Summary online 16th to 19th century

advertisement

1

SUMMARY OF 'POVERTY IN ENGLAND

FROM THE 16TH CENTURY TO 20TH

CENTURY

PART ONE (16th to 19th century)

The following text has to be completed with your own

research. Some words or sentences are underlined,

highlighted , in bold types , in italics , etc. to

indicate the need for research. Research will be done

through websites given in your brochure. A brochure

and documents are available in the library (3rd floor).

Each century or period corresponds to texts in the

brochure.

I

INTRODUCTION

See brochure :

‘Bibliography’, ‘Glossary’, ‘documents’ .

See ‘PLAN DU COURS MAGISTRAL’

II THE 16th - 17th CENTURY : THE POOR

LAWS

I POLITICAL POWER in pre-industrial England : how conflicts

shaped the country : political and religious conflicts

A few facts about England in the 16/17th c : pre-industrial England

1

TUDOR PERIOD : 1485/1603 : 16th Century

Political history

The royal dynasty of Welsh origin which ruled England (and Wales) from 1485/1509 to

1603 . The most well-known of the Tudor monarchs were Henry VIII and his daughter

Elizabeth 1st.

2

The Tudor age was a very lively period in English history, a time of new learning, trade

and expansion.

2

ThE STUART/Stewart

Period : 1603 / [ 1714 ] :

17th Century

The royal family, of Scottish origin, which ruled England from 1603 to 1688 (apart from

the eleven years 1649-1660).

The (16th &) 17th century was a time of great conflict between Parliament and the

various kings, who tried to stop the growth of Parliament in a time when kings often

ruled on a principle of absolute monarchy.

the 17th century was also a time of civil wars and religious struggle but mainly without

the discoveries and inventions of the previous century.

MERCANTILISM

A

& ‘Tudor absolutism’

MERCANTILISM

see websites on economics

Before the Tudor period Holland occupied the dominant position in world trade, thanks to

its naval mastery. During the Tudor times however England is going to experience a gradual

accumulation of capital .

Several factors characterized the economic expansion of the Tudor times :

( historical

websites)

- commercial expansion (see Chartered companies)

-

technical discoveries and improvements in industry and agriculture

-

industry : see the cloth industry /the wool industry and trade

B

‘Tudor absolutism’

≠

French absolutism

Tudor Kings and Queens in effect reduced even more the power of feudal lords (nobility) &

the Church and encouraged trade. However they did not solve the problem of nepotism,

slowing the process of change in the economy and society.

A merchant class emerged very slowly, sharing somehow a common interest with the

monarchy -and not involving political power- . A common interest/belief developed as well

between the merchant classes and the puritans ( religion) even if loosely (cf brochure :

l’ascétisme protestant) .

The Tudor age is seen as a golden period (especially under Elizabeth I) with a growth of

wealth and population.

3

By the end of the 17th c the country still showed feudal characteristics but developed

capitalist features. Tudor ‘absolutism’ achieved a balance but prevented a certain freedom

(limitations due to absolute power).

2 The POOR From the 16th century to the 18th century

The’ Poor’ =the destitute (=les indigents)/The paupers ... : see ‘vocabulary ‘

and within this category : the ‘vagrants, rogues, vagabonds’ : the houseless poor ( the

bottom of society)

See brochure :

Les pauvres – le ‘ Welfare’

Introduction

A

Background

Cf Poverty in Elizabethan England + websites :

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk

or

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history etc.

( historical websites)

The tradition of the village supporting its poor had been firmly established from 8/9th

centuries (in Saxon times). The open-field system of farming was very much a communal

way of life to enable survival.

Legislation dealt with men without a work. (see ‘the Black Death’ (=la Peste

noire/bubonique) from the fourteenth century. Acts were passed aimed at forcing all ablebodied men (=robust) to work and keep wages at their old levels. Riots were recorded as early as

1378 as people rebelled.

The population lived within a system called ‘settlement’, originally created by the place of birth.

Elizabethan times tried to restrict the movement of ‘rogues and vagabonds’, defined as

‘wandering persons and common labourers being persons able in body using

loitering and refusing to work for such reasonable wages as is taxed or commonly

given in such parts’ (P. Slack ,Poverty and Policy in Tudor and Stuart England, 1988).

Several Acts were passed, such as the Act for the Repression of vagrancy (1597).

Punishment

was harsh and public .

These measures were meant to reduce the drain such people meant on the parish .

4

B The Tudors and the Stuarts : From voluntary relief to some degree

of involvement from the ‘state’ (kingdom)

CHARITY:

an act of faith

or

personal patronage

The poor depended on Private benefactors or the parish. Little by little, Charity moved from

its traditional voluntary framework to become a compulsory tax administered at the parish

level.

1.

The growing importance of THE PARISH

The

parishes were not of a standard size. Between the 17th and 19th centuries there were

an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 separate parishes in England.

Between 1536 and 1597 (H. VIII and E I) the government’s policy towards the poor changed.

H. VIII , by founding the Anglican Church reduced the power of the Catholic Church (see :

historylearningsite.co.uk : the dissolution of monasteries) . This meant huge changes for

the population.

2.

Worsening conditions in pre Tudor and Tudor times and the government’s

response : 3 factors.

1.The disappearance of monasteries... → worsening conditions for the poor in the 16th century.

2 the first wave of ENCLOSURES before and after the Tudor period (1490-1640.

See : sheep farming and the wool trade .

( historical websites)

3 Unlucky local conditions made things worse : though the Elizabethan population

increased by 25% (from 3 m to 4 million people), there were a series of disastrous

harvests in the 1590's , plus epidemics or the fire of London (1666) .

With the idea being pregnant (the control of the ‘commoners’),simple coercion could not

solve the problem and therefore a series of Elizabethan poor law acts were passed in 1563,

1572, 1576, 1597 and 1601.

C

THE ‘OLD’ POOR LAWS

( historical websites)

The idea of helping the poor but punishing ‘ the idle ‘ became pregnant

1.1 CATEGORIES

In 1563 A government statute categorized the poor for the first time into 3 groups :

5

1 The deserving, Helpless Poor

2 The undeserving, /Rogues and Vagabonds

(quoted as ‘those who could but wouldn’t work‘ by Elizabethan lawmakers)

3

The Able Bodied Poor

1.2. THE POOR RATES (= tax)

The act of 1572 introduced the first compulsory poor tax imposed on a national scale: local

poor law tax (the poor rates).

In 1576 the compulsion was imposed on local authorities to provide raw materials to give

work to the unemployed . In 1576 as well, the concept of the workhouse was born, and in

1597 the post of overseer of the poor was created.

The administration : the application was implemented by the local justice of the Peace [JP]

( justice in local tribunals), and was part of an income tax paid by those who owned land in

the Parish.

The great act of 1601 consolidated all the previous acts and set the benchmark

for the next 200 years.

There were other sources of charity : many churches had charity boards to help the poor.

To sum up :

The main objectives of the 1601 Act were:

The establishment of the parish as the administrative unit responsible for poor relief, with

Justices of the Peace relying on churchwardens or parish overseers to collect poor-rates and

allocate relief.

The provision of materials such as flax, hemp and wool to provide work for the able-bodied

poor.

The setting to work and apprenticeship of children

The relief of the 'impotent' poor — the old, the blind, the lame (handicapped), and so on.

This could include the provision of 'houses of dwelling' — almshouses or poorhouses rather

than workhouses.

the census of the poor

the punishment of the undeserving

These Acts, from 1597 and 1601, lasted well into the nineteenth Century.

6

D

The Settlement Act

1662

The Settlement Act and Removal Act : these acts consolidated the principles established

earlier on.

The 1662 Settlement Act stated that people had to prove "settlement" before receiving

relief from a parish. Settlement could be acquired in various ways (only ONE of the

following was enough) :

1. To be born in a parish of legally settled parent(s) or marrying in the parish (for

women)

2. Up to 1662 by living there for 3 years . After 1662 you could be thrown out within 40

days and after 1691 you had to give 40 days’ notice before moving in.

3. Renting property worth more than £10 per annum in the parish or paying taxes on

such a property ,by renting a property.( but this was well beyond the means of an

average labourer).

4. Holding a Parish Office. (being employed there)

5. Being hired by a legally settled inhabitant for a continuous period of a year 365 days.

(most single labourers were hired for 364 days)

6. Having served a full apprenticeship to a legally settled man for the full 7 years.

7. Having previously been granted poor relief. ( settlement examination).

Not having a settlement certificate put the poor in a difficult position as they could

be removed from a parish by the authorities (‘wandering’ was an offence).

2 examples :

illegitimacy

and

Parish apprenticeship

The 1697 Act also required the "badging of the poor”.

End of the seventeenth century : nearly a fifth of the whole English nation, was in

occasional receipt of relief.

7

III

THE 18TH CENTURY : THE

AGRARIAN/INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The kings : James I and his son Charles Ist, James II ... were so' inclined' to absolutism that

the Parliament signed a ‘petition of rights’ to protect its existence, and eventually appealed

to William of Orange and his English wife Mary, who became the 1st constitutional

monarchs. ('the Glorious Revolution' of 1689)

1. POLITICS

:

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER - THE HANOVERIAN HOUSE

also called

Georgian period

THE HANOVERIAN HOUSE

1714- 1837

Windsor since 1914

The main point is that England had became a constitutional monarchy, without a written

constitution. a Parliament with 2 Houses : the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Internal affairs were characterized by the growing importance and influence of Parliament

and the office of Prime Minister. A two-party system developed (though not ‘parties’ as

such, more at the end of 18th .c) : the Tories and the Whigs (cf Wikipedia ). Economic

changes took place, along with a political and social upheaval .

2.

THE INDUSTRIAL

AND

AGRARIAN

REVOLUTIONS

THE COTTAGE INDUSTRY AND THE ENCLOSURE MOVEMENT

THE INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

The INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION [ …1760-1850….. ] [1780/1790 : takeoff]

This is not a study of the I.R. at large , only the most important aspects for our lectures.

Brochure :

BRITAIN WAS A LARGELY RURAL ..., see map with areas concerned

The Industrial revolution (I.R.) often refers to Technical Inventions that changed England, and

improvements were real and essential but the IR was a global phenomenon , bringing changes in

social relationships . The two main factors were :

A

THE COTTAGE INDUSTRY

(or Domestic industry)

see vocabulary

see documents in file /brochure/ search websites) : Merchant capitalism, etc

8

A type of production developed in rural England and has become known by the general

term of ‘the Domestic (or Cottage) Industry’. (also called protoindustrialization –cf

Glossary) and took place throughout England in the 18th century (search maps)

It concerned :

Textile work ( usually divided up between the members of one family -weavers,

spinners, knitters specialized in the manufacture of certain products.

Metallurgy

Mining

A web of transactions developed and criss-crossed the country.

(see brochure and documents -3rd floor)

Technical improvements greatly influenced the transformation of the Cottage Industry

Transport improved too and new means of transport appeared .

However rural families always lived on the edge of poverty . With the gradual disappearance of the

domestic system, reactions and resistance took place .

B

THE ENCLOSURE MOVEMENT/SYSTEM

1 Background

2 The types of Enclosures

3 Changes in rural society

1.

Background /

What was it ?

:

It was a long and piecemeal process but resulted in the concentration of ownership and occupation.

see : The enclosure movement and maps, quotations, table, text : ‘la diffusion du progrès technique’

‘Enclosure’ literally meant that a field was surrounded by a fence or a hedge. It also meant that the

enclosed field was worked as a complete unit and no longer divided into strips. (see Common field

agriculture)

Changes occurred that accelerated the move .

9

2

The types of Enclosures

The most obvious factor is the physical enclosure of one land . Another type was the

consolidation of properties. Third was the piecemeal enclosure/mixed system . Those systems coexisted for a long time.

The legal system which was applied :

The 1nd method of encl was by private general agreement

(=accord à l’amiable général)

2rd method was by means of a private Act of Parliament (first in 1604 and it concerned 21 %

of England in 1914). The majority of these were given between 1750 and 1819.

3

How did it affect rural society ? What consequences ?

Arguments for and against the use of enclosure has always been pregnant in British history :

see brochure : quotations

An element which concerns us here with the disappearance of common land was the abolition of

‘use(r)-rights’ (communal rights) in villages. This meant the poorest lost an essential element of

their survival.

The population in villages rose partly because of the modification of the family economy, not

essentially because of 'improvements'. Serious social conflicts arose in the late 18/19th century.

Rural poverty increased, which in turn , gradually fed radicalism –the Chartists- in politics.

CONCLUSION

Parliamentary enclosure was not a dramatic shift from communal to individual ownership so much

as the emergence of a more precise definition of what constituted an individual’s property at

the time

(see quotation on brochure) :

[ “This marked the culmination of a certain form of capitalist property : property must be made

palpable....”. (E. Thompson)]

3

The speenhamland system

A. What led to the Speenhamland System ?

The period could be summed up as ‘Reform or Ruin !’ with a period of serious crises

(between 1760s-1810s ) which led to repression (of hunger marches and riots, poaching,

etc.) on the one hand and agitation for political reform on the other hand.

10

1782

GILBERT ‘ S

ACT (Thomas Gilbert)

The 1782 Gilbert's Act changed a certain number of features in the Elizabethan laws .

His proposals had been rejected partly because of politics and partly because of local

obstruction.

B The Speenhamland System

Cf websites for explanations

1795 -1834

It was a system of OUTDOOR RELIEF , a growing practice around this time known as the

Speenhamland system. In 1795, local magistrates decided to supplement wages when they

were clearly insufficient to survive, by the parish. It had many loopholes but spread quickly

through the south of England, and eastern parts of the country. However the unexpected

outcome was that it enormously aggravated the whole relief problem.

C The debate

There was a continuing debate and various answers throughout the 18th and 19th

century over the role of individual responsibility and collective provision for the poor .

Political thinkers and economists showed great concern about the state of the country, the

threat of an increasing population and the control of the mob : A. Smith, Thomas Malthus

or Jeremy Bentham, Robert Owen …

– (see ‘quotations’ in your brochure) and websites

A Some reformers wanted to remove relief entirely or partly :

- T.Malthus : ( Essay on the principle of population , 1798)

or

- J. Bentham (1748-1832) and the Utilitarians

B Other reformers argued otherwise :

- Robert Owen, a progressive factory owner or

- the journalist William Cobbett .

11

4

BRITISH SOCIETY AND ART IN THE 18TH CENTURY

See : DOCUMENTS ICONOGRAPHIQUES / ENGLISH PAINTING IN THE 18TH CENTURY

PAINTINGS

:

T. GAINSBOROUGH :

W.

1

HOGARTH :

Mr and Mrs Andrews

Industry and idleness

1748-1749

1747

POWER and 'CLASSES'

The word ‘class’ was known in the 18th century but people rather referred to ‘orders’ or

‘ranks of society :

the Aristocracy (=grande noblesse). In England the basis for power was more landed

property than a position within the hierarchy of the monarchy.

see : movies or novels : .eg. 'Barry Lyndon ' by S.Kubrick , 'The Duchess', etc

The gentry (= petite noblesse)

- the notion of ‘gentry’ is rather vague .

The gentry was a link in the circulation of money and power between Aristocrats and the

rest of the population. They gradually invested in lands and some became rich landowners.

See novels (by Jane Austen or movies based on her books, ‘Moll Flanders by D. Defoe …)

The middle classes were slowly growing, spreading their values of work, discipline, 'morality'.

Their claims to more power will only grow after the 1830s.

the ‘lower classes’ ‘ also called in the 16th/17th centuries the ‘meddling/middling and

industrious classes’ ) :

first of all

- the peasant world ( the yeoman –small landholder , the tenant and the

wage labourer)

-and later the industrial workers.

David Ricardo (the Principle of political economy and taxation, 1817) divided the society into 3

economic groups, according to their sources of income :

landlords, whose wealth came from rents (close to the French word ‘rentiers’),

capitalists whose income arose from profits,

labourers, dependent upon wages. However some landlords were also capitalists and

several professional classes were not, strictly speaking, wage earners.

12

2

CULTURE AND ART

There is a direct link between economy and politics on the one hand, and culture on the

other hand .

Consumption of art played a big part in the life and economy of the country . Aristocrat

patrons with available money and newcomers with purchasing power. Economic changes,

which culminated in large estates , transformed the English countryside (see ‘The Grand

Tour in the 18th century) with political and social implications.

The symbol of all the wealth and good taste was the COUNTRY HOUSE. The catchword

was IMPROVEMENT . The mid-18thcentury was golden age of the 'gentleman farmer ' .

PAINTING AND NATURE

This change affected the art of painting too .

2 emblematic painters :

see on websites :

William Hogarth (a satirist) :

'Industry and Idleness '

through Hogarth's vision we see the 'good', 'industrious' worker rewarded and the 'bad' ,

'idle' worker punished. But is Hogarth so convinced about this moral painting ? We know

nowadays that his criticism is not as straightforward as the 18th viewers thought...

Thomas Gainsborough

:

' Mr and Mrs Andrews'

The painting was an order from a rich 'gentleman', to show off his wealth and power.

Thomas Gainsborough subtly included some criticism...

13

IV THE 19TH CENTURY

See

: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/

:

‘All change in the Victorian Age’ (article)

http://www.victorianweb.org

British politics and society in the 19th century

1

BRITISH POLITICS IN THE 19 TH CENTURY

A

The French revolution in 1789 was a shock and brought fear and hope and the impact on

the country was felt through an intensified repression as well as demands for reform.

Whigs and Tories

The Whigs and Tories were the world's first political parties and over the years to come they

shared government and opposition in a dual party system.

Political life

:

Oppositions and distinctions at a political level :

18th century whigs were aristocrats (‘enlightened’ ones) but The Whig party was soon split

over the French Revolution. They were industrialists, financiers ... and the liberal middleclass of large towns in the 19th c.

19th century saw Changes for Tories too : for a long time rich conservative landowners , the

Tories were divided : moderates/reformers (Lord Palmerston or B. Disraeli 's ‘Young

England ‘) against 'hard liners’/’ultras’ (Lord Wellington) advocating repression :

landowners, conservative middle-class in the 19th c…

Economic life

:

Oppositions and distinctions at an economic level

The main battle/division took place over the repeal of the Corn Laws, the factory Acts and

the enlargement of franchise (right to vote).

INDUSTRIALISTS (rather Whigs)

versus

↔

LANDOWNERS (cons.)

14

Free trade

Corn Laws

Protectionism

Throughout the 19th century, REFORMS were implemented in various fields (children

work, adults, the franchise, housing, etc.). Radicalism played an important role.

Radicalism and Liberalism (political radicalism and economic Liberalism) had different

purposes but sometimes their ideology overlapped. Liberalism was close to the Whig

ideology of individualism, rationalization, progress. As far as poverty was concerned many

liberals believed in the ‘free labour market’ that would regulate the economy ‘naturally’ .

Anything that interfered with the laws of Supply and Demand was felt to be inadequate.

Which meant, taken to extremes, no factory regulations, no Trade Union, and no help to the

poor.

Utilitarianism developed in the early 19th c. and

Jeremy Bentham (1749 – 1832) (see website)

B

See

was associated with the philosopher

THE VICTORIAN AGE

websites (victorianweb.org) and documents ('All change in the Victorian Age')

Website :

Three main periods :

The early Victorian age

1815 or 1830s to 1851

The mid-Victorian age

1851 to about 1875

The Late Victorian age

1875 to 1901/1914

To sum up Victorianism, it is necessary to understand what the word implied at first, and

what it meant at the beginning of the 20th century.

The early Victorian age : started in 1815

[ or 1830s ]

There was much trouble at the end of the Napoleonic wars ( see : hunger marches, the

Luddite riots (1811), the radical meeting at Peterloo (1819)...)

In the 1830s 'Victorianism 'was building up, with great expansion but also huge

discrepancies. The middle classes were slowly bringing in their values :

WORK and MORALITY

(see : self-help, self-discipline , etc.)

15

Demography was high and urban society was growing.

The mid Victorian period (1850s-1875) : Work and Wealth (with a 'Puritan flavour')

See : Social reforms (e.g. ‘Public Health Act' in 1848) .

See : Britain as ‘the workshop of the world’

The catchwords were : Work and Wealth, Order, the Establishment.

1851 : for the first time, a census showed that the urban population has overtaken the

rural population. By the mid 19th century, industrialisation and urbanisation had altered

the lives of women and children as much as those of men.

(see : A. De Tocqueville or G. Doré).

The late period 1870s to World War I

A period of crisis with recession, international competition, a lack of entrepreneurs and disastrous

conflicts with colonies.

The adjective 'Victorian’ in the 20th c became synonymous with colonization, imperialism... the

opposite of the virtues it meant at first. The Fabian society and Socialism continued the radical

struggle of the former radicals

2.

The New Poor laws

See : Poor relief and Charity, Statistics, quotations… on brochure

1.

Sturges Bourne's Act

In 1819, in an effort to improve the administration of poor-relief (and reduce costs) the Sturges

Bourne Act 'To Amend the laws for the relief of the Poor '(59 Geo. III c. 12) made changes in the way

parishes were organized. Dissatisfaction was intense, both from the land-owning classes and the

labour force. Riots erupted in the 1830s especially in rural areas (the South and the East of the

country).

See 'les troubles ruraux en Angleterre dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle', E. Hobsbawm, 1968,

3e étage, B.S.

16

2. THE New Poor Laws of the 1830s

2.1

The Poor

- the notion of Poverty/Pauperism

At the beginning of the 19th c., The notion of poverty became loaded with a new meaning, a

rather ambiguous one, and was much discussed .Even in the morally rigid Victorian

century, Poverty was not a ‘crime’. But the idea of the ‘un/‘deserving’ poor, the concept of

poverty itself was not an easy concept to work with. Capitalism was trying to make a

difference between ‘industrious’ poor (the new factory worker) and the others.

Pauperism (= indigence ), the ‘idleness’ of the 18th c., became considered as a personal ,

individual flaw . It clashed with the Victorian values of Thrift(= economy ) for instance. The

increase of larger towns made poverty all the more conspicuous. They were not always more

numerous but more visible.

There were some statistics : around 1860, 25 % of the pop is supposed to have been

undernourished (meat consumption). The horrid working conditions in industrial areas

struck people’s mind (underlined by novels), though living conditions in rural areas were

even more precarious .

G. Best (1964) in a book about working-class homes :

‘Early Victorian cities were extraordinarily hostile to the Poor for it was always trying to tip

them over the edge of ordinary poverty into the abyss of hopeless, helpless poverty … Every

penny was a matter of survival or sinking- until or unless you gave up the struggle to survive.

An accident, ill-health, an epidemic, a dismissal….in a family meant absolute poverty and the

workhouse. '

2.2 The Commission of 1832

PM : Charles Grey (Whig)

See The Commission Report of 1832 brochure

It was in the face of this situation that the Whig government decided to intervene. In 1832 a

royal commission was appointed to inquire into the whole system. It sat for two years.

Two Commissioners to remember : Nassau Senior (economist) and Edwin Chadwick

(secretary), a disciple of Jeremy Bentham, who favoured a utilitarian principle of efficiency.

Officials concluded that the problem was not low wages and believed outdoor relief or

allowances were harmful to the poor. The report took the view that poverty was essentially

caused by the indigence of individuals rather than economic and social conditions. The

Royal Commission made a series of 22 recommendations which were to form the basis of

the new legislation. Some of its main proposals were:

17

The end of relief to the able-bodied except through a "well-regulated workhouse"

The grouping of parishes for the purposes of operating a workhouse (intensification)

The appointment of a central government body to administer the new system ...

and concluded :

"It may be assumed, that in the administration of relief, the public is warranted

(=justified) in imposing such conditions on the individual relieved as are

conducive to the benefit either of the individual himself, or of the country at large,

at whose expense he is to be relieved.'

"The first and most essential of all conditions ... is that his situation on the

whole shall not be made really or apparently so eligible [i.e., desirable] as

the situation of the independent labourer of the lowest class. Throughout

the evidence it is shown, that in proportion as the condition of any pauper

class is elevated above the condition of independent labourers, the

condition of the independent class is depressed; their industry is impaired

(=weakened), their employment becomes unsteady, and its remuneration

in wages is diminished. Such persons, therefore, are under the strongest

inducements (=incentive)to quit the less eligible class of labourers and

enter the more eligible class of paupers. ... Every penny bestowed (=given),

that tends to render the condition of the pauper more eligible than that of

the independent labourer, is a bounty (=bonus -butin) on indolence and

vice. ... We do not believe that a country in which ... every man, whatever

his conduct or his character [is] ensured a comfortable subsistence, can

retain its prosperity, or even its civilization./…/

Commission report 1832

2.3 The New Poor Law

(PLAA = Poor Law Amendment Act)

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 — An Act for the Amendment and better

Administration of the Laws relating to the Poor in England and Wales (4 & 5 Will IV c. 76)

The new Act imposed a nationwide uniformity in the treatment of paupers who applied for

relief. Outdoor relief was to be abolished eventually. It was based on the belief that the

deserving and the undeserving poor could be distinguished by a( ‘simple’) test, and 'anyone

prepared to accept relief in the workhouse must be lacking the moral determination to

survive outside it' (report).

The guiding principle of the new regime was that of "less eligibility" namely that conditions

in the workhouse should never be better than those of "an independent labourer of the

lowest class".

18

In order to deter paupers from coming to the

were taken (see websites and documents:

workhouse

very harsh measures

(‘The square plan) brochure

'the Workhouse':

www.workhouses.org.uk

(see pictures of Gressenhall, Norwich), 3e étage, B.S.

For instance :

• the separation of inmates into categories

• the wearing of a uniform

• a ban on tobacco and spirit, a ban on toys, books (except the Bible)

etc

The Administration of the Poor Law

The overall working and implementation of the new system was put into practice by means

of a large volume of orders and regulations issued by the Commission. Local parishioners did

not have a say in the running of the workhouse anymore.

New administrative units called Poor Law Unions, each run by a Board of Guardians locally

elected by rate payers with an overseer to administer the unit were planned. Each Union

comprised about 6 parishes.

The poor continued to belong to their parish and then the Union.

2.4

THE ENFORCEMENT

and

Opposition to the New Act

During the first 5 years of the Act, outdoor relief was abolished and 350 new Workhouses

were built, mainly in the South of the Country, where rioting had been a major problem, and

where many of the commissioners came from.

Workhouses were criticized from the beginning (costs, parishes joining slowly and

sometimes reluctantly, various scandals …) the workhouses were soon called the ‘Bastilles.

The Poor laws misunderstood the nature of poverty, which had different causes, according

to types of work, regions, seasonal versus regular employment -north versus south....

It was fought by Local Authorities and the Commission tried to issue Orders to regulate relief :

19

- The Outdoor Labour Test Order , 1842, to authorize outdoor relief under strict

conditions -a physical means test like stone-breaking or oakum picking (see Gressenhall,

Norwich)

- The Outdoor Relief Prohibitory Order 1844, to end all outdoor relief

The End of the Poor Law Commission

The ‘social novels’ of the 1840s (called 'the Hungry 40s') did a lot to warn the public about

the practices in the Workhouse as well as fierce hostility and organised opposition from

workers, politicians, radicals, religious leaders ( see brochure and documents + website on

social novels. In 1847 the Poor Law Commission was abolished and replaced by a new Poor

Law Board, accountable to the Parliament.

Conclusion

The workhouse was probably not as terrible as its reputation pretended. The standards

were not always bad ( food, clothing... ) and depended on each place. but as it aimed to

enforce a monotonous life, strict discipline, and useless tasks as well as a prison-like

appearance it was seen as unbearable .

Changes took place over the end of the 19th century (1865, 1876) and the beginning of the

20th century (the Edwardian period) but the principles of the 1834 law prevailed.

2.5

Victorian Philanthropy

Philanthropy (charity associations or private charity) developed considerably between 1830

and 1850, with probably twice as many volunteers as in France, for instance or elsewhere .

Through foundations, limited dividend companies, membership organizations, or by

bequests and donations, and were generally facilitated by middle to upper class people.

Charity organization movements were one of the key characteristics of Victorian era

philanthropist. So much so that a Charity Organization Society was set up in 1869 to

coordinate all these. Values observed were Victorian one ( ‘Victorian virtues ' of morality,

economy, self-discipline, temperance , etc. ).

Women played an essential role in Victorian charity (see Victorian novels). It was the only

‘respectable’ outdoor occupation for an upper or middle class woman ('visiting the poor') in

the rigid Victorian world. Friendly Societies' also played a part in helping the poor, whether

set up by the ruling class or by the workers themselves.

20

If the 18th century can be characterized by Art in the form of Landscape gardening and

Paintings, the most interesting factor characterizing the 19th century is :

THE SOCIAL NOVELS OF THE 'HUNGRY FORTIES'

The ‘social novels’ of the 1840s/1850s-60s

Affluence, leisure and education, as well as improvements in publishing turned the middle classes

into new readers, especially for novels. Interest in social problems corresponded to their

preoccupations. Victorians considered their age as a transitional one, a time of great change and

opportunities as well as unprecedented social ills.

In the mid-1840s a certain number of novelists focused on ‘the condition of England’ and its social

problems due to urbanization, industrialization, classes …

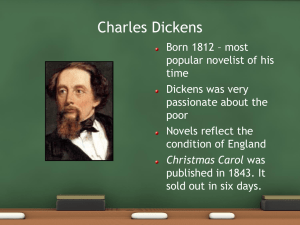

The most widely read novelist was Charles Dickens . His novels brought attention to

working-class life and the poor. He went on attracting his readers with the story of Oliver

Twist (1837) subtitled

‘Oliver Twist or the parish boy’s progress’. Its workhouses and

pickpockets addressed contemporary controversies over the Poor Laws and abandoned

children, problems.. He wrote many novels including also Dombey and Son (1846), which

attacks the figure of the callous captain of industry and discredits the period's prevailing

utilitarianism and materialism, and David Copperfield (1849), which exposes inequities in

England's class structure. During the same period Elizabeth Gaskell in Mary Barton

(1848) and North and South (1854) (see document) examined the huge gap between rich

and poor, the effects of Chartism, problems exacerbated by industrialization and the sudden

growth of industrial cities. Similar concerns dominate Charles Kingsley's 1848' Yeast', though

it focuses on the plight of rural laborers, and his 1850 Alton Locke, which exposes the crass

exploitation of sweatshops and squalid conditions of slums. ..

Benjamin Disraeli published a trilogy that focused, first, on the political and economic climate

since the 1832 Reform Bill (Coningsby, 1844); then on the evils of industrialism and dangers

of Chartism (Sybil, or the Two Nations, 1845) (see quotation on brochure); and eventually on

religion's role in ameliorating social problems ( Tancred, 1847).

21

CONCLUSION 19TH C

Despite rebellions and radical movements, writings by F. Engels and others, the working

class did not mainly join the radical movements . There was a general increase in living

standards, a desire to join the middle-class, a stability of the institutions, the power of the

empire and repression.

In a way the poor Law was a success since expenditure on the poor fell between 1835 &

1850. However the nature of poverty was never really tackled. Poverty in the 19th century

was judged on pragmatic or moral grounds , not with an ideal of social justice.

Toward the end of the century the hardest regulations were gradually relaxed. In 1891

supplies of toys and books were permitted in the workhouses. In 1892 tobacco and snuff

could be provided. In 1900 a government circular recommended the grant of outdoor relief

for the aged of 'good character'.

The Edwardian period (Edward VII, reigned 1901 – 1910 then

George V –Windsor, 1910 – 1936)

Society, after Victoria’s death was craving for change. The population increased from

16million in 1801 to 41.5 million in 1901. But 5% were unemployed an 20 % of the

population lived under the poverty threshold. The discrepancy between the rich and the

poor in terms of education, health, ... was greater than ever .

in 1909 David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, anticipating US President

Lyndon Johnson's " War on Poverty " by more than half a century, exclaimed in introducing

his new budget: "This is a war budget for raising money to wage implacable warfare against

poverty and squalidness....it is a war against poverty, not the poor”. Finally, the National

Insurance Act of 1911, providing sickness and unemployment benefits on a contributory

basis to a selected group of industrial workers, marked the birth of the Welfare State.

Nevertheless, It was not until 1930 that the poor laws were finally abolished. It was replaced

by Public Assistance laws. Outdoor relief was restored and only the aged went to the

workhouse. During the 1930s economic crisis, a Means Test was introduced to get Public

Assistance.

END OF THE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURY STUDY OF POVERTY

TWENTIETH CENTURY POVERTY WILL BE GIVEN ON ANOTHER PAPER