Routines as Patterns of Behavior

advertisement

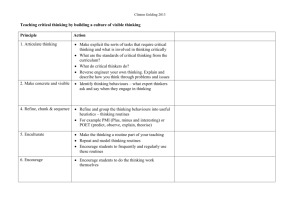

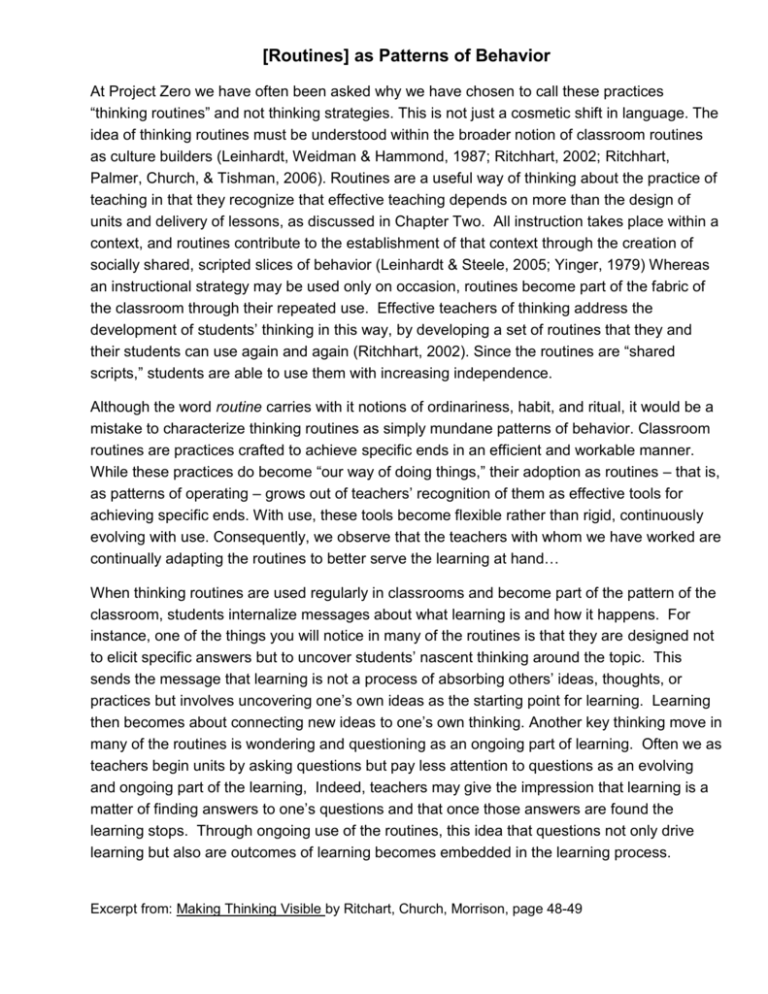

[Routines] as Patterns of Behavior At Project Zero we have often been asked why we have chosen to call these practices “thinking routines” and not thinking strategies. This is not just a cosmetic shift in language. The idea of thinking routines must be understood within the broader notion of classroom routines as culture builders (Leinhardt, Weidman & Hammond, 1987; Ritchhart, 2002; Ritchhart, Palmer, Church, & Tishman, 2006). Routines are a useful way of thinking about the practice of teaching in that they recognize that effective teaching depends on more than the design of units and delivery of lessons, as discussed in Chapter Two. All instruction takes place within a context, and routines contribute to the establishment of that context through the creation of socially shared, scripted slices of behavior (Leinhardt & Steele, 2005; Yinger, 1979) Whereas an instructional strategy may be used only on occasion, routines become part of the fabric of the classroom through their repeated use. Effective teachers of thinking address the development of students’ thinking in this way, by developing a set of routines that they and their students can use again and again (Ritchhart, 2002). Since the routines are “shared scripts,” students are able to use them with increasing independence. Although the word routine carries with it notions of ordinariness, habit, and ritual, it would be a mistake to characterize thinking routines as simply mundane patterns of behavior. Classroom routines are practices crafted to achieve specific ends in an efficient and workable manner. While these practices do become “our way of doing things,” their adoption as routines – that is, as patterns of operating – grows out of teachers’ recognition of them as effective tools for achieving specific ends. With use, these tools become flexible rather than rigid, continuously evolving with use. Consequently, we observe that the teachers with whom we have worked are continually adapting the routines to better serve the learning at hand… When thinking routines are used regularly in classrooms and become part of the pattern of the classroom, students internalize messages about what learning is and how it happens. For instance, one of the things you will notice in many of the routines is that they are designed not to elicit specific answers but to uncover students’ nascent thinking around the topic. This sends the message that learning is not a process of absorbing others’ ideas, thoughts, or practices but involves uncovering one’s own ideas as the starting point for learning. Learning then becomes about connecting new ideas to one’s own thinking. Another key thinking move in many of the routines is wondering and questioning as an ongoing part of learning. Often we as teachers begin units by asking questions but pay less attention to questions as an evolving and ongoing part of the learning, Indeed, teachers may give the impression that learning is a matter of finding answers to one’s questions and that once those answers are found the learning stops. Through ongoing use of the routines, this idea that questions not only drive learning but also are outcomes of learning becomes embedded in the learning process. Excerpt from: Making Thinking Visible by Ritchart, Church, Morrison, page 48-49