Look at us! A Primary Years` investigation into Adelaide`s biodiversity

advertisement

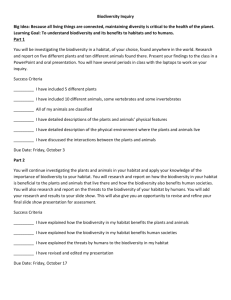

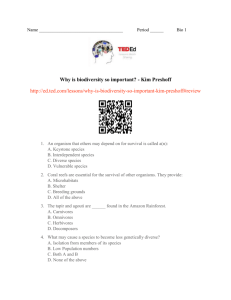

1. Improving biodiversity Look at us! A Primary Years’ investigation into Adelaide’s biodiversity: past, present and future. Contents Big ideas Page 1 Essential questions Page 1 Links to the SA Teaching for Effective Learning framework Page 1 Links to the Australian Curriculum Page 1 Key Words Page 2 Learning activities Page 2 Activity 1: How has the Adelaide environment changed since European settlement? Page 2 Activity 2: How much have Adelaide’s landscapes and vegetation changed and how have these changes impacted on animals? Page 3 Activity 3: What is biodiversity and why is it important? Page 3 Activity 4: How we can improve biodiversity? Page 3 Activity 5: Taking action Page 4 Extension activities Page 4 Resources Page 4 Attachment one: Readings Page 5 Attachment two: Assessing biodiversity group worksheets Page 8 Big ideas The South Australian landscape and vegetation profile changed significantly as a result of land clearance and land uses. As a result plants, animals, and the ecosystems they live in (i.e. biodiversity) are under increasing pressure. By examining the past and the present day vegetation profiles, through art and literacy, students come to understand the importance of biodiversity. They undertake a plant and habitat assessment of the school grounds and decide how to take action to improve its biodiversity. Teachers are encouraged to adapt the unit of work to suit the interests and needs of their students. Essential questions 1. 2. 3. 4. How has the Adelaide environment changed since European settlement? Why is biodiversity important? What is the condition of the biodiversity in our school grounds? How can we improve the biodiversity in our school grounds? Links to the SA Teaching for Effective Learning framework - Domain 4 Personalise and connect learning 4.1 build on learners’ understandings 4.2 connect learning to students’ lives and aspirations 4.3 apply and assess learning in authentic contexts 4.4 communicate learning in multiple modes Links to the Australian Curriculum - (teachers to determine specific links for year levels) Learning Areas History Geography English The arts Science 2. Cross-curriculum priorities Sustainability Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures OI2. All life forms, including human life, are connected through ecosystems on which they depend for their wellbeing and survival. OI7. Actions for a more sustainable future reflect values of care, respect and responsibility, and require us to explore and understand environments. OI.3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples have unique belief systems and are spiritually connected to the land, sea, sky and waterways. OI5. World views are formed by experiences at personal, local, national and global levels, and are linked to individual and community actions for sustainability. OI9. Sustainable futures result from actions designed to preserve and/or restore the quality and uniqueness of environments. General capabilities Literacy Numeracy Information and communication technology (ICT) capability Critical and creative thinking Personal and social capability Ethical understandi ng Intercultural understandin g Key Words Key word Bio-indicator Biodiversity Diversity Habitat Ecosystem Habitat diversity Habitat condition Aquatic macroinvertebr ates Use Biological indicators are animals, plants and other life-forms used to monitor the health of an environment or eco-system. If an animal is an indicator, it is the first to respond to change; e.g. frogs indicate the health, or otherwise, of a waterway, as they are one of the first species to be impacted by pollution. All living organisms (trees, plants, genes, ecosystems). The number of different types (e.g. types of water macroinvertebrates) not the total number of individuals. A habitat is an area where a species lives and gets everything it needs; e.g. a pond is an ideal habitat for frogs. An ecosystem can consist of multiple habitats. A forest ecosystem may have a pond (for frogs), large trees (for nesting birds), and logs (for lizards). The number of different types of different habitats in an ecosystem. The overall health of a particular habitat for a certain species. Aquatic = lives in water. Macro = can be seen with the human eye. Invertebrates = animals without a backbone. Assessment tasks Teachers are encouraged to design assessment tasks to suit their student learning needs, year level, and the achievement standards in the Australian Curriculum Learning activities Activity 1: How has the Adelaide environment changed since European settlement? Materials: • • Art materials Map of the school grounds • Download images of colonial and contemporary Adelaide using Google, to be displayed on the Smart Board. Take note of copyright restrictions. Colonial examples include: - The City of Adelaide from Mr Wilson's Section on the Torrens, June 1845 painted by George French Angas 3. - Government House on North Terrace, Adelaide in 1845, painted by Samuel Thomas Gill - North Terrace, view taken looking east s east painted by Martha Berkeley. • Images of colonial and present day Adelaide from different perspectives (e.g. Torrens, Glenelg, Adelaide city). Take note of copyright restrictions. Duration: 1 hour Begin by asking students how much they think Adelaide has changed since European Settlement. Ask them to share their thoughts on how the vegetation and people have changed. In groups, using computers, compare and contrast images of colonial Adelaide with present day Adelaide. Ask students to look at similarities and differences. After some discussion bring students back and encourage them to share their finding and thoughts. Ask students to go to various areas of the school grounds and sketch the landscape and plants. When they return ask them to talk about their sketches in groups highlighting what they discovered. Display the sketches around the map of the school grounds with a connecting link between the sketch and the relevant area. Activity 2: How much have Adelaide’s landscapes and vegetation changed and how have these changes impacted on animals? Materials: Reading sheets 1-4 (Attachment one). Map of Adelaide. Duration: 20-30 minutes Ask students if they think the vegetation has changed throughout Adelaide and how and why they think it has changed. If students say it has changed due to clearance ask them if there is anything else that has changed (this may start a conversation on animal loss, weeds or fire). Divide the class into groups of about five students and give each group one of the Reading sheets. Ask them to skim and scan the text and look up any words they are unsure of in a dictionary. Then they take turns reading the sheet and finding any mentioned areas of Adelaide on a map and write the kind of vegetation on the area. Ask them to discuss the evident differences in the landscape, vegetation and animals from then to now. Bring the four groups back together to summarise and compare their discussions. The key idea to reinforce is land clearing for housing, roads, other structures and farming has reduced the vegetation and therefore the habitat, leading to extinctions for some and serious problems for other wildlife. Note: as the fact sheet texts were written a long time ago the style of language and vocabulary can be quite challenging. Instead of the group activity, you may wish to choose one to read to the class and then discuss. Activity 3: What is biodiversity and why is it important? Materials: Video on Biodiversity – Click here Duration: 20-30 minutes Ask students what the term biodiversity means. Once you have determined as a class that it is the diversity of all life, ask students why it is important. Following some discussion have a look at the video and confirm and/or extend their thinking about biodiversity. Ask them how they think biodiversity has changed since European Settlement. Some key discussion points may go beyond South Australia such as palm oil, clearing of rainforests, extinction of iconic animals such as the Tasmanian Tiger or those nearing extinction such as gorillas and tigers (some subspecies of tiger are already extinct). You can bring back the discussion to a local level by talking about some of our local threatened species such as the Yellowtailed Black Cockatoo or the Southern Brown Bandicoot. The key ideas to reinforce are that loss of vegetation = loss of habitat = a loss of biodiversity and that the loss of biodiversity impacts on humans, other animals and the planet, and it is up to us to improve biodiversity. Activity 4: How we can improve biodiversity? 4. Materials: A3 copies of an aerial map of the school, an original vegetation map of South Australia or use the Backyards for Wildlife Interactive map. Copy the Assessing biodiversity worksheets (Attachment two) for each group. Duration: 1 – 1.5 hours (depending on level of engagement) Using the aerial map or the Backyards for Wildlife Interactive map here, locate the area the school is in and identify the original dominant vegetation. Compare it with the vegetation on the aerial map of the school. Identify the similarities and differences. Hypothesise about the health or otherwise of the biodiversity in the school grounds. Explain to students that there is a way to now test the hypothesis and see how healthy the biodiversity of the school grounds really is. The biodiversity assessment Group 1 - Task 1: investigating trees and Task 2: investigating canopy cover Group 2 - investigating understorey Group 3 - Task 1: - investigating organic litter and Task 2: investigating logs and rocks Group 4: - investigating weediness The assessment process The investigation tasks can be undertaken at the same time by groups of students. It is recommended to have an adult with each group to support the process. Students provide an assessment of the quality of factors of habitat and biodiversity in the school grounds. Ideally, the activities will be undertaken annually (or seasonally) to provide snapshots of the state of biodiversity over time. Before starting the activities it is recommended to go through them with students. The background notes will support their understanding of what they are looking for. After their investigation in the school grounds, each group prepares a report on their results, including the nature of the investigation, the results (including a graph; e.g. bar graph, pictograph) and their opinion of the accuracy of the original hypothesis. Each group presents their findings to the class and discusses their original thoughts and recommendations. Collate the results and decide on the condition of biodiversity in the school grounds. Activity 5: Taking action Materials: results of biodiversity mapping from Activity 4. Duration: 30-40 minutes After looking at the results of the survey, and reminding them of the importance of biodiversity, ask students for ways to improve the biodiversity of our school grounds into the future. Using the information collected through the assessment activity decide on priority areas for development in the next 12 months. Prepare persuasive arguments to get staff and other students involved in your plans. Give preference to local provenance plants to return the vegetation (as close as possible) to its original state. Document plans in a SEMP (School Environment Management Plan). Undertake, monitor (e.g. using photo points) and evaluate actions. Record the types of wildlife that comes to visit your improved patch. Your local NRM Education Officer (www.nrmeducation.net.au/index.php?page=contact-us) can provide advice and support. Extension activities • • • • Research Adelaide’s Aboriginal groups and their dreaming stories that relate to animals and the land. Present the stories in a multimodal format to share with other classes. Ask students to choose a plant in the yard and to research what it is, either in a plant book or on the internet. Once they have found out if it is native or feral ask them to write a report for the grounds person recommending either the care or removal of the plant. Research the history of the local area and identify some significant natural landmarks. Research important names in Adelaide’s history, such as: Colonel William Light (including parklands in city design), Governor John Hindmarsh, G.F. Angas, Hans Heysen, John Glover. Find out who they were, what they achieved and what has been named in their memory. 5. • • Students find out more about urban planning that includes green spaces (e.g. Beyond, Aldinga Eco-village and Christie Walk). Ask them to design their own eco-village based on what they find out. Ask students to consider their learning about biodiversity and list some biodiversity improvements they can make to their backyard. Resources • • • NRM Education resources on biodiversity – click here to view the resource Weeds - click here to view the resource (includes a weed identification tool) Primary Connections: Year 3, Feathers, fur or leaves?; Year 4, Friends or foe?; Year 5, Desert survivors; Year 6, Marvellous micro-organisms. 6. Attachment one: Readings Reading 1 The hidden nature of Adelaide extract from the introduction to The Native Plants of Adelaide by Phil Bagust and Linda ToutSmith, 2010 (reproduced with the kind permission of The Wakefield Press). “Quickly, think of the house or unit in which you live. Now try to imagine the landscape that existed before the Europeans built on it. What did the landscape look like? Was it farming land? And before it was farmed? Was it forest? Grassland? Wetland? … For a start the Adelaide Plains are, by definition, quite flat. They are also rather fertile, and mostly have deep and arable soils. We have a delightful Mediterranean climate. This made the Adelaide Plains extremely attractive to the first settlers as farming land. Another reason is that much of the Adelaide Plains was already quite open prior to settlement, having a kind of parkland appearance with large but scattered trees, a state at least partly attributable to the burning practices of the original Kaurna inhabitants. This open appearance, so attractive to the European eye, made further clearance much easier. So the answer to our original question is that your dwelling was probably built on arable land that had already been farmed for many years. It is no wonder that most Adelaide inhabitants have little idea of what the pre-European vegetation looked like, because over vast swathes of suburbia, unless one knows exactly where to look, it is basically all gone and has been for over a hundred years. Add to this the interest in recent decades in planting Australian natives that may have been sourced from other regions over a thousand kilometres away and there is little wonder that confusion exists about the identity of the truly indigenous plants of the Adelaide Plains. … The picture that emerges is one of a complex and diverse mosaic of woodlands, with different tree species dominating in various areas. Along the many streams, but stretching out over the eastern Adelaide Plains, huge River Red Gums and Blue Gums, some of which still exist, would have dominated a rich grassy woodland. To the west behind the coastal dunes, stately Native Cypress-pines and Sheoaks dominated. Photo: J. Gramp. Horsnell Gully South of the Torrens the dark-barked Eucalypt the settlers called ‘peppermint’ and which is now known as the Grey Box gave the early name to the present-day suburb of Black Forest, while on the drier northern Adelaide Plains the closely related but smaller Mallee Box predominated. Where the soils were sandier and less fertile, such as in parts of the north-eastern suburbs and on the coastal cliffs south of Marino, a dense heathland of colourful shrubs and sedges developed, while along the beaches, a near continual sweep of coastal shrubland clothed the white dunes. If there is one thing that would surprise a contemporary Adelaidean magically transported back to 1836 it would probably be how wet much of the Adelaide Plains area, particularly the area south of the Torrens River, really was. The many small creeks now confined within concrete drains once overflowed each winter to gently cover and irrigate the Adelaide Plains, and our larger streams discharged into a vast wetland of rushes, reeds and sedges behind the coastal dunes between Brighton and Port Adelaide. This western coastal area, which must have been a wildlife wonderland, has now been almost obliterated. This fantastic variety of environments, amongst the most diverse on South Australia, supported a population of native mammals, birds and reptiles that would amaze the present-day Adelaideans. Emus, goannas, quolls, bandicoots, platypuses, bettongs, wombats, and even that Australian icon of rarity, the bilby, were plentiful on the Adelaide Plains prior to European settlement. It would surprise few to learn that in almost no area of the Adelaide Plains are naturally occurring, local native plants still common. Over ninety percent of the original vegetation has been destroyed, and if one removes the large, relatively intact mangrove area of the Port River estuary, that remnant fraction falls to a few percent at most.” 7. Reading 2 Adelaide in 1839 from the South Australian Register 15 January 1878 (reproduced with the kind permission of The Wakefield Press). “You feel you have done something heroic in leaving a civilised land to come to where swans are black instead of white. Where indigenous quadrupeds travel in leaps, erect on their hind legs, instead of walking or running on all four. Where trees shed their bark instead of their leaves, and rivers flow sometimes underground, sometimes on the surface, and instead of broadening as they near the ocean, narrow to a trickle or disappear completely as they approach it. Where the aboriginal population, instead of sporting the orthodox white and red, have skins the colour of the finest quality ebony. Though the road from Glenelg to the site of Adelaide was little more than a tortuous, winding track created by the footsteps of numerous earlier pedestrians and the few haulage animals and vehicles that serviced the town, I enjoyed the experience of my first walk in the new colony. Photo: J. Gramp. Musk Lorikeets The narrow track meandered along amid an apparently boundless maze of strongly scented shrubs and magnificent gum trees. The branches of the trees were crowded and enlivened by flocks of parrots, cockatoos and parroquets, whose coloured and varied plumage rendered the scene immensely picturesque. As yet the multitude of white, blue and yellow flowers, which I was to behold on this very same spot a few months later, were cradled and temporarily hidden beneath the bare and apparently sterile surface of the earth. Flocks of screaming, chattering birds frolicked like feathered monkeys and accompanied every traveller or group of gaping wayfarers for miles, keeping always a little in advance and scrutinising each individual with a rigorous eye. Here and there a laughing-jackass gave forth its mocking laugh, as if to scoff, and ridicule each new trespasser to its territory. Now and then the gentler, sweetly simple strains of smaller birds were heard. Those who say this country is lacking in songbirds can never have wandered in its more secluded woodlands. True, we have no songbirds whose sustained and elaborate harmonies rival those of Europe’s most boasted melodists, but we have many whose simpler strains delight the ear and touch the heart of those who would but listen. They who are accustomed to the remote bush will be aware that several of our meek little vocalists continue their summer song far into the night if the moon be shining, or if intervening vapour does not tarnish the brightness of the stars.” Photo: J. Gramp. Kookaburra 8. Reading 3 Adelaide in 1839 from the South Australian Register 15 January 1878 (reproduced with the kind permission of The Wakefield Press). “But my present theme is Adelaide, the future city. The condition of the settlement had not much varied when I arrived, in the early part of the year 1839, to that described by Mr Horton Jones in his written account of it as beheld by him in 1838. The first sign of civilisation to be seen was a number of rudimentary huts along the town’s northern boundary. They were made of reeds from the nearby Torrens River and as I later discovered were collectively referred to as Buffalo Row, after the vessel in which their first residents arrived. Image: Wiki Commons. Adelaide, North Terrace 1839, looking south-east. Soon after passing these huts more buildings came into view, firstly small huts and cottages, then sprinkled here and there a few more substantial buildings. One quite enormous structure belonging to the South Australian Company, another good brick house to Mr Hack, another to the enterprising Mr Gilles, one to Mr Thomas, and a couple of new taverns. But in the main the rest of the dwellings were small and made of very light materials; and the number of canvas tents and marquees gave some parts of the settlement the appearance of a camp. Most of the newcomers settle down on what is called the Park Lands, where they are handy to the rivulet, and they construct a Robinson Crusoe sort of hut with twigs and branches from the adjoining forest. In this fine and dry climate these huts answer well enough as temporary residences. The principal streets have been laid out in the survey of the town and are 132 feet wide, which is nearly twice as wide as Portland-place, and the squares are all so large, that if there were any inhabitants in them a cab would almost be required to get across them. Some critics of the Surveyor’s design for the town, especially in regard to the enormously wide streets, the expansive squares and the surrounding belt of parklands, openly complained of wasted space. ‘And how will the case stand 50 years hence,’ they asked, ‘ seeing that by Act of Parliament the limit of the city can never be extended?’ Certainly at the outset the large extent of bush-like township often occasioned much individual inconvenience. People began to build in all parts of it and very small villages and solitary houses were scattered here and there. I remember during the first conversation with Captain Sturt, offering a suggestion that strict regulations should be reinforced to ensure that the town should progress in a more orderly fashion extending gradually from the centre to the four terraces. Captain Sturt concurred with this suggestion, as he did with another that I made in due course. My idea was that if the city had been placed wholly on the north side of the river on a portion of the raised tableland which extends from Montefiore Hill to Dry Creek, the plain on which South Adelaide stands would have been a more suitable suburb for dairy farms and the production of fruit, flowers and culinary vegetables. However, when told of this among complaints from a variety of sources, Colonel Light was adamant that his original plan was to be adhered to in every respect. Time alone will determine the wisdom or otherwise of his unflinching determination.” 9. Reading 4 Extract from the foreword of Pre-European Vegetation of Adelaide: a Survey from the Gawler River to Hallett Cove, by Darrell N. Kraehenbuehl, 1996 (reproduced with the kind permission of The Nature Conservation Society of South Australia Inc., Adelaide. More information and resources can be found at http://www.ncssa.asn.au/). Foreword “Less than five per cent (of the original vegetation) has been left relatively untouched, and even less reserved for the future. … But this is no backward-looking lament. Rather it is a call to action – a call to salvage the remaining pieces, to restore them so once again a sense of their former glory can be glimpsed and this time appreciated and kept intact for future generations. It is not enough just to save the plants in their unique assemblages. Gone with even less trace are the myriad of birds, reptiles, frogs, and freshwater organisms as well as the mammals that once called this part of Australia home. Photo: J. Gramp. Echidna While there is reference to the million or so birds in the reed beds of the past, little remains to tell of the passing of the wombats, echidnas, barred bandicoots, pygmy-possums, numbats, bilbies, quolls, bettongs, wallabies, hopping mice, dingoes and numerous other forms. Were there a quarter of a mission of each of these species once living in the ‘vicinity of Adelaide’ but now wiped off into oblivion? Will we ever know? Maybe not. … The colonial period and the early twentieth century Many people have the erroneous belief that Europeans were the sole cause for the impoverishment of the native flora. While this is substantially true, some of the cause may be attributed to the pre-European inhabitants, the Australian Aborigines. Their burning practices across the plains and in the adjacent Mount Lofty Ranges over many centuries would inevitably have had an impact upon the ground-storey plant species, even perhaps converting some woodland areas and forest to tall shrubland and grassland. … Some of the first European settlers, camped around lagoons at Holdfast Bay, were careless with fires which, on a number of occasions, threatened their tents and property. … Other fires are said to have destroyed large areas of kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra) and set alight rushes and reeds that grew around the edge of the lagoons.” 10. Attachment two: Assessing biodiversity group worksheets Assessing biodiversity - Group 1, task 1 (copy trees and canopy back-to-back). Investigating trees - This activity enables you to identify the habitat value of trees within the study area. Background notes Trees (including those that are dead) are an important component of an ecosystem as they provide habitat (food, shelter, nesting space, protection from predators) for many animals, as well as canopy cover for many interdependent smaller plants (shrubs, grasses, ground covers, climbers, moss, lichen). In addition, their fallen leaves (leaf litter) and branches contribute to soil moisture, and soil health, by putting organic matter back into the soil naturally, and providing habitat for helpful micro-organisms which thrive there. Large trees often provide better habitat as they contain more hollows than small trees, however these hollows can take up to 120 years to form! Because they are old, large trees are difficult to replace. Nesting boxes provide suitable alternative nesting spaces for birds and other animals if there are no large trees with hollows in your study area. Large trees are nature’s skyscrapers and are important as they provide food and shelter for many different types of animals. Birds such as Rainbow Lorikeets need hollows for survival Photo J. Tyndall Materials This worksheet, map of selected area, pencil, calculator and tape measure. What to do Step 1: Walk around the selected area and record on your map each tree that you find (dead trees may also be included). Step 2: Identify whether most of the trees are native to Australia (i.e. gum trees) or exotic (introduced from another country) and record your answer. Step 3: Record the circumference of each tree. Step 4: Record if the tree is a large tree (i.e. has a circumference of more than two metres measured 1 metre from the ground). Step 5: How many large trees are found in the study area? Step 6: How many large, native trees are found in the study area? Total number of trees = As a group discuss potential actions that your school can undertake to protect and improve the number of large, native trees in the study area. 11. Assessing Biodiversity - Group 1, task 2 Investigating canopy cover - This activity enables students to measure the quality of the tree canopy cover within a defined area. Background notes The canopy layer in a forest refers to the highest level of growth (i.e. the branches and leaves in the crown of trees). The canopy layer of an ecosystem is important as it provides habitat and protection from predators for birds and small mammals such as possums. It also provides an organic layer of leaf litter for the forest floor which is broken down into important soil nutrients by microorganisms and helps to retain soil moisture. Canopy cover describes the proportion of the ground that is shaded when the sun is directly overhead and is a measure of the condition of the trees. If a tree is stressed or sick it will have a lower than average canopy cover. Materials This worksheet, digital camera (optional) and pencil. This is approximately 60-70% canopy cover The activity Photo J. Tyndall Estimate the % canopy cover for your area of study. REMEMBER: you should factor-in the areas covered by trees and the areas between trees. Enter your estimate of canopy cover. Illustration of canopy cover Reproduced with kind permission of the Nature Conservation Society of SA As a group discuss potential actions that your school can do to improve canopy cover in your school grounds. 12. Assessing Biodiversity - Group 2 Investigating understorey - This activity enables students to identify the habitat value of understorey within the study area. Background notes Vegetation can be classified into 3 separate layers: overstorey (plants greater than 5m tall); understorey (plants between 5m – 0.5m); and the herb layer (non-woody plants less than 0.5m in height). The greatest richness of plant species at a site will almost always be found in the understorey and herb layer level of an ecosystem. These plants are important because they provide a food source, shelter and create suitable conditions for larger plants to grow in (e.g. shelter, shade and maintenance of soil moisture and nutrients). Unfortunately, these layers (especially the herb layer) are often the most easily impacted upon by disturbance and are the hardest to re-establish. Materials Understorey, such as native paper daisies are important This worksheet and a pen. Photo J. Tyndall The activity Estimate the percentage cover of understorey in the study area and record it. Also record the types of vegetation present in the study area. As a class discuss potential actions that your school can do to protect and improve understorey in your study area. What to do Step 1: Walk around the study area and estimate the percentage cover of native understorey vegetation. Step 2: Tick below the numbers and types of vegetation you find in the study area: Types Numbers Name (if known) Tree > 5m Shrub (1-5m) Small shrub < 1m Large herb > 0.5m Small herb < 0.5m Fern Moss/lichen Scrambler/climber Tall grass (or grass like) > 1m Small grass (or grass like) < 0.5m Other As a group discuss potential actions that your school can undertake to improve the understorey in your school grounds. 13. Assessing biodiversity - Group 3, Task 1 (copy organic litter and logs and rocks back-to-back). Investigating organic litter - This activity enables you to understand the habitat value of organic litter within the study area. Background notes Organic litter is defined as materials that are no longer attached to a plant and have fallen to the ground. This includes things such as fallen leaves, twigs, tanbark, mulch and small branches less than 30cm circumference. Organic litter is important because it provides habitat and a food source for many creatures such as insects, spiders and small reptiles. It also breaks down to provide soil nutrients, influences the soil microclimate (i.e. the temperature, moisture level, structure and composition) and influences which plants can grow. Materials - This worksheet and a pen. Organic litter provides habitat and a food source The activity Photo C. Hall Walk around the study site and estimate the percentage cover of organic litter found in the study area and record it. As a class discuss potential actions that your school can do to increase the organic litter in your study area. Organic litter includes things such as fallen leaves, twigs, tanbark, mulch and small branches less than 30cm in circumference. What to do: Step 1: Estimate the percentage of the study area covered by organic litter. Percentage of organic litter coverage = Step 2: Does the quality of the organic litter vary across the site? Yes / No. How? As a group discuss potential actions that your school can undertake to improve the amount of organic litter in the school grounds. 14. Assessing biodiversity - Group 3, Task 2 Investigating logs and rocks - This activity enables you to discover the importance of logs and rocks as habitat within the study area. Background notes Logs whether small, large or rotting provide perfect shelter and nesting places for a range of different animals including echidnas, reptiles, spiders and insects. Logs also provide a food source for insect-eating birds that forage around fallen logs and are an important habitat for frogs as they retain moisture. Unfortunately, people often remove fallen logs from their property or from bush for firewood – reducing the amount of habitat available for these species. Rocks also provide shelter for animals. Materials This worksheet, pen, tape measure. The activity Logs provide shelter and nesting places Photo C. Hall Step 1: Walk around the study area and record on the worksheet the number of logs and rocks present and measure the area of ground they cover. Logs include stumps, fallen trees or branches that have a circumference of at least 30cm (approximately the size of an adult’s ankle) or a diameter of at least 10cm. Disturb the logs as little as possible and be wary of spiders and snakes. Step 2: Add up all the measured areas of ground covered with logs or rocks and enter the result. Total area covered by rocks and logs = As a group discuss potential actions that your school can do to increase the number of logs and rocks in your study area. 15. Assessing biodiversity - Group 4 Investigating weediness. This activity enables you to identify environmental weeds in the study area. Background notes Weeds are plants that grow in an area where they are not wanted. They are usually exotic species (however can also include native Australian species) and can compete with and limit the growth of indigenous plants. Weeds impact on native insects, birds and animals as they reduce the food source that indigenous plants provide. Weeds also impact on agriculture and the economy, threatening the sustainability of natural ecosystems and agricultural production. Environmental weeds are plants that threaten natural ecosystems. They can invade native areas and out-compete the plants, resulting in a reduction of plant diversity and loss of habitat for native animals. Weeds can be carried into an area by wind, water, people, animals, vehicles, machinery or they can escape from gardens. It is important to appropriately dispose of weeds - dumping of garden waste in the bush is also a way in which weeds spread. Materials This worksheet, weed identification books or a small, recognisable selection from a list of environmental weeds found in your local area, pen. The activity Using the weed identification books/lists identify the 5-10 most common environmental weeds to look for in the study area. Provide photos of weeds to look for. Your local council may have publications to assist with identifying weed species in your local area, or you could use this webbased tool by clicking here. Step 1: Walk around the study area and search for environmental weeds. Step 2: List the different types of environmental weeds that you find in the table below. Step 3: Estimate the percentage cover of weed species found in the study area. Environmental weed species Common name Scientific name (if known) % of coverage As a group discuss potential actions that your school can do to reduce the number and impact of environmental weeds in your study area. This resource was developed by a teacher with the support of the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board through its NRM Education program. Your local NRM Education Officer provides support for sustainability initiatives at your school. These include learning more about sustainability, environmental auditing, and developing biodiversity, nature-play or food gardens. Click here to view our website. Please note: due to current updating of our website some of these links may not work at the time you are trialling them. We apologise for any inconvenience and will ensure the links are working once the units are reviewed and uploaded to the new site.