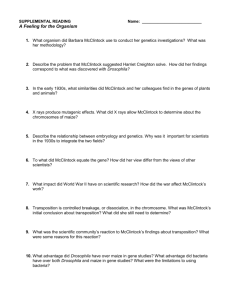

Barbara McClintock

advertisement

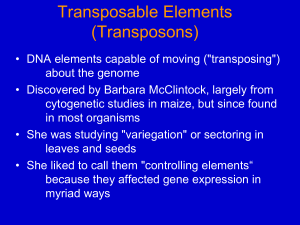

Barbara McClintock Barbara McClintock made a great name as the most distinguished cytogeneticist in the field of science. Her breakthrough in the 1940s and ’50s of mobile genetic elements, or “jumping genes,” won her the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1983. Among her other honors are the National Medal of Science by Richard Nixon (1971), the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research, the Wolf Prize in Medicine and the Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal by the Genetics Society of America (all in 1981) and the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University (1982). Early Life, Education and Career Achievements: Barbara McClintock was born on June 16, 1902 in Hartford, Connecticut. She was the third child of Sara Handy McClintock and Thomas Henry McClintock, a physician. After completing her high school education in New York City, she enrolled at Cornell University in 1919 and from this institution received the B.Sc degree in 1923, the M.A. in 1925, and the Ph.D. in 1927. When McClintock began her career, scientists were just becoming aware of the relationship between heredity and events they could actually examine in cells under the microscope. She served as a graduate assistant in the Department of Botany for three years from 1924-27 and in 1927, following completion of her graduate studies, was employed as an Instructor, a post she held until 1931. She was awarded a National Research Council Fellowship in 1931 and spent two years as a Fellow at the California Institute of Technology. After receiving the Guggenheimn Fellowship in 1933, she spent a year abroad at Freiburg. She returned to the States and to the Department of Plant Breeding at Cornell the following year. McClintock left Cornell in 1936 to take the position of an Assistant Professorship in the Department of Botany at the University of Missouri. In 1941 she became a part of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and began a happy and fruitful association which continued for the rest of her life. In 1950, Dr. McClintock first reported in a scientific journal that genetic information could transpose from one chromosome to another. Many scientists during that time assumed that this unconventional view of genes was unusual to the corn plant and was not universally applicable to all organisms. They were of the view that genes generally were held in place in the chromosome like a necklace of beads. The importance of her research was not realized until the 1960s, when Francois Jacob and Jacques Monod discovered controlling elements in bacteria similar to those McClintock found in corn and in 1983 McClintok received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of mobile genetic elements. Her work has been of high value assisting in the understanding of human disease. “Jumping genes” help explain how bacteria are able to build up resistance to an antibiotic and there is some indication that jumping genes are involved in the alteration of normal cells to cancerous cells. Death: McClintock died in Huntington, New York, on September 2, 1992.