Poverty, Welfare & Democracy - Franklin & Marshall College

advertisement

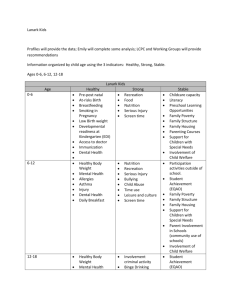

Poverty, Welfare & Democracy Poverty, Welfare & Democracy: How America Deals with its Poor Ameesh Upadhyay, Class of 2015 Bonchek College House March 29, 2015 Ameesh Upadhyay is from Kathmandu, Nepal. An economics major, he earned honors for his paper examining the effects of residential segregation on socioeconomic outcomes among African Americans and Hispanics. He also was a Seachrist Public Entrepreneurship Fellow at F&M’s Local Economy Center. Ameesh plans to pursue a Ph.D. in economics at American University in Washington D.C. Poverty, Welfare & Democracy “True individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. Necessitous men are not free men. People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.” So spoke Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his State of the Union address to congress in 1944. Poverty is a condition that deprives the individual from basic necessities for existence like food, water, shelter and clothing as well as other fundamentals to life like health, education, security, opportunity and freedom. The poor, who are without material resources or human capital, subsequently lack access to decision makers or other avenues of political influence (Piven & Cloward, 1963). Thus the relationship between the poor and the state has historically been characterized by mass protests, rioting and strikes among other disruptive tactics. The poor’s struggles for political and economic gains have not only been struggles of the poor against the state, but also struggles within the state. Once social disorder translates to electoral disorder, political actors vie to gain control of the electorate; politicians combine political rhetoric and posturing to placate protest movements while simultaneously appeasing economic interests irked by disruption. Thus the American welfare state has historically played a strategic role in determining the fate of the American poor. Today much of the ideological divide over the administration of poor relief manifests in two dominant political narratives. Supporters of the welfare state see poor relief as a humanitarian effort to elevate millions out of poverty and destitution, to provide the poor and unfortunate with a modicum of economic security if not opportunity. They argue that increased income will additionally translate to greater spending and spur economic growth. Opponents criticize public welfare provision for its inefficiency and view it as a bloated bureaucratic mechanism that not only takes money away from hard working Americans but creates welfare dependency and reduced labor-force participation in return, ultimately hurting the economy and undermining the free market. It is not the goal of this paper to argue along either line of reasoning, nor is it to provide a solution to poverty. In this paper I aim to illustrate that despite the popular view of relief provision as a humanitarian endeavor, welfare expansions in response to electoral instability created by the threat of rampant disorder. The provision of relief, or at least the promise of it, helps bring stability. Once electoral stability is restored, the state can safely cut back welfare provision. Thus, as a mechanism to maintain social order, the welfare state is fundamental to the longevity of a capitalist democracy. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, I will briefly outline the relative position of the poor in society, their relationship to the state, and the possible avenues for the poor to influence policy. Next, drawing largely upon the works of welfare activists and scholars Frances Fox Piven & Richard Cloward, I will briefly discuss mass movements that led to major welfare expansions 1) The Unemployed Workers Movement and the Industrial Workers Movement of the 1930s that culminated in the New Deal legislation, and 2) The Civil Rights Movement and the Welfare Rights Movement of the 1960’s. Finally I will briefly the role of the poor in today’s democratic society. Poverty, Welfare & Democracy Being Poor in America More than forty-five million Americans, or fourteen and a half percent of the American population, lived in poverty in 2013. Much of this poverty can be attributed to the depression of 2008; in fact in 2013, poverty declined for the first time since 2006. The fact that the business cycle and economic crises produce widespread deprivation has been widely recognized since the eighteenth century. But Americans attribute poverty to a variety of other reasons as well. A survey conducted in 2000 by Kaiser Family Foundation and Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government found that about 48% of Americans thought poor people were simply not doing enough to get out of poverty. 46% thought the welfare state was a major reason for continued poverty, 52% mentioned lack of motivation and 57% stated decline of moral values as a major cause of poverty. Americans’ attitudes towards the poor are a reflection of an individualistic culture that strongly upholds independence as a virtue. If America is indeed a place where honest hard work translates into upward social mobility, then surely a lack of effort must play a role in persistent deprivation. Thus the poor are socially constructed as dependent and weak not only economically but also morally, as they do not subscribe to the American ethos of independence. As these narratives are reinforced by media outlets and political rhetoric, not only are the poor perceived to be worse off due to some fault of their own, but any welfare program intended to elevate their socioeconomic status becomes politically undesirable. On the other hand, the poor’s perception of their own condition reflects something else entirely. On the same survey, respondents with lower incomes were more likely to attribute poverty to a specific, concrete issue. Asked the same question, 74% of the poor thought drug abuse was a major reason, 71% mentioned medical expenses, 70% mentioned too many low paying and part time jobs, and 64% mentioned single parenthood. Poverty may be the end product of larger social, economic and political processes, but it is experienced by individuals in a finite, concrete setting. As Piven & Cloward write in their book titled Poor People’s Movements (1977), “A worker experiences the factory, the assembly line, the guards, the owner and the paycheck. He does not experience monopoly capitalism.” Similarly a poor patient experiences the hospital waiting rooms, the nurses, the doctor and the medical bill without understanding the healthcare system, just as a welfare recipient may experience the long waiting lines, the disapproving caseworker, and the welfare check without understanding American welfare policy. Thus when deprivation and injustice –real or perceived- leaves the poor no choice but to protest, they protest exactly in the settings where they experience that form of deprivation or oppression. Workers may go on strike and withhold their labor to demand higher wages, for a stop in production results in a cut in profits. A cut in profit compels a profit-oriented owner to restore production either through negotiation or by appealing to the local or state authorities who would otherwise ignore the poor. More often than not, the state acts on behalf of the economic interests it represents, using coercive means to curb protest and restore production. Concessions are only made when absolutely necessary. If concessions are rarely made to the working poor, they are even more elusive for the unemployed, who do not provide any labor to withhold and can only crowd welfare offices to demand relief. But it is during times of greatest discord that the most concessions are made, for disorder can alter electoral preferences, and political leaders have much to lose in such circumstances. As the following discussions of movements shall illustrate, such was the case in the New Deal as well as Great Society legislations. Once the same movements abandoned disruptive measures and got organized in hopes of exerting influence Poverty, Welfare & Democracy through lobbying, not only were their requests completely ignored but much of the progress made previously was gradually whittled away. In many cases the leaders of the movements ironically played key roles in impeding reform. Leaders of these movements often underestimated not only the leverage provided by disruptive power but also the resilience of the American political machine and its capacity to pacify and gradually erode the movements they led. In the words of Piven & Cloward, they failed to win what they could have won when they could have won. The Unemployed Workers Movement, the Industrial Workers Movement, and the New Deal To many the New Deal represents the ushering of a new era of capitalism, fundamentally transforming the economic and political institutions of America (Polanyi 1944). The great depression signaled to the leaders of America that capitalism necessitated some level of regulation of labor and labor and capital alike. The crisis started on a fateful Thursday in October of 1929, known widely as “Black Thursday”, when the stock market burst in panic. Over the next two weeks, over 2.5 million Americans lost their jobs. Roosevelt’s Council on Economic Security later estimated that the number of unemployed jumped from 429,000 in October to 4,065,000 in January, and continued to rise to 9 million the by the next October. By 1933 this number had reached 15 million, and 40% of the male labor force had found themselves out of work. Surveys of school children revealed that about a quarter suffered from malnutrition. Family ties were disintegrating, and beggary and vagrancy were becoming a common sight (Piven & Cloward, 1977). Political leaders, most notably President Hoover, initially refused to acknowledge the problem and contended that the census numbers reflected, “the shiftless citizen, who had no intention of living by work, as unemployed.” Since the problem was defined as minor, the efforts made to deal with the problem were also minor, limited mostly to local charity efforts. To be fair, Congress did in fact pass two measures to alleviate unemployment by expanding federal public work programs. Hoover vetoed one, and appointed an anti-public works administrator to implement the second (Piven & Cloward, 1977). Meanwhile American families haunted the employment offices, exhausted their life savings, sold their belongings and were forced on to the streets. Those who still had their jobs had their wages cut, but they stayed quiet for the fear of losing what they had. By March of 1930 the rioting had begun, led primarily by communists. Men and women in New York, Detroit, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Chicago, Seattle and Boston were marching under communist banners titled “Work or wages” and “Fight, don’t starve”. Initially the demonstrations were peaceful, but before long local officials started ordering the police to use force. The worst clash occurred in New York, where 35,000 unemployed marched on to City Hall only to be met by hundreds of policemen. The New York Times reported: “From all parts of the scene of battle came the screams of women and cries of men with bloody heads and faces. A score of men were sprawled over the square. The pounding continued as many sought refuge in flight.” Later in 1932, thousands of veterans and their families descended on Washington, demanding their benefits, chanting “Mellon pulled the whistle, Hoover rang the bell, Wall Street gave the signal, and the country went to hell.” Congress turned them down, Hoover refused to meet with their leaders and instead ordered the Army to rout them. The Washington News Poverty, Welfare & Democracy observed, “What a pitiable spectacle is that of the great American Government, the mightiest of them all, chasing men women and children with army tanks. If the army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America” (quoted in Piven & Cloward 1977). The riots across the country intensified to the point where local authorities had no choice but to provide relief to the thousands lined up on city streets, especially in industrial cities where the working poor comprised voting majorities. By 1932 nearly 1,000 local governments had defaulted on their debts, and turned to the federal government for help (Piven & Cloward, 1977). Social disorder was giving way to electoral disorder. The Republican Party, with eastern businessmen at the helm, had ruled with substantial majorities until the election of 1930. But the depression combined with the frustrations of local and state governments, as well as the Hoover Administration’s inadequate response to the crisis, triggered perhaps the most significant voter realignment the country had ever seen. The man who rose to power aboard the shifting currents was of course Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had promised to “build from the bottom up and not from the top down, that put their faith in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid” (quoted in Piven & Cloward 1977). Indeed he had promised everything he could to everyone he could. Three weeks after assuming office, he instituted the Civilian Conservation Corps, a public works program that provided 250,000 jobs at subsistence wage. The Federal Emergency Relief Act signed on May 12 allocated $500 million to states for unemployment relief. Total expenditures rapidly rose to over $3 billion by the time the program was terminated in 1936. As part of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), industry workers gained collective bargaining rights and industry codes for regulating minimum wage as well as maximum hours. For business, NIRA granted the right to limit production and fix prices. That the federal government had made such promises provoked enough sympathy from poor workers and the unemployed alike. Workers surged towards unionization. Membership rolls in the Union of Mine Workers increased 5 fold, in the International Ladies Garment Workers it quadrupled. The Amalgamated Clothing Workers saw their membership increase from 300 workers to over a 125,000. Over 200 unions sprang up in the Auto industry, while about 70,000 joined the Akron rubber plant unions, 300,000 textile workers joined the United Textile Workers of America, and 50,000 joined in steel unions (Piven & Cloward, 1977). Meanwhile the socialists and communists that led the unemployed movements clamored to form a national organization, and their efforts culminated in hundreds of unemployed councils being consolidated into the ranks of the Workers Alliance of America (WAA). But by forfeiting disruptive tactics and adopting bureaucratic ones, the unemployed relinquished the little leverage they had over policy makers. The expanded relief system and the new aura of sympathy provided by the Roosevelt administration tempered indignation amongst the poor. The WAA made every effort to obtain reform through lobbying. It drafted relief bills on its own, and pushed for resolutions that allowed those on public work programs to remain on the program if they were unable to find work elsewhere. But without the disruptive power of the strike at hand, the WAA was completely ignored. Not only were none of its recommendations considered, but officials also refused to associate themselves with the organization. The WAA had no achievements to show its members, and it could not boast any influence in Washington. Roosevelt gradually cut back appropriations for the WPA, and repealed direct emergency relief entirely in 1936. The WAA was quietly dissolved in 1940 (Piven & Cloward, 1977). Poverty, Welfare & Democracy In contrast, industrial labor was better off, but what was promised in principle was not enforced in practice. Through the 1930’s, industry employers refused to recognize unions and continued to fire employees on the basis of union affiliation. Somewhat ironically, the leaders of American Federation of Labor, the largest union grouping in the United States denounced industrial unionism to preserve their close ties to elite business groups. Workers, with the confidence of federal law behind them, intensified their protests. In Toledo, Ohio, a crowd of 10,000 was met by the Ohio National Guard, killing two and wounding many more. A crowd of 20,000 in Minneapolis were also fired upon by the National Guard, killing two and wounding 67 workers. In San Fransisco, 135 were hospitalized and two killed. 1700 National Guardsmen marched into the city to restore order (Piven & Cloward, 1977). These are but few of the conflicts that occurred. In almost all cases where they did, local authorities unequivocally sided with employers. The intensifying protests however, forced the federal government to act, at risk of losing popular support. The National Labor Board was instituted in 1933, to advocate for collective bargaining. Despite some initial success the NLB (Later reorganized into the NLRB) lacked legal authority and could not do anything when employers simply defied it. The administration lost support from business, and if worker demands went unappeased, it risked losing labor support as well. In 1935, Roosevelt signed the Wagner Act, granting the NLRB legal authority to enforce union recognition, along with other aspects of the NIRA. But business vehemently opposed the bill, declaring it unconstitutional. To make matters worse for labor, the Supreme Court struck down the NIRA as unconstitutional. But Roosevelt’s re-election in 1936 signaled to labor that business had lost control of the state. Protest further intensified both its frequency increased - there were 2,014 strikes in 1935, 2,176 in 1936 and 4,740 in 1937. Compelled to act, the White House coaxed industry owners into agreement with union workers over many of the strikes across the country. Whatever sympathy labor had perceived to have gained from the administration, however, had disappeared by 1939. With an impending war in Europe and surging demand for steel and raw materials, after 1939 Roosevelt rapidly ordered federal troops to force plants to remain open. The NLRB was reconstituted to eliminate its pro-labor members, and the Supreme Court ruled sit-down strikes illegal. Anti-communist propaganda helped purge communist and socialist leaders from unions, and Roosevelt used the upsurge in nationalistic sentiment to sign a no-strike pledge from the AFL. The unions themselves started to discipline labor. At the end of the war, unemployment surged and so did the rioting but Truman used his war time powers to seize plants and force them to open, and threatened strikers with the draft (Piven & Cloward, 1977). With the electorate intact, however, no more concessions were made to labor. In fact what they thought they had won for themselves, their families and their children, were whittled away. The forgotten man at the bottom was once again forgotten. The Civil Rights & The Welfare Rights Movements The next great struggles occurred among Blacks in the 1950’s. Theirs was a struggle to secure political rights in the South, as well as to secure economic advances. Therefore it was not just a struggle of blacks in a white society, but also of the poor in an affluent one. Just as World War II brought the great depression to a rapid end, rapid industrialization and the mechanization of agriculture brought about unprecedented socioeconomic and demographic changes. Demand Poverty, Welfare & Democracy for industrial labor in the north rapidly increased while agricultural labor in the south declined throughout the first half of the 20th century. In 1900, 87% of blacks were engaged in southern agriculture or were household servants. In 1960, less than 10% were employed in agriculture. While 90% of blacks lived in the south in 1900, about half were living in the north by 1960 (Piven & Cloward 1977; Massey and Denton 1993). An overwhelmingly rural and oppressed peasantry was transformed into a depressed urban minority. This change is significant for two reasons. First, modernization shifted the electoral balance in the south from rural sharecroppers to urban industrial and business elites. Although the caste system benefited both, the business elites relied mainly on market mechanisms for its labor, and it was in their interest to avoid segregation if it kept labor or northern businesses away. The Democratic Party’s firm hold in the south was further undermined by black migration to the urban north, as the party found itself endorsing segregation in the southern electoral base while denouncing it in the northern one. Second, it allowed for mass mobilization of blacks in urban areas, where they were more likely to be heard by political leaders and to force them to act. In 1954 the Supreme Court struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine. This development added legitimacy to the cause of desegregation, and encouraged southern blacks to demand their rights. In 1955 when Rosa Parks was arrested in Alabama under local segregation ordinances for refusing to sit in the section of a bus that was restricted to blacks, mounting indignation culminated in rapid mobilization of city-wide boycotts that drew national attention. The Supreme Court declared Alabama’s bus segregation laws unconstitutional. This victory for blacks triggered a wave of white extremism and violence in the south, bringing race to the center of the political debate. Congressional Republicans pushed for a civil rights bill in Congress, exacerbating tensions within the Democratic Party, but Senate majority leader Lyndon Johnson ultimately killed the bill with the help of southern Democrats. Another civil rights bill was introduced before Congress in 1957, and this time Johnson was able to gain support for a symbolic compromise bill (Piven & Cloward, 1977). The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 encouraged black mobilization. Disruptive tactics mushroomed under SNCC activities of civil disobedience. Across the country, students staged sit-ins, and refused bail when arrested. Kennedy finally reached out to black voters in 1960, right before the election, turning the tide of black voter perception towards the democratic nominee. The administration attempted to divert attention from civil rights to poverty legislation, encouraging many poor blacks and some whites to attack the welfare system in the early 1960’s in hopes of alleviating their severe economic hardship. But the Kennedy Administration was repeatedly drawn into civil rights conflicts, and when he did finally made his support clear, southern movements intensified under a new sense of legitimacy. King’s march in 1961 and subsequent marches in Albany resulted in thousands of arrests and many injuries. In Birmingham over 2,000 were jailed in 1963. In June Kennedy announced his request to Congress regarding a comprehensive civil rights bill. In the midst of all the turmoil, Kennedy was assassinated in November of that year. Suddenly Johnson, a southern democrat who had opposed civil rights legislation on almost every count during his career in Congress, found himself with no choice but to commit his administration to civil rights. With the support of northern Republicans, the Civil Rights Act passed Congress, and Johnson signed it on July 2 1964. But southern authorities refused to comply, and the protests continued. In the first four days of February 1965, 3,000 blacks protesting illegal voting restrictions were imprisoned in Selma, Alabama. The movement Poverty, Welfare & Democracy forced Governor Wallace to request federal support. In response, Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard and ordered them to escort the protestors as they marched to Wallace’s capitol building. Congress passed a voting rights act in August (Piven & Cloward, 1977). The acts guaranteed blacks the right to vote in the South, but provided no economic gains. Johnson’s war on poverty expanded relief provision, and provided support to the belief that poor had a right to welfare. The NWRO had emerged as a leading welfare rights group, which initially directed its efforts towards disruptive tactics. A multifaceted campaign against welfare restrictiveness emerged. Demonstrations swept across the country. Many died, and many more were injured, but government conciliation spurred the poor to fight for what they perceived was their right. State legislatures conceded the flat grant system that provided a grant of a mere $100 dollars a year in 4 installments (Piven & Cloward, 1977). The leaders of NWRO started to divert their efforts from disruption towards creating a nationwide organization that lobbied for the rights of the poor, blacks, women and children. But as civil rights and welfare rights riots subsided in the late 1960’s, public opinion had started to turn against blacks and the poor. Rhetoric emphasizing law and order and self-reliance emerged once more, and Nixon won the election of 1972 after popularizing slogans like “Workfare not Welfare” during his campaign. Nixon reversed policies that had made concessions to the poor, restricting the substantive and procedural rights which welfare recipients had won through protest and litigation. Quality controls were enforced on states’ administration of welfare. Governors like Ronald Reagan developed reputations for anti-welfare campaigns in their states. Funds for Great Society programs were drastically cut back, and local administrators refused support to organizers. Politicians fostered the narrative of welfare dependency and parasitism to support programs that cut welfare expenditure. Piven & Cloward wrote, “The belief grew [among the poor] that the fight was being lost- even perhaps that it was no longer worth being fought.” Welfare was increasingly believed to keep people out of work, and fathers were believed to have abandoned their families in order to make them eligible for welfare. By inflaming public opinion, Nixon aimed to let local officials respond to the uproar by slashing the rolls. The NWRO’s lobbying efforts fell on deaf ears in Washington, and internal issues regarding membership maintenance and conflicting interests among leaders eventually brought about its demise in 1972. Poverty and Democracy Several parallels can be drawn between the poor people’s movements of 1930’s and 1960’s. Both came about in times of severe hardship caused by socioeconomic changes. In both instances the poor were able to make the most significant gains in civil, political and economic rights exactly when they were the most disruptive and the electorate was unstable. While the state was forced to deal with the crises generated by the movements, it did not have to deal with the demands of the organizations that led the movements. To be sure, the gains made in both those times were historic; millions of Americans gained a semblance of economic security in welfare, the enfranchisement of blacks represented the first step towards uplifting the most exploited racial group in American history, and collective bargaining gave a democratic element to a largely authoritarian workplace. But the poor might have achieved much more had they not abandoned their disruptive methods for organizational ones. Once indignation gave way to docility, the welfare state had served its purpose. The state contracted welfare, and America resumed business as usual. Poverty, Welfare & Democracy So what then of the poor today? Ideally we would have the poor’s vote command as much electoral influence as any other American. In practice this is hardly the case. Rising corporate and elite influence in the Democratic and Republican parties’ ranks weakens the prospects of legislation catering to the interests of the poor. In fact the lack of influence on policy extends well beyond the poor, a recent Princeton study found that the vast majority of Americans have virtually no influence on policy (Gilens & Page, 2014). Furthermore, the firm allegiance of the poor to the Democratic Party diminishes their influence on policy. The poor, like any other group, would be better served if both parties vied to gain their vote, as was the case with blacks in the 1950’s. Although it was conservatives like Bismarck and Churchill who championed the welfare state in Europe to counter instability and the threat of radical communist movements, American conservatives have largely opposed the expansion of welfare on moral and fiscal grounds. But the poor are not the only ones whose well-being derives from welfare programs, and neither does the American welfare system provide enough to poor families for it to be a suitable alternative to work. As long as such myths pervade the political narratives and beliefs of Americans, the poor are bound to be socially constructed as dependent and any public efforts to elevate their status will be deemed immoral. Rising inequality and the changing demographic of America may bring much to bear on such beliefs over the next few decades, and the welfare state will again occupy the center of the political debate. Can any gains for the poor be made through these debates in the halls of our democratic institutions, or does the well-being of the poor in the 21st century depend on their ability to disrupt the functioning of those same institutions? This much remains to be seen. References Gilens, M. & Page, B.I. (2014). Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens Massey, D.S. & Denton, N.A. (1993) American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press NPR/Kaiser/Kennedy School Poll (2001) Poverty in America. Retrieved April 15th 2015, from http://www.npr.org/programs/specials/poll/poverty/summary.html Piven, F.F. & Cloward, R. (1971) Regulating the Poor: The Functions of Public Welfare. New York: Pantheon Books Piven, F.F. & Cloward, R. (1977) Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail.