Supplementary methods

Online supplementary material

Supplementary methods

Insect handling and pheromone bioassays

We collected Lasius niger and L. flavus workers by excavating colonies in

Tvärminne, SW Finland, in July 2014. Approximately 100 workers from each colony were randomly, evenly divided between two 8×10cm plastic containers with ad libitum access to egg-honey-agar food medium and water. These nest boxes were randomly assigned to a pheromone treatment; one received synthetic queen pheromone (0.01g l -1 racemic 3-MeC

31

in hexane), and one received a hexane-only control (as in [1,2]), applied to a glass coverslip placed in the center of the nest. We applied 10ul of pheromone solution (i.e. 0.1ug 3-

MeC

31

) or hexane to the coverslip every 24h for 21 days (duration chosen in light of data from [1,2]), at which point the ants were freeze-killed at -80 o C. 3-MeC

31 was synthesized as previously described (Holman, Hanley & Millar, submitted).

For Apis mellifera honeybees, we collected newly emerged workers from three hives at an apiary near Hebden Bridge, UK, in July 2014, and randomly divided them between two plastic 12×25cm aquaria with ad libitum water, royal jelly and honey and a paper-lined floor (c. 30 workers per aquarium). Cages assigned o to the queen pheromone treatment received a 2cm strip of ‘Bee Boost’ (i.e. synthetic queen mandibular pheromone on plastic; Thorne, UK) at the start of the experiment and every subsequent day for 3 days (before freeze-killing at -80

C), while controls received a 2cm piece of plastic. The 3-day duration was chosen based on data in [3] showing a strong effect of queen pheromone on worker gene expression profiles on day 3 relative to days 1, 2 or 4 postexposure. We thus used a split-colony design for the two Lasius species and A.

mellifera, such that each colony received both treatments.

Complete, queenless Bombus terrestris bumblebee colonies were similarly treated daily with either a hexane control or a synthetic queen pheromone (C

25

) dissolved in hexane, and freeze-killed at -80 o C after 14 days (full methods in [4]).

To avoid disturbance we did not split Bombus colonies; we simply assigned five colonies to each treatment at random.

Quantifying expression of DNA methyltransferase genes

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (TriSure, Bioline) from crushed complete individual workers of A. mellifera and Lasius spp. Due to the larger size of B.

terrestris, individuals were bisected longitudinally, and a random side was used for RNA extraction. 1ug of RNA was treated with 1U of DNAseI (Thermo

Scientific) and converted to cDNA using the iScript first strand cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Primers to amplify the two A. mellifera dnmt1 paralogs, dnmt1a and dnmt1b, were taken from Wang et al. [5]. The AmDnmt1b primers did not amplify our cDNA, so we used only the AmDnmt1a primers; AmDnmt1a has been shown to be catalytically active [5]. We used A. mellifera dnmt1a (NCBI Genbank

NM_001171051.1) and dnmt3 (NC_007071.3) gene sequences as BLAST queries to find orthologous sequences in B. terrestris and Lasius spp. Sequence for primer design was downloaded from Genbank for Bombus (NT_177367.1), while for

Lasius we used transcriptome sequence data from Lasius neglectus (C. Morandin

& A. Mikheyev, unpublished). Primers for amplifying dnmt3 from A. mellifera were designed using A. mellifera dnmt3 gene sequence (NC_007071.3); other primers were designed after using BLAST to find orthologous dnmt3 sequence from data on Genbank for B. terrestris (NC_015763.1), and from the L. neglectus transcriptome data for Lasius spp.

We chose RPL32 as a control gene because it shows stable expression between the female castes in bees and ants [6,7]. RPL32 primers were designed for A.

mellifera and B. terrestris using Genbank sequences NM_00101158 and

XM_003398930.1, respectively. For Lasius species, RPL32 primers were designed after searching the L. neglectus trascriptome with BLASTN using Camponotus

floridanus RPL32 (XM_011257027.1) as the query. We verified that RPL32 expression did not differ significantly between the control and queenpheromone treated groups of workers within each species (Figure S2).

Where possible, primer pairs were designed with one primer overlapping an exon boundary, preventing amplification of any genomic DNA that might have contaminated the RNA extractions. Where alternative splicing was evident, we designed primers that spanned the boundaries of exons present in all known splice variants. Primer pairs were controlled for amplification specificity, primer dimer amplification, and DNA amplification before use. See Table S3 for primer sequences.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) amplifications to determine expression levels were conducted on a CFX384 cycler using IQ SYBR Green reaction mix

(BioRad), with a three-step cycling protocol and annealing temperature of 55 o C in all reactions. The control and pheromone-treated samples of each species were always run on the same PCR plate to prevent any confounding batch effects. Each individual was run in triplicate for each primer set, for technical replication. Due to occasional amplification failures, the mean number of technical replicates was 2.75 ± 0.006. All experimental procedures, including insect handling, pheromone application, laboratory work and data analysis, were performed blind to mitigate observer bias [8].

Statistical analysis

We first tested whether the ~3 technical replicates of each individual/primer combination gave comparable results. The repeatability (calculated following

[9]) was high (r = 0.995), so we took the geometric mean of the technical replicates in all subsequent analyses.

To control for differences in the amount of cDNA between wells, we subtracted the Cq value of the reference gene RPL32 from the Cq value for the target gene for each sample, giving a value termed ΔCq. We next subtracted the mean ΔCq value for dnmt1 in the control group for the focal species ( ΔCq 𝑑𝑛𝑚𝑡1

) from the

ΔCq value of individual i and gene j, giving ΔΔCq ij

= ΔCq

ij

– ΔCq 𝑑𝑛𝑚𝑡1

. Finally, we calculated the relative level of gene expression as g = log

10

(2 -ΔΔCq ). Positive values of g indicate that the expression of the target gene is higher than the mean

dnmt1 expression in the control group, while negative g means expression is lower than that.

We analyzed g with mixed effects models with colony as a random factor, using the lmer function in the lme4 package for R, coupled with the lmerTest package to estimate p-values. To control the false discovery rate during separate testing of each combination of gene and species, we adjusted the p-values in Table 1 following Benjamini & Hochberg [10]. In initial analyses we also fit the colony × treatment interaction as a random effect to allow for differences in the response to treatment between colonies. However, the effect of this predictor was extremely low (indicating that colonies responded similarly to treatment), and so we removed it to improve model convergence.

Supplementary references

1. Holman, L., Jørgensen, C. G., Nielsen, J. & d'Ettorre, P. 2010 Identification of an ant queen pheromone regulating worker sterility. Proc. Roy. Soc. B 277,

3793–3800.

2. Holman, L., Lanfear, R. & d'Ettorre, P. 2013 The evolution of queen pheromones in the ant genus Lasius. J. Evol. Biol. 17, 1549–1558.

3. Grozinger, C. M., Sharabash, N. M., Whitfield, C. W. & Robinson, G. E. 2003

Pheromone-mediated gene expression in the honey bee brain. PNAS 100,

14519–14525.

4. Holman, L. 2014 Bumblebee size polymorphism and worker response to queen pheromone. PeerJ 2, e604.

5. Wang, Y., Jorda, M., Jones, P. L., Maleszka, R., Ling, X., Robertson, H. M.,

Mizzen, C. A., Peinado, M. A. & Robinson, G. E. 2006 Functional CpG methylation system in a social insect. Science 314, 645–647.

6. Corona, M., Hughes, K. A., Weaver, D. B. & Robinson, G. E. 2005 Gene expression patterns associated with queen honey bee longevity. Mech. Age.

Devel. 126, 1230–1238.

7. Morandin, C., Dhaygude, K., Paviala, J., Trontti, K., Wheat, C. & Helanterä, H.

2015 Caste-biases in gene expression are specific to developmental stage in the ant Formica exsecta. J. Evol. Biol. 28, 1705–1718.

8. Holman, L., Head, M. L., Lanfear, R. & Jennions, M. D. 2015 Evidence of experimental bias in the life sciences: why we need blind data recording.

PloS Biol. 13, e1002190.

9. Lessells, C. M. & Boag, P. T. 1987 Unrepeatable repeatabilities: A common mistake. Auk 104, 116–121.

10. Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. 1995 Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Statist. Soc. B

57, 289–300.

Species

A. mellifera

B. terrestris

L. flavus

L. niger

Supplementary tables

Table S1: Sample sizes for each experimental unit (number of individual insects).

Treatment Colony Sample size

Control

Queen pheromone

Control

Queen pheromone

Control

Queen pheromone

Control

Queen pheromone

Am 1

Am 2

Am 3

Am 1

Am 2

Am 3

Bt 9

Bt 10

Lf 1

Lf 2

Lf 3

Lf 4

Lf 5

Lf 6

Lf 7

Lf 8

Bt 1

Bt 2

Bt 3

Bt 4

Bt 5

Bt 6

Bt 7

Bt 8

Ln 1

Ln 2

Ln 3

Ln 4

Ln 5

Ln 6

Ln 7

Ln 8

Lf 1

Lf 2

Lf 3

Lf 4

Lf 5

Lf 6

Lf 7

Lf 8

Ln 1

Ln 2

Ln 3

Ln 4

Ln 5

Ln 6

Ln 7

Ln 8

8

6

5

5

15

10

7

7

6

7

15

10

10

15

10

9

10

15

12

14

15

15

15

15

15

15

17

16

16

15

15

15

5

6

5

5

9

7

5

13

15

16

16

11

17

16

15

19

Table S2: Effects of queen pheromone (QP) treatment on gene expression. The

ΔΔCq columns show the mean ΔCq value, minus the mean ΔCq value for dnmt1 in the control group for that species (standard error in parentheses). Lower ΔΔCq values indicate higher expression. The “Fold difference” column gives the difference in gene expression between the QP-treated individuals and the controls as a fold difference (i.e. 0.5 is halving, 1 is no change, 2 is doubling), calculated as 2^(-1 × (ΔΔCq

QP

– ΔΔCq

Control

)). The associated 95% confidence intervals were calculated by bootstrap resampling with 10 5 replicates. The t, p and colony effect columns are from eight linear mixed models of g with treatment as a fixed factor and colony as a random factor; ‘Colony effect’ is the proportion of variance in g explained by colony. The p-values have received

Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

Species Gene

A. mellifera dnmt1a 0 (0.41) 1.54 (0.25) 0.34 (0.18 - 0.64) -3.48 0.0008 0.15 dnmt3 -2.63 (0.31) -1.36 (0.27) 0.42 (0.25 - 0.74) -3.79 0.0006 0.35

B. terrestris dnmt1 0 (0.20) 0.25 (0.18) 0.84 (0.58 - 1.23) -0.66 0.53 dnmt3 -0.87 (0.07) -0.68 (0.09) 0.88 (0.75 - 1.02) -0.70 0.53

L. niger

L. flavus

0.16

0.10 dnmt1 0 (0.05) -0.30 (0.04) 1.23 (1.14 - 1.35) 4.56 0.0001 0.016 dnmt3 2.30 (0.05) 1.97 (0.05) 1.26 (1.14 - 1.40) 4.49 0.0001 <0.001 dnmt1 0 (0.05) -0.38 (0.08) 1.30 (1.14 - 1.49) 3.84 0.0004 0.015 dnmt3

Mean (SE) ΔΔCq

Control

2.37 (0.06)

QP-treated

2.15 (0.07)

Fold difference

(95% CI) t

1.16 (1.01 - 1.32) 2.42 p

0.017

Colony effect

0.036

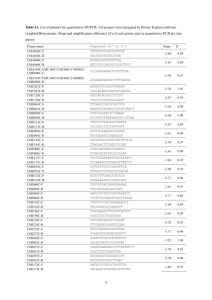

Table S3: Forward and reverse primer sequences designed for this study.

Species Gene Forward primer

B. terrestris dnmt3 CTCCAAGCCTCCAAGGATTATT

Lasius spp. dnmt3 CTGCATTCGAGAGCTTGGAT

Reverse primer

A. mellifera RPL32 AAGTTCATTCGTCACCAGAG

B. terrestris RPL32 TTAGACGACCGTGATCCAAG

CTTCCAGTTCCTGTACATTATG

GTTTACGCCAGTTTCTCTTCA

Lasius spp. RPL32 GATATGACAAACTTAAGCGCAA ATCGAAAGCTGTTGAGCACG

B. terrestris dnmt1 ATTGGAGCGATGAAGTTTGTAA CACACCCAGCAAATACATCC

Lasius spp. dnmt1 CCTAAGAGACAACGATGTGGTG ATCAGAATCATCTGCTTCCTGGA

A. mellifera dnmt3 GAAGCTCGTATATCATTATTGAAC CAACATCTGCATAGTTGCGTC

GTCTTACCCTCAGCAACTCG

CAGGCTATCACACCAGGATT

Supplementary figures

Figure S1: The same data as in Figure 1, sub-divided by colony. The figure shows expression of dnmt1 (left column) and dnmt3 (right column) relative to the mean expression level of dnmt1 in the control group for the focal species (g). Positive values of g indicate higher expression than this reference point, and negative values indicate lower expression. The boxes show the median and interquartile range (IQR), and the whiskers show the farthest points that are within 1.5×IQR of the bounds of the IQR.

Figure S2: The distribution of Cq values for the reference gene RPL32 in each combination of species and treatment. Higher Cq values indicate lower expression of RPL32. There was no significant difference in RPL32 expression between treatments within the four species. The associated p-values are from four separate linear models testing the effects of treatment on the Cq value for

RPL32, and have been subjected to Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing. The boxes show the median and interquartile range (IQR), and the whiskers show the farthest points that are within 1.5×IQR of the bounds of the

IQR.