Course literature - Designfakulteten

advertisement

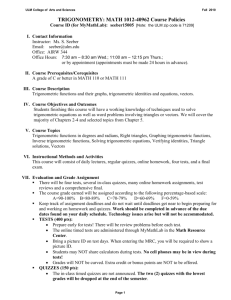

Umeå Institute of Design Umeå University, SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden Phone: +46 90 786 5000 www.uid.umu.se Course syllabus - draft Ref. no. Date March 18, 2015 Page 1 (5) Design Histories Credit points: 7,5 ECTS Course code: Responsible department: Umeå Institute of Design Main field of study: Industrial Design Level: PhD Specialisation in relation to degree requirements: Doctoral degree in Industrial Design Subject area: design history Grading scale: Pass / Fail Any programme affiliation: Confirmation: This is a draft, the syllabus has not yet been approved by the Research Council at Umeå Institute of Design. Details, including the literature, may change. Contents The course will be about the history – or better: histories – of design and design research. More specifically, it will be about how industrial design has articulated, related to and reflected upon its past, present and future. As such it is less oriented towards the historical narratives that have evolved largely under the umbrella of art history, and more attuned towards historical examples of how industrial design itself has articulated its project, its purpose, privileges and positions. The purpose of the course is thus not to give us a comprehensive overview of all design history relevant to industrial design, but rather to inquiry into some examples that seem to have a certain bearing on our current design practices and forms of research. Most texts will be historical in the sense that they are now part of our history, not in the sense that they address historical matters. Indeed, much of the literature are calls for change, manifestos, etc., thus representing historical projections into what then seemed to be the future. Looking into the evolution of industrial design, we will try to understand the historical context of practices still present in educational environments such as Umeå Institute of Design. In particular, this involves asking questions about the relations between developments in design and the changing conditions and needs of society and industry. However, since the orientation of the course is around unpacking notions that seem to have had a significant impact on current practices in places like UID, many of the examples will stem from American, British, German and Nordic perspectives. In a sense, to be able to discuss the implications of having a narrow view, we must also see what this narrow view actually looks like. The course will consist of 5 seminar sessions, each based around a theme. The format will be discussions around texts we read. Each session will be over two days, starting at 10 the first day and ending around lunch the day after. We will have two sessions this spring, April 21-22 and May 26-27. The third session, hopefully a mini symposium with invited guests, will be late September/early October. The last two sessions will follow later in the fall. Page 2 (5) The first session will be about what design history is, or could be, and why it matters. In a sense, it will be about the problem of articulating a design history in the light of significant disagreement about both what design is, and what is interesting and important about its history. In the second session we will take a walk through history. Starting with how industrialisation challenged previous conceptions of aesthetics and ethics, art and technology, we then turn to the formation of the Bauhaus and later HfG Ulm. As we enter the 1960’s and 70’s our focus will be on how industrial design begun to expand in new dimensions (as in the turn towards systems and ecologies, or towards design purpose beyond –or indeed critiquing– utility). The third session will be about the Nordic context, and the current plan is to try to make this into a mini symposium with invited guests. The fourth session will be based on presentations by the students: each participant will select a piece of design history (a text, an exhibition, a film, etc.) present it and discuss how her/his own work builds on or relates to it. The fifth session will conclude the course, but it also still open for things we during the course discover we need to look further into, things we might need to add, etc. There will be two deliverables in the course besides active participation in all seminars: - An oral seminar presentation based on historical text/exhibition/etc. and its use in/relation to the student’s own work (fourth session) - An expansion and deepening of the oral presentation (and the discussion that followed) in the form of a written essay. Expected learning outcomes A deepened understanding of the history of design and design research. An ability to locate, articulate and critique issues pertaining to historical and contemporary design research and design practice, including to critically examine one’s own research and practice in its historical contexts. An ability to articulate and make use of design research methodology related to historical studies and the humanities. Relation to general study plan Courses in this thematic area should address the following learning goals in the general study plan: Primary: 1.1.1, 1.1.2, 2.1.1, 2.1.2, 2.2.1, 2.2.3, 2.3.1 Secondary: 1.2.1, 1.2.2, 1.2.5, 1.3.1, 1.3.2, 2.2.2, Required knowledge Qualifications for admission to the PhD programme in industrial design, or equivalent. Page 3 (5) Form of instruction Lectures, seminars and workshops. Examination modes Examination is held both orally and in writing, individually and in group. The assessment of the course is based upon active seminar participation, an individual oral presentation in seminar form, and one individual written essay (as instructed during the course). Grades on the course are awarded when students have passed all examinations and compulsory course elements. After completing the course, one of the grades Fail (U) or Pass (G) is awarded the student. A student who for two consecutive examinations for the same course has not been passed, has the right to have another examiner appointed, if there are no special reasons against this (Higher Education Ordinance chapter 6, 22 §). The request for a new examiner shall be made in writing to the Research Council of Umeå Institute of Design. Academic credit transfer Equivalency credits for this course can only be given if it can be shown through transcripts and course plans that a similar course has been passed and after the supervisor and examiner for the PhD education have evaluated and approved the students’ individual level of skills and knowledge. Course literature Note: this is not a basic course in design history. Please pick up a suitable textbook on the subject in case your design history needs a bit of a refresh. There are many books that can do the job, but in case you want a suggestion this could be one: Woodham, J.M. (1997). Twentieth century design. Oxford: Oxford University Press. I. What and why design histories? [April 21-22] Dilnot, C. (2015). History, design, futures: contending with what we have made. In Fry, T., Dilnot, C.& Stewart, S.C. (2015). Design and the question of history. London: Bloomsbury. Pevsner, N. (1936, 1949). The Modern movement before nineteen-fourteen, excerpt from Pioneers of Modern Design. In Lees-Maffei, G. & Houze, R. (Eds.) (2010). The design history reader. London: Bloomsbury. Margolin, V. (1995). Design History or Design Studies: Subject Matter and Methods. Design Issues, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring, 1995), pp. 4-15. Including (from the same issue): Forty, A. Debate: A Reply to Victor Margolin, pp. 16-18. Margolin, V. A Reply to Adrian Forty, pp. 19-21 Woodham, J. M. (1995). Resisting Colonization: Design History Has Its Own Identity. Design Issues, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring, 1995), pp. 22-37. Buckley, C. (1986). Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design. Design Issues, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Autumn, 1986), pp. 3-14. Page 4 (5) Attfield, J. (1989). FORM/female FOLLOWS FUNCTION/male: Feminist Critiques of design. In LeesMaffei, G. & Houze, R. (Eds.) (2010). The design history reader. London: Bloomsbury. Sparke, P. (1995). As long as its pink: the sexual politics of taste (introduction). In Lees-Maffei, G. & Houze, R. (Eds.) (2010). The design history reader. London: Bloomsbury. II. Design histories [May 26-27] i) Industrial beginnings Semper, G. (1852). Science, industry, and art. In Lees-Maffei, G. & Houze, R. (Eds.) (2010). The design history reader. London: Bloomsbury. Morris, W. (1884). Useful work versus useless toil. In Kolocotroni, V., Goldman, J. & Taxidou, O. (Eds.) (1998). Modernism: an anthology of sources and documents, pp. 27-31. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press Lloyd Wright, F. (1901). The Art and craft of the machine. In Lees-Maffei, G. & Houze, R. (Eds.) (2010). The design history reader. London: Bloomsbury. Loos, A. (1908). Ornament and Crime. In Lees-Maffei, G. & Houze, R. (Eds.) (2010). The design history reader. London: Bloomsbury. ii) Bauhaus Gropius, W. (1919). Manifesto of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar. For example in: Conrads, U. (Ed.) (1964). Programs and manifestoes on 20th-century architecture, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA pp. 49-53, or http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/das-bauhaus/idee/manifest Gropius, W. (1926). Bauhaus Dessau – Principles of Bauhaus production. For example in: Conrads, U. (Ed.) (1964). Programs and manifestoes on 20th-century architecture, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA pp. 95-97. Fleishmann, A. (1924). Economic living. In Kolocotroni, V., Goldman, J. & Taxidou, O. (Eds.) (1998). Modernism: an anthology of sources and documents, p. 302. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press Albers, A. (1968). Oral history interview with Anni Albers, 1968 July 5, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Available at: http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-historyinterview-anni-albers-12134 iii) HfG Ulm Maldonado, T. (1958). New Developments in Industry and the Training of the Designer. In Ulm 2, Quarterly bulletin for the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, October 1958. Page 5 (5) Maldonado,T.and Gui, B. (1964). Science and Design. In Ulm 10/11, Quarterly bulletin for the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, May 1964. Maldonado, T. (1991). Looking back at Ulm. In Lindinger, H. (Ed.). Ulm design: the morality of objects: Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm 1953-1968. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press Rittel, H.W.J. (1991). The HfG legacy? In Lindinger, H. (Ed.). Ulm design: the morality of objects : Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm 1953-1968. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press iv) Expanding design I Jones, J.C. (1970/1992). Design methods, chapters 2 and 3. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Papanek, Victor (1977). Design for the real world: human ecology and social change, Chapters 2-4. St Albans: Paladin v) Expanding design II Branzi, A. (1988). Those monks on the hill. In Branzi, A. Learning from Milan: Design and the second modernity. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Branzi, A. (2001). A Homeless Country: Experimental models for the domestic space. In Bosoni, G. (Ed.) Italy; Contemporary Domestic Landscapes 1945-2000. Milan: Skira. Thackara, J. (1988). Beyond the object in design. In Thackara, J. (Ed.). Design after modernism: beyond the object. London: Thames and Hudson Foster, H. (2002). Design and Crime (chapter). In Foster, H. Design and Crime. London: Verso. III. Scandivanian stories Fallan, K. (Ed.) (2012). Scandinavian design: alternative histories. London: Berg Additional literature will be added depending on the format and content of the session (the ambition is to make a small symposium with invited guests on this theme) IV. Your stories Each course participant selects a piece of design history, presents it and its relation to her/his own work. V. Final