Yury Zaretskiy Two Reflections on Aron Gurevich`s Legacy Thinking

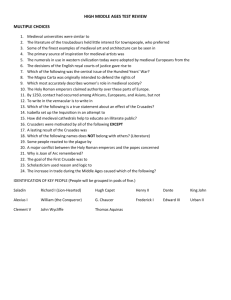

advertisement

Yury Zaretskiy Two Reflections on Aron Gurevich’s Legacy Thinking about Aron Gurevich’s legacy I usually focus on two subjects. First, I ask myself a question: how it was possible for this person to produce such groundbreaking pieces of historical scholarship living in the Soviet Union and being a part of Soviet academia? Second, I reflect on some striking parallels between Gurevich’s life experience and historical topics he explored in his writings. *** The first subject obviously needs a special inquiry, so at present I can only offer a few preliminary remarks and suggestions. In my view the miracle of appearance of Categories of Medieval Culture, Medieval Popular Culture, Historical Anthropology of the Middle Ages1 and other Gurevich’s books and articles in the Soviet Union became possible because of fortunate coincidence of two groups of factors: “inner” and “outer”. By inner factors I mean some personal characteristics of the historian. In the first place these are: his discontent with the practice of history writing strictly controlled by Marxist ideology, his openness to novelties, his stubborn persistence in reaching his scholarly goals, his prudence in social behavior, and finally, his firm confidence in the scholarly significance of his work. As for outer factors, I would first mention the shift in the Soviet humanities to culture studies associated with Khrushchev’s “Thaw” in late 1950s – 1960s. At that time studies of “world culture” gained official recognition. This resulted in establishment of the Scientific Council on the History of World Culture at the Soviet Academy of Sciences and of the journal Herald of the World Culture. But may be the most significant indicator of this shift was the formation of a small group of scholars on the periphery of official academia who practiced new theoretical approaches to the study of the past. For instance, in the 1960s several scholars united under the leadership of Yuri Lotman to form what would become known as Moscow-Tartu school of semiotics; pioneering studies of historical poetics, comparative literature and myth were launched; and Mikhail Bakhtin’s immensely influential book on Rabelais was published after years of oblivion.2 As Aron Gurevich noted later in his autobiography, these works strongly influenced the emergence of his own approach to history. 1 Aron Gurevich, Categories of Medieval Culture, G.L. Cambell, trans. (London, 1985); Aron Gurevich, Medieval Popular Culture: Problems of Belief and Perception, J.M. Bak & Paul A. Hollingsworth, trans. (Cambridge, 1990); Aron Gurevich, Historical Anthropology of the Middle Ages, J. Howlett, ed. (Chicago, 1992). 2 Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Helene Iswolsky (Bloomington, 1984). 1 *** Now a few words about parallels between Gurevich’s life experience and historical topics he explored. His study of the medieval individual will be taken as an example here. Gurevich’s persistent attention to “personality” as the central category of medieval culture is closely related to the concrete circumstances of his life and work. His disapproval of official Soviet ideology, his decades-long forced isolation from the international scholarly community and his lack of recognition in his home country led to his focus on the inner personal world of a “medieval man.” Tight connection between the historian’s life and work are pretty well documented by Gurevich’s own revelations in his last works. In The Origins of European Individualism he states that the book was due first and foremost to the author’s reflections about the country in which he lived: This book is the work of a Russian historian, and I must confess that the subject of the individual and individuality is now coming into its own unprecedented force in my country… Russia cannot be drawn into European civilization… without adopting certain values fundamental to that civilization.3 And in the expanded Russian version of the same book he emphasizes that his studies of medieval personality were closely interconnected with his thoughts on his own life: At certain stage of my work on the medieval individual I felt the need to write about myself. I tried to look at my own development as a historian…At this point I realized that the subject of the book emerged not only because of my interest for medieval culture…but also as a result of my reflections on myself.4 *** And a final remark. Maybe it is too biased, but I cannot resist from sharing it in this audience. While reading Aron Gurevich’s autobiography, I was amazed with its striking parallels to Peter Abelard’s Historia calamitatum. The Russian historian speaks about his misfortunes in a manner very similar to that of the French medieval philosopher (this is especially clearly seen when Gurevich refers to fights with his opponents). And from his autobiography also comes out that he is a winner, that his fame will live by far more than the names of his enemies. 3 4 Gurevich, OEI, p. 4. Gurevich, Individual and Society in the Medieval West, 372. 2