Back in 2003, Wada banned gene doping.

advertisement

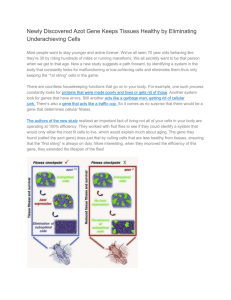

Read the article and then answer the questions. Who, if anybody, should be allowed to use this gene? Should the government control(FDA) its distribution just like a medicine? Why or why not. If you were an athlete, what other types of genes might you want to have available? If we allowed everybody to have access to the genes of the future, how would this affect sporting competitions? How do they make synthetic genes? 11 January 2014 Gene doping: Sport's biggest battle? By Tim Franks BBC News This could be a battle like no other in sport. The authorities are so concerned, they have been preparing for it for more than 10 years. But it is still unclear whether they have the tools to test for it - or whether anyone has done it successfully. It is gene doping. The idea is simple: to alter our genetic makeup, the very building blocks of who we are, in order to make us stronger or faster. The practicalities are highly complex. Gene therapists - for example those treating very sick children at London's Great Ormond Street hospital - add a synthetic gene to the patient's genome, and reintroduce it into the bone marrow via a disabled virus. The new gene is expressed by the patient's cells and acts like a medicine, permanently incorporated in the bone marrow. It is still a highly specialised, rare treatment, but the principle is being used for research into an ever wide range of diseases, including those where the muscles deteriorate. At which point, it becomes easier to imagine how athletes might benefit. Behind his glasses, Dr Philippe Moullier's eyes crinkle with energy and wry humour. He has the air of someone keen to be surprised by the work he is leading out of his tiny office at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm) in Nantes. Even he, though, was taken aback some years ago by the response to an academic paper he had published, as part of his work on gene therapy treatments for neuromuscular diseases. Scientists have used gene therapy to treat mice with muscular dystrophy Moullier had shown it was possible to produce artificially one particular gene - the erythropoietin gene - and introduce it into the body. And as anyone who had a vague brush with professional cycling in the 90s knows, the hormone erythropoietin, or EPO - which controls the production of red blood cells - was the illicit dope of choice for competitors. It was the wonder drug Lance Armstrong kept in his fridge, to boost his oxygen-carrying red-blood-cell count. The competition is so high, those guys are ready to do anything to make the difference” But while injected EPO has been detectable for years, introducing the EPO gene would result in the body producing its own EPO. Could this be an undetectable way of improving oxygen delivery? Shortly after Philippe Moullier published his paper, a bunch of visitors turned up to his laboratory in Nantes. They explained that they had been professional cyclists, had competed in the Tour de France, and were now part of an association fighting doping. At first Moullier says he was keen to share the science. He ended up feeling rather alarmed. "They were very excited. They told me that even though the technology was still at the research level, if it was accessible to the cyclists it would likely be used. I was completely shocked and surprised." Moullier says he warned that there was no way in which the therapy could, at that stage, be used safely. He was met with a collective shrug. His visitors, he suspected, were hiding their real motives. "They didn't seem to care, it didn't seem to be a problem for them. The competition is so high, those guys are ready to do anything to make the difference." And while making a permanent change to the genome may be complex - using a disabled virus to carry the genetic medicine to the cells - Philippe Moullier says there is now a shortcut, which delivers temporary results: injecting the purified gene directly into your muscle. In the years since he was visited by the ex-cyclists it has become possible for anyone to get hold of the EPO gene on the internet. The gene can be grown in your kitchen Even better for the would-be doper, says Moullier, this type of temporary boost may, after a few days, be hard for the authorities to detect. So what is the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) doing about it? It's unethical to withhold from someone something that would actually allow their muscles to be much healthier” Back in 2003, Wada banned gene doping. The agency argues that the practice would not just be unfair, it could be lethal introducing an extra copy of the EPO gene into your body could lead to too many red blood cells being produced and your blood thickening into sludge. As to whether there are tests for gene doping, Wada's Director of Science, Olivier Rabin, is more vague - deliberately so, he says. "For over 10 years we've been developing this technology, and we believe we have the tools to detect gene doping. And as to when it will be implemented, it's something that Wada keeps at its discretion. We need to validate this because as you know our technology can be challenged in the court." But there is a deeper question. Even if there were to be or already is a legally and biologically fireproof test for gene doping, what should happen if gene therapy were to become much more widespread, even routine? What if we were all able to buy, over the counter, genetic medicine to slow muscle deterioration? Should we - could we - stop athletes from using the medicine, to prolong their careers or speed a return from injury? Professor Lee Sweeney has been one of the leading researchers into gene therapy for two decades. Based at the University of Pennsylvania, he is one of Wada's team of expert advisers on gene doping. Like Philippe Moullier, he has experience of publishing research - and getting calls from people involved in sports. Sweeney's study, in the 1990s, was into how inserting the IGF-1 gene into the muscles of mice promoted muscle growth and slowed the ageing process. (The IGF-1 gene produces the hormone known as "insulin-like growth factor 1".) "We were contacted by numerous athletes, even coaches," Sweeney recalls. "They didn't understand that we were still at an early stage in terms of gene therapy moving to humans." Even now, he says, the medical research is moving very slowly in terms of using the technique for seriously ill people. "Back then, I hadn't even considered the fact that a young, ultra-healthy individual who's competing at the peak of their career would risk anything. But obviously many of them would risk everything." Brazil could be the first gene doping Olympics - if it wasn't London or Beijing This, though, is where Sweeney diverges from the current Wada orthodoxy. If gene therapy to prevent muscle deterioration were safe, he says, then it would become an ethical issue. There are some, he concedes, who believe it would be wrong to interfere, as they see it, with the ageing process as part of the natural human condition. But if change means, in Sweeney's words "sustaining normal quality of life for much longer", then he counts himself in favour. And this is where the issue swings back to sport. "From my own work with the mice, I also know that earlier you intervene, the better off you're going to be when you get old. So once you go down that path, I think it's unethical to withhold from someone something that would actually allow their muscles to be much healthier now and to the future. As long as there's no safety risk, I don't see why athletes should be punished because they're athletes. So I'm on the other side of the fence from Wada on this one, even though we're on the same team right now." Olivier Rabin at Wada argues, in response, that such ground will only need to be trod decades from now, given how slowly gene therapy appears in practice to be progressing. And when the time comes, he says, the agency will have to draw the line it does with all drugs: do they unfairly enhance performance? It seems, though, that the nature of gene doping will make drawing that line technically difficult and ethically awkward. The authorities, the athletes, the fans may need to agree a whole new definition of what we want sport to mean.