End-of-Life Care for Older People

advertisement

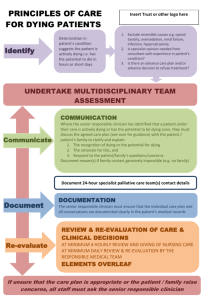

End-of-Life Care for Older People in Acute and Residential Care Settings Eamon O’Shea Introduction 1. This short paper deals with end-of-life care for older people in Ireland. About 29,000 people die in Ireland each year, the majority of whom are older people. Nearly three quarters of people die outside their own home, while more than two fifths die in acute hospitals. The focus of my presentation is on end-of-life care for all types of illnesses and conditions in acute and residential care settings because this is where the majority of older people die in Ireland. 2. End-of-life care is broader in scope than palliative care and allows a longer lead time to death. It takes into account the potential uncertainty surrounding dying and death, including the possibility that some people follow complex and non-linear pathways to death. End-oflife care is intimately bound-up with quality of life issues for older people living in acute and long-stay care settings. Loss and decline are common and recurring features of life in longstay care settings, from admission, through on-going care, to death. The challenge for the future will be to find an equilibrium between the care of the living and the dying in acute and long-stay care settings. What is needed is an integrated care structure for end-of-life care that embraces living and dying as part of the normal care structures and processes in all care settings. 1 Ethical Issues 3. The key challenge in enhancing quality of life for older people at end-of-life is the preservation of the person’s surviving autonomy and dignity balanced against inevitable paternalism. Respect for the person’s dignity and autonomy are at the core of their human rights and the law on consent upholds these rights. The current law on decision-making at the end-of-life is based on the principles of autonomy and self-determination. However, if these principles do not hold during all of their time in care, beginning at admission, it is difficult to give them meaning at the end stage of dying and death. The first challenge therefore is to involve older people directly in all matters related to their care. This means more information and enhanced communication between providers of care, families and patients. In Ireland, there is also a need for continuing reform in relation to vulnerable older people and the issue of capacity. Beginning with the transition from home, and having regard to the least restrictive alternative, the person’s wishes should be considered at all stages of the care process. In this regard, knowledge of the patient’s wishes or any advance directive made prior to the onset of incapacity should be central to decision-making, for example in relation to people with dementia. While there is currently no legislation at present to underpin advance directives, they are a means of ensuring wishes are respected following the onset of incapacity and not just at the end-of-life. Facilities, Services and Procedures 4. While the majority of older people in Ireland die in acute and long-stay settings, the number of designated palliative care beds in both of these systems remains extremely low. The availability of single rooms at time of death is also a problem, particularly in public residential care and some acute hospitals. Neither do staff in these settings tend to have formal qualifications in palliative care, with less than one third of all facilities reporting that 2 their qualified nurses hold a post-registration qualification in palliative care; the corresponding figure for doctors/consultants is just 12 per cent. These figures suggest a significant education and training gap in relation to palliative care provision. 5. In addition, there is low provision of formal bereavement support structures available before and after death within acute and long-stay settings in Ireland. Similarly, the availability of private space for engaging in confidential consultations with relatives and friends is scarce in all settings. Moreover, there is very little internal accommodation available for family and friends wishing to stay overnight with their loved-ones when death is imminent. 6. Written guidelines for end-of-life care are generally more available in the private long-stay sector than in the public or voluntary long-stay sector. Care in the last hours of life, last offices and contacting a patient’s priest/minister/spiritual advisor are well covered in written guidelines, achieving 80 per cent coverage or above in public, private and voluntary facilities. Symptom control and informing other patients of the deaths of relatives are less well covered. The existence of written policies on advance directives is low overall, particularly in public long-stay facilities. Similarly, coverage in relation to written policies/guidelines on the needs of residents from ethnic minority groups is low across all sectors. Living and Dying Experiences 7. Our research on death and dying, which is now five years old, showed that older people were capable of conceptualising end-of-life issues, but were less willing to talk about their own position on the end-of-life continuum. There was recognition of loss and transition upon admission to long-stay care, but no overt willingness to engage in discussion about the 3 possibility of their own death. It is impossible to know if this kind of response was selfdeception or self-protection, or some combination, on the part of patients. 8. Information and openness around dying and death are contentious issues. In our research, only a small number of long-stay care staff regarded it as part of the patient’s rights to be informed of their prognosis, in keeping with the general belief that discussion of death was unsettling for residents and therefore not to be encouraged. The majority of staff only discussed death and dying if the resident brought up the topic first and acknowledged that they were dying. Inhibitory factors against open communication included a perceived lack of knowledge and skills among staff and finding the right time and place to raise the subject with them. Strategies such as keeping cheerful, reassuring the resident that they would be fine and distraction were used to steer staff-patient discussions away from death. 9. When death was explicitly acknowledged by patients, being able to achieve a sense of closure over their life was important. Patients often rationalised their deaths either through a belief in God as an external influence on the time and manner of death, or as a normal and inevitable pattern of the life-cycle. Some patients reported that they not only accepted but actually looked forward to death as a way of meeting again with family members who had pre-deceased them. A ‘good’ death, when articulated, was described generally as one which was neither protracted nor painful, but allowed for reconciliation with family and friends. Most people were aware of the need to balance physical care with the spiritual dimension of life closure. 10. Staff shortages and turnover, allied to the absence of specialised care, can often undermine the realisation of a person-centred model towards the end of life. Very often, staff 4 do not have the time to give dedicated personal care to patients who are dying. There is also significant emotional labour involved in caring for people at end-of-life, making it difficult for staff to move seamlessly between care of the dying and care of the living. The availability of education and training in end-of-life care is a necessary counterbalance to the physical and emotional needs of the job. Dementia 11. There is evidence that people with dementia, with or without a co-morbidity, do not always have access to adequate end-of-life care when death is imminent. Internationally, studies have shown that patients with dementia are often subject to unnecessary investigations during the terminal phase of their illness, that cognitively impaired patients are prescribed less analgesia in the last six months of life compared with cognitively intact people and that there is a high prevalence of antimicrobial treatment of suspected pneumonia episodes in nursing home residents with advanced dementia, which is associated with prolonged survival but not necessarily with improved patient comfort. 12. In considering end-of-life care, there are important differences between dementia and other terminal diseases: in dementia, prognosis is less predictable and the diagnosis and evaluation of pain is often more difficult due to challenges communicating with the person with dementia. Globally, there are few palliative care facilities that accept people with dementia. In Ireland, people with dementia tend to die in residential care, or at home, without palliative interventions. Little is known about palliative care for people presenting with advanced chronic illness and dementia: in these patients, it is often the co-morbidity, rather than dementia, that guides the approach to care in terms of structure, process and practice. 13. Palliative care has focused traditionally on care for cancer patients in the terminal phase of their illness. There is growing evidence internationally of a desire to extend palliative care 5 services to include all people in need of specialist care when terminally ill, including those with chronic diseases such as dementia. A report on palliative care in Belgium acknowledges that people with dementia have specific needs that are frequently overlooked in discussions on palliative care. A recent study from the UK aiming to identify the key end-of-life issues for people with dementia concluded that transition to good quality end-of-life care continues to be the exception rather than the rule for people with dementia. The authors recommend improved collaboration between different health care sectors and increased training in dementia for professionals in the palliative care sector. The European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) has drafted a white paper on optimal palliative care for people with dementia, which was published earlier this year. Conceptualising New Approaches to Care 14. There are many barriers to the development of new conceptual approaches that seek holistic, person-centred solutions to end of life care for older people in Ireland. There are resource constraints, capacity problems, infrastructural weaknesses, education deficiencies, and poor attitudes and expectations in relation to quality of life for older people at end-of-life. Ageism within society generally and within the health and social care system in particular makes it sometimes difficult to sanction investment in end-of-life care for older people. 15. End-of-life care must be flexible, contemplative and responsive to need in order to capture the uncertainty associated with dying and death. Trajectories of dying are not always linear, as older people move in and out of the zone of ‘living and dying’. Neither are losses within long-stay facilities in particular confined to individual dying and death; older people have to come to terms with many ‘absences’ within long-stay care and bereavement is a constant feature of life in such settings. Therefore, the neat separation of end-of-life into a 6 defined period when palliative care services can be mobilised and administered is not always possible or desirable. The need for end-of-life care can arise far away from actual death, depending on the physical, mental and emotional state of patients and their families. Conclusions 16. Four key conclusions arise from this summary paper. The first is for greater consultation with older people in order to establish expressed needs and preferences with respect to endof-life care, if necessary through greater use of advance directives. The second is for an improvement in the physical environment where people die, particularly with respect to the availability of single rooms and bereavement services and facilities for families and friends. The third is for greater awareness and understanding of dying and death, developed mainly through enhanced education and training for staff in all care settings. This is necessary to deal with basic issues like pain and symptom management, the management of psychological symptoms, personhood, and, increasingly, cultural differences between staff and patients. The fourth is for policy reform to ensure that end-of-life care and bereavement are recognised as important public health issues, separate to palliative care but inclusive of many of its key elements. This would help to promote a continuum of care, incorporating fundamental, enhanced, advanced and complex interventions, designed to respond to the multi-faceted needs of people at end of life, particularly those with dementia. 7