conversation, the quality or the interaction falls into four phases, each b. of which has distinctive characteristics. i. Talking Nice - participants in a group interact according to a given set of rules: “How are you? I am fine.” Everybody knows what to say, nothing is s surprise. No one, for example, stands up and says: "This is nonsense." Because individuals do not speak up or say what they really think, conversation devolves to a rule-repeating interaction. Characterized by downloading, politeness, listening is projecting, and focus on self as perceived by others. ii. Talking Tough - prerequisite for shared understanding because it allows groups to articulate opposing views and to talk with authenticity. Characterized by debate, clash, listening as downloading, and focus on advocacy. iii. Reflective Dialogue – new level of listening and mutual understanding. Characterized by inquiry, understanding others’ views, empathetic listening. iv. Generative Dialogue – transformational phase, which is characterized by flow, boundaries collapse, and co-creating. c. Using Relational Theory to Inform Dialogue – Stone Center Relational Theory can inform each of the four phases of Scharmer’s model. highlighting certain misprocesses and conditions within each and suggesting directions for future research on the interactional principles inherent in such models. i. The Four Phases - When the notion of sell-in-relation—and its corollary beliefs about interdependence, mutuality, and connection as the route to growth are added to the model, it highlights why an expanded concept of sell is needed to more hilly understand the kinds of social interactions that exemplify shared leadership practices that citable learning. ii. Possibilities - Substituting the concept of self-in-relation helps us see important aspects of individual interactions within the group and highlights the need to explicate the relational skills, competence and intelligence that would need to be developed in people who are part of these learning conversations. 7. Conclusion – a. Suggest that the concept of shared leadership can be informed by Stone Center Relational Theory in three specific ways. i. Offers a concept of self -in- relation that is more fluid and multidirectional than notions of sell as an independent entity. ii. Relational theory calls attention to the way in which the relational competence it takes to enact a self-in-relation stance is often dismissed and/or devalued by its association with femininity and powerlessness. iii. Offers a way of putting social interactions related to leadership in the broader societal context of power differences in which they occur. b. Shared leadership is assumed to have transformational potential - achieving this potential requires more than a cognitive awareness of the need for change because the paradoxes embedded in the concept are rooted in a complex set of dynamics that underlie workplace interaction. c. Future research on shared leadership must begin to integrate theories of group and team processes at the microlevel social interaction in order to understand and address the paradoxes inherent in shared leadership.