“Power of Beauty”: Promoting Gender Stereotypes in Inter

advertisement

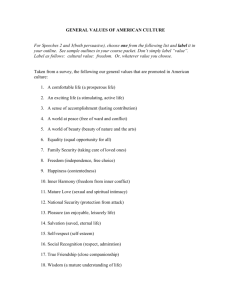

Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) The “Power of Beauty”: Promoting Gender Stereotypes in Inter-War Greece Dr Maria Kyriakidou, Associate Professor, American College of Thessaloniki Abstract During the 1920s new concepts on the body’s malleability and its ability for improvements appeared. Western societies placed emphasis on youth and beauty encouraging the belief that the latter was a matter of health. Of course, these new proclamations were gender and class specific, as women were judged by their looks more than men and upper class women were more prone to the quest for the standard aesthetic ideal than their working class counterparts. It is only very recently that research in this field has been undertaken in an international context since feminist literature introduced the historical analysis of personal appearance, physical well-being and cultural definitions of a healthy and agreeable, gendered body. This paper thoroughly examines an inter-war etiquette book entitled ‘Counsel on female beauty’. Through the content analysis of the text, one can clearly see the creation of cultural stereotypes about feminine beauty, the promotion of an a-historical view of women’s pre-occupation with beautification and of a universal, essentialist femininity. It is also apparent that women’s occupation with beauty, when linked to health and suggested by medical doctors, was not seen as frivolous and vain but as the designated attitude for every woman. Keywords: Inter-war Greece, Beauty, Prescriptive Literature, Gender Stereotypes, Body Image Introduction This paper undertakes a content analysis of a primary source (a counsel book that belongs to the genre of ‘prescriptive literature’), which addressed matters of women’s beautification in the specific historical context of interwar Greece. It is widely accepted that this historical period in Greece initiated a stage of rapid change, reforms, social modernisation and rationalisation and brought about changes that involved gender roles and identities (Veremis, 1989, pg. 15-25, Mavrogordatos, 1988, pg. 9-19). In western thought, the process of modernization can be understood as the transition from ‘simple’, homogenous societies to ‘complex’, highly differentiated ones, which were associated with socio-economic change Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) (industrialisation, capitalism and urbanization) as well as with rationalization and intellectual progress, in short, with the Enlightenment philosophy. Modernization brought about the ascendance of the nuclear family, a process which involved gender, both in its biological and in its social sense; as women were thought to be confined inside the older, private boundaries as products of nature and not of society (Marshall, 1994, pg. 6-15, 148). Most theories of modernity referred to the distinction between the public and the private sphere, a classic leit-motif of international works on women’s sphere, especially in the inter-war period. The distinction between the private and the public realm was used to identify male and female roles and to shape gender identities by acting powerfully in various political contexts, both in everyday behaviours and in formal political spheres (Radcliffe, 1993, pg. 197-218). The public/private dualism was founded upon the sexual dimorphism, which was equally applied to the public world and the private realm. The dominant patriarchal society perceived the two spheres in opposition to each other and women were in general limited to the private one (Jelin, 1990, pg. 184-93). An early twentieth century ‘ideal body of femininity’ was culturally constructed (Comiskey, 2004, pg. 31) as an outcome of modernization. The question regarding the degree to which ‘beauty matters’ constituted the subject matter of philosophical interest in aesthetics, ethics and cultural criticism. In the contemporary western socio-cultural context, a new approach to the philosophical theorizing of beauty places questions of gender at the forefront of assessment of our daily experience (Brand, 1999, pg. 1). At the same time, the issue of beauty is clearly a challenge for feminist theory. The vast majority of feminist studies from the nineteenth century onwards view current practices of feminine beautification as an oppressive element of a patriarchal society, while only a few among the most recent analyses discuss the potential evolutionary, and even empowering, aspects of embellishment (Singh and Singh, 2011). New voices in feminist theory discuss the ‘possibility of a feminine aesthetic’ under certain conditions and the variation of gendered perspectives on beauty (e.g. see Brand and Devereaux, 2003, pg. ix; Goodman, Morris and Sutherland, 2008). It is evident that the process of beautification took, and still takes, up a great deal of time in many women’s lives and it is seen as the source of both anxiety and pleasure for women. That gave feminists the opportunity to challenge past views in the light of its connection to embodiment, aesthetic creativity and the development of a distinct female subjectivity. It has been equally argued that feminine beautification can be seen as a pleasure if only perceived and constituted as freely chosen, that means free from the so Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) called ‘male gaze’, which truly permeates major aspects of women’s lives (Cahill, 2003, pg. 42-4) and was the dominant influence in the context of the inter-war female experience. Cross-culturally and in different historical contexts, female bodies are always subject to ‘what becomes a powerful enactment of the ‘male gaze’. This gaze is internalized [by women] and reinforces female objectification… [Thus,] social constructions of women’s bodies become accepted norms’ (Younger 2003, pg. 47). The ‘Counsel of Female Beauty’ : Key Themes The emerging norms discussed above were spread throughout Europe and reached Greece through the mediation of western-educated physicians and doctors. One of the products of such mediation is the book under study in this paper. The ‘Counsel of Female Beauty’ was written by Mr. Renos, an author ‘educated in Europe and the United States’ with the co-operation of a physician, Dr. Roussakis, and was published in Athens in 1928. The emphasis on the author’s studies in the western world and the co-authoring of the book by a medical doctor are employed as a guarantee for the ostensibly modernized and highly scientific content of their book. The authors of the book already at the very beginning of their work assume that the ideal standard of female beauty projected here and the authority they claim on such matters are inextricably linked to the ‘male gaze’: ‘Women are judged by their looks more often than men and they are strictly judged… In this light, women should be able to stand inspection by every familiar or unfamiliar observing eye’ (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 5). Even though the beauty guide is described by the authors as a book that is ‘indispensable to every lady and in short to every family’, a glance at its contents suggests that it is addressed primarily and, almost exclusively, to women of the upper middle bourgeois class, an emerging class in inter-war Greece. Furs, as well as imported and expensive embroideries and laces, are viewed as inseparable elements of female attire (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 187-8) and the ingredients of the beauty poultices prescribed are rare and costly; thus, impossible to be bought by working class women. Such a finding is well in line with results from analogous studies on contemporary Western Europe where it is also noted that most prescriptive literature authors spoke directly and primarily to bourgeois women (Hanna, 2003, pg. 331). Nevertheless, the authors make an effort to overcome historical and class-related differences of a woman’s desire to appear beautiful. Female coquetry is presented as a universal, a-historical value with a biological basis, as well as a need felt by all women, irrespective of their social background. It is quoted that ‘if one day God could fulfill one and sole desire of every human being, women, irrespective of their intellect, social status or age would definitely ask God for beauty’ (Renos and Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Roussakis, 1928, pg. 3). To support their claim that this urge is ‘natural to women’ the authors refer to archaeological findings suggesting that even in the very early societies women made use of different beauty care aids (ibid, pg. 8-9). The authors’ historical retrospection includes a reference to an ancient Greek ideal of beauty, which was actually defined as ‘the harmonious build of the body and the face’. Specific biological terms and precise numerical measures are used to define the perfect proportions of the female face and body (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 6). The belief that coquetry is ‘so natural to womankind that none should place negative judgments on women who practice it’ is presented as an innovative viewpoint brought about by novel achievements of science. This supposedly eternal truth is promoted as ‘justifiable’ and ‘natural’, explained by biological as well as by social reasons. The view that women compete with each other in the field of beauty is a recurring theme in the counsel book: ‘a woman should struggle to preserve her image in an impeccable condition since her rivals are always eager to take her place’ (ibid, pg. 11). So it was claimed that ‘beauty is the only way women could gain anything in our society in which… none ever denied the irresistible power of beauty… If the woman carefully safeguards her beauty many are ready to serve her and everyone will satisfy her wills’ (ibid, pg. 3-4, 11, my emphasis). The same belief was not alien to contemporary Western Europe. Various sources on the same subject in inter-war French society, for instance, noted that ‘being considered attractive was necessary for social advancement and in certain jobs in the public eye’ (Comiskey, 2004, pg. 37-8). The body had to conform to accepted social norms and the need to appear attractive was claimed to be ‘born from the needs of modern life’ (ibid, pg. 43). The urge for beautification did not anymore involve a handful of uncommon cases of eccentric women, but it became a necessity associated with the social pressure to be attractive. In addition to the rise in social status, beauty would improve the marital prospects of women and in general they could be more successful in life, both at the family level and in the public domain. On the other side of the Atlantic, USA moralists objectified women by claiming that ‘women were first and foremost, bodies to be assessed on the basis of visual appeal’. To this it was added that ‘beauty itself is an essential feature of female worth’ (Latham, 1997, pg. 461). However, and contrary to their American counterparts who believed that only a few women are beautiful strictly speaking, the authors of our beauty guide argued that every woman can use her individual attractive traits in order to refine her image and empower herself (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 845). By the 1920s women who spent money, time and energy on their Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) adornment were not negatively judged; on the contrary, they were condemned if they did not do so. Even though all women were supposed to be entitled to coquetry, married ones were advised to be reasonably and prudently self-controlled. Physical Appearance and Health Caring for her looks would not make a woman appear frivolous in the modernist context since beauty was perceived as an indicator of fine health (Comiskey 2004, pg. 46-7) and vice versa; every woman who wished to stay beautiful, had to know how to remain healthy. The link between beauty and health is actually a cross-cultural view that still endures today. It is evident that future medicine will not only target the prevention and cure of illness but also the aesthetic design of the body. Modern philosophical accounts of medicine entertain health and beauty as ‘ideal physical states’ related to our definition of ‘good life’. Anton Leist, in a very recent evaluation of both beauty and health, came up with the view that these two comprehensive and complex phenomena are ultimately closely linked (Leist, 2003, pg. 187-8). Already in the inter-war period, beauty was inextricably related to the preservation of health and hygienic living conditions. In some instances, such as Nazi Germany, the body was the site in which political ideals were inscribed and the notion of a healthy body became political since it represented an ‘ideal microcosm for the healthy state’ (Gordon, 2002, pg. 165). Ugliness could be seen as a sickness because it was ‘detrimental to the individual… and because of its effects on the… spectators’ (Comiskey, 2004, pg. 45). According to the authors of the counsel book under discussion, there are three main factors that ‘all women ought to observe’ in order to maintain the ‘precious female beauty’. All three are linked to medicine and biology: health, cleanness and the scientific care of the body (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 6-7). Such viewpoints are the outcome of the contemporary medical advancements, which had just reached Greece at that time. The preservation of standard hygiene is upheld as a major concern not only for women, but for everyone in Greek society. The authors find the opportunity to condemn the Greek state as responsible for the neglect of hygiene conditions throughout the nation and to suggest the introduction of basic principles of hygiene as a compulsory course in elementary school curricula. Daily care subsequent to ‘the advices of medical doctors dealing with beautification’ is judged as indispensable. Keeping their bodies clean ‘to the very intimate details’ is recommended to all those women who wish to ‘attract true admirers and to gain psychological superiority and influence over others’ (ibid, pg. 7-8). Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) At the same time, western prescriptive literature and especially the ones written by men, equally attempted to impress upon (mostly) bourgeois women the importance of physical well-being and personal appearance. Pasteur’s theory on germs and scientific advances in medicine gave rise to discussions amongst physicians, editors and authors whose purpose was to convince women that it was their responsibility to remain healthy and consequently maintain their beauty (Hanna, 2003, pg. 329). Advice as to how to preserve a healthy household is also included since in inter-war Greece adequate ventilation and light in the bedroom as well as thorough sterilization of the tools used for personal hygiene (toothbrushes, combs or sponges) were still absent from the poor housing conditions for the majority of the population (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 51-7). Furthermore, fresh air, clean water and nutritious food were upheld as the bases of good health. In the same vein, the guide continues with reference to a series of recommendations regarding how women can remain healthy and beautiful. These recommendations conform to cultural stereotypes, long established and traditional standards as to what are perceived as female identities and roles. Thus, and throughout the content of the book, the authors report on every particular feature of female anatomy and style their study as the popularized account of medical findings. They give women specific advice and prescriptions on how to preserve and enhance the beauty of their body, always in accordance with the moralist viewpoints of the inter-war Greek (and not only) society. For instance, staying awake until late at night, smoking and playing cards constitute habits that women are advised to avoid if they want to remain beautiful, because they are deemed ‘unnatural’ for women (ibid, pg. 165-6). It is claimed that female beauty is more fragile and more prone to environmental changes and fatigue than the male one and that females should also avoid psychological stress and tensions since the latter harm human health and, consequently, beauty. So, women are advised to leave every trouble and problem outside their boudoir as good psychology aids the process of beautification (ibid, pg. 19-20). Linking Beautification to Social Roles and Employments Even though it is argued that women can beautify themselves at any time of the day, early morning is suggested as the most appropriate time, for it is quoted to have more impact on ‘sensitive organisms such as the female ones’ and because later on women will ‘have to undertake their family tasks’ and household cares. The undoubted primacy of marriage, childbearing and household chores as the culmination of their circumscribed lives is well in line with contemporary conditions in Greece, where undertaking family Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) responsibilities lead to women’s social acceptance. Caring for the family is considered the highest task for every woman and this opinion was shared not only by the specific (male) authors but also by female ones. A Greek female physician wrote in 1927: ‘according to new scientific findings, the most appropriate occupations for women are motherhood and household work... which are healthy and sacred occupations’ (Katsigra, 1927, pg. 147-8). So, women are advised to wake up early in the morning and devote the first … minutes of the new day to themselves. Those who wake up late ‘destroy both their beauty and their household’ (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 5960). Thorough cleaning and care of the face with specific prescriptions are considered indispensable to the process of female beautification, but it is also recommended that women from a very young age should learn to strictly discipline themselves and refrain from extreme manifestations of emotions. They should not allow their psychological state to appear on their face. Avoiding facial expressions is regarded as positive not only because it is a good way to avoid wrinkles but also because the external appearance of peace and calmness prevent others from guessing the woman’s inner thoughts or her viewpoints (ibid, pg. 77-8). The indirect advice given to women to hide their thoughts and opinions is compatible with women’s inferior social status and the lack of female autonomy. Within the contemporary context of economic, familial, sexual and social dependence, women ought to be of the same opinion as their ‘men’ and they lacked opportunities to freely develop their personalities and express their views. Early Greek feminists protested against this widespread social belief arguing that women are not the mere ‘shadow of their men’ and spokespersons of their husbands, contrary to the opposite belief that was deeply embedded in Greek society (Gaitanou-Gianniou, 1985, pg. 391). In addition to the socially conforming anti-wrinkle advice, the authors suggest that the tone of voice is an indication of the woman’s social upbringing as well as of her kindness. So, it is claimed that a woman is appreciated by a sweet voice and every woman should try to make her voice agreeable, warm and tender. Reading aloud poetry is one of the measures through which the female voice is supposed to become pleasing and melodious (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 125-6). The perfection of the breast (a central feature of female anatomy and identity) and its maintenance in good shape is thought to be the work of physical exercise, massaging and healthy cleaning. Cold showers and creams are also prescribed. Female shoulders are contrasted to the male ones. Strong shoulders are thought to be suitable for men, because they Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) give them grandeur, but they are viewed as unattractive for women who ought to have them round rather than square. Besides shoulders, the arms and forearms are examined; thin and round forearms are found to be ‘the prettiest for a woman while the muscular arms suit men better’. As the authors presume ‘female nature is compatible with thin and harmonious lines and this is why regular occupation with sporting activities is not good for women’ (ibid, pg. 131-4, 137). Only light exercise is proposed and the authors refer to medical reports from the USA that substantiate their claim that women’s regular sporting activity can harm not only their beauty but also their internal organs (ibid, pg. 137). In a similar note, even though during the same time period in the UK, female athleticism and physical culture could qualify as part of a contemporary women’s liberation project, the gender order did not change drastically and traditional gender roles remained in place (Zweiniger-Bargielowska, 2011). Such views are clearly the product of the cultural belief that women are ‘too frail to undertake the remunerative muscular labor of heavy industry’ (Hanna, 2003, pg. 332), a belief that in combination with the introduction of protective legislation for female workers in inter-war Greece limited the professional and economic opportunities for poor, working class women (Kyriakidou, 2002). Such views were combined with a wide array of deterministic theories, which stressed the prospect of ‘ensuring a husband, a home and children for every woman’ so that they will not have to work outside the household (Katsigra, 1927, pg. 147-8). The assistance of medicine and of contemporary medical achievements is deemed essential in order to save women from a general state of decay, attributed to a dysfunction of the nervous system (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 135-6). The female nervous system was reckoned to be more fragile than the male one and that is why hysteria and other allegedly nervous disorders were historically associated with women, as nineteenth century western societies tried to make sense of women’s changing roles in society after industrialization and urbanization (Briggs, 2000, pg. 246, Williams, 2002). Moreover, the authors argue in favour of the innovative inter-war hairstyle i.e. short hair for women, for both health and practical reasons, with the reservation that this new style may lead to increased hair loss for women and cite a number of medical studies linking baldness and short hair. Finally, dietary advice is given for a variety of different occasions (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 149-53, 169-71). The consumption of cosmetics is suggested but their moderate application is equally recommended since it is purported that their excessive use does not necessarily flatter female beauty (ibid, pg. 173-4). Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Feminine gestures, just like female emotions and opinions, should always be under strict discipline. The same is anticipated for the way in which a woman moves. It is mentioned that a beautiful woman should move in ‘a graceful and elegant way’ in contrast to men who, when walking, should ‘reveal their strength of character’ (ibid, pg. 15). Physical exercises are once more suggested in order to provide women with a fitting, ‘feminine’ walking style. The same restraints apply to the ‘feminine smile’, which is defined as ‘the sparkle that lights the fire of love’. Many women are cited to ‘own their success to their sweet and attractive smile’ and specific exercises every morning in front of the mirror are prescribed. Thus, women will be able to achieve the ‘perfect’, subtle smile. Such views are grounded on philosophical explanations of beauty based on human qualities and virtues, allegedly manifest through bodily moves. The way humans move, walk or gesticulate is supposed to reveal their lifestyle and abilities essential for a ‘decent life’. These include courage, moderation, generosity, justice and practical reason; a combination of moral and intellectual values (Leist, 2003, pg. 208). The beauty guide states that ‘women by nature lack the physical and psychological might of males and they cannot impose themselves. This is why God gave them the power to instigate respect by the way they walk, talk …, move and primarily by the way they dress’. If they neglect any of the aforementioned concerns, ‘it is their fault’ (Renos and Roussakis, 1928, pg. 185). At the end of the book, the issue of choosing appropriate cloths is addressed. It is argued that women who work with extravagant, short or generally provocative dresses do not inspire respect from their male colleagues who ‘cannot take them seriously’ while, in contrast, respect is paid to those women who are ‘properly’ dressed. Skirts in Europe rose to the knee in 1925 (Comiskey, 2004, pg. 37) and almost immediately became fashionable also in Greece. Short skirts became very controversial in Greece when in 1925, a dictator who assumed power through a military coup, sent his police force to actually measure the length of skirts and prohibit women from wearing short skirts in public (Moschou-Sakorrafou, 1990, pg. 226). The dictator lost power a year and a half later, but the moralist ideal of long skirts survived. The issue of working women’s dress code is associated with increasing concerns as to how women’s employment might influence their morality and decency. Inter-war perceptions mirrored the distinctions between male and female socially acceptable sexual behaviours. A woman’s ‘purity’ was highly valued, and it was presumed that her chastity would influence the public image of her whole family, especially that of her male relatives (father, brothers). In many cases, women who were not virgins before their marriages were Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) required to give additional dowry to their future husbands, ‘buying’ in that way their consent to marriage. In addition, the legal issue of ‘premarital adultery’ (a woman’s premarital sexual affairs) was amply discussed in Greek courts. Evidently, such discussions reveal that both in theory and in practice the taboo of virginity was undergoing a crisis (Vervenioti, 1994, pg. 45-6) during the interwar period. The conservative members of the middle classes in contemporary Western Europe expressed their anxiety over the challenge to hitherto welldefined gender roles: The working girl and the sexually loose woman became conflated into the same figure... Uncertainty about gender roles created anxiety, which in turn led to reaction... A new mother and wife role stressed domestic virtues based on heightened consumerism, a boon for expanding capitalist markets. Home economics claimed the status of a science and dignified the housewife as an expert (Bridenthal, 1977, pg. 493-4). Perceptions in Greece did not differ significantly. The majority of Greek men and women during the inter-war period remained adamant in their conviction that women’s natural setting was the household and that women expressed their psychological dependency on their male counterparts by considering marriage the solution to their social and financial concerns. The gap between the modernist promises for a better life and working women’s realities was clear. Most women responded by attempting to construct fulfilling private worlds. The female physician Anna Katsigra is probably the most characteristic example of the many individuals who shared the view of a socially dignified mother role for Greek women since they were thought to be responsible for the upbringing of a healthy future generation. She was convinced that: ...according to new scientific findings, the most appropriate occupations for women are motherhood and household work... which are healthy and sacred occupations... women should not work outside their homes if financial need does not arise. The unhealthy working conditions in the offices or in industry destroy women’s most valuable piece of their dowry, their health (Katsigra, 1927, pg. 147-8). Conclusion Female physiology in the ‘Counsel of Female Beauty’ is interpreted in the cultural framework of sexual dimorphism where men are superior and physically stronger. Beauty guides vested with the cloak of medical science were marketed to familiarize women with this cultural ideal and the assumed sexual hierarchy (Hanna, 2003, pg. 330). Throughout the book under study, it is directly suggested that with the aid of physical beauty and in Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) combination with good health, women in the patriarchal inter-war Greek society can be empowered, albeit within the, limited, widely accepted, traditional societal norms. Both health and beauty are valued. This value is often instrumental and it is associated with their ability to provide joy to others as well as to the beautiful individual itself. Good health is a resource for a high-quality life and physical beauty is valuable because it can provide the beautiful person with social recognition and wealth, an emblematic indication of an enjoyable existence (Leist, 2003, pg. 212-4). REFERENCES Brand, P. 1999. ‘Symposium: Beauty Matters’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 57(1) pg. 1-10. Brand, M. and Devereaux, M. 2003. ‘Introduction: Feminism and Aesthetics’, Hypatia Vol. 18(4) pg. ix-xx. Bridenthal, R. 1977. ‘Something old, something new: Women between the two World Wars’, in R. Bridenthal and C. Koonz (eds.), Becoming Visible: Women in European History, Boston. pg. 473-97. Briggs, L. 2000. ‘The race of hysteria: “overcivilization” and the “savage” woman in late nineteenth-century obstetrics and gynecology’, American Quarterly, Vol. 52(2) pg. 246-73. Cahill, A. J. 2003. ‘Feminist pleasure and feminine beautification’, Hypatia, Vol. 18(4) pg. 42-64. Comiskey, C. 2004. ‘Cosmetic surgery in Paris in 1926. The case of the amputated leg’, Journal of Women’s History Vol. 16(3) pg. 30-54. Gaitanou-Gianniou, A. 1985. Women and Politics [Gynaika kai Politiki], lecture given on April 1923, in E. Avdela and A. Psarra (eds.), Feminism in Inter-War Greece. An Anthology [O Feminismos stin Ellada tou Mesopolemou. Mia Anthologia], Athens Gordon, T. J. 2002. ‘Fascism and the Female Form: Performance Art in the Third Reich’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 11(1-2) pg. 164-200. Goodman, J. R., Morris, J. D. and Sutherland, J. C. 2008. ‘Is beauty a joy forever? Young women's emotional responses to varying types of beautiful advertising models’, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, Vol. 85(1) pg.147-68. Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Hanna, M. 2003. ‘For health and beauty: physical culture for Frenchwomen, 1880s-1930s’. Book review’, Journal of the History of Sexuality 12(2) pg. 329-33. Jelin, E. 1990. ‘Citizenship and identity: final reflections’, in Elizabeth Jelin (ed.), Women and Social Change in Latin America, London and New Jersey: 184-207. Katsigra, A. 1927. ‘The girl’s work’ [I ergasia tou koritsiou], Ellinis, 7/6-7, pp. 147-8. Kyriakidou, M. 2002. ‘Labour law and women workers: a case study of protective legislation in inter-war Greece’, European History Quarterly Vol. 32(4) pg. 489-513. Latham, A. J. 1997. ‛The Right to Bare: Containing and Encoding American Women in Popular Entertainments of the 1920s’, Theatre Journal Vol. 49(4) pg. 455-73. Leist, A. 2003. ‘What makes bodies beautiful’, Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, Vol. 28(2) pg. 187-219. Marshall, B. L. 1994. Engendering Modernity: Feminism, Social Theory and Social Change, Cambridge. Mavrogordatos, G. T. 1988. ‘Venizelism and bourgeois modernisation’ [Venizelismos kai astikos eksychronismos], in G. T. Mavrogordatos and C. Chadjiiosif (eds.), Venizelism and bourgeois modernization [Venizelismos kai astikos eksychronismos], Herakleio, Greece. Moschou-Sakorrafou, S. 1990. A History of the Greek Feminist Movement [Istoria tou Ellinikou Feministikou Kinimatos], Athens. Radcliffe S. A. 1993. ‘“People have to rise up-like the great women fighters”: The state and peasant women in Peru’, in S. A Radcliffe and S. Westwood (eds.), ‘Viva’: Women and Popular Protest in Latin America, London and New York: 197-218. Renos, M. and Roussakis, G. N. 1928, The Counsel of Female Beauty [O Symvoulos tis Gynaikeias Kallonis], Athens. Singh, D. and Singh, D. 2011. ‘Shape and Significance of Feminine Beauty: An Evolutionary Perspective’, Sex Roles, Vol. 64(9-10), pg. 723-31. Women in Society Volume 3, Spring 2012 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Veremis, T. 1989. ‘Introduction’ [Eisagogi], in T. Veremis and G. Goulimi (eds.), Εleftherios Venizelos. Society-Economy-Politics During his Era, [Eleftherios Venizelos. Koinonia-Oikonomia-Politiki stin Epochi tou], Athens. Vervenioti, T. 1994. Women in the Resistance. Women’s entrance in political scene [I gynaika stin Antistasi. I eisodos ton gynaikon stin politiki], Athens. Williams, E. A. 2002, ‘Hysteria and the court physician in Enlightenment France’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 35/2, pp. 247-55. Younger, B. 2003. ‘Pleasure, Pain, and the Power of Being Thin: Female Sexuality in Young Adult Literature’, NWSA Journal, Vol. 15(2), pg. 45-56. Zweiniger-Bargielowska, I. 2011. ‘The Making of a Modern Female Body: beauty, health and fitness in interwar Britain’, Women's History Review, 20(2), pg. 299-317.