Literacy Narrative-Smith - Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives

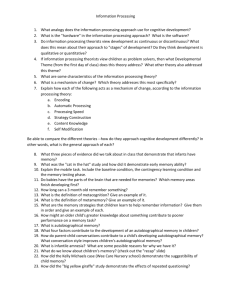

advertisement

The Musings of an Undeterred Voice An Introduction Reflection has always been a tricky task for me. Yes, I can recall those times as a little girl where I tumbled down the rabbit hole through a portal of words every time I opened a book—every new scene and set becoming a ripe wonderland to explore. I can also remember, much like Alice, being dissatisfied with the real world around me, wishing desperately to be swept up into a place of magic and mystery. In fact, this onslaught of vivid daydreams eventually led me to adopt the life of a writer, where I could fully emerge into foreign plots in more fulfilling ways—the unconscious dreamer now becoming lucid in the stroke of a pen. However, these memories, though I remain fond of them, are so divorced from my present experience of life as a reader and writer that the relevance is now lost to me. What need have I to reflect on something that no longer directs my hand? Yes, everything has its foundation, everyone has a seed that was dropped unto the earth at one point—but I am no longer that seed. As I write this “reflection,” my intention is not to focus on the memories of my childhood, or a past that I can no longer relate to. Rather, my intention is to reflect on subjects that influence me now, that direct my hand now. In order to do this, I realize that I must write whatever it is I want to write. If I am going to reflect on what inspires me as a writer and reader, I need to reflect on what’s inspiring me right now. What subjects are at the forefront of my mind? What are the little things in life that compel me to think and meditate? What humbles me? Where do I struggle? These are the questions that matter, that are worth reflecting on. Mumblings from my mind are strewn out unto paper and it becomes clear that everything inspiring me can be found in these words. While there are many habits that I hope to gain as a writer through this process, conversely, there are many habits I am trying to break, and one of them is imposing my will upon the process. I want the process to be innovative and exciting, and for the product to be something that carries my voice and character—and permitting myself the space and time to free-write is the best way to achieve this. Giving up on the ambition to control the subject, I will instead engage with the subject. Thus, through the following snippets and musings, I will form a collage of thought 1 experiments where I can first meditate on a particular subject and then finally allow the subject to direct my hand. A Map “The Musings of an Undeterred Voice” is a compilation of 6 narrative pieces that form one cohesive essay. Each piece contributes to the collage of thoughts or subjects which inform my present experience as a writer. This section will serve as a reader’s map, to help guide those willing to engage. “Sensations and Memory”: This speculative piece invokes readers to cast their attention toward memory and to think more critically about the internal-external experience. Pause at questions asked, sit and speculate, wander and wonder—be engaged with the process. “Snapshots and Stories”: This piece is a response to another literacy narrative by Johanna Lin Want, “13 Ways Words Wrote Me.” Want’s narrative inspired me at the start of this project for its use of poetic snapshots to capture a particular mood or experience many writers and readers may share. While it was reflective and personal to herself, it also remained open and inclusive, sparking nostalgia in all readers. Stories, both personal and universal, unwind from snapshots—and I hope that, through this piece, I can bring thoughtful attention to this subject. “Forms and Structures”: This poem is a contemplative reflection on the rigidity, flexibility, and ephemerality of form and structure in both the literary world and the world at large. “Intimacy and Flow”: This piece is a response to a literacy narrative by Carolyn Romano, “The Anatomy of a Poet,” which was the result of a process that was much like the one I adopted for my own project—one of pure engagement with the subject. Like any other work of art, one of the most important parts of the finished work is the process leading up to it. While the end result is what will be remembered and revered, it is only a reflection of the magic that transpired before the dawn of its day. Together, both a mind, pregnant with the zeal of inspiration, and a steady hand, 2 combining mere oils, dyes and strokes, give birth to Beauty. And for Beauty to emerge from the womb, that sacred ritual of intimacy and flow must precede it. “Our Muse, Philo Sophia”: This piece is not only a response to a literacy narrative by Jacob Anderson, but it is an ode to a subject deserving of my honor and respect: Philosophy. To which I owe many of my present achievements as a writer. “The Toiling Wordsmith”: This piece is intended to be read as a troubled journal entry from a wordsmith and depicts the story of my own struggle as a writer. As a writer I habitually find myself caught on the fence that divides rhyme and reason. On one hand, I am an aspiring poet, whose dream is to make an art out of written material. On the other hand, I am an aspiring philosopher, whose passion for system building and close logical analysis often conflicts with my initial dream. To my dismay, it is difficult for me to find neutral ground between the two camps. At present, reason and logic come more naturally to my own mind, and can be beckoned with mere strength of will, while creative work pays no mind to the will and comes only when I have been inspired. What I hope to do with this piece is express this tension between two states of mind, and the yearning for the elusive muse which ushers in the blossoms of creativity. I also hope to demonstrate how the writer’s insecurities can become obstacles or delusions that prevent her/him both from lifting the pen with due confidence, as well as recognizing one’s own talent for the trade. 3 Sensations and Memory I from time to time wonder about the timeless dependency and fascination all life seems to have with the senses. The human being is a walking compendium for the phenomena of life—yet, what number of us can provide an adequate response for why we are so fascinated and dependent upon sensations? Our five sensory faculties act as a medium between us and that; the internal I and the external world—so might it actually be the external world that entices our fascination after all? And at what point did our fascination with the external world originate? This desire to connect to the external world, to immerse oneself in the external world, to be known to the external world; has it always been this way? Can life be lived internally? Or does this connection and immersion into the world around us provide some kind of reassurance that, indeed, we are alive? At once, I recall the young Nepalese yogi, Dharma Sangha, informally known as “the Buddha Boy.” Dharma Sangha, for ten months, renounced the use of his senses and his interaction with the external world, and reportedly partook of no food or water, nor did he leave his seat in the hollow of a tree in order to relieve himself, driven as he was to enter into a deep meditative state. In 2006, The Discovery Channel produced the documentary Boy with Divine Power, which filmed Dharma Sangha continuously for 96 hours only to confirm that the boy had persisted in his meditation without need for food or drink, showing no symptoms of dehydration. What was that, in his mind, which inspired and enabled him to transcend his dependency on the senses? Or did he ever truly transcend his dependency on the senses? What occurred in that deep state of meditation? Did all of his ideas and concepts that require the recollection of sensations (sights, smells, tastes, sounds and touch) fall away? Any representation of memories and images, within the human understanding, are dependent upon the collective sensations of a lifetime—but did he reach a place there in his mind where none of these things were a necessary component of experience? Or do sensations never cease to form our experience? Perhaps it may be true that, even in the mind, we may not be able to escape that which we’ve inherited from the world: memories of sensations. Or might there be a higher mind within that transcends the necessity of sensation and memory? Dharma Sangha never revealed the answers to these questions, so I am left in a state of speculative unrest. 4 And what is memory? The more I reflect on what may appear to be something so obvious, the more I wonder at its obscurity: what is this perplexing phenomenon? Could memories really be composed of nothing more than a collection of sensations that were once observed through our sensory organs and, after being reflected upon through the operations of the mind, had thence given shape to concepts and ideas that would inform our perceptions and field of experience? Yet, memory, like time, is so fleeting, surfacing only when practical: “The cerebral mechanism is arranged just so as to drive back into the unconscious almost the whole of [one’s] past, and to admit beyond the threshold only that which can cast light on the present situation or further the action now being prepared—in short only that which can give useful work. At the most, a few superfluous recollections may succeed in smuggling themselves through the half-open door. These memories, messengers from the unconscious, remind us of what we are dragging behind us unawares” –Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution But, as fleeting as memory is, much depends on it. I challenge you to think of the existence of one thing whose progression is not, to some degree, dependent on memory. Everything in human society is built upon memory: The existence of the DNA strand (ancestral hand-me-downs) The evolutionary progression of earth and its inhabitants (remnants from the past reveal where we have come from) The sciences The evolution of technology Human knowledge The list can only grow! One might venture to argue that God’s existence (should God exist) would not be dependent on memory—but remember again that I said the progression of a thing is dependent on memory, and if God (a supremely perfect being) should exist, he would not need to progress, else he would cease to be a supremely perfect being! Literature, too, is dependent upon memory; and my growth as a literate individual is wholly dependent upon five things: my continued existence, my passion, those who support me, my experiences and my memory—and not only those memories having to do with literacy. In fact, for myself, some of my richest bodies of written work were not inspired by any particular experience I had with 5 reading or writing, but by accumulative life experiences—the writer’s words to be seasoned like a fine wine, well-aged. Even the new worlds I intend to construct with the tools of pen and paper depend upon the myriad of memories and experiences I’ve encountered in life. Each scene in a story, a mosaic of memory relayed through sensations, symbols and words—the words that I happen to extract from memory, splattered about my artist’s palette. The pen, my paintbrush; the mind, my canvas. Snapshots and Stories Snapshots, allusive images, shifting stories, and shadowy scenes that slip through the cracks of memory— our bittersweet possessions, or so it seems. In “13 Ways Words Wrote Me,”1 the snapshot is central to Joanna Lin Want’s narrative, and is what strengthens her artistry. But what makes the simplicity of a well composed snapshot so striking? And what makes stepping into a snapshot of someone else’s memories so compelling? There is a certain enthrallment we all share with being drawn into a story, and a snapshot is a story in want of completion while a writer is all too willing to fill in those gaps. I notice that as I read each stanza of Want’s poem, I am drawn into the snippets of a life that feel familiar. It is as though she holds a fishing rod and casts its line into the collective unconscious, our lake of shared experiences. And what had previously appeared to me as some shallow figure swimming beneath the surface now comes forth, shuttering and thrashing in midair as a bustling creature bearing new life. Was this truly the same dull fish I’d seen before? I am enticed and inspired by her snapshots, and she herself is enticed and inspired by the stories of others. Upon visiting the world of Princess and the Pea, she became sympathetic to the Princess’ plight. Upon reading Dead Until Dark, Snapshot “The injustice of going to bed Is lessened By the stories my father tells Tonight I choose Princess and the Pea I imagine stacks and stacks and stacks of mattresses Sure that I too would not have slept well at all Because of that tiny pea” Joanna Lin Want, 13 Ways Words Wrote Me she befriended characters whose personal stories and 1 Posted in the Digital Archives of Literacy Narratives in 2011 6 lives are thought to be no more than fictional. But do stories need to be real to be relevant? Have we not all been there before in some shape or form? The stories never change—only the lens that captures Snapshot “I read Dead Until Dark By the pool in a red bathing suit Sookie and I are on a first name basis All summer my days are filled with trying to learn To write like a scholar But at night I am a poet And a girl in need of a story, and friend” it. And through snapshots, we relive what we’ve forgotten and lost… Snapshots are forever cherished by those who revel in the preservation of memory, and yet, paradoxically, the snapshot can be a result of the incompetence of memory. Elusory images are the remains of incomplete recollections after all. We are deceived by our minds, accepting faulty memories as complete, but memory fails Snapshot “There are no words At fourteen For the surprise of throwing a handful of earth Into the earth for a friend The rabbi says prayers in a language I can’t understand— The only words that make any sense that day” Joanna Lin Want, 13 Ways Words Wrote Me to capture that which lies beyond the veil of perception. But still we hold on, because it is the snapshot of a long-lost moment that speaks with the most conviction to us. What else do we have to remember the moment by? Nevertheless, I sometimes fear that nostalgia only leads us to dead ends— moments that are forever buried, and perhaps should stay buried. A snapshot found within the mind is not merely a visual recollection; it is no longer the eyes that convey that once-lived experience—but a memory, embraced by the arms of dissolution—its carcass, a buried nothing. And here we sit, nostalgic at its tombstone. As though visiting a grave may open the bridge between us and the forgotten. But the bridge is just as imaginary as our memories of that body, which has already gone. This body, this tombstone—are these things really all we have left of something we’ll never again behold? The hermit has long moved on from its shell… Yet, stubbornly, we hold on, attached to our delusion. Moment after moment after moment stacks up in the graveyard of memories that precede us—and out of our instinct toward the preservation of life, we hiss at the approach of every end. Hence, our attachment to snapshots—a feeble triumph over the end of an experience. “Time may have hung a 7 rope around the neck of my experience, but HA! You see, I still have its corpse in my hands, to hold and to remember!” But time snickers patiently, because soon even your body will be snatched by time. And who will you become afterward? A memory, diluted and dispersed into flimsy fragments. You really live on through a snapshot, do you? But then again, who is the ‘you’ that lives now? The ‘you’ that will one day vanish from the world even if the memory of ‘you’ is preserved? Isn’t it strange that we can remain so attached to memories, snapshots, and stories of the past, which only seem to be subtle reminders of the inevitable end to everything? One day, a memory and a story is all we will be. Perhaps, that’s what makes them so revered. It may be the only way we can live on. But might it be the case that we view the world only through snapshots? Sometimes I fear that the world is intangible. That no matter how deep the desire to touch and feel and taste this material existence burrows, we will always rummage frantically, pulling back with mere snapshots and empty hands. Every sensation, every perception—isn’t all of it is just filtered through the mind, which can only receive an endless feed of perforated information? You know “the wind” only so long as you have sensory neurons to tell you you’ve have felt it. You see “the wind” only so long as you have eyes to tell you you’ve seen it. You smell “the wind” only so long as you have a nose that tells you you’ve have smelt it. But have you ever really known “the wind” apart from your limited perceptions? Or have you only known your own idea, a snapshot, of a sight or smell or feeling? What lies out there, beyond the veil of perception? Nothing truly exists to us apart from the snapshots which the senses deliver to the stoop of our minds in the form of ideas. And from these Snapshot “People by Peter Spier A book so big it seems to cover most of the bed Across two pages dull pink buildings and pale greens buses Every person in grey coats— ‘But imagine how dreadfully dull this world of ours would be if everybody would look, think, eat, dress, and act the same!’” Joanna Lin Want, 13 Ways Words Wrote Me ideas, language spins a tale, naming these collective sensations: Wind. But all we know are our partial ideas and perceptions—subjective snapshots. We can never truly know the wind, nor can we know the world. But what would the wind and the world be without its perceivers? 8 These pixelated segments, while beautiful, depend on the imagination to fill in blurred gaps. Our experience has its limitations, just as the mind has its limitations. And just as there is no one mind that is akin to another’s, there is no one experience of the world that is akin to another’s. Could this be one more reason why we are fascinated by the snapshots presented to us by another mind? In a sense, this may be the only way we can expand our own limits, and our perception of the world. Forms and Structures In my mind, there is always a blueprint too nebulous to take on the rigidity of form. Yet, these hands, with an ache to create, find their muse. We, who build bridges to concepts that inspire our construction of scenes, chisel at our own blocks of obstinate stones to clear space for endearing detail (sculpting beauty, as we see it) and then comes, inevitably, the u n r a v e ling of abstractions. Isn’t it wondrous? To reach hands into wet sand, 9 forming castles out of pebbles? To reach hands into burgeoning language, forming poems and tales out of snatches of words? There is an Art To the Transmigration of Ideas. An idea finds its path in Cirque De La Vie (the circus of life) through a body of symbols embellished with ephemeral meanings as pronounced by those shifting tongues of Zeitgeists; Words and Symbols? A veneer that decorates underlying substance; to wax and wane as cycling dew; But dew that graces morning grass never waits to greet the noonday’s sun, and the sun that spots the grass at noon sees not grass lit by evening moon. Our Literary History— A body of water, Reflective, yet transparent. Forever shifting and contouring in tandem with future beholders. 10 Intimacy and Flow Wait. Receive. Penetrate. Drag out. Let Flow. This is how the writing process goes. It is not a roundabout process, but a process that seeps into the subject and is enlivened by it. To gaze at form and memory at a distance, to poke its sides but never penetrate? Never engage? I am not merely an observer. I must observe, and I must engage. Passivity and activity; Yin, but then Yang. Let the transience of form, meaning, and memory stand as the reason for engaging in greater intimacy with them. Is transience not, in part, what makes winter snowfall and spring cherry blossoms so cherished and desirable? As we watch the coming wilt of early bloom, a subtle sadness looms as Beauty withers. We hold our breath as though it holds the moment, as though trapping air in those caged twin sacks might halt time’s passing. And within, there burns a deep longing to be immersed in the Beauty of the moment before her last petal is plucked up by the wind. In our hearts, we just want to see the endurance of something that is both ephemeral and beautiful. But these beautiful bodies cannot live on as they are, so intimacy is the sought-after resolve. You see, form, while rigid, is best felt when it is not. Life is something that dances and moves. Thus, if we want the subject to come to life, we have to let it dance and move! Carolyn Romano speaks of the anatomy of a poet. How her hand twists and loops and shakes. How her traveling footsteps press love letters into dirt. And even how her words are ignited by the life that breathes them out: My young heart wants dancing things wants running things wants singing things and winging things and waiting things and bringing things and is tired of all these sitting things. Words are all about music and motion Carolyn Romano, “The Anatomy of a Poet” If our task is to drag out these ideas, we must let them flow. We must engage with them to the point where we become them, where it becomes us. Then, let it bring to light those parts of ourselves that we try to hide. 11 One night I realized: My shame is merely mislaid blame. So I turned up the music in my living room and I let go. I let my hips snake little circles and then sway, sashay, even shimmy. Suddenly I could breathe. Later I felt good. I felt sexy, sweaty and unashamed. And this, I realized, is how I want to feel after writing. I want to feel as though I have given myself permission to love all the shapes I inhabit. Carolyn Romano Wait. Receive. Penetrate. Drag out. Let Flow. But then recognize that through the process of becoming intimate with the ideas within and with the forms without, we cannot help but to also become intimate with ourselves. “When I was considering how to write a personal literacy narrative, I approached literacy more as intimacy than as a skillset. And yet, even when I thought of my various skills in literacy, I moved to poetry and from there to intimacy and what, may I ask, is more intimate than the stories that we carry within our bodies? Somehow, particularly in recent years, inspiration, artistry, and exquisite experience always come back to a physical reality in order to transcend it. This is why I chose to write the poems that were waiting in my muscle and bone.” Carolyn Romano 12 Our Muse, Philo Sophia Resistance to the tide Bears fruit in time— Where oceans plunge deep, Islands soon arise, Each to stand firm, And expand “I had no mirror for my values. They were mine alone, and I felt isolated. But I wasn’t going to compromise my values just for social convenience… One must cultivate the values important to them, and climb mountains to be away from the rubble when fury swells in the bosom like a tidal wave.” Jacob Anderson, “Becoming SelfLiterate” upon the grounds of its own foundation. Progress and evolution, Growth and the flowering of knowledge— To unwind as the echo Of questions asked. And blessed is the one Who dares to ask. Jacob’s penmanship— an ode to Philo Sophia. “I was the one who dredged the darkest marshes of my interior and became terrified at the question marks I saw reflecting from every mirror in my mental hallways. I was questioning everything—it was an instinct. I was questioning the validity of my existence and that of those in the world around me.” Jacob Anderson Our spirits, saluting the wisdom of “grand eagles,” our “catalysts for becoming” as he called them. Another life’s narrative cultivated through words passed down, a blessing of our wise muse, Philo Sophia. “Nietzsche changed all of this for me. Reading him only strengthened my resolve. As I read Nietzsche, my indignations toward religion, politics, and societal institutions in general, were validated. Years of anger swelled up and sucked out with the tide of a movement of energy. I found my companion. Now I had a mirror. Now, I wasn’t so alone… Since Nietzsche, I became a full-blown philosophy addict.” Jacob Anderson 13 The Toiling Wordsmith Wayfaring beneath a sun that uplifts The Age of Reason, my mouth, too often, is parched of words that might quench a musical soul. The soul that once marveled at the experience of life has withered in this waste land. The coming of age has brought the weathering of joy. Long nights with a pen in hand, but no ink, led me to realize I am drained of what once inspired me in my youth. I know not what a poet is. Yet it is what I have yearned to be. Be that as it may, I stand as my own obstacle. Instead, I have become a perfectionist who looks upon beauty and requires its presence as a means to meet the strict criteria I impose upon myself—sensing within me some imbalance to be set right. Grace is no longer a saint that twines my words—grace is forced. Manhandled and dragged out to be analyzed under microscopes and monocles. I am not on my knees before Saint Grace; grace hides in the wake of my own shadow, as I stand before it brandishing a whip. I do not ask it to be my guide, I will it to do my bidding. And then at night, I tear hairs from my scalp, possessed by this ego whose sardonic whispers beset and ensnare my core with illusory notions: You’re not good enough. Yet, illusory as they are, I am too often convinced by them. Poets spin tales into metaphors and rhythmic verses. Deforming substance and topping it with frilly hats. Some say the secret is not skill, but a passive will. Their wish is not to be good enough, but to be as a boat on the rivers of passion. Upon sitting and listening to unconscious warbling, they are made a vessel by which, as a friend once said, poetry becomes actualized. But then reason persuades me to inquire unto the nature of the unconscious. What faculty have we to receive unconscious warbles? And whence do they come? What is the unconscious, and what has it to do with me? And how does one become a vessel for a thing that has not its own will? Or are we to say that the unconscious has a will—a spirit even? One with limited understanding can only speculate. And endless speculation oftentimes will provoke our descent into madness. Force contends with flow—and I am stuck in the ways of force. Has this patriarchal Zeitgeist, which advocates the use of force, finally imprisoned me in its web of fate? Can I break down years of cultural 14 conditioning? It’s quite the paradox. If I become one with the ocean that advocates force, I become yet another wave being moved by the current—with no force of my own. In this Age of Reason, I fear that I am cut off from spirit and can no longer hear its whispers. When sweet life says, “I bid you adieu,” will I finally merge with that spirit that dictates the hands of poets? But then, to what end? Should there be an end? What end might there be when you are at the end? Shay Smith Works Cited Anderson, Jacob. “What It Means to Become Self-Literate.” Berea College, 2015. Print. Ayer, A.J. and Jane O’Grady, ed. A Dictionary of Philosophical Quotations. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992. Print. Romano, Carolyn. “The Anatomy of a Poet.” Berea College, 2015. Print. Want, Joanna Lin. “13 Ways Words Wrote Me”. Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives, 2011. Web. < http://daln.osu.edu/handle/2374.DALN/2050>. 15