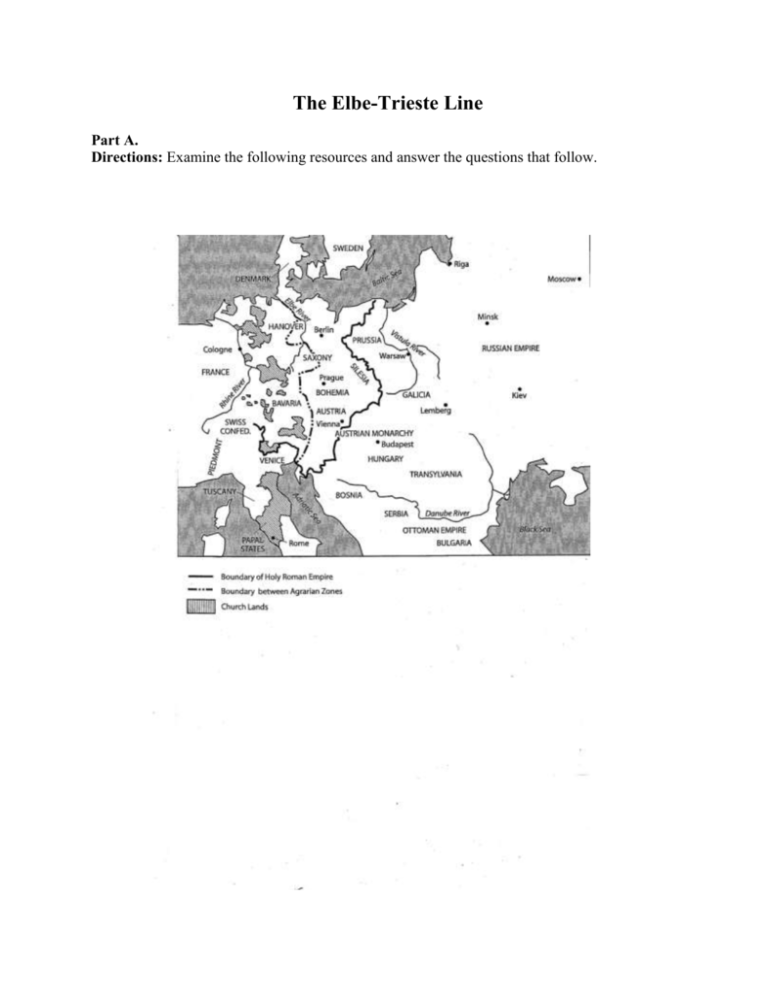

The Elbe-Trieste Line

advertisement

The Elbe-Trieste Line Part A. Directions: Examine the following resources and answer the questions that follow. The Agricultural Revolution in England Many landowners, seeking to increase their money incomes, began experimenting with improved methods of cultivation and stock raising. They made more use of fertilizers (mainly animal manure); they introduced new implements (such as the drill seeder and horse-hoe); they brought in new crops, such as turnips, and a more scientific system of crop rotation; they attempted to breed larger sheep and fatter cattle. An improving landlord, to introduce such changes successfully, needed full control over his land. He saw a mere barrier to progress in the old village system of open fields, common lands, and semicollective methods of cultivation. Improvement also required an investment of capital, which was impossible so long as the soil was tilled by numerous poor and custom-bound small farmers. The old common rights of the villagers were part of the common law. Only an act of Parliament could modify or extinguish them. It was the great landowners who controlled Parliament, which therefore passed hundreds of "enclosure acts," authorizing the enclosure, by fences, walls, or hedges, of the old common lands and unfenced open fields. Land thus came under a strict regime of private ownership and individual management. At the same time small owners sold out or were excluded in various ways, the more easily since the larger owners had so much local authority as justices of the peace. Ownership of land in England, more than anywhere else in central or western Europe, became concentrated in the hands of a relatively small class of wealthy landlords, who let it out in large blocks to a relatively small class of substantial farmers.1 A French Peasant's Attitude toward the Old Regime I am miserable because they take too much from me. They take too much from me because they do not take enough from the privileged classes. Not only do the privileged classes make me pay in their stead, but they also levy upon me their ecclesiastical and feudal dues. When, from an income of a hundred francs, I have given fifty-three francs and more to the tax collector, I still have to give fourteen to my seignior and fourteen more for my tithe and out of the eighteen or nineteen francs I have left, I have yet to satisfy the excise-officer and the salt-tax-farmer. Poor wretch that I am, alone I pay two governments – the one, obsolete, local, which today is remote, useless, inconvenient, humiliating, and makes itself felt only through its constraints, its injustices, its taxes; the other, new, centralized, ubiquitous, which alone takes charge of every service, has enormous needs and pounces upon my weak shoulders with all its great weight. 2 1 R. R. Palmer et al., A History of the Modem World, 9th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), 429-30. Hippolyte Taine, Ancien Regime, quoted in The Era of the French Revolution, Louis R. Gottschalk (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1929), 39. 2 Russian Aristocrats and Serfs The Russian peasants lived isolated in their villages; the nineteenth-century Russian revolutionary Alexander Herzen described them as "that magnum ignotum, that people – muted, poor, semi-barbarous – which concealed itself in its villages, behind the snow, behind bad roads, only appearing in the streets of Saint Petersburg like a foreign outcast, with its persecuted beard and prohibited dress – tolerated only through contempt." And those peasant villages were far distant from twentieth-century daydreams about rural communities; they were small, squalid collections of mud huts within whose dank precincts the families from elders to children gathered in concentric rings of precedence around the lifegiving stove. Here the laws on beards and clothes penetrated only vaguely and here the foreign fashions of Petersburg were seen only during the summer visits of the serving gentry; the peasants themselves wore their homespun blouses, shaggy sheepskin jackets, and baggy trousers, and wrapped their feet in cloth for the cruel winters or shuffled in bark sandals. Here came no news of distant Amsterdam or London, no plays fresh from the Paris stage; here rather the small church staffed by its priests no richer and no more educated than the peasants themselves served their souls and their bodies through their short and narrow lives; existence revolved around three recurring rituals of birth, marriage, and death. . . . The peasant's attitude toward his government was doubly disturbed. On the one hand, the government was the agency which ordered his conscription; no peasant parting for twenty-five years of service in the army could reasonably expect to see his family again. He was forced to fight in distant climes for advantages quite unclear to him and for a Tsar who seemed more a foreigner than an all-protecting father. If the peasant escaped the annual harvesting of troops, he might just as easily find himself ordered to the distant Don or to Ingria on some labor project. And if he were a state peasant who escaped either conscription, perhaps he might be honored by a trip to the Urals for "temporary" work in the mines and forges, or find his village purchased by some strange industry. If by some incredible stroke of fortune he survived all these attentions, he could be certain that the burden of taxes would grow incessantly and that the new poll tax would ignore his privileges and customary distinctions and lump him and all his cohorts across the land into one desperate serfdom.3 3 L. Jay Oliva, Russia in the Era of Peter the Great (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1969). 109-10. Cartoon A A Russian landowner in Oriental garb addresses his serf. Cartoon B A French peasant, depicted as one of the barnyard animals, addresses a French noble. Cartoon C An English yeoman, driven off the land by an enclosure act, is ignored by a wealthy landowner. 1. After World War II, what line in modern Europe appeared to resemble closely the ElbeTrieste line? 2. What characteristic appears to be the major distinction between the two agrarian zones in 18th century Europe? 3. In which country does the position of the peasant appear to have been the least humane? 4. Which of these three states in the eastern agrarian zone – Prussia, Hungary, or Russia – was the least "Western" in character? 5. In which state was the peasant the most estranged from the ruling class? 6. In which country was the economic security of the agrarian workers the most unstable? 7. Which group of peasants suffered from an agricultural revolution during the 18th century? 8. Which state appears to have employed a process of double taxation? 9. In which state does it appear that an industrial labor pool was being made available? 10. How would you account for the numerous peasant rebellions in Russia when peasant disturbances in England and France were minimal during most of the 18th century? 11. Today, how far to the east has the traditional division between the two worlds shifted? How do you account for the change? 12. What conclusions can you draw regarding the significance of the Elbe-Trieste line in modern European History?